Catholicism and the Civil Rights Movement

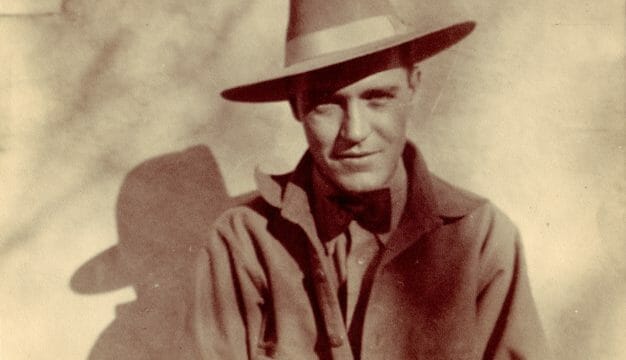

Priests in Voting Rights March

In Alabama the Catholic Church’s involvement with the civil rights movement was decidedly mixed. Most of Alabama‘s white Catholics shared white southerners’ racism and initially opposed the goals of the movement. They preferred order and stability instead of activism for integration and racial justice. Catholic teaching clearly opposed racial discrimination, however, and after the mid-1960s there was little official sympathy for segregation. For most of the civil rights movement, the Catholic Church in Alabama remained on the margins of the debates over integration and focused on internal Church affairs. It took the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights to draw the Church from the margins into the mainstream of the movement.

Priests in Voting Rights March

In Alabama the Catholic Church’s involvement with the civil rights movement was decidedly mixed. Most of Alabama‘s white Catholics shared white southerners’ racism and initially opposed the goals of the movement. They preferred order and stability instead of activism for integration and racial justice. Catholic teaching clearly opposed racial discrimination, however, and after the mid-1960s there was little official sympathy for segregation. For most of the civil rights movement, the Catholic Church in Alabama remained on the margins of the debates over integration and focused on internal Church affairs. It took the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights to draw the Church from the margins into the mainstream of the movement.

After the Civil War, the Alabama Catholic Church abided by the demands of state-sanctioned segregation, even as it sought to meet the spiritual needs of the state’s African American Catholics. As a result, the Church built separate parishes, schools, and hospitals and invited members of religious orders (most notably the Society of Saint Edmund and the Society of Saint Joseph) to work exclusively with African Americans. This practice reinforced segregation, but it also provided spiritual care and nurtured a separate community identity among African Americans. The resulting black Catholic subculture would become one foundation for later civil rights activism, especially in Mobile and Selma.

Not Entirely Segregated

State laws and local ordinances may have demanded separate facilities, but Catholic Church–related activities were not strictly segregated. Blacks and whites occasionally participated in religious functions together. They attended the same parish at times, even if African Americans often sat apart from whites and received communion after white parishioners. Similarly, the diocese-wide Christ the King celebration (an annual parade and open-air mass held in Mobile’s Bienville Square and smaller venues in Birmingham and Montgomery) included representatives of black parishes and lay organizations. Diocesan-wide organizations were also open to both white and black laypeople.

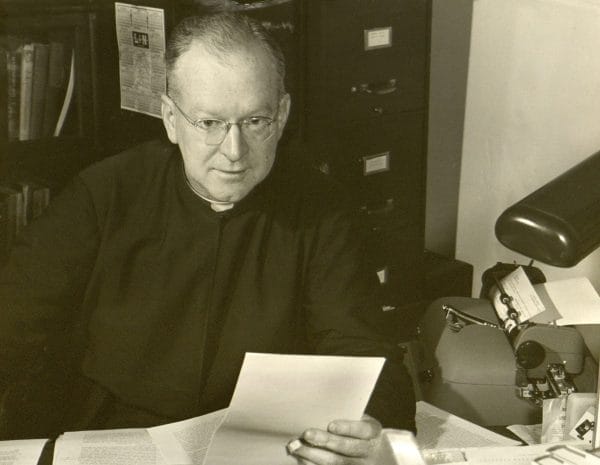

Father Albert Foley

Despite these internal arrangements, Archbishop Thomas J. Toolen forbade priests to challenge publicly the state’s segregation laws or participate in demonstrations. They were instructed to work within the law and not force confrontations that would agitate the state’s white population. This curtailed the activism of a few priests and invited conflict between Toolen and those Catholics who feared that the Church was in danger of losing its moral authority on race. For example, in the early 1960s, Father Albert Foley, Jesuit professor of sociology at Spring Hill College, worked with Mobile Mayor Joseph Langan (himself a Catholic) to broker an agreement that would desegregate Mobile’s downtown businesses. Langan eased Toolen’s mind about Foley’s involvement, but on more than one other occasion Toolen tried to have Foley re-assigned out of the diocese. And in Selma, African American Catholics took encouragement from the white priests of the Edmundite order, who treated them with fairness and dignity and assured them of their spiritual worth. These priests, by their refusal to condemn civil rights activism, encouraged African Americans to press for change. The activities of these few Catholics signaled the direction that the Church would take as the civil rights movement intensified.

Father Albert Foley

Despite these internal arrangements, Archbishop Thomas J. Toolen forbade priests to challenge publicly the state’s segregation laws or participate in demonstrations. They were instructed to work within the law and not force confrontations that would agitate the state’s white population. This curtailed the activism of a few priests and invited conflict between Toolen and those Catholics who feared that the Church was in danger of losing its moral authority on race. For example, in the early 1960s, Father Albert Foley, Jesuit professor of sociology at Spring Hill College, worked with Mobile Mayor Joseph Langan (himself a Catholic) to broker an agreement that would desegregate Mobile’s downtown businesses. Langan eased Toolen’s mind about Foley’s involvement, but on more than one other occasion Toolen tried to have Foley re-assigned out of the diocese. And in Selma, African American Catholics took encouragement from the white priests of the Edmundite order, who treated them with fairness and dignity and assured them of their spiritual worth. These priests, by their refusal to condemn civil rights activism, encouraged African Americans to press for change. The activities of these few Catholics signaled the direction that the Church would take as the civil rights movement intensified.

Seeking Gradual Change

Martin Luther King Jr. and Sisters of St. Joseph

In 1958 the American Catholic bishops issued a statement condemning segregation and calling for racial justice. They declared segregation a moral wrong that was not to be tolerated. The bishops’ statement declared that “the heart of the race question is moral and religious” and that “segregation cannot be reconciled with the Christian view of our fellow man.” Privately, Archbishop Toolen concurred in that opinion, but he still insisted that change take place gradually. He denounced the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, in which four young African American girls were killed. That same year, he permitted auxiliary bishop Joseph Durick to join with 10 other Birmingham-area Protestant and Jewish clergymen in a statement that acknowledged some hostility toward court-ordered school desegregation but counseled that their followers should avoid conflict and go along with the decision. Both moderate and liberal clergymen urged respect for law and order and reminded Alabamians that every human being is “created in the image of God and is entitled to respect as a fellow human being with all basic rights, privileges and responsibilities which belong to humanity.” Later that year, Durick signed a similar appeal to the city’s African American inhabitants, urging them to forego demonstrations in favor of a “peaceful Birmingham.” As a response to that second statement, Martin Luther King Jr. composed his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Martin Luther King Jr. and Sisters of St. Joseph

In 1958 the American Catholic bishops issued a statement condemning segregation and calling for racial justice. They declared segregation a moral wrong that was not to be tolerated. The bishops’ statement declared that “the heart of the race question is moral and religious” and that “segregation cannot be reconciled with the Christian view of our fellow man.” Privately, Archbishop Toolen concurred in that opinion, but he still insisted that change take place gradually. He denounced the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, in which four young African American girls were killed. That same year, he permitted auxiliary bishop Joseph Durick to join with 10 other Birmingham-area Protestant and Jewish clergymen in a statement that acknowledged some hostility toward court-ordered school desegregation but counseled that their followers should avoid conflict and go along with the decision. Both moderate and liberal clergymen urged respect for law and order and reminded Alabamians that every human being is “created in the image of God and is entitled to respect as a fellow human being with all basic rights, privileges and responsibilities which belong to humanity.” Later that year, Durick signed a similar appeal to the city’s African American inhabitants, urging them to forego demonstrations in favor of a “peaceful Birmingham.” As a response to that second statement, Martin Luther King Jr. composed his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Within the Diocese of Mobile, the civil rights movement complicated relationships between white and black Catholics. In 1963 an African American Mobile man tried to attend mass at a white parish in Orrville. Members of the parish refused him entry, forcing him to drive 15 miles to the nearest African American parish in Selma. Prior to the civil rights era, he might have been allowed to attend the Orrville service, but by 1963 race relations were too volatile for white Alabamians to deviate from the community’s racial status quo. The man complained to the archbishop, who threatened to close the small church if parishioners ever again denied a fellow Catholic—white or black—the right to attend mass. White parishioners, stunned at the archbishop’s reaction, agreed to comply.

Segregation in Schools

Bishop Thomas J. Toolen

For more than a decade, southern school systems resisted implementing the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Parochial schools were almost as segregated as public schools, and by the 1960s African American parents found this arrangement increasingly unacceptable. In 1964, after pressure from African Americans and sympathetic whites, Toolen announced the desegregation of diocesan schools beginning in September. That announcement provoked angry white dissent, and many parents threatened to withdraw their children from parochial schools. In deference to white sentiment, admission to schools took place on an individual, case-by-case basis, which meant that actual integration occurred only gradually.

Bishop Thomas J. Toolen

For more than a decade, southern school systems resisted implementing the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Parochial schools were almost as segregated as public schools, and by the 1960s African American parents found this arrangement increasingly unacceptable. In 1964, after pressure from African Americans and sympathetic whites, Toolen announced the desegregation of diocesan schools beginning in September. That announcement provoked angry white dissent, and many parents threatened to withdraw their children from parochial schools. In deference to white sentiment, admission to schools took place on an individual, case-by-case basis, which meant that actual integration occurred only gradually.

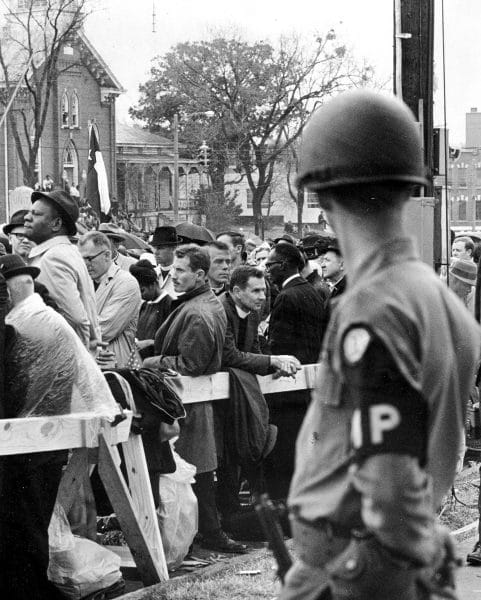

The march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965 galvanized public sentiment over civil rights and the role of the Church in the South in racial justice issues. Unlike previous demonstrations, this one included a large number of clergy, who had come from all over the country at the invitation of Martin Luther King Jr. Some 35 or 40 Catholic priests and an unknown number of nuns came to Selma, against Toolen’s wishes, to support the voting rights march. Black parishioners at St. Elizabeth’s, the Edmundite parish in Selma, even housed visiting marchers, white and black. Montgomery’s City of St. Jude, a social services organization founded in 1937, provided camp sites and support to the marchers, and its hospital attempted to save Viola Liuzzo after she was shot by members of the Ku Klux Klan. In off-the-cuff public remarks, Toolen conceded the need for change in race relations, but he denounced the marchers as “crusaders” and outsiders who knew little about life in the South. Toolen also criticized priests and especially nuns who participated, believing that they had no place in such an environment. Toolen did not seek attention for his opinions, but many white observers viewed his words as support for segregation. Protestants and Catholics alike held him up (somewhat unfairly) as a spokesman for the segregationist cause.

Voting Rights March

Despite Toolen’s objections, the voting-rights march took place with many priests and nuns in attendance. Not long afterward, the U.S. Congress passed and Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In addition, the Selma demonstrations caused many Catholic priests, nuns, and laypeople to increase their efforts on behalf of racial justice. In 1968, for example, Mobile’s Most Pure Heart of Mary parish became the base of black power protests in that city. Also that year, Toolen relaxed a diocesan rule that forbade priests and nuns to participate in civil rights demonstrations, a concession to the reality of the times. The Catholic Church in Alabama was far quicker than other white southern denominations to make the goals of the mainstream civil rights movement official policy. Indeed, in 1970 Toolen’s successor, John L. May, claimed that the Diocese of Mobile’s record in race relations surpassed that of his native Chicago and saw great promise in the progress made in the diocese. Many people may have quarreled with May’s optimistic assessment, but there is no doubt that by the early 1970s the Catholic Church refused to condone discrimination.

Further Reading

- Moore, Andrew S. The South’s Tolerable Alien: Roman Catholics in Alabama and Georgia, 1945-1970. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.