Black Militias in Alabama

Capital City Guards

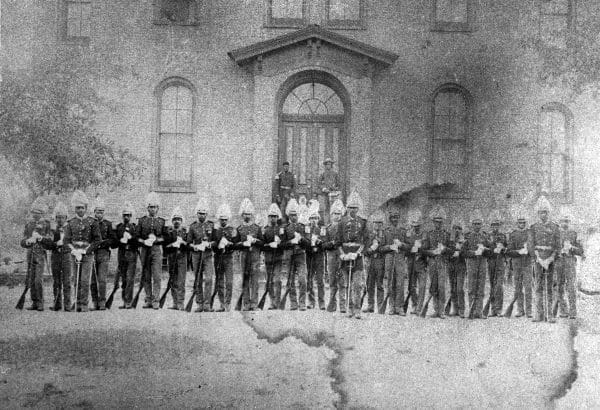

After the Civil War, southern states slowly began to rebuild their state militias. Among these new militia organizations were a limited number of black units, including three in Alabama: the Magic City Guards in Birmingham, Gilmer’s Rifles in Mobile, and the Capital City Guards in Montgomery. Like their counterparts throughout the South, members of these militias endured neglect and persistent discrimination from state government and white military organizations. Members often suffered from the same racism found in their local communities. Despite the rise of Jim Crow laws, however, two of the three Alabama black militia units remained active into the late-nineteenth century (Gilmer’s Rifles) and early-twentieth century (Capital City Guards), and their longevity owed much to the political skills and determination of their leaders, Reuben Romulus Mims of Mobile and Abraham Calvin Caffey of Montgomery.

Capital City Guards

After the Civil War, southern states slowly began to rebuild their state militias. Among these new militia organizations were a limited number of black units, including three in Alabama: the Magic City Guards in Birmingham, Gilmer’s Rifles in Mobile, and the Capital City Guards in Montgomery. Like their counterparts throughout the South, members of these militias endured neglect and persistent discrimination from state government and white military organizations. Members often suffered from the same racism found in their local communities. Despite the rise of Jim Crow laws, however, two of the three Alabama black militia units remained active into the late-nineteenth century (Gilmer’s Rifles) and early-twentieth century (Capital City Guards), and their longevity owed much to the political skills and determination of their leaders, Reuben Romulus Mims of Mobile and Abraham Calvin Caffey of Montgomery.

Initially, all post-war militias consisted solely of volunteers and had no state guidance or interest. There were no central organizations or common uniforms and no state funds. In 1881, however, Alabama organized its volunteer militias as the Alabama State Troops (AST). With the 1882 election of Gov. Edward A. O’Neal, Alabama’s political climate settled into a “safe status quo,” making it practical to expand and support an organized state militia.

Reuben Romulus Mims

The first of Alabama’s three black companies, the Magic City Guards, was organized in 1883 in Birmingham. Capt. James A. Scott, a lawyer and editor of the first black Democratic newspaper in Alabama, commanded it. Within the year, however, the AST dropped him from its roster because of excessive absences from duty, and the lack of leadership severely hampered the unit. The state government formally disbanded the Magic City Guards for inefficiency on August 6, 1887, and it was never reorganized.

Reuben Romulus Mims

The first of Alabama’s three black companies, the Magic City Guards, was organized in 1883 in Birmingham. Capt. James A. Scott, a lawyer and editor of the first black Democratic newspaper in Alabama, commanded it. Within the year, however, the AST dropped him from its roster because of excessive absences from duty, and the lack of leadership severely hampered the unit. The state government formally disbanded the Magic City Guards for inefficiency on August 6, 1887, and it was never reorganized.

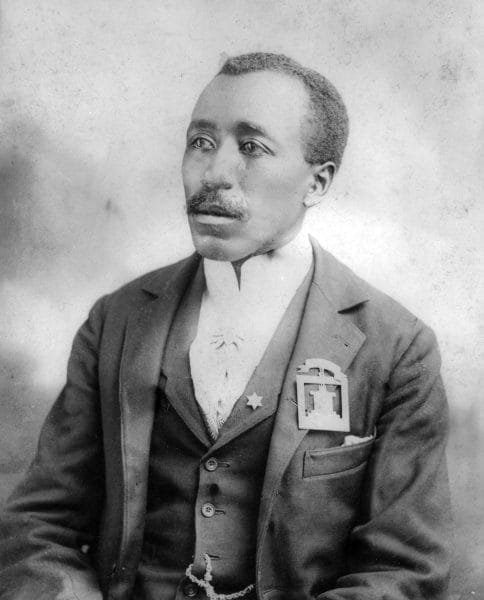

Mobile’s Gilmer’s Rifles was also officially organized in 1883, initially under the command of William T. Foster, a Creole cotton sampler. The following year, Reuben Romulus Mims was elected captain of the company. In 1895, he was promoted to major of the AST black battalion, becoming the highest-ranking black officer in the state troops. The son of Georgia-born Lida Lee, Mims was born in Aberdeen, Mississippi, in July 1854, and by the 1870s he had moved to Mobile and become involved in the city’s politics during the final years of Congressional Reconstruction. In 1882, his loyalty to Republican candidates was rewarded with an appointment as a letter carrier, a position he held until his death. An enthusiastic and dedicated Mason, Mims rose to the highest rank in black Freemasonry in the state and served as grand master for 15 years.

In Montgomery, after several false starts, the Capital City Guards was officially organized in 1885. Its first commander was Joseph L. Ligon, a 40-year-old African American hackman and racehorse stable owner who also owned a house in the city. Among the men of the newly formed Montgomery company was Abraham Calvin Caffey, a property-owning building contractor (he did repair work on the state capitol building) who rose through the ranks to become a captain when he was elected the company’s commander in 1894. A respected member of Montgomery’s black community, Caffey was the Sunday-school superintendent of Old Ship A.M.E. Zion Church, Montgomery’s largest African American church. He was also active in fraternal affairs (especially the Masons) and had influential friends, including Booker T. Washington.

Abraham Calvin Caffey

Both Mims and Caffey excelled in their leadership roles, as the significant and sustained membership in the two companies indicates: muster rolls show that each company had between 50 and 100 men. Militia members, most of whom were privates, were likely to be employed primarily at skilled and unskilled labor, with a few working as railroad porters, postal carriers, and barbers. They were enthusiastic militiamen, often drilling and marching more often and with higher rates of participation than the men in the white companies.

Abraham Calvin Caffey

Both Mims and Caffey excelled in their leadership roles, as the significant and sustained membership in the two companies indicates: muster rolls show that each company had between 50 and 100 men. Militia members, most of whom were privates, were likely to be employed primarily at skilled and unskilled labor, with a few working as railroad porters, postal carriers, and barbers. They were enthusiastic militiamen, often drilling and marching more often and with higher rates of participation than the men in the white companies.

In 1895, the state government reorganized the Montgomery and Mobile companies into a single battalion commanded by Mims, whose promotion to major made him the highest-ranking black officer in the AST. Although administratively part of the state troops, the black battalion was segregated from the white units and received inferior support, equipment, and training. In addition, the African American militiamen received a substantially lower per capita appropriation than that allotted to their white counterparts. The state also conducted separate encampments and official inspections for the two black companies independent from those of the white troops, and these occurred less frequently. During the 1895 and 1896 Mobile encampments, for example, white militiamen held target practice within the camp, and each man was given 10 rounds; the black militiaman received five rounds of outdated ammunition and fired at targets set up in Mobile Bay.

Despite those conditions, Alabama’s black militia companies maintained their reputations as well drilled, well disciplined, and well uniformed. And although they maintained a diligent training schedule, the state’s black companies were never mobilized to quell a civil disturbance, an important role for state troops, because of the race-based fear that the white populace would be offended by the presence of armed black soldiers. During the two decades that the black troops were official members of the AST, the state militia was called for active service more than 40 times—to quell mob violence, to provide prisoner protection, and to protect property after a cyclone—but only white troops were authorized to respond.

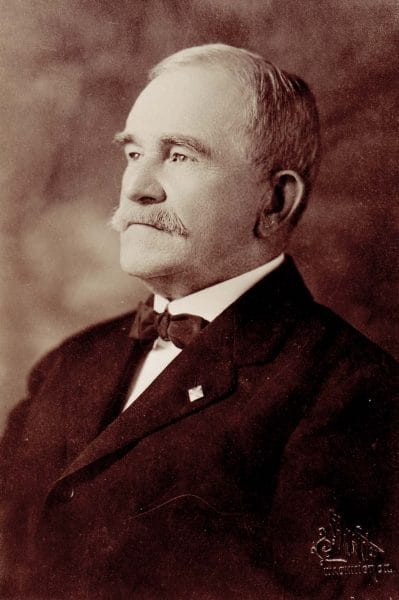

Joseph F. Johnston

On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. Many Alabama African Americans viewed the conflict as an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism. Gov. Joseph F. Johnston agreed to accept black volunteers because black disfranchisement was not yet complete (and he was facing re-election), and he lacked enough white troops to meet federal quotas in the newly created Alabama National Guard (ANG)—the AST having been renamed in February 1897.

Joseph F. Johnston

On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. Many Alabama African Americans viewed the conflict as an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism. Gov. Joseph F. Johnston agreed to accept black volunteers because black disfranchisement was not yet complete (and he was facing re-election), and he lacked enough white troops to meet federal quotas in the newly created Alabama National Guard (ANG)—the AST having been renamed in February 1897.

In both Mobile and Montgomery the initial response by the two black companies was enthusiastic: Mims and Caffey indicated to the governor that their troops would sign up en masse. Their enthusiasm waned, however, after the appointment of Capt. Robert Gage, the militarily inexperienced white son-in-law of a prominent Mobile physician, as commanding officer of the Mobile company. The members of Gilmer’s Rifles reversed their decision and, sharing the outrage of many blacks across the nation, refused to fight unless commanded by Mims, an action that proved to be the death knell for the company.

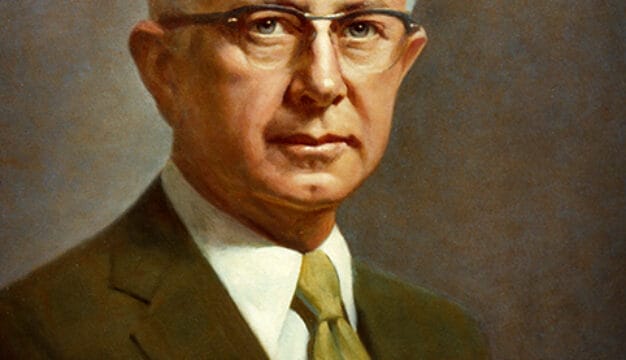

Francis Gordon Caffey

In Montgomery, all but a dozen Capital City Guards accepted a white commander. When the governor commissioned Harvard-educated lawyer Francis Gordon Caffey (no apparent relation to Abraham Caffey) to command the black company, Abraham Caffey retired with a few others; the rest of the unit entrained for Mobile where they mustered in as Company A of the Third Alabama Voluntary Regiment. Although the black regiment never reached a battlefield or saw foreign duty during the Spanish-American War, it remained in service longer than any other Alabama volunteer unit, mustering out in March 1899.

Francis Gordon Caffey

In Montgomery, all but a dozen Capital City Guards accepted a white commander. When the governor commissioned Harvard-educated lawyer Francis Gordon Caffey (no apparent relation to Abraham Caffey) to command the black company, Abraham Caffey retired with a few others; the rest of the unit entrained for Mobile where they mustered in as Company A of the Third Alabama Voluntary Regiment. Although the black regiment never reached a battlefield or saw foreign duty during the Spanish-American War, it remained in service longer than any other Alabama volunteer unit, mustering out in March 1899.

Despite praise for their efforts and skill, the black militiamen were not protected from the rising tide of racial discrimination. Gilmer’s Rifles was never reactivated, but Mims continued in his position as commander of half a battalion of the Montgomery Capital City Guards until his death on March 9, 1901. The Montgomery company remained active for another four years, as they were probably viewed as a “useful” political tool for the governor. But on November 8, 1905, despite the legal opinion of ANG Judge Advocate Col. Claude E. Hamilton, a Greenville lawyer, that the Capital City Guards was indeed a legitimate ANG unit, Adjutant Gen. William W. Brandon overruled the decision and declared the last black militia company in the Deep South an “ineffective organization” and mustered it out.

The hardening boundaries of segregation and the denial of constitutional rights, including total disfranchisement of African Americans in 1901, dashed the hopes of many blacks who sought to gain equal citizenship through military service. Their exclusion from the ANG would last another six decades, until the civil rights movement and federal prodding forced the state’s military establishment to re-evaluate the racial composition of their troops.

Further Reading

- Gatewood, Willard B., Jr. “Alabama’s ‘Negro Soldier Experiment,’ 1898–1899.” Journal of Negro History (October 1972): 333–51.

- Muskat, Beth Taylor. “The Last March: The Demise of the Black Militia in Alabama.” Alabama Review 43 (January 1990): 18–34.

- ———. “Mobile’s Black Militia: Major R. R. Mims and Gilmer’s Rifles.” Alabama Review 57 (July 2004): 183–205.