Augusta Jane Evans Wilson

Augusta Jane Evans

Augusta Jane Evans Wilson (1835-1909) was one of the most popular American novelists of the nineteenth century and certainly the most successful Alabama writer of her time. Her literary fame made her a prominent citizen of Mobile, where she spent most of her life. Like many popular women authors of her day, Evans Wilson wrote in a genre known as domestic, or sentimental, fiction, but her writing displayed a breadth of knowledge uncommon among her peers. She published nine novels, of which Beulah and St. Elmo are the best-known.

Augusta Jane Evans

Augusta Jane Evans Wilson (1835-1909) was one of the most popular American novelists of the nineteenth century and certainly the most successful Alabama writer of her time. Her literary fame made her a prominent citizen of Mobile, where she spent most of her life. Like many popular women authors of her day, Evans Wilson wrote in a genre known as domestic, or sentimental, fiction, but her writing displayed a breadth of knowledge uncommon among her peers. She published nine novels, of which Beulah and St. Elmo are the best-known.

Augusta Jane Evans was born on May 8, 1835, in Columbus, Georgia. She was the oldest of eight children born to Matthew “Matt” Ryan Evans and Sarah Skrine Howard Evans. Both parents were from planter families, and Evans was a partner in a successful mercantile firm. Augusta and her siblings seemed destined for a life of privilege, but her father’s business went bankrupt after the Panic of 1837. Although his family was not impoverished, Matt never regained his earlier level of success. Augusta was permanently marked by the loss of her family’s status and wealth.

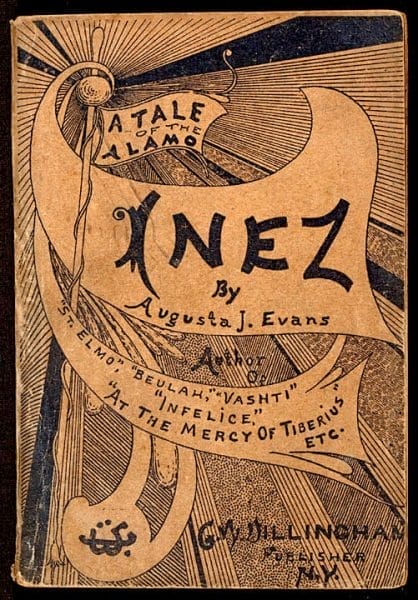

Inez: A Tale of the Alamo

Like many Americans who suffered financial reverses in the economically volatile early nineteenth century, Matt Evans decided to move west to rebuild his fortune. In the early 1840s, the Evanses lived at Oswichee (then spelled “Oswitchee”) in Russell County, Alabama. In 1846 they moved to San Antonio, Texas, where business was booming owing to the large numbers of settlers who had moved into the area after the Texas War of Independence (1835-36), and the thriving trade in military goods at the start of the Mexican War (1846-48). Life on the frontier, however, was rugged and dangerous. In 1849, Matt Evans moved his family back east, this time to the bustling cotton port of Mobile.

Inez: A Tale of the Alamo

Like many Americans who suffered financial reverses in the economically volatile early nineteenth century, Matt Evans decided to move west to rebuild his fortune. In the early 1840s, the Evanses lived at Oswichee (then spelled “Oswitchee”) in Russell County, Alabama. In 1846 they moved to San Antonio, Texas, where business was booming owing to the large numbers of settlers who had moved into the area after the Texas War of Independence (1835-36), and the thriving trade in military goods at the start of the Mexican War (1846-48). Life on the frontier, however, was rugged and dangerous. In 1849, Matt Evans moved his family back east, this time to the bustling cotton port of Mobile.

Evans did not receive much schooling because of her family circumstances and frequent illness. Her mother, a well-educated woman, tutored her at home, and she read avidly. She had a keen intellect and developed a great love for philosophy, history, and literature. Evans was deeply attached to her mother and later in life stated that she owed all of her accomplishments to her mother’s influence.

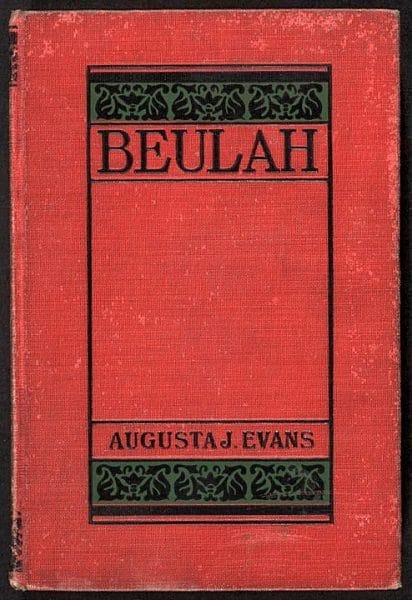

Beulah

At the age of 15, Evans began her first novel, Inez: A Tale of the Alamo. She hoped that sales of the novel would augment the family’s income, but she was disappointed. Inez (1855) was a stilted, anti-Catholic romance that sold poorly. (Later in life, Evans Wilson abandoned her anti-Catholic views and developed a respect for Catholicism.) Although Evans’s first book was a failure, her second, Beulah, was a remarkable success. Published in 1859, the novel sold 22,000 copies in the first nine months and received high praise from reviewers. Set in the 1850s in an unnamed Alabama city (probably Mobile), Beulah is essentially a religious novel about a fiery young woman’s search for ultimate truth. The heroine, Beulah Benton, abandons her Christian faith as she studies the writings of skeptical philosophers, but she continues her spiritual search to the point of exhaustion. Only when she recognizes that ultimate truth is beyond the grasp of human reason does she return to Christianity and accept the love of her suitor. Beulah’s conversion story is rooted in the author’s personal experience. Around 1855, Evans experienced a severe crisis of faith, probably brought on by her own study of non-Christian philosophy. In early 1856, she decided to reject philosophy and turned instead to Christian revelation. Two years later she returned to the Methodism of her childhood and remained a strong Methodist for the rest of her life.

Beulah

At the age of 15, Evans began her first novel, Inez: A Tale of the Alamo. She hoped that sales of the novel would augment the family’s income, but she was disappointed. Inez (1855) was a stilted, anti-Catholic romance that sold poorly. (Later in life, Evans Wilson abandoned her anti-Catholic views and developed a respect for Catholicism.) Although Evans’s first book was a failure, her second, Beulah, was a remarkable success. Published in 1859, the novel sold 22,000 copies in the first nine months and received high praise from reviewers. Set in the 1850s in an unnamed Alabama city (probably Mobile), Beulah is essentially a religious novel about a fiery young woman’s search for ultimate truth. The heroine, Beulah Benton, abandons her Christian faith as she studies the writings of skeptical philosophers, but she continues her spiritual search to the point of exhaustion. Only when she recognizes that ultimate truth is beyond the grasp of human reason does she return to Christianity and accept the love of her suitor. Beulah’s conversion story is rooted in the author’s personal experience. Around 1855, Evans experienced a severe crisis of faith, probably brought on by her own study of non-Christian philosophy. In early 1856, she decided to reject philosophy and turned instead to Christian revelation. Two years later she returned to the Methodism of her childhood and remained a strong Methodist for the rest of her life.

Georgia Cottage

With her literary success, Evans was at last able to provide for her family’s needs. She purchased a house, Georgia Cottage (which still stands on Springhill Avenue in Mobile and was later the childhood home of Eugene Sledge), and made plans for a long-desired trip to Europe. She also became engaged to New York editor James Reed Spalding, who shared her zeal for the Christian faith. Evans’s happy plans unraveled, however, as the nation plunged toward civil war. As “a most uncompromising secessionist,” she broke off her engagement with Spalding because of their political differences.

Georgia Cottage

With her literary success, Evans was at last able to provide for her family’s needs. She purchased a house, Georgia Cottage (which still stands on Springhill Avenue in Mobile and was later the childhood home of Eugene Sledge), and made plans for a long-desired trip to Europe. She also became engaged to New York editor James Reed Spalding, who shared her zeal for the Christian faith. Evans’s happy plans unraveled, however, as the nation plunged toward civil war. As “a most uncompromising secessionist,” she broke off her engagement with Spalding because of their political differences.

During the Civil War, Evans devoted herself to the Confederate cause as a volunteer organizer, nurse, and propagandist (she wrote several newspaper articles in support of the Confederacy). She also corresponded with two noted Confederate leaders, Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard (who was instrumental in developing the submarine H. L. Hunley) and Alabama congressman J. L. M. Curry, regarding her views on military and political subjects. Despite the demands of these activities, she continued to write fiction. In 1864 her third novel, Macaria; or Altars of Sacrifice, was published separately in the Union and the Confederacy. A pro-Confederate propaganda novel, it is also, like Beulah, a story of Christian conversion.

Augusta Wilson in Mobile

The Civil War left Evans impoverished and depressed. Her immediate family had all survived the war, but her beloved brother Howard (“Bud”) was permanently disabled. Despite her troubles, Evans again devoted herself to writing. In 1867 she published the most successful of all her novels, St. Elmo. In it, Evans depicted a moral struggle between good and evil. The novel’s male protagonist, St. Elmo Murray, is at first a cynical and cruel man, but he is gradually converted to Christianity through his love for the virtuous heroine, Edna Earle. Edna willingly gives up her literary career when she marries St. Elmo, and this choice reflects Evans’s belief that women were happiest, and most powerful, when they devoted themselves to their families and homes. This was a common idea in the mid-nineteenth century, and is it one of the major themes of domestic fiction.

Augusta Wilson in Mobile

The Civil War left Evans impoverished and depressed. Her immediate family had all survived the war, but her beloved brother Howard (“Bud”) was permanently disabled. Despite her troubles, Evans again devoted herself to writing. In 1867 she published the most successful of all her novels, St. Elmo. In it, Evans depicted a moral struggle between good and evil. The novel’s male protagonist, St. Elmo Murray, is at first a cynical and cruel man, but he is gradually converted to Christianity through his love for the virtuous heroine, Edna Earle. Edna willingly gives up her literary career when she marries St. Elmo, and this choice reflects Evans’s belief that women were happiest, and most powerful, when they devoted themselves to their families and homes. This was a common idea in the mid-nineteenth century, and is it one of the major themes of domestic fiction.

In 1868 Augusta Evans married Col. Lorenzo Madison Wilson, a 60-year-old widower and prosperous businessman. She moved into Wilson’s Springhill Avenue mansion, Ashland. The marriage appears to have been happy. Evans Wilson enjoyed her new role as mistress of Ashland and helped to raise her husband’s youngest child, Fannie (she had no children of her own). She encouraged younger women to enter the field of nursing, supported a number of Mobile charities, and cultivated flowers with her husband. Unlike Edna Earle, she also continued to write, although at a slower pace. During her years at Ashland, Evans Wilson produced three more novels: Vashti; or, Until Death Us Do Part (1869), Infelice (1875), and At the Mercy of Tiberius (1887). By this time she had many devoted readers, and although these later novels were not as popular as Beulah and St. Elmo, all of them sold quite well.

After her husband’s death in 1891, Evans Wilson moved to a house in downtown Mobile, where she lived with her brother Howard and wrote her last works, the novel A Speckled Bird (1902) and the novelette Devota (1907). She was almost blind when she wrote Devota (she dictated the story to her niece), and her health continued to decline. On May 9, 1909, Evans Wilson died of a heart attack. She lies buried next her brother Howard in Mobile’s Magnolia Cemetery.

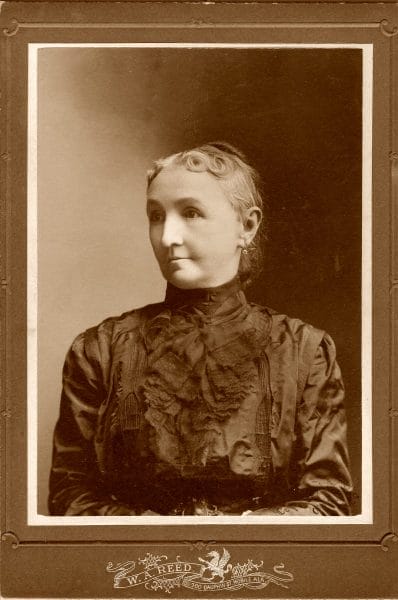

Augusta Wilson Portrait

Evans Wilson’s novels are not considered great literature, but they are interesting for what they can teach us about nineteenth-century American tastes and values. Her religious convictions and conservative political views were formed in the pre-Civil War South. She opposed “woman suffrage” (votes for women), even as increasing numbers of women came to support this cause toward the end of the century. Her literary style, which was very elaborate and traditional in its romantic idealism, earned her many admirers. It also drew harsh critics, who called her writing pretentious and artificial. Evans Wilson believed that novelists ought to “elevate” society by presenting their readers with “the very highest, noblest types of human nature.” All the heroines and heroes of her novels were or became virtuous Christians who did what they believed was right no matter how much it cost them. Evans Wilson hoped that her characters would inspire her readers to the same kind of heroism.

Augusta Wilson Portrait

Evans Wilson’s novels are not considered great literature, but they are interesting for what they can teach us about nineteenth-century American tastes and values. Her religious convictions and conservative political views were formed in the pre-Civil War South. She opposed “woman suffrage” (votes for women), even as increasing numbers of women came to support this cause toward the end of the century. Her literary style, which was very elaborate and traditional in its romantic idealism, earned her many admirers. It also drew harsh critics, who called her writing pretentious and artificial. Evans Wilson believed that novelists ought to “elevate” society by presenting their readers with “the very highest, noblest types of human nature.” All the heroines and heroes of her novels were or became virtuous Christians who did what they believed was right no matter how much it cost them. Evans Wilson hoped that her characters would inspire her readers to the same kind of heroism.

Romantic moralism is the most striking characteristic of Evans Wilson’s novels. Her understanding of her moral duty as an author led her to continue writing romantic novels long after other American writers had adopted the more realistic style that became dominant after the Civil War. Despite her old-fashioned style and conservative views (she rejected the feminist fiction being created by younger women writers such as Kate Chopin and Charlotte Perkins Gilman at the turn of the century), Evans Wilson maintained a loyal readership. Her books continued in print into the middle of the twentieth century, and five of them were made into films between 1910 and 1923. Today, few people read her work for pleasure or inspiration; it is primarily the subject of scholarly study.

Further Reading

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. Introduction to Macaria, or Altars of Sacrifice, by Augusta Jane Evans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

- Fidler, William Perry. Augusta Evans Wilson, 1835–1909: A Biography. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

- Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth. Introduction to Beulah, by Augusta Jane Evans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

- Riepma, Anna Sophia Roelina. Fire and Fiction: Augusta Jane Evans in Context. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000.

- Sexton, Rebecca Grant, ed. A Southern Woman of Letters: The Correspondence of Augusta Jane Evans Wilson. Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2002.