Battle of Horseshoe Bend

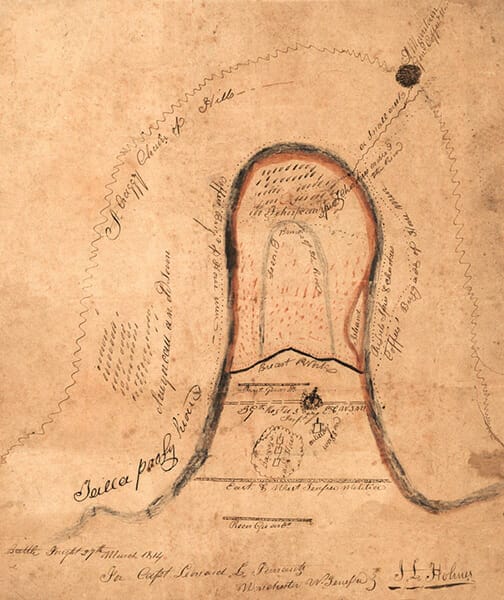

Map of Horseshoe Bend

On the morning of March 27, 1814, in what is now Tallapoosa County, Gen. Andrew Jackson and an army consisting of Tennessee militia, United States regulars, and Cherokee and Lower Creek allies attacked Chief Menawa and his Upper Creek, or Red Stick, warriors fortified in the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River. Facing overwhelming odds, the Red Sticks fought bravely yet ultimately lost the battle. More than 800 Upper Creek warriors died at Horseshoe Bend defending their homeland. This was the final battle of the Creek War of 1813-14. The victory at Horseshoe Bend brought Andrew Jackson national attention and helped elect him president in 1828. In treaty signed after the battle, known as the Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creeks ceded more than 21 million acres of land to the United States.

Map of Horseshoe Bend

On the morning of March 27, 1814, in what is now Tallapoosa County, Gen. Andrew Jackson and an army consisting of Tennessee militia, United States regulars, and Cherokee and Lower Creek allies attacked Chief Menawa and his Upper Creek, or Red Stick, warriors fortified in the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River. Facing overwhelming odds, the Red Sticks fought bravely yet ultimately lost the battle. More than 800 Upper Creek warriors died at Horseshoe Bend defending their homeland. This was the final battle of the Creek War of 1813-14. The victory at Horseshoe Bend brought Andrew Jackson national attention and helped elect him president in 1828. In treaty signed after the battle, known as the Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creeks ceded more than 21 million acres of land to the United States.

Long before the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Creeks (also known as Muskogee) people lived in a loose confederation of towns along the rivers of west-central Georgia and east-central Alabama. Anglo-American settlers divided the Creek towns geographically into two groups: the Lower Towns along the Chattahoochee, Flint, and Ocmulgee Rivers; and the Upper Towns along the Tallapoosa, Coosa, and Alabama Rivers. In 1811, Shawnee military leader Tecumseh visited the southeastern tribes hoping to encourage them to return to their ancient traditions as well as drive the Americans from their ancestral lands. Many individuals in the Upper Creek Towns responded favorably to Tecumseh. When war broke out between the United States and Great Britain in 1812, a few Creek warriors joined Tecumseh and the British in fighting the Americans. The War of 1812 in turn brought on the Creek War of 1813-14, which began as a civil war between Creeks in both the Upper and Lower towns friendly to the United States and a faction in the Upper Towns called the Red Sticks, hostile towards the Americans. Many scholars believe that the Red Sticks took their name from their red-painted war clubs.

Massacre at Fort Mims

On July 27, 1813, a small force of Mississippi Territorial Militia ambushed a party of Red Sticks returning from Pensacola with Spanish ammunition and supplies at Burnt Corn Creek, located near the border of what is now Conecuh and Escambia Counties. One month later, on August 30, the Red Sticks retaliated by killing 250 Creek and American settlers at Fort Mims, a stockade just north of Mobile. The Fort Mims Massacre, as it came to be known, turned the Creek civil war into a larger conflict, with U.S. forces from Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory launching a three-pronged assault into Creek territory. The governor of Tennessee appointed Andrew Jackson, a prominent state politician and militia officer, to lead a portion of the state’s militia into Creek country. Jackson fought a slow and difficult campaign south along the Coosa River. In March 1814, reinforced by regular soldiers of the Thirty-ninth United States Infantry, Jackson left the Coosa with a force of 3,300 men, including 500 Cherokee and 100 Lower Creek warriors allied to the United States. He intended to attack a Red Stick refuge and defensive position in the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River.

Massacre at Fort Mims

On July 27, 1813, a small force of Mississippi Territorial Militia ambushed a party of Red Sticks returning from Pensacola with Spanish ammunition and supplies at Burnt Corn Creek, located near the border of what is now Conecuh and Escambia Counties. One month later, on August 30, the Red Sticks retaliated by killing 250 Creek and American settlers at Fort Mims, a stockade just north of Mobile. The Fort Mims Massacre, as it came to be known, turned the Creek civil war into a larger conflict, with U.S. forces from Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory launching a three-pronged assault into Creek territory. The governor of Tennessee appointed Andrew Jackson, a prominent state politician and militia officer, to lead a portion of the state’s militia into Creek country. Jackson fought a slow and difficult campaign south along the Coosa River. In March 1814, reinforced by regular soldiers of the Thirty-ninth United States Infantry, Jackson left the Coosa with a force of 3,300 men, including 500 Cherokee and 100 Lower Creek warriors allied to the United States. He intended to attack a Red Stick refuge and defensive position in the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River.

On March 26, Jackson’s army camped six miles northwest of Horseshoe Bend. Menawa, a respected war leader from the town of Okfuskee, waited at the bend with 1,000 Red Stick warriors and at least 350 women and children. Beginning in December 1813, people from six Upper Creek towns—Newyaucau, Oakfuskee, Oakchaya, Eufaula, Fishponds, and Hillabee—had gathered at Horseshoe Bend for protection. At the toe of the bend, they built a temporary village, which they called Tohopeka, consisting of about 300 log houses. They constructed a log-and-dirt barricade nearly 400 yards long across the narrow neck of the bend. In this fortified place, the Red Sticks hoped to defeat an attacking army or at least delay the attackers while the women, children, and older men escaped down river.

John Coffee

At 6:30 on the morning of March 27, Jackson divided his army. He ordered Gen. John Coffee‘s force of 700 mounted riflemen and 600 allied warriors to cross the Tallapoosa about two and one half miles downriver from Tohopeka and surround the village. The 2,000 remaining men, led by Jackson, marched directly for the neck of the horseshoe and the barricade. Jackson knew that it would be difficult to attack the imposing barricade. He chose the Thirty-ninth Infantry, the most disciplined and best trained of his soldiers, to lead the assault, including Maj. Lemuel Montgomery, who would be among the first to fall and would be honored by having Montgomery County named in his honor. Before sending them forward, he decided to blow a hole in the wall with his cannon. The bombardment began at 10:30 a.m. For two hours, the guns fired iron shot at the barricade protecting the Red Sticks, who waited and shouted at the army to meet them in hand-to-hand combat. Only perhaps a third of the 1,000 warriors defending the barricade possessed a musket or rifle.

John Coffee

At 6:30 on the morning of March 27, Jackson divided his army. He ordered Gen. John Coffee‘s force of 700 mounted riflemen and 600 allied warriors to cross the Tallapoosa about two and one half miles downriver from Tohopeka and surround the village. The 2,000 remaining men, led by Jackson, marched directly for the neck of the horseshoe and the barricade. Jackson knew that it would be difficult to attack the imposing barricade. He chose the Thirty-ninth Infantry, the most disciplined and best trained of his soldiers, to lead the assault, including Maj. Lemuel Montgomery, who would be among the first to fall and would be honored by having Montgomery County named in his honor. Before sending them forward, he decided to blow a hole in the wall with his cannon. The bombardment began at 10:30 a.m. For two hours, the guns fired iron shot at the barricade protecting the Red Sticks, who waited and shouted at the army to meet them in hand-to-hand combat. Only perhaps a third of the 1,000 warriors defending the barricade possessed a musket or rifle.

Chief Menawa

Meanwhile, across the river from Tohopeka, three of Coffee’s Cherokee warriors slipped into the river and swam to canoes lying on the opposite bank. Using the stolen canoes, the Cherokee and Lower Creek warriors crossed the river in increasing numbers, attacking and burning Tohopeka from the rear. At 12:30 p.m., Jackson launched his attack, after seeing smoke rising above the treetops and hearing gunshots. Drummers signaled the advance, and with bayonets fixed, the regulars swept forward. After a few minutes of brutal fighting, the Red Sticks fell back to the interior of the bend. They fought desperately but were outgunned and vastly outnumbered. Many tried to escape into the river, but Coffee’s men shot them before they reached the opposite bank. The fighting raged nearly six hours before darkness fell and ended the battle.

Chief Menawa

Meanwhile, across the river from Tohopeka, three of Coffee’s Cherokee warriors slipped into the river and swam to canoes lying on the opposite bank. Using the stolen canoes, the Cherokee and Lower Creek warriors crossed the river in increasing numbers, attacking and burning Tohopeka from the rear. At 12:30 p.m., Jackson launched his attack, after seeing smoke rising above the treetops and hearing gunshots. Drummers signaled the advance, and with bayonets fixed, the regulars swept forward. After a few minutes of brutal fighting, the Red Sticks fell back to the interior of the bend. They fought desperately but were outgunned and vastly outnumbered. Many tried to escape into the river, but Coffee’s men shot them before they reached the opposite bank. The fighting raged nearly six hours before darkness fell and ended the battle.

More than 800 Red Stick warriors were killed, with 557 counted on the battlefield and an estimated 300 shot in the river. Of Jackson’s troops, 49 were killed and 154 wounded. The 350 Upper Creek women and children became prisoners of the Cherokee and Lower Creek warriors. Chief Menawa was wounded seven times but escaped the slaughter. By his own account, he lay among the dead until nightfall and then crawled to the river, climbed into a canoe, and disappeared into the darkness. Menawa remained a prominent leader in Creek society and continued to live along the Tallapoosa River until 1836, when he was forced to relocate to Indian Territory in what is today Oklahoma.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend effectively ended the Creek War and made Andrew Jackson a national hero. He was made a major general in the U.S. Army and on January 8, 1815, defeated the British forces at the Battle of New Orleans. The battles of Horseshoe Bend and New Orleans made Jackson popular enough to be elected as the seventh president of the United States in 1828. During his presidency, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, a law providing for the removal of all the southeastern Indian tribes. A few months after Horseshoe Bend, on August 9, 1814, Andrew Jackson and a gathering of Creek chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Thousands of American settlers poured into the vast ceded acreage, with much of the land becoming the state of Alabama in 1819. Today, the battlefield is preserved by the National Park Service as Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, near Dadeville.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend effectively ended the Creek War and made Andrew Jackson a national hero. He was made a major general in the U.S. Army and on January 8, 1815, defeated the British forces at the Battle of New Orleans. The battles of Horseshoe Bend and New Orleans made Jackson popular enough to be elected as the seventh president of the United States in 1828. During his presidency, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, a law providing for the removal of all the southeastern Indian tribes. A few months after Horseshoe Bend, on August 9, 1814, Andrew Jackson and a gathering of Creek chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Thousands of American settlers poured into the vast ceded acreage, with much of the land becoming the state of Alabama in 1819. Today, the battlefield is preserved by the National Park Service as Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, near Dadeville.

Further Reading

- Halbert, H. S., and T. H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. 1895. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1969.

- Holland, James W. Andrew Jackson and the Creek War: Victory at the Horseshoe. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968.

- Martin, Joel W. Sacred Revolt: The Muskogees’ Struggle for a New World. Boston: Beacon Press, 1991.

- Stiggins, George. Creek Indian History: A Historical Narrative of the Genealogy, Traditions and Downfall of the Ispocoga or Creek Indians. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Public Library Press, 1989.