Thomas Haughey

Thomas Haughey

Thomas Haughey (1826-1869) was in the first cohort of U.S. congressmen elected from Alabama following the state’s 1868 readmission to the Union after the Civil War. Haughey served one term as a Republican representing Alabama’s Sixth Congressional District and voted with his fellow Republicans in support of the Fourteenth Amendment, to pass the Fifteenth Amendment, and to impeach Pres. Andrew Johnson. A native of Scotland, Haughey immigrated to the United States, moved to Alabama, and became a doctor and a surgeon. During the Civil War, he served in the U.S. Army. When running for reelection in 1869, he was shot during an altercation while giving a speech in Courtland, Lawrence County, and died soon after.

Thomas Haughey

Thomas Haughey (1826-1869) was in the first cohort of U.S. congressmen elected from Alabama following the state’s 1868 readmission to the Union after the Civil War. Haughey served one term as a Republican representing Alabama’s Sixth Congressional District and voted with his fellow Republicans in support of the Fourteenth Amendment, to pass the Fifteenth Amendment, and to impeach Pres. Andrew Johnson. A native of Scotland, Haughey immigrated to the United States, moved to Alabama, and became a doctor and a surgeon. During the Civil War, he served in the U.S. Army. When running for reelection in 1869, he was shot during an altercation while giving a speech in Courtland, Lawrence County, and died soon after.

Haughey was born in 1826 in Glasgow, Scotland. When he was 15, he and his father immigrated to the United States and initially settled in New York City. The names of his parents and number of siblings are not listed among available resources. In 1841, Haughey moved to Jefferson County and after some years of self-education began attending New Orleans Medical College. In 1858, he graduated as a physician and surgeon and returned to Alabama, starting his own medical practice in Elyton, Jefferson County. Sometime in the 1850s, Haughey married Elizabeth Martin from South Carolina according to Census records. The couple had at least two, and possibly four children, according to Morgan County probate court estate records.

After Abraham Lincoln’s election, Alabama seceded from the Union with other Deep South states, but Haughey remained a staunch Unionist. Outspoken about his views, Haughey joined the Union League, an organization that promoted Union and Republican causes. Resistance to his Union League membership and political views forced Haughey to leave his home and flee to Kentucky. While there, Haughey joined the U.S. Army as a surgeon, serving in the Third Regiment of the Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. In February 1865, Haughey was honorably discharged from service.

Rather than returning to Elyton, Haughey settled in Decatur, Morgan County, and continued his medical practice. Although the Civil War was over, the nation was still in turmoil as the U.S. Army and Congress worked to readmit the formerly Confederate States, in an era known as Reconstruction. Haughey’s involvement in state and local politics during this time prompted his election as a delegate to the Alabama State Constitutional Convention in 1867. After the convention adopted a new constitution in 1868 that paved the way for Alabama’s readmission to the Union, Haughey decided to run for Congress.

Campaigning as a Republican, Haughey was elected and, on July 21, 1868, became a member of the Fortieth Congress. It had been seated in March 1867, but Alabama did not rejoin the Union until July 13, 1868, when the state legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. He represented Alabama’s Sixth Congressional District, which at the time consisted of Blount, Franklin, Jefferson, Lauderdale, Lawrence, Limestone, Marion, Walker, and Winston Counties. The district had been reconfigured and sat vacant since Alabama seceded in 1861 but had been previously held by Unionist Williamson Robert Winfield Cobb. He was reportedly the last member of the Alabama delegation to leave Washington, D.C., following the state’s secession. Haughey served on the Committee on the Expenditures of Public Buildings.

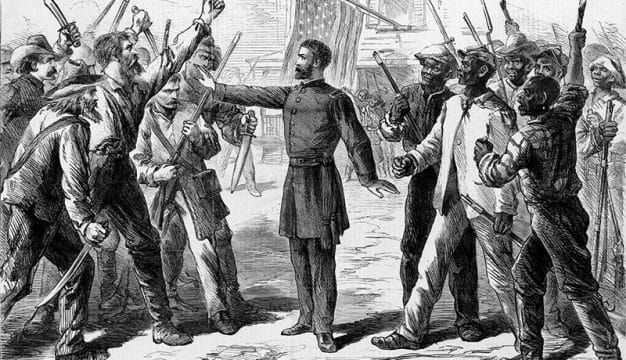

Even before he began his work in Congress, Haughey found himself embroiled in controversy. Congress had been debating the validity of the 1867 Alabama State Constitutional Convention and the legitimacy of its congressional elections, given that many former Confederates were still disenfranchised and that most participants in the election were Unionists, Republicans, and newly freed African Americans. In a March 1868 letter to Congress, Haughey described the contentious political climate in Alabama as campaigns of terrorism and intimidation sought to prevent African Americans in particular from voting. Haughey firmly believed any former Confederate soldiers or officials should not be re-enfranchised, whereas some members of Congress sought to prevent Alabama’s readmission.

During his short tenure, Haughey participated in some significant votes. On the day he was seated, he voted in favor of adopting a preamble to the Fourteenth Amendment and adding the amendment to the Constitution. (It was passed by Congress in 1866 and later ratified by the states to guarantee citizenship to formerly enslaved individuals.) Several days later, Haughey voted for a new House attempt to impeach Democratic Pres. Andrew Johnson, but that effort failed to gain traction in the Senate, which had just acquitted Johnson that May. Haughey also voted that day to reduce the presence of the Freedman’s Bureau except for educational activities and some administrative functions. In February 1869, he voted to pass the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed suffrage for African America men. He also implored Congress on several occasion to reimburse Alabamians who remained loyal to the Union for cattle, corn, hogs, and horses taken by federal troops.

After failing to win renomination against Republican Charles Hinds, Haughey ran as an Independent Republican. The election between him, Hinds, and Democrat William Crawford Sherrod was contentious, particularly between Haughey and Hinds. Haughey found himself the target of various smear campaigns in Alabama newspapers, which sought to paint him as a carpetbagger and question his military service. The dispute reached its peak on July 31, 1869, when a Hinds supporter by the last name of Collins confronted Haughey while he was giving a campaign speech. According to newspaper accounts, the verbal altercation escalated to a fistfight, and then Collins pulled a pistol and shot Haughey. He died five days later and was buried in Green Cemetery near Pinson, Jefferson County. Accounts at the time referred to the shooting as an assassination. Crawford won the election.

Further Reading

- Marion, Nancy E., and Willard M. Oliver. Killing Congress: Assassinations, Attempted Assassinations and Other Violence against Members of Congress. New York: Lexington Books, 2014.