Ross Franklin Gray

Ross Franklin Gray

U.S. Marine Ross Franklin Gray (1920-1945) of Bibb County was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1945 for his bravery while fighting on Iwo Jima during World War II. Gray specialized in clearing mine fields and was lauded for destroying several bunkers with satchels of high explosives while under enemy fire. He was killed in action less than a week later.

Ross Franklin Gray

U.S. Marine Ross Franklin Gray (1920-1945) of Bibb County was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1945 for his bravery while fighting on Iwo Jima during World War II. Gray specialized in clearing mine fields and was lauded for destroying several bunkers with satchels of high explosives while under enemy fire. He was killed in action less than a week later.

Gray was born August 1, 1920, to Benjamin Franklin Gray, a carpenter, and Carrie Clyde Wood Gray in Marvel Valley, Bibb County. It is a small unincorporated community about halfway between West Blocton and Montevallo, Shelby County. He was one of eight siblings who reached adulthood; other siblings may have died at a very young age before his birth. Other brothers also served in the armed forces: Loran Benjamin Gray and John Ray Gray in the U.S. Army and Paul Wood Gray in the U.S. Navy.

Gray attended the local elementary schools of Bibb County and Centerville High School in Centerville, southeast of Marvel Valley, where he played football and basketball. He left school in 1939 before graduating to work for his father. Gray registered for the draft in February 1942 and enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in Birmingham, Jefferson County, that July. Gray trained at Parris Island, South Carolina, the Marine training facility east of the Mississippi River. He was assigned to the Twenty-third Marine Regiment in the Fourth Marine Division, the “Fighting Fourth.” Promoted to private first class in April 1943, Gray was then transferred to Company A, First Battalion of the Twenty-fifth Marine Regiment in the Fourth Division. A devout Protestant who read the Bible daily and sometimes conducted services, he earned the nickname “Deacon” from his comrades and was referred to as “Preacher” in an historical account of the Fifth Amphibious Corp.

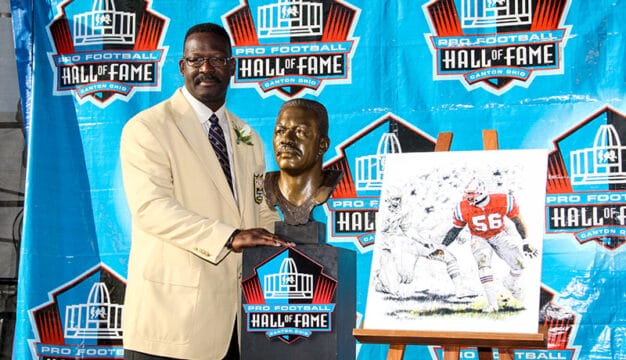

Fallen Marines on Saipan

Gray’s division took part in battles on the island of Kwajalein in late January and early February 1944, Saipan in June and July, and Tinian in July and August, under the overall command of the V Amphibious Force led by Holland M. Smith of Russell County. (Later, Smith would assist with the February 1945 assault on Iwo Jima, but did not lead it owing to personnel conflicts.) The general purpose of these battles was to reduce Japanese defenses that posed a threat to the American naval, land, and airborne forces that were closing in on the Japanese home islands and bringing airborne forces closer to Japan. (Future Alabama governor George C. Wallace served on Tinian aboard B-29 bombers that were targeting Japanese home islands.) These islands had been strongly fortified and were generally well-defended with underground bunkers and difficult-to-attack machine gun, mortar, and artillery installations in concealed positions known as “pill boxes.” In addition, the Japanese defenders were extremely reluctant to surrender and fought with tenacity and fatal fanaticism. Another Alabamian, Eugene Sledge of Mobile, later gained literary fame for his graphic description of the brutality of the Pacific War, though on the islands of Peleliu and Okinawa.

Fallen Marines on Saipan

Gray’s division took part in battles on the island of Kwajalein in late January and early February 1944, Saipan in June and July, and Tinian in July and August, under the overall command of the V Amphibious Force led by Holland M. Smith of Russell County. (Later, Smith would assist with the February 1945 assault on Iwo Jima, but did not lead it owing to personnel conflicts.) The general purpose of these battles was to reduce Japanese defenses that posed a threat to the American naval, land, and airborne forces that were closing in on the Japanese home islands and bringing airborne forces closer to Japan. (Future Alabama governor George C. Wallace served on Tinian aboard B-29 bombers that were targeting Japanese home islands.) These islands had been strongly fortified and were generally well-defended with underground bunkers and difficult-to-attack machine gun, mortar, and artillery installations in concealed positions known as “pill boxes.” In addition, the Japanese defenders were extremely reluctant to surrender and fought with tenacity and fatal fanaticism. Another Alabamian, Eugene Sledge of Mobile, later gained literary fame for his graphic description of the brutality of the Pacific War, though on the islands of Peleliu and Okinawa.

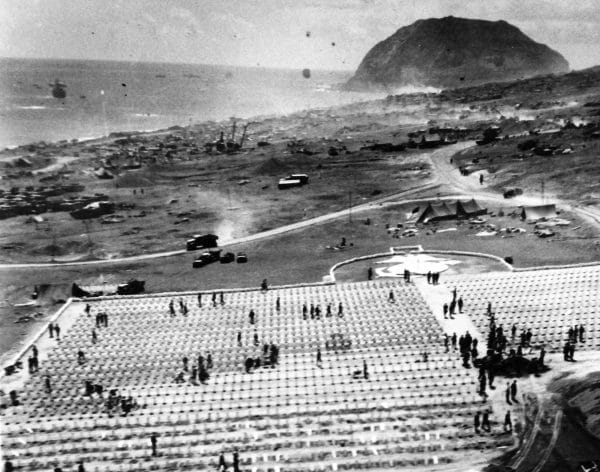

U.S. Marines Invade Iwo Jima

After seeing Saipan fall in July 1944, Japanese commanders on Iwo Jima embarked on a more determined effort to build additional trenches, concrete blockhouses and pill boxes, and caves in the volcanic rock and arm them with machine guns, artillery, mortars, and rockets. Their purpose, according to one Marine Corps account, was to make the island “impregnable.” Just 750 miles or so from Tokyo, Iwo Jima was a Japanese home island, and the Japanese high command also considered it a key feature of its chain of defenses. Japanese military leaders even contemplated completely destroying it instead of allowing it to fall into American hands. Unlike their tactics on the other islands, local Japanese commanders decided not to engage in suicidal banzai charges against American forces, but to dig in and delay.

U.S. Marines Invade Iwo Jima

After seeing Saipan fall in July 1944, Japanese commanders on Iwo Jima embarked on a more determined effort to build additional trenches, concrete blockhouses and pill boxes, and caves in the volcanic rock and arm them with machine guns, artillery, mortars, and rockets. Their purpose, according to one Marine Corps account, was to make the island “impregnable.” Just 750 miles or so from Tokyo, Iwo Jima was a Japanese home island, and the Japanese high command also considered it a key feature of its chain of defenses. Japanese military leaders even contemplated completely destroying it instead of allowing it to fall into American hands. Unlike their tactics on the other islands, local Japanese commanders decided not to engage in suicidal banzai charges against American forces, but to dig in and delay.

Fourth Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima

Gray was promoted to sergeant in August 1944 and trained in numerous specialized operations to lay and neutralize mines and booby traps. Several historical accounts say he was working as a carpenter for the Marines and not in combat because of his religious beliefs. But after his closest friend was killed on Saipan, he grabbed an automatic rifle and went to the front lines. He and his battalion received additional training at Tinian and at sea on the troop transport USS Napa (APA-157) to prepare for the Iwo Jima invasion, known as “Operation Detachment.” They landed on Iwo Jima February 19 as part of the American invasion force. American air forces had begun targeting Iwo Jima defenses with aerial bombs and the Navy had occasionally shelled the island several months prior to the invasion. This activity increased in intensity in the few days leading up to the invasion. Many Japanese defenses, however, remained largely intact. Soon after landing, the Marines encountered sporadic enemy fire; accounts differ as to the severity. Then after the beach and inland areas were crowded with Marines and equipment, the Japanese defenders unleashed their arsenal, much to the surprise of American forces. The Fourth Division in particular, advancing to the northeast of Airfield No. 1, was hard hit by the Japanese counterattack.

Fourth Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima

Gray was promoted to sergeant in August 1944 and trained in numerous specialized operations to lay and neutralize mines and booby traps. Several historical accounts say he was working as a carpenter for the Marines and not in combat because of his religious beliefs. But after his closest friend was killed on Saipan, he grabbed an automatic rifle and went to the front lines. He and his battalion received additional training at Tinian and at sea on the troop transport USS Napa (APA-157) to prepare for the Iwo Jima invasion, known as “Operation Detachment.” They landed on Iwo Jima February 19 as part of the American invasion force. American air forces had begun targeting Iwo Jima defenses with aerial bombs and the Navy had occasionally shelled the island several months prior to the invasion. This activity increased in intensity in the few days leading up to the invasion. Many Japanese defenses, however, remained largely intact. Soon after landing, the Marines encountered sporadic enemy fire; accounts differ as to the severity. Then after the beach and inland areas were crowded with Marines and equipment, the Japanese defenders unleashed their arsenal, much to the surprise of American forces. The Fourth Division in particular, advancing to the northeast of Airfield No. 1, was hard hit by the Japanese counterattack.

Ross Franklin Gray Medal of Honor Ceremony

Gray earned his Medal of Honor two days after the landing, on February 21, near Airfield No. 2. After his lieutenant was killed minutes into the landing, Gray led his platoon. They were in some ravines when Company A was pinned down and encountered an onslaught of hand grenades coming from multiple pill boxes protected by a mine field. He led the platoon back out of immediate danger and returned forward alone to evaluate the situation. While under enemy fire, he cleared a path through the minefield and returned to his unit. Gray then, with three volunteers, acquired 12 satchel charges of high explosives from an ammunition depot. He followed the path he cleared through the mine field and threw a charge into one enemy position to destroy it and retreated to relative safety. Again, although often under machine gun fire, Gray repeated this action a total of eight times to destroy six enemy positions. Afterwards, Grey disarmed the mine field, clearing the way for his regiment to advance. He was killed in action on February 27 by a Japanese shell. The island was declared secure on March 26. Only a few hundred of the 21,000 Japanese defenders were taken prisoner while U.S. forces suffered more than 20,000 wounded and more than 6,800 dead, according to a recent naval history.

Ross Franklin Gray Medal of Honor Ceremony

Gray earned his Medal of Honor two days after the landing, on February 21, near Airfield No. 2. After his lieutenant was killed minutes into the landing, Gray led his platoon. They were in some ravines when Company A was pinned down and encountered an onslaught of hand grenades coming from multiple pill boxes protected by a mine field. He led the platoon back out of immediate danger and returned forward alone to evaluate the situation. While under enemy fire, he cleared a path through the minefield and returned to his unit. Gray then, with three volunteers, acquired 12 satchel charges of high explosives from an ammunition depot. He followed the path he cleared through the mine field and threw a charge into one enemy position to destroy it and retreated to relative safety. Again, although often under machine gun fire, Gray repeated this action a total of eight times to destroy six enemy positions. Afterwards, Grey disarmed the mine field, clearing the way for his regiment to advance. He was killed in action on February 27 by a Japanese shell. The island was declared secure on March 26. Only a few hundred of the 21,000 Japanese defenders were taken prisoner while U.S. forces suffered more than 20,000 wounded and more than 6,800 dead, according to a recent naval history.

USS Gray

On April 16, 1946, at the then-Centerville High School football field, Rear Adm. Aaron S. Merrill of the Eighth Naval District presented Gray’s father with the Medal in a widely attended ceremony that included Gov. Chauncey Sparks. His mother had died some time prior to the award. Gray was exhumed from the Fourth Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima and reburied in Ada Chapel Bible Methodist Church Cemetery in West Blocton. The U.S. Navy fast frigate USS Gray (FF-1054) was named in his honor and served from 1970 until 1991.

USS Gray

On April 16, 1946, at the then-Centerville High School football field, Rear Adm. Aaron S. Merrill of the Eighth Naval District presented Gray’s father with the Medal in a widely attended ceremony that included Gov. Chauncey Sparks. His mother had died some time prior to the award. Gray was exhumed from the Fourth Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima and reburied in Ada Chapel Bible Methodist Church Cemetery in West Blocton. The U.S. Navy fast frigate USS Gray (FF-1054) was named in his honor and served from 1970 until 1991.