Clyde May

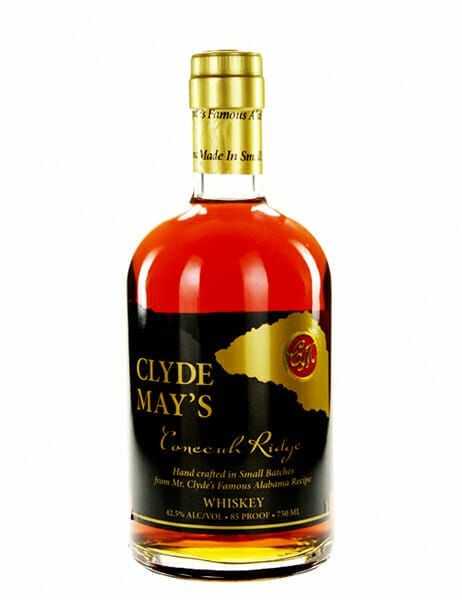

Conecuh Ridge Fine Alabama Whiskey

Lewis Clyde May (1922-1990) is the namesake for Clyde May’s Alabama Whiskey, the official state spirit of Alabama, as designated by the Alabama Legislature in 2004. May was a farmer whose illegal career as a moonshiner had made him an outlaw, and he went to great lengths to keep it a secret. Today, Clyde May’s liquor, formerly known as Conecuh Ridge Alabama Fine Whiskey, is renowned nationwide. In 2012, it was awarded one of the Top 50 Spirits by Wine Enthusiast, as well as a Gold Medal at the MicroLiquor Spirits Awards, and in 2020 was named the official whiskey of the Talladega Superspeedway.

Conecuh Ridge Fine Alabama Whiskey

Lewis Clyde May (1922-1990) is the namesake for Clyde May’s Alabama Whiskey, the official state spirit of Alabama, as designated by the Alabama Legislature in 2004. May was a farmer whose illegal career as a moonshiner had made him an outlaw, and he went to great lengths to keep it a secret. Today, Clyde May’s liquor, formerly known as Conecuh Ridge Alabama Fine Whiskey, is renowned nationwide. In 2012, it was awarded one of the Top 50 Spirits by Wine Enthusiast, as well as a Gold Medal at the MicroLiquor Spirits Awards, and in 2020 was named the official whiskey of the Talladega Superspeedway.

May was born in Bullock County on September 18, 1922, to Annie Lilia May; he never knew his biological father. In November 1928, Annie married Grover Cleveland Marsh, and six months later gave birth to her second son, Charles Dalton Marsh. Six days later, Annie died, and May’s half-brother died shortly afterwards. May was then raised by his grandparents, Charles and Harriet May, and although he was uncle to six nieces and nephews, all seven children were raised as siblings. May’s childhood coincided with the Great Depression, and he was keenly aware of the economic hardships his grandparents faced. Food was scarce, and May sometimes felt guilty for eating food that might have gone to one of his grandparents’ children.

In December 1942 at the age of 21, May enlisted in the U.S. Army at Fort McClellan in Calhoun County. While on leave in April 1943, he married Mary Cynthia Petty, with whom he would have eight children. He fought in World War II, serving in the 77th infantry on both Guam and Okinawa. As he was marching down a hill on Guam, he was wounded in both feet by machine-gun fire and awarded the Purple Heart. During his service, May divided his Army wages between his grandparents and his wife. When he returned to the United States in 1945, May met his first child for the first time. May worked to provide a comfortable life for his wife and children, whom he hoped would never want for anything or feel like a burden as he had.

Despite the unsuitability of Bullock County soil for most types of crops, in 1950 May bought a few hundred acres there and established a farm where he grew mostly peanuts. In the early years, he worked his farm with the help of his sons, but in his later years he also worked for the Bonnie Plant Farm and Baggett Transportation. To supplement his income, Clyde turned to making moonshine, or homemade liquor, the sale of which went unreported to tax authorities, known as revenue agents. The Bullock County terrain provided May with the two most important ingredients: water for the moonshine and shade trees to hide his stills. He took water from natural springs along the Chunnenuggee Ridge, the same springs that flow into the Conecuh River. The other ingredients consisted of yeast, sugar, and rye; May always used whole rye grains and let them ferment naturally. They were imported from the Dakotas because of their bigger grain size compared with the local rye. He considered it a shortcut when his fellow moonshiners chopped up their grains to speed up the fermentation process.

Ever the craftsman, May designed and built his own condenser to cool and concentrate the vapor from the heated rye, water, and sugar into alcohol. He used copper stills and kept his equipment deep in the piney woods near the water source. The shade from the trees shielded the moonshine from the revenue agents, who were always on the lookout for illegal stills. He rarely drank any himself, only when he needed to test the product, as he refused to sell a bad batch. If the batch met his standards, he sold it to bootleggers, who then distributed his product. Moonshining was (and still is) illegal, and though May made illegal moonshine for more than 40 years, he was only arrested once, in 1973 by federal agent Thomas Allison, and convicted. He then served eight months of an 18-month sentence at Maxwell Airforce Base in Montgomery, Montgomery County. He set up his stills again as soon as he was released.

For May and his immediate family, moonshining was a business that they never discussed. They knew it was illegal but considered it an important part of their folk culture, passed down through generations of the May family. The boys carried water to the still, as well as the rye, sugar, bottles, and barrels. The girls cleaned used glass gallon jugs in which May bottled the moonshine. For his special “Christmas Whiskey,” Mary slow-baked Washington State apples that were added to the recipe to mellow out the taste. The Christmas Whiskey was his specialty product, but it took a lot longer to make than conventional moonshine. The formula started off like his regular moonshine, but it was aged in charred oak barrels. Along with Mary’s baked apples, additional charred white oak chips were placed in the barrels with the moonshine during the fall months and aged for at least a year.

May died on January 31, 1990, and was buried in Macedonia Baptist Church Cemetery in Union Springs, Bullock County. His whiskey remains an important part of the Alabama palate. In 1998, Clyde’s son Kenny May started the Conecuh Ridge Distillery, based in Troy, Pike County, as a tribute to his father and began legally making Clyde’s famous Christmas Whiskey. It differs from the original in its use of rye along with corn and malted barley. The whiskey was distilled, however, in Bardstown, Kentucky, using the natural spring water from Conecuh Ridge that was hauled to Kentucky. Kenny named his whiskey “Clyde May’s Conecuh Ridge.”

In March 2004, the Alabama Senate passed a resolution to make Conecuh Ridge Fine Alabama Whiskey the official spirit of Alabama. Gov. Bob Riley objected to the state promoting a commercial product and vetoed the resolution. But the Alabama House and Senate voted to override the governor’s veto. On December 12 of that same year, Kenny was arrested for selling alcohol without a license. This was the result of a year-long investigation by the state Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, which included at least two videotapes of Kenny’s activities.

Among the fallout from this incident, Conecuh Ridge lost the license to sell Alabama’s state spirit in the state of Alabama. Kenny eventually lost the company, and today Clyde May’s Whiskey is distilled in Kentucky and bottled in Florida. The company is headquartered in New York City.

Additional Resources

Hall, Wade. Waters of Life from Conecuh Ridge: The Clyde May Story. Montgomery Ala.: New South Books, 2007.