Jackson's Military Road

Jackson’s Military Road, named for Gen. Andrew Jackson and completed in 1820, was a 516-mile route that connected Nashville, Tennessee, with New Orleans, Louisiana. The U.S. government hoped that the road, which ran through the northwest corner of Alabama, would increase immigration to and economic development in the region, while allowing for the movement of troops during times of conflict in the south. Despite its promise, the Military Road was not significant in Alabama owing to its remoteness along much of its length and lack of funds for upkeep.

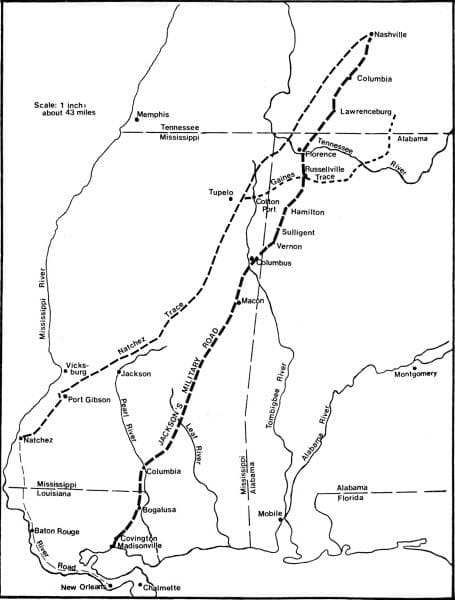

Jackson’s Military Road Map

During the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-14, Jackson and his federal troops travelled across much of what was then known as the Old Southwest, including present-day Alabama, as they fought both the British Army and Native Americans. The region was still largely wilderness, and at the conclusion of the war, Jackson advocated for the construction of a military road connecting Nashville to New Orleans. In 1816, Pres. James Monroe, recognizing the benefits that such a road could have for military purposes, settlement, and economic development, pushed Congress to fund it. On September 16, 1816, Congress appropriated $5,000 to begin construction of the route, dubbed Jackson’s Military Road. The route Jackson advocated ran south from Columbia, Tennessee, to the Tennessee River, and then in a virtually straight line between a point on the Tennessee River west of the Muscle Shoals, Colbert County, and Madisonville, Louisiana (across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans). The mileage of Jackson’s proposed route, at 516 miles, was 208 miles shorter than the existing route from Nashville to New Orleans, which mainly travelled along the Natchez Trace, a long-travelled Native American trail that the U.S. government began using as a post road in 1803.

Jackson’s Military Road Map

During the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-14, Jackson and his federal troops travelled across much of what was then known as the Old Southwest, including present-day Alabama, as they fought both the British Army and Native Americans. The region was still largely wilderness, and at the conclusion of the war, Jackson advocated for the construction of a military road connecting Nashville to New Orleans. In 1816, Pres. James Monroe, recognizing the benefits that such a road could have for military purposes, settlement, and economic development, pushed Congress to fund it. On September 16, 1816, Congress appropriated $5,000 to begin construction of the route, dubbed Jackson’s Military Road. The route Jackson advocated ran south from Columbia, Tennessee, to the Tennessee River, and then in a virtually straight line between a point on the Tennessee River west of the Muscle Shoals, Colbert County, and Madisonville, Louisiana (across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans). The mileage of Jackson’s proposed route, at 516 miles, was 208 miles shorter than the existing route from Nashville to New Orleans, which mainly travelled along the Natchez Trace, a long-travelled Native American trail that the U.S. government began using as a post road in 1803.

The Cherokees and Chickasaws controlled most of the land in Alabama through which the proposed route would travel. Jackson, interested in encouraging white settlement and economic development in the area, entered into negotiations with the two tribes in 1816 to gain control of the land on which the road would be built and also of much of northwest Alabama. In September 1816, Jackson and his commissioners met with the Cherokees and Chickasaws, as well as Choctaw and Creek delegations, near Chickasaw chief George Colbert’s trading post and ferry. By September 20, all of the Native American parties had agreed to land cessions, reserving certain tracts for their own use. As a result of these treaties signed in September 1816 and others in May 1817, much of northwest Alabama was opened for development and settlement.

The survey of the new road began in the fall of 1816, with Maj. William O. Butler charting the first 90 miles south from Colombia, Tennessee, and Capt. Hugh Young surveying the remainder of the route through present-day Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In May 1817, the Eighth Infantry of the Military Division of the South, under the command of Col. Duncan L. Clinch, began construction of the road. An average of 300 men, including blacksmiths, carpenters, and sawyers, worked on the road at any given time. Initial plans called for the road to be 40 feet wide, much wider than the Native American paths that were common through the region. In many places, however, the road had to be narrowed to 25 feet because of the topography. The men rolled the trees they cut down to either side of the road. No effort was made to pull out stumps to ensure a smooth surface; instead, the men cut the trees as near the ground as possible, and using their axes, made the tops of the stumps concave so that they would hold water, thus accelerating decay. In swampy areas, the men constructed bridges or built causeways by laying timber on the road bed and covering it with dirt to raise the level of the surface. By May 1820, the men had completed work on the road, at an estimated cost of $300,000 (including food, wages, and supplies).

The development of the road brought more settlers into Alabama. After a visit to northwest Alabama in 1817, Jackson, his fellow veteran of the Creek War John Coffee, and other investors formed the Cypress Land Company in 1818 to organize settlement in what would become Florence, Lauderdale County. In her observations about Florence in 1821, author Anne Royall noted that travelers and drovers moving horses for sale deeper into the region used the road heavily. The road also helped to open up settlement on the south side of the river, with Tuscumbia becoming an early center of trade as a result of the new route. The road also helped facilitate the growth of Russellville, today the seat of Franklin County, which sat at the crossroads of the Gaines Trace and the Military Road. The road travelled southwest through present-day Hamilton, crossed over the Tombigbee River, and continued on to Columbus, Mississippi.

Despite its promise, many problems prevented the military road from becoming “the most important road in America,” as Jackson initially believed it would be. U.S. control of the Gulf Coast minimized the threat of invasion by a foreign power, and so the military’s use of the road was minimal. Additionally, the lack of money for maintenance also meant that in many areas the road quickly became impassable. Citizens in populated areas of Alabama kept the road clear for their own use, but in less-populated areas, nature quickly reclaimed the roadway. Trees fell and covered bridges and causeways. Floods and other natural disasters destroyed portions of the road. In the end, the U.S. Postal Service never used the route to transport mail, with the Postmaster General reporting that it was in such poor condition that it was useless as a mail route.

The proliferation of steamboats also drew travelers away from the road. In 1821, the year after the military completed construction of the road, the first steamboat travelled up the Mississippi from New Orleans to the Muscle Shoals region on the Tennessee River. Indeed, steamboats would change travel routes throughout the Old Southwest. Travelers increasingly used water routes to move about because they were faster, cheaper, and safer. Steamboats also made trade more profitable, helping Florence and Tuscumbia grow in wealth and population in ways the military road never had.

After Jackson became president in 1829, he made no attempt to improve or conduct routine maintenance of the road, furthering its decline. Today, portions of the road remain visible, with some continuing to be used as modern routes. In Lauderdale County, a stretch of the original road remains in use as the Old Jackson Highway and Hermitage Drive. Across the river, Highway 43 purportedly travels along some of the old highway through Russellville, Hackleburg, and Hamilton.

Further Reading

- Love, William. “General Jackson’s Military Road.” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society 9 (1910): 409.

- Rice, Turner. “Andrew Jackson and His Northwest Alabama Interests.” Journal of Muscle Shoals History 3 (1975): 5.