Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter

The Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter, named for the owners of the adjoining properties on which the structure is located, is an archaeological site in Colbert County that contains evidence of human habitation stretching at least 9,000 years. Despite being heavily looted in the early twentieth century, it still provided evidence of one of the most significant records of Native American prehistory in Alabama, with artifacts and other materials dating from the Paleoindian (~ 15,000 to 9,000 years ago) through the Mississippian periods (1000 to 1550 AD). It was excavated in the 1960s over a three-year period by a team headed by archaeologist David L. DeJarnette of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County.

Northeast Alabama is home to a number of sites containing evidence of habitation by prehistoric humans, with the most famous being Russell Cave, in Jackson County. The Stanfield-Worley site is located along a tributary of Cane Creek in the Tennessee Valley some 150 miles west of Russell Cave, in the Highland Rim Physiographic Section. The shelter site stretches back about 55 feet underneath a massive overhanging rock wall, approximately 250 feet wide, near the creek, providing the Native Americans who used it with protection from the weather and access to fresh water. Most of the people who lived at the shelter over its history were nomadic and did not use it as a permanent residence. Some evidence of use during the Mississippian period has been uncovered at the site, and although Mississippian peoples were more sedentary rather than nomadic, they still likely used the site as a hunting camp or other temporary shelter.

Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter

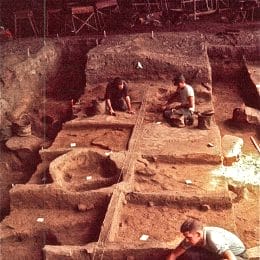

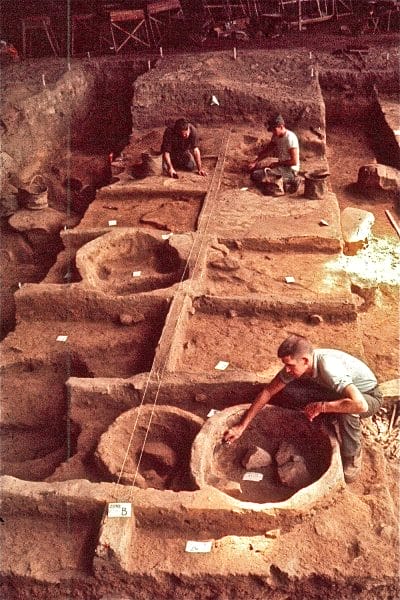

Evidence of prehistoric human habitation at the shelter was reported in early 1960 by landowner C. H. Worley to archaeologists at the University of Alabama. DeJarnette conducted some test excavations and then in 1962 led what would be a three-year project at the site, after gaining the permission of Robert B. Stanfield, who owned the land that adjoined Worley’s property. The Archaeological Research Association of Alabama (ARSA) funded the work, and members of the Alabama Archaeological Society (AAS) provided much of the labor and analysis. Excavations involved removing of up to five feet of naturally accumulated soil mixed with debris from food preparation and fires. In all, archaeologists uncovered four distinct layers. The deepest and oldest layer, designated Zone D, was determined to have been laid down at least 9,500 years ago, in the late Paleoindian period, which marks the very end of the last Ice Age. Artifacts recovered from this layer include lance-shaped triangular stone projectile points made by people that archaeologists have named the Dalton culture, and side-notched projectile points, from the later Big Sandy Culture. Many of these points show evidence of repeated resharpening, indicating that people were reusing their tools and probably lived a nomadic lifestyle. Excavations revealed distinct cutting and scraping tools and large flat stones, known as anvils, discovered underneath the oldest soil layer in Zone D. This type of worked stone provides the earliest evidence in Alabama that Native Americans were creating tools to crack nuts for food. Abundant bones of deer, squirrel, raccoon, and other animals preserved in the soil indicate that Native Americans hunted them for food. A layer of clean sand with no artifacts, designated Zone C, accumulated on top of Zone D and sealed it off from the layers above, so archaeologists know that all the artifacts found in Zone D were used by the people inhabiting the shelter at that very earliest time.

Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter

Evidence of prehistoric human habitation at the shelter was reported in early 1960 by landowner C. H. Worley to archaeologists at the University of Alabama. DeJarnette conducted some test excavations and then in 1962 led what would be a three-year project at the site, after gaining the permission of Robert B. Stanfield, who owned the land that adjoined Worley’s property. The Archaeological Research Association of Alabama (ARSA) funded the work, and members of the Alabama Archaeological Society (AAS) provided much of the labor and analysis. Excavations involved removing of up to five feet of naturally accumulated soil mixed with debris from food preparation and fires. In all, archaeologists uncovered four distinct layers. The deepest and oldest layer, designated Zone D, was determined to have been laid down at least 9,500 years ago, in the late Paleoindian period, which marks the very end of the last Ice Age. Artifacts recovered from this layer include lance-shaped triangular stone projectile points made by people that archaeologists have named the Dalton culture, and side-notched projectile points, from the later Big Sandy Culture. Many of these points show evidence of repeated resharpening, indicating that people were reusing their tools and probably lived a nomadic lifestyle. Excavations revealed distinct cutting and scraping tools and large flat stones, known as anvils, discovered underneath the oldest soil layer in Zone D. This type of worked stone provides the earliest evidence in Alabama that Native Americans were creating tools to crack nuts for food. Abundant bones of deer, squirrel, raccoon, and other animals preserved in the soil indicate that Native Americans hunted them for food. A layer of clean sand with no artifacts, designated Zone C, accumulated on top of Zone D and sealed it off from the layers above, so archaeologists know that all the artifacts found in Zone D were used by the people inhabiting the shelter at that very earliest time.

Bone and Antler Tools

Zone B, located above the layer of clean sand, contained debris and artifacts that mostly date to the Middle Archaic period, sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 BCE. During this time, the shelter was used as a burial site as well as a residence. Of the 11 graves found at the site, at least six dated to the Middle Archaic, with the rest dating to later periods of occupation. Some of the people were buried with tools that likely were viewed as useful to the departed in the afterlife. Because the tools were all assembled and buried together at the same time in a grave, archaeologists can tell much about what sort of tools were being used during that period.

Bone and Antler Tools

Zone B, located above the layer of clean sand, contained debris and artifacts that mostly date to the Middle Archaic period, sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 BCE. During this time, the shelter was used as a burial site as well as a residence. Of the 11 graves found at the site, at least six dated to the Middle Archaic, with the rest dating to later periods of occupation. Some of the people were buried with tools that likely were viewed as useful to the departed in the afterlife. Because the tools were all assembled and buried together at the same time in a grave, archaeologists can tell much about what sort of tools were being used during that period.

The uppermost soil layer, Zone A, produced artifacts from a broad period of time, ranging from from the Woodland period (~ 3,000 to 1,000 years ago) to the Mississippian period. Most of the artifacts in this upper zone had been disturbed from their original context, but materials buried in storage pits dug into lower layers during those times were preserved in place. The lower sections of Zone A produced significant amounts of Woodland pottery and projectile points, indicating longer residency by the Native Americans at that time. Mississippian artifacts were almost all projectile points, suggesting that the site was used almost exclusively as a hunting camp.

Archaeologists from UA and AAS analyzed materials from the excavations and established a projectile point typology that spans thousands of years. This typology is still used by archaeologists to date many other archaeological sites that contain projectile points. The typology, along with analysis of pottery, animal bones, other stone and bone tools, and radiocarbon dates, was published in AAS’s Journal of Alabama Archaeology in 1962. Much of the material excavated, stored at the Walter B. Jones Archaeological Museum at Moundville Archaeological Park, has not been analyzed, leaving much still to be learned about the people who inhabited the Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter.

Further Reading

- DeJarnette, David L., Edward B. Kurjack, and James W. Cambron. “Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter Excavations.” Journal of Alabama Archaeology 8 (December 1962): 1-124.

- Futato, Eugene M. “A Synopsis of Paleoindian and Early Archaic Research in Alabama.” In The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1996.

- ———. “The North Alabama Project: An AAS Excavation Scrapbook.” Journal of Alabama Archaeology 50 (December 2004): 71-137.