Camp Sheridan

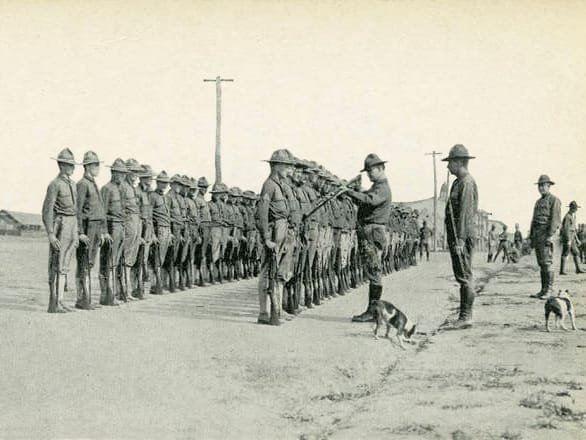

Inspection at Camp Sheridan

Camp Sheridan was a U.S. Army training facility located in Montgomery, Montgomery County, during World War I. It was situated on 4,000 acres of land approximately three miles northeast of downtown Montgomery along the Lower Wetumpka Road. It was one of several camps the federal government established in Alabama to prepare U.S. soldiers and airmen for World War I, the most notable being Camp McClellan along with Taylor Field off of Pike Road in Montgomery and Aviation Engine and Repair Depot No. 3 at Wright Field, later known as Maxwell Air Force Base. Servicemen also trained at Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan.

Inspection at Camp Sheridan

Camp Sheridan was a U.S. Army training facility located in Montgomery, Montgomery County, during World War I. It was situated on 4,000 acres of land approximately three miles northeast of downtown Montgomery along the Lower Wetumpka Road. It was one of several camps the federal government established in Alabama to prepare U.S. soldiers and airmen for World War I, the most notable being Camp McClellan along with Taylor Field off of Pike Road in Montgomery and Aviation Engine and Repair Depot No. 3 at Wright Field, later known as Maxwell Air Force Base. Servicemen also trained at Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan.

After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Montgomery city officials lobbied hard to receive one of 3,000 planned military bases. Stanley Dent, chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs and congressman from Alabama’s Second District, added leverage to Montgomery’s bid. On June 25, 1917, the city proposed to the War Department that it would provide 2,000 acres rent free, water service of two million gallons per day, 200 kilowatts of electricity per day as well as poles and wires, and up to 25 million feet of lumber at low prices. Gen. Leonard Wood recommended Montgomery’s bid to the War Department, and construction began on July 23.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Named for Gen. Phil Sheridan, a Union cavalry commander during the Civil War, the camp was the training ground for the 30,000 men of Ohio’s 37th Infantry “Buckeye” Division who arrived between August and October 1917 and then embarked for France in June 1918. The 9th Infantry Division replaced the 37th and was mustered into service in July. It transferred to Camp Mills, New York, in October 1918 but returned in December; the men remained at Camp Sheridan until their unit was decommissioned in February 1919. Interestingly, noted Jazz-Age author F. Scott Fitzgerald was a lieutenant in the 9th and met his future wife, Zelda Sayre, while stationed at Camp Sheridan.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Named for Gen. Phil Sheridan, a Union cavalry commander during the Civil War, the camp was the training ground for the 30,000 men of Ohio’s 37th Infantry “Buckeye” Division who arrived between August and October 1917 and then embarked for France in June 1918. The 9th Infantry Division replaced the 37th and was mustered into service in July. It transferred to Camp Mills, New York, in October 1918 but returned in December; the men remained at Camp Sheridan until their unit was decommissioned in February 1919. Interestingly, noted Jazz-Age author F. Scott Fitzgerald was a lieutenant in the 9th and met his future wife, Zelda Sayre, while stationed at Camp Sheridan.

The camp’s approximate boundaries were Jackson Ferry Road to the west, Pickett’s Spring (home of Alabama historian Albert J. Pickett), then the Western of Alabama Railroad tracks to the north, the Central of Georgia railroad tracks to the south, and the small creek that now bounds Gunter Air Force Base to the east. Within camp boundaries were the village of Chisholm (that was later subsumed by the city) as well as Vandiver Park, site of the Alabama State Fair after 1902, mustering ground for the Fourth Alabama Militia, and the August 1917 mobilization point of the 167th Infantry Regiment, as the Fourth was later designated.

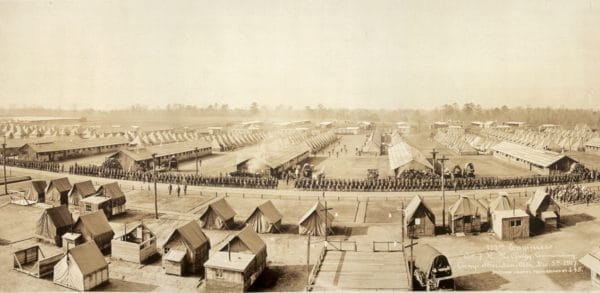

The Montgomery-based Algernon Blair Company erected almost all of the camp’s wooden structures: 313 mess halls, 314 bath houses and latrines, 40 warehouses, a hospital, a post office, a library, a gymnasium, and the headquarters building at Pickett’s Spring. The soldiers lived in 4,000 wood-floored tents. Local citizens had hoped the War Department would erect a permanent camp, called a cantonment, but they were nevertheless excited about the financial boon brought by the temporary camp. Construction cost more than $1.5 million, and the payroll and supply purchases of the 30,000 men of the 37th totaled almost $1.4 million per month. City officials, other civic leaders, and those hoping to make a profit anticipated that many soldiers would bring their families as well and looked forward to the influx of possible home renters and shoppers. Indeed, local officials reportedly muted their concerns at naming the camp after a former Union general given the amount of money the War Department was spending on the facility.

Camp Sheridan Division Headquarters

Other facilities arose in the area in support of the camp activities. Rifle and artillery ranges almost the size of the camp itself were established 12 miles away on the Tallapoosa River. Three miles from camp on the Central of Georgia Railroad tracks was Remount Depot 312, where 300 veterinary officers and soldiers cared for more than 17,000 horses and mules. That facility consisted of corrals for 5,000 animals, feed lots, barns, veterinary hospitals, blacksmith shops, and living quarters on 160 acres. African American troops at the Depot stayed in segregated barracks and trained in segregated units. Although not directly associated with Camp Sheridan, Taylor Field, on what is now Pike Road, hosted 100 cadets training as pilots in the spring and summer of 1918. Their repair shops, Aviation Engine and Repair Depot No. 3, occupied the Wright Brothers’ field in western Montgomery, now the site of Maxwell Air Force Base.

Camp Sheridan Division Headquarters

Other facilities arose in the area in support of the camp activities. Rifle and artillery ranges almost the size of the camp itself were established 12 miles away on the Tallapoosa River. Three miles from camp on the Central of Georgia Railroad tracks was Remount Depot 312, where 300 veterinary officers and soldiers cared for more than 17,000 horses and mules. That facility consisted of corrals for 5,000 animals, feed lots, barns, veterinary hospitals, blacksmith shops, and living quarters on 160 acres. African American troops at the Depot stayed in segregated barracks and trained in segregated units. Although not directly associated with Camp Sheridan, Taylor Field, on what is now Pike Road, hosted 100 cadets training as pilots in the spring and summer of 1918. Their repair shops, Aviation Engine and Repair Depot No. 3, occupied the Wright Brothers’ field in western Montgomery, now the site of Maxwell Air Force Base.

Montgomery welcomed the soldiers, and local residents organized themselves to accommodate the newcomers. The Knights of Columbus and Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) built facilities at the camp to entertain the troops, the Red Cross provided social services, and the local branch of the War Camp Community Service coordinated churches, clubs, and other groups to aid the men. The Montgomery Chamber of Commerce organized committees to suppress vice and enforce prohibition, provide recreation and transportation, and promote religious participation. The Women’s Central Committee, composed of representatives from the women’s club movement, service clubs, and church groups, prepared to host established procedures to welcome individual visitors and tour groups from the soldiers’ hometowns and to provide “wholesome” social alternatives to vice. Members of the Women’s Motor Service used their personal, and rare, automobiles to transport soldiers between camp and town before Montgomery Traction and Light Company installed streetcar service to Camp Sheridan.

Mess Hall at Camp Sheridan

Officers at Camp Sheridan strove to keep the men healthy. Doctors established a sanitary zone extending five miles beyond the camp in all directions in which they eradicated mosquitos and flies. When sexually transmitted diseases became a problem, camp commanders restricted soldiers from some areas and city officials closed houses of prostitution. In May 1918, the War Department signed a sewerage system contract with Algernon Blair, but it remained unfinished when the war ended. Regardless of precautions, the camp was unprepared for the flu pandemic that fall, which killed thousands of Alabamians and millions around the world. Hundreds of soldiers at Camp Sheridan became ill, and dozens died in the fall of 1918 before the disease burned itself out.

Mess Hall at Camp Sheridan

Officers at Camp Sheridan strove to keep the men healthy. Doctors established a sanitary zone extending five miles beyond the camp in all directions in which they eradicated mosquitos and flies. When sexually transmitted diseases became a problem, camp commanders restricted soldiers from some areas and city officials closed houses of prostitution. In May 1918, the War Department signed a sewerage system contract with Algernon Blair, but it remained unfinished when the war ended. Regardless of precautions, the camp was unprepared for the flu pandemic that fall, which killed thousands of Alabamians and millions around the world. Hundreds of soldiers at Camp Sheridan became ill, and dozens died in the fall of 1918 before the disease burned itself out.

After the war ended in November 1918, the United States quickly reduced its military strength and converted Camp Sheridan into a demobilization center. The city of Montgomery paid the federal government $10,000 for the land leases and eventually acquired the land from its original owners. Although F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in his 1928 short story, “The Last of the Belles,” that the camp had reverted to cotton fields, during the 1920s, the Alabama Highway Department stored war surplus highway construction equipment in the city-owned warehouses left by the Army. Eventually, residential neighborhoods, the Montgomery Zoo, the Alabama Department of Transportation, and businesses incorporated Camp Sheridan into the city. Montgomery’s Boylston neighborhood, which now sits where division headquarters stood, hosts a commemorative display on Johnson Avenue.

Further Reading

- May, E. L. Souvenir History of Camp Sheridan, Montgomery, Alabama. Montgomery: N.p., 1918.

- Olliff, Martin T., ed. The Great War in the Heart of Dixie: Alabama in World War I. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.