Battle of Spanish Fort

Spanish Fort was part of the Confederate fortifications guarding the eastern approaches to Mobile during the Civil War and was captured by federal forces on April 8, 1865. The federal siege and capture of Spanish Fort and nearby Fort Blakeley on the following day led to the surrender of the city of Mobile, Mobile County, in the last days of the Civil War. During the colonial era, a French trading post, constructed in 1712, and a Spanish fort, built in 1780, occupied the site of the Confederate fortifications.

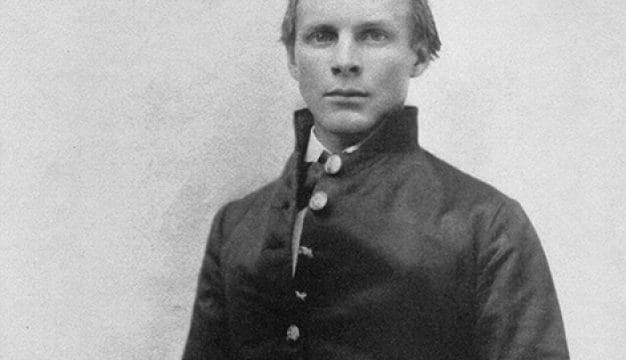

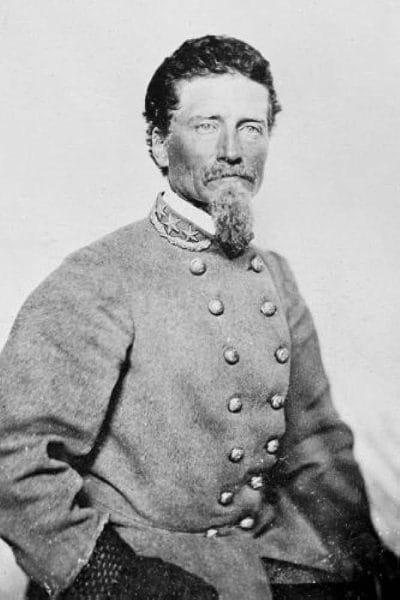

Dabney H. Maury

By 1864, Maj. Gen. Dabney H. Maury, Confederate commander of the Mobile garrison, had constructed fortifications to protect the city’s western approach, with water approaches being defended by a series of underwater obstructions and island-based artillery batteries. To protect the city’s eastern approaches, Brig. Gen. Danville Ledbetter constructed a series of earthen fortifications, including Spanish Fort, directly across the upper bay from Mobile on the bluffs above the Blakeley River in Baldwin County. Fort Blakeley, some eight miles north of Spanish Fort, protected the city on the northeast. By early 1865, Mobile’s garrison numbered almost 10,000 troops.

Dabney H. Maury

By 1864, Maj. Gen. Dabney H. Maury, Confederate commander of the Mobile garrison, had constructed fortifications to protect the city’s western approach, with water approaches being defended by a series of underwater obstructions and island-based artillery batteries. To protect the city’s eastern approaches, Brig. Gen. Danville Ledbetter constructed a series of earthen fortifications, including Spanish Fort, directly across the upper bay from Mobile on the bluffs above the Blakeley River in Baldwin County. Fort Blakeley, some eight miles north of Spanish Fort, protected the city on the northeast. By early 1865, Mobile’s garrison numbered almost 10,000 troops.

U.S. Navy rear admiral David G. Farragut’s victory in the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864, essentially closed the port. But because federal forces were heavily engaged elsewhere, especially in the siege of Atlanta, Georgia, Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby, commander of the Military Division of West Mississippi, had insufficient manpower to capture Mobile. By early 1865, however, Canby began acquiring the forces necessary to capture Mobile by first taking Spanish Fort.

Defenses

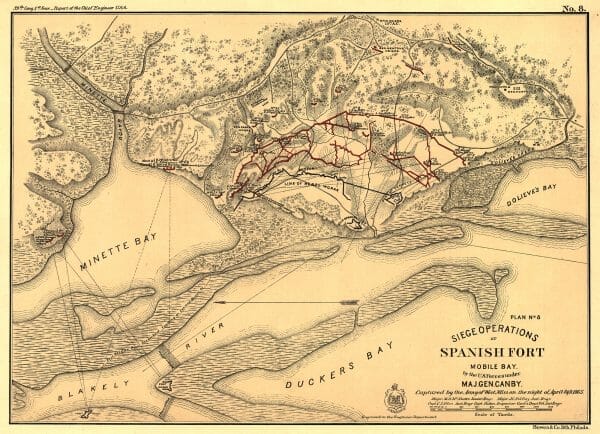

Battle of Spanish Fort Map

The fort sat on a high hill with a large flat top, running north-south, and had steep sides and easy access to the bay by way of the Blakeley River, giving the site a 360-degree view of the surrounding terrain. The Confederates had constructed trenches and artillery redoubts in a semi-circle two miles long and 1,000 yards wide between Minette Bay and D’Olive Bay. Fort McDermott, positioned at the southern end of the hilltop, guarded the land approaches, and Old Spanish Fort, the site of the original Spanish fort located at the north end of the hill, covered the river approaches. The Confederate defenses consisted of six Louisiana infantry regiments, commanded by Brig. Gen. Randall L. Gibson and five Alabama infantry regiments, commanded by Brig. Gen. James T. Holtzclaw. The forces were equipped with 47 pieces of artillery, but 14 were pointed toward the bay to defend against an attack from that direction. The Confederates had largely left the northern end of the defenses unfortified because swamps and a high water table made construction difficult.

Battle of Spanish Fort Map

The fort sat on a high hill with a large flat top, running north-south, and had steep sides and easy access to the bay by way of the Blakeley River, giving the site a 360-degree view of the surrounding terrain. The Confederates had constructed trenches and artillery redoubts in a semi-circle two miles long and 1,000 yards wide between Minette Bay and D’Olive Bay. Fort McDermott, positioned at the southern end of the hilltop, guarded the land approaches, and Old Spanish Fort, the site of the original Spanish fort located at the north end of the hill, covered the river approaches. The Confederate defenses consisted of six Louisiana infantry regiments, commanded by Brig. Gen. Randall L. Gibson and five Alabama infantry regiments, commanded by Brig. Gen. James T. Holtzclaw. The forces were equipped with 47 pieces of artillery, but 14 were pointed toward the bay to defend against an attack from that direction. The Confederates had largely left the northern end of the defenses unfortified because swamps and a high water table made construction difficult.

In early January, Canby began massing forces to capture Spanish Fort. On March 17, a total of 32,000 troops of XII Corps and XVI Corps, Army of West Mississippi, began moving by steamboats from Fort Gaines and over land from Fort Morgan to a staging area on the Fish River, 20 miles south of Spanish Fort. Simultaneously, about 13,000 federal soldiers began marching north and west from Pensacola to cut off the railroad between Mobile and Montgomery and then seize Blakeley. By March 24, Canby’s forces had arrived at the Fish River and began marching north toward Spanish Fort the next day. Within three days, there were thousands of federal soldiers in the vicinity of the Confederate fortifications, into which Confederate troops, numbering about 3,000 men, withdrew.

Federal Advance and Attack

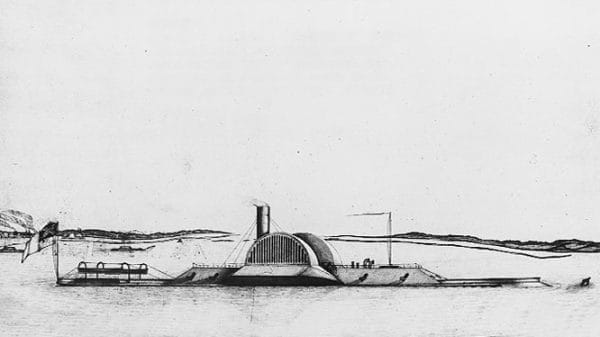

CSS Nashville

U.S. forces began their advance on March 27, came under fire, and encircled the land approaches to Spanish Fort along a three-mile front about a half mile from the Confederate lines by sunset. Realizing that a full frontal assault on the fort would probably result in heavy casualties, Canby decided to dig successive trenches parallel to the Confederate line of fortifications and rifle pits to close the distance to the Confederate fortifications while keeping his troops safe from attack. Confederate sharpshooters and artillery fire regularly harassed the federal sappers, or engineers, and sharpshooters fired back to protect the diggers. Ebenezer Farrand, commander of the Confederate naval squadron in Mobile Bay, moved the armored gunboats CSS Huntsville, CSS Nashville, and CSS Morgan up the Tensaw River, midway between Spanish Fort and Blakeley to aid the two Confederate garrisons by shelling the federal troops. They did so for several days until they ran out of ammunition.

CSS Nashville

U.S. forces began their advance on March 27, came under fire, and encircled the land approaches to Spanish Fort along a three-mile front about a half mile from the Confederate lines by sunset. Realizing that a full frontal assault on the fort would probably result in heavy casualties, Canby decided to dig successive trenches parallel to the Confederate line of fortifications and rifle pits to close the distance to the Confederate fortifications while keeping his troops safe from attack. Confederate sharpshooters and artillery fire regularly harassed the federal sappers, or engineers, and sharpshooters fired back to protect the diggers. Ebenezer Farrand, commander of the Confederate naval squadron in Mobile Bay, moved the armored gunboats CSS Huntsville, CSS Nashville, and CSS Morgan up the Tensaw River, midway between Spanish Fort and Blakeley to aid the two Confederate garrisons by shelling the federal troops. They did so for several days until they ran out of ammunition.

By April 8, the sappers had established defensive positions immediately in front of the Confederate fortifications. Canby had positioned 90 guns to fire on the Confederates, who had only 30 or so guns. U.S. and Confederate artillery traded fire throughout the day, covering the battlefield with flame and smoke and shaking the ground for miles around. Around 5:00 p.m., the 8th Iowa Infantry Regiment, led by Col. James Geddes, broke into the weak northern part of the battlefield and entered the fort’s first line of breastworks. By dusk, Gibson realized he could not withstand a continued federal attack and evacuated the fort. The Confederates spiked their guns, destroyed the gun carriages, and withdrew to the nearby island battery of Fort Huger. Many made their way to Mobile by boat, and Gibson sent approximately 1,000 troops to Blakeley. About midnight, federal forces realized that the vast majority of the Confederates had left the fort. Canby’s men captured about 500 prisoners and large quantities of artillery shells and gunpowder. Estimated casualties from the battle were 657 U.S. soldiers and 744 Confederates.

Confederates Fall

After transferring men to the fortifications east of Mobile during the respective sieges, Gen. Maury now had only about 4,500 men left and began evacuating the city on the evening of April 11. Meanwhile, Mobile mayor Robert H. Slough surrendered the city without a fight on April 12, 1865, three days after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Maury surrendered his forces to Gen. Canby at Citronelle, Mobile County, on May 4, 1865.

The Spanish Fort battlefield is located north of present day U. S. Highway 31 and west of State Highway 225. Its waterfront location made it attractive for development, and, as a result, housing developments now cover most of the original battlefield. But visitors to the area can still see traces of the original earthworks and trenches in the yards of homes and an overgrown section of Fort (Battery) McDermott along the city of Spanish Fort‘s Main Street. The state of Alabama has erected historical markers at several points on the battlefield.

Further Reading

- Hearn, Chester G. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1993.

- O’Brien, Sean Michael. Mobile 1865: Last Stand of the Confederacy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2001.

- Waugh, John C., and Grady McWhiney. Last Stand at Mobile. Abilene, Kan.: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2002.