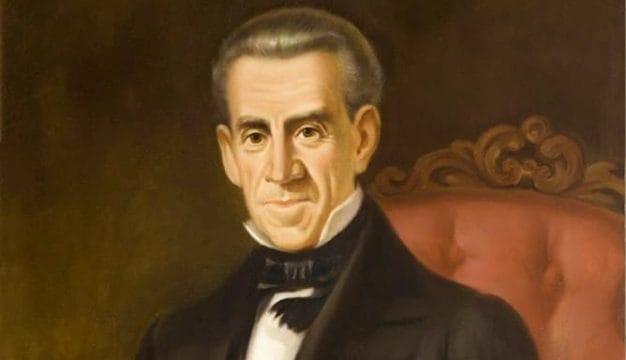

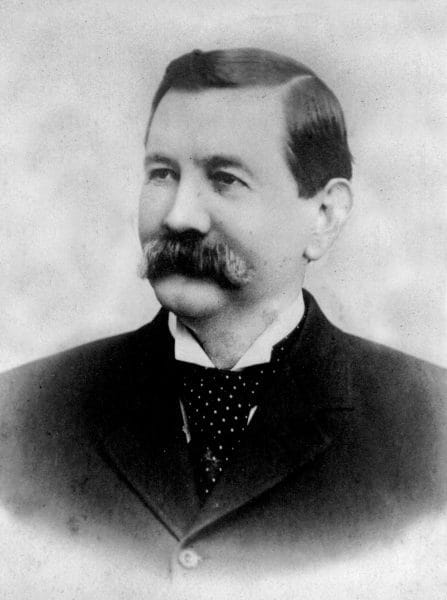

Henry DeBardeleben

Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben (1840-1910), along with father-in-law Daniel Pratt, Truman Aldrich, and James W. Sloss, was one of the most important of Alabama’s early industrialists. He was an avid deal-maker, promoting and marketing his products and ideas to anyone who would listen and experiencing both boom and bust in the state’s extraction industries in the late nineteenth century. Many historians considered him a quintessential New South industrialist, and he was instrumental in developing coal and iron interests in north-central Alabama.

Henry DeBardeleben

DeBardeleben was born July 22, 1840, in Autauga County to cotton planter Henry DeBardelaben, who moved to Alabama from South Carolina, and Mary Anne Fairchild; he had two siblings and eight half siblings from his father’s previous marriage to Nancy Ann Fralich. DeBardeleben was orphaned at age 10 and became the legal ward of cotton-gin manufacturer Daniel Pratt. At the beginning of the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the Prattville Dragoons, fighting under Confederate general Braxton Bragg’s command at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862. DeBardeleben continued to serve in the Confederate Army until the following year, when Gov. John Gill Shorter appointed him to manage a bobbin factory owned by Pratt that had been pressed into service by the Confederate government. He married Daniel Pratt’s daughter Ellen later that year, and the couple eventually inherited Daniel Pratt’s wealth. They would have eight children.

Henry DeBardeleben

DeBardeleben was born July 22, 1840, in Autauga County to cotton planter Henry DeBardelaben, who moved to Alabama from South Carolina, and Mary Anne Fairchild; he had two siblings and eight half siblings from his father’s previous marriage to Nancy Ann Fralich. DeBardeleben was orphaned at age 10 and became the legal ward of cotton-gin manufacturer Daniel Pratt. At the beginning of the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the Prattville Dragoons, fighting under Confederate general Braxton Bragg’s command at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862. DeBardeleben continued to serve in the Confederate Army until the following year, when Gov. John Gill Shorter appointed him to manage a bobbin factory owned by Pratt that had been pressed into service by the Confederate government. He married Daniel Pratt’s daughter Ellen later that year, and the couple eventually inherited Daniel Pratt’s wealth. They would have eight children.

In 1872, DeBardeleben formed a partnership with his father-in-law to purchase a majority of the Red Mountain Iron and Coal Company. Changing the name to the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company, they rebuilt the Oxmoor furnaces in Jefferson County, which had been destroyed in 1865 by U.S. cavalry under the command of Gen. James H. Wilson. It went into blast the following year. The economic Panic of 1873 and Pratt’s death that same year curtailed the endeavor, however, but other capitalists succeeded in producing pig iron at Oxmoor in 1876.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

DeBardeleben formed a partnership with Truman H. Aldrich and James W. Sloss in 1877 to develop the Birmingham District. They opened slope and shaft mines at Pratt City, tapping the Pratt (formerly Browne) Seam, and founded the Pratt Coal and Coke Company in January 1878 with DeBardeleben as president. The triumvirate constructed railroad lines from mines used exclusively for the company’s own purposes, known as captive mines, in Pratt City (which was later annexed to Birmingham, Jefferson County, in 1910) to the iron furnaces in Birmingham, and shipped their first coal one year later. Both Aldrich and Sloss had left the company by 1881, but Debardeleben continued to promote coal and iron production. He invested in coal mines, coke ovens, blast furnaces, iron works, and rolling mills, and he travelled extensively to find buyers and to develop markets. His Alice Furnace (named for his first-born daughter who died in infancy) went into blast in November 1880, marking the first use of coke in producing pig iron.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

DeBardeleben formed a partnership with Truman H. Aldrich and James W. Sloss in 1877 to develop the Birmingham District. They opened slope and shaft mines at Pratt City, tapping the Pratt (formerly Browne) Seam, and founded the Pratt Coal and Coke Company in January 1878 with DeBardeleben as president. The triumvirate constructed railroad lines from mines used exclusively for the company’s own purposes, known as captive mines, in Pratt City (which was later annexed to Birmingham, Jefferson County, in 1910) to the iron furnaces in Birmingham, and shipped their first coal one year later. Both Aldrich and Sloss had left the company by 1881, but Debardeleben continued to promote coal and iron production. He invested in coal mines, coke ovens, blast furnaces, iron works, and rolling mills, and he travelled extensively to find buyers and to develop markets. His Alice Furnace (named for his first-born daughter who died in infancy) went into blast in November 1880, marking the first use of coke in producing pig iron.

Alabama Great Southern Railway Depot

DeBardeleben sold the Pratt Coal and Coke Company to Enoch Ensley in 1881 after suffering health problems. Exhibiting symptoms of tuberculosis, he sought the dry climate of Laredo, Texas, and northern Mexico, where he engaged in sheep ranching. He experienced a rapid recovery and returned to Birmingham in 1882, partnering with Kentucky lawyer William Thompson Underwood to build the Mary Pratt Furnace, named for his third-born child. The operation went into blast in 1883, but DeBardeleben soon returned to Texas after suffering a relapse of tuberculosis. Two years later, he left Laredo for Birmingham, and he and banker David Roberts of Charleston, South Carolina, sold shares to financiers to raise funds and capitalize the DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company (DCIC) at $2 million. The DCIC developed coal and iron mines, coke ovens, and blast furnaces, eventually increasing its capitalization to $13 million. The partners also founded the Bessemer Land and Improvement Company to sell real estate and to promote the growth of Bessemer in Jefferson County. Located 13 miles southwest of Birmingham, DeBardeleben’s new steel-making town encompassed 150,000 acres at the gateway to the Warrior and Cahaba coal fields. Named for English steel tycoon Sir Henry Bessemer, the city never realized its potential in rivaling the ironworks of Birmingham.

Alabama Great Southern Railway Depot

DeBardeleben sold the Pratt Coal and Coke Company to Enoch Ensley in 1881 after suffering health problems. Exhibiting symptoms of tuberculosis, he sought the dry climate of Laredo, Texas, and northern Mexico, where he engaged in sheep ranching. He experienced a rapid recovery and returned to Birmingham in 1882, partnering with Kentucky lawyer William Thompson Underwood to build the Mary Pratt Furnace, named for his third-born child. The operation went into blast in 1883, but DeBardeleben soon returned to Texas after suffering a relapse of tuberculosis. Two years later, he left Laredo for Birmingham, and he and banker David Roberts of Charleston, South Carolina, sold shares to financiers to raise funds and capitalize the DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company (DCIC) at $2 million. The DCIC developed coal and iron mines, coke ovens, and blast furnaces, eventually increasing its capitalization to $13 million. The partners also founded the Bessemer Land and Improvement Company to sell real estate and to promote the growth of Bessemer in Jefferson County. Located 13 miles southwest of Birmingham, DeBardeleben’s new steel-making town encompassed 150,000 acres at the gateway to the Warrior and Cahaba coal fields. Named for English steel tycoon Sir Henry Bessemer, the city never realized its potential in rivaling the ironworks of Birmingham.

After consolidating his Bessemer interests with the Henry Ellen Coal Company and the Eureka Company, DeBardeleben sold the DCIC to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI) of Chattanooga in 1891. He became first vice president the following year and immediately attempted to manipulate the company’s stock prices. His attempts were ill-timed, however. He lost his fortune and was forced to resign in the wake of the economic Panic of 1893. At that juncture, he organized the Alabama Fuel and Iron Company based in St. Clair County. Developing mining operations in that county at Acmar and Margaret and in Acton, Shelby County, and in Overton, Jefferson County, he established an industrial legacy for his son, Charles F. DeBardeleben.

Although DeBardeleben was involved in breaking the Great Strike of 1894 among coal miners and had used convict labor in several mining operations, he, along with Aldrich and Sloss, left his mark as one of the most important industrialists in Alabama. He died on December 6, 1910, and is interred in Birmingham’s Oak Hill Cemetery.

Additional Resources

Armes, Ethel. The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama. Birmingham: Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, 1910.

Day, James Sanders. Diamonds in the Rough: A History of Alabama’s Cahaba Coal Field. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013.

Fuller, Justin. “Henry F. DeBardeleben, Industrialist of the New South.” Alabama Review 34 (January 1986): 3-18.

Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.