New Deal in Alabama

Skyline Farms Band, 1937

The “New Deal” is the name given to the program of socioeconomic reforms initiated by Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democrat-controlled Congress, and other federal and state leaders in response to the Great Depression. In Alabama, the New Deal consisted of numerous programs aimed toward revitalizing the depressed economy, providing relief for the poor, employing men and women on public works projects, and preserving the natural environment and folk culture. Although the New Deal did not end the Depression, it did profoundly affect life in Alabama by providing much-needed economic assistance, instituting governmental protections for farmers and workers, advancing the diversification of the state economy, and encouraging a more Progressive outlook in state politics.

Skyline Farms Band, 1937

The “New Deal” is the name given to the program of socioeconomic reforms initiated by Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democrat-controlled Congress, and other federal and state leaders in response to the Great Depression. In Alabama, the New Deal consisted of numerous programs aimed toward revitalizing the depressed economy, providing relief for the poor, employing men and women on public works projects, and preserving the natural environment and folk culture. Although the New Deal did not end the Depression, it did profoundly affect life in Alabama by providing much-needed economic assistance, instituting governmental protections for farmers and workers, advancing the diversification of the state economy, and encouraging a more Progressive outlook in state politics.

Addressing Unemployment

The most widely known New Deal programs were those designed to provide employment for young men, both white and African American, so that they would be able to send money home to help support their families. The most famous program was the 1933 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed young men in segregated units on public works projects across the country. In Alabama, the CCC enrolled 67,000 young men, at a cost of $16 million. The CCC workforce is best remembered for its efforts at reforestation and forest management, erosion control, and construction and preservation in the nation’s parks and reserves. In Alabama, workers built trails, cabins, and recreational facilities in 17 state parks, including DeSoto, Chewacla, and Cheaha, before the program ended in 1942.

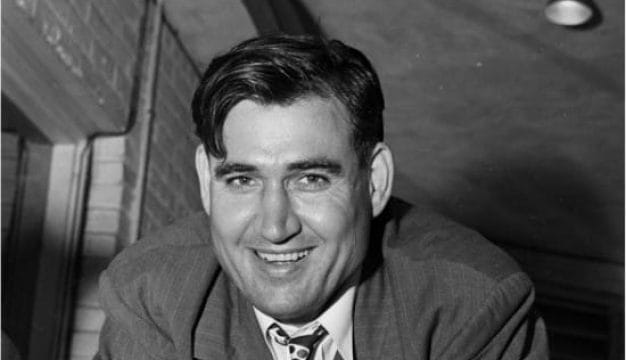

Aubrey Williams

Also beginning in 1933, the Civil Works Administration allocated $15 million to temporarily employ some 129,000 Alabamians. Its successor, the 1935 Works Progress Administration program (WPA), employed 63,000 Alabamians on thousands of building and improvement projects, including airports, public buildings, and engineering surveys, and oversaw construction of almost 21,000 miles of roads and highways. One of Roosevelt’s closest advisors, Harry Hopkins, ran both the CWA and the WPA. Hopkins, in turn, relied heavily on Alabamian Aubrey Williams after he suffered an extended illness and became distracted by increased responsibility within the Roosevelt administration.

Aubrey Williams

Also beginning in 1933, the Civil Works Administration allocated $15 million to temporarily employ some 129,000 Alabamians. Its successor, the 1935 Works Progress Administration program (WPA), employed 63,000 Alabamians on thousands of building and improvement projects, including airports, public buildings, and engineering surveys, and oversaw construction of almost 21,000 miles of roads and highways. One of Roosevelt’s closest advisors, Harry Hopkins, ran both the CWA and the WPA. Hopkins, in turn, relied heavily on Alabamian Aubrey Williams after he suffered an extended illness and became distracted by increased responsibility within the Roosevelt administration.

In addition to providing much-needed employment, the WPA also offered adult educational programs in literacy and homemaking. Such programs allowed women, many of whom were excluded from employment programs because of assumptions about women’s roles as wives and mothers, to benefit from the reforms of the New Deal. Before its dissolution in 1943, the agency paid a total of $116 million in wages to Alabama workers.

In addition to laborers, the WPA also employed people in the arts on projects designed to boost public morale and preserve local culture. The Federal Theater Project employed actors and directors, including African Americans in one of several segregated “Negro Units,” as they were known at the time, to put on plays in Birmingham. The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) paid men and women writers and researchers to produce official city and state guides, collect folklore and oral histories, and create fictional works for children and adults. A key accomplishment of the FWP in Alabama was collecting and preserving slave narratives, stories, and songs through in-person interviews. The Federal Art Project employed artists to teach classes in painting, pottery, weaving, and carving and create public art projects, most notably large-scale murals for public buildings across the country. Alabama’s most famous WPA artist was John Augustus Walker of Mobile, who painted colorful murals in Mobile’s Old City Hall complex, as well as in Birmingham school buildings and the city’s federal courthouse complex.

Aid for Agriculture

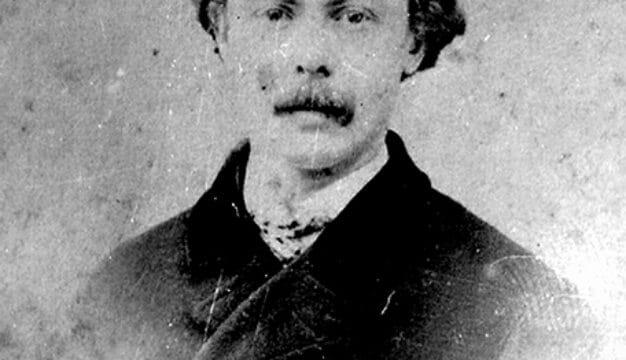

John Hollis Bankhead II

Several New Deal programs addressed worsening agricultural conditions in the South. In Alabama, the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) provided government subsidies to landowners willing to limit cotton production in an effort to increase commodity prices. The AAA was backed in its efforts by Sen. John H. Bankhead II and his brother, Rep. William B. Bankhead. The pair pushed legislation encouraging farmers to diversify their crops to ease the stranglehold cotton had on Alabama’s economy, but the laws had unintended outcomes. Pressure from the American Farm Bureau Federation and its leader, Alabama’s Edward O’Neal III, led AAA officials to issue payments to landowners and not the tenants and sharecroppers who worked the land. Thus many poor farmers were displaced as owners cut their acreage and used subsidy checks to replace laborers with tractors and other labor-saving implements. When the Supreme Court invalidated the AAA in 1936, John Bankhead revised the law to ensure that farmers could use crops as collateral for federal loans.

John Hollis Bankhead II

Several New Deal programs addressed worsening agricultural conditions in the South. In Alabama, the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) provided government subsidies to landowners willing to limit cotton production in an effort to increase commodity prices. The AAA was backed in its efforts by Sen. John H. Bankhead II and his brother, Rep. William B. Bankhead. The pair pushed legislation encouraging farmers to diversify their crops to ease the stranglehold cotton had on Alabama’s economy, but the laws had unintended outcomes. Pressure from the American Farm Bureau Federation and its leader, Alabama’s Edward O’Neal III, led AAA officials to issue payments to landowners and not the tenants and sharecroppers who worked the land. Thus many poor farmers were displaced as owners cut their acreage and used subsidy checks to replace laborers with tractors and other labor-saving implements. When the Supreme Court invalidated the AAA in 1936, John Bankhead revised the law to ensure that farmers could use crops as collateral for federal loans.

Roosevelt also signed into legislation a number of programs to help poor and landless farmers. The Rural Rehabilitation Program (RHP) of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided credit so that poor farmers could rent land and equipment and purchase feed, seed, and supplies; by December 1934, the program had assisted 115,000 Alabamians. Passed as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in 1933, subsistence homesteads provisions promoted by John Bankhead dedicated $25 million to help farmers obtain farmland through federally backed loans. The Rural Rehabilitation and the Subsistence Homesteads programs merged with other rural assistance efforts in 1935 to become the Resettlement Administration.

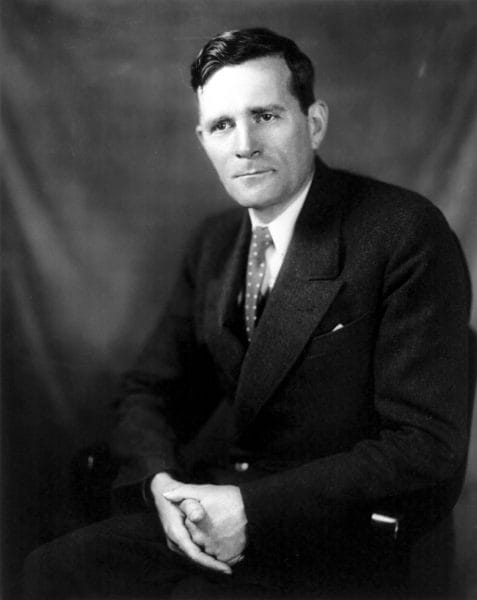

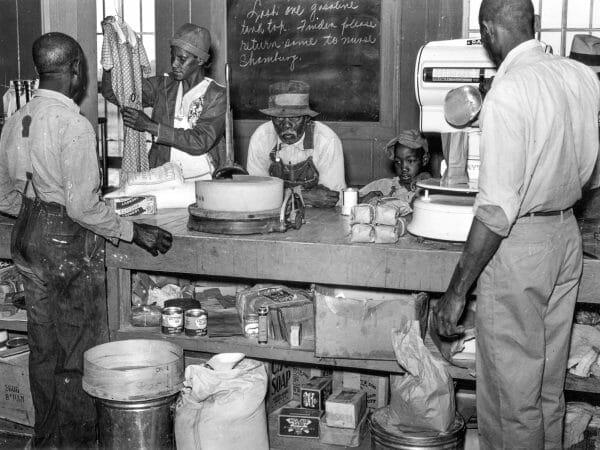

Gee’s Bend Cooperative Store

Alabama received more than its share of agricultural assistance, thanks largely to Sen. Bankhead’s influence. In fact, nearly a fourth of the national appropriation of the subsistence funds went to a handful of farms in central Alabama, including Bankhead Farms near Jasper in Walker County. In north Alabama, Skyline Farms, north of Scottsboro in Jackson County, established 181 small farms for white farmers from nearby relief rolls. African Americans found similar opportunities at Prairie Farms in Macon County and at Gee’s Bend in Wilcox County. These programs allowed many African Americans to purchase the land they had worked for decades. In 1937, Bankhead and Rep. John Marvin Jones of Texas wrote the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, which provided long-term, low-interest loans so tenant farmers could purchase land under the Farm Security Administration (FSA). The FSA also provided enduring images of rural and urban poverty in Alabama, most famously in the work of photographer Walker Evans, who collaborated with writer James Agee to document the lives of sharecropping families in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Gee’s Bend Cooperative Store

Alabama received more than its share of agricultural assistance, thanks largely to Sen. Bankhead’s influence. In fact, nearly a fourth of the national appropriation of the subsistence funds went to a handful of farms in central Alabama, including Bankhead Farms near Jasper in Walker County. In north Alabama, Skyline Farms, north of Scottsboro in Jackson County, established 181 small farms for white farmers from nearby relief rolls. African Americans found similar opportunities at Prairie Farms in Macon County and at Gee’s Bend in Wilcox County. These programs allowed many African Americans to purchase the land they had worked for decades. In 1937, Bankhead and Rep. John Marvin Jones of Texas wrote the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, which provided long-term, low-interest loans so tenant farmers could purchase land under the Farm Security Administration (FSA). The FSA also provided enduring images of rural and urban poverty in Alabama, most famously in the work of photographer Walker Evans, who collaborated with writer James Agee to document the lives of sharecropping families in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) aimed to address rural poverty by better managing resources and producing electricity along the Tennessee River. The agency constructed several hydroelectric dams, including Guntersville Dam in Marshall County, and Wilson Dam near Florence, Lauderdale County. The TVA also made improvements to control flooding and navigation on the Tennessee River, employed workers in clearing land and construction jobs, offered education and training programs, controlled malaria-spreading mosquitoes, and helped local municipalities attract industry with affordable electricity.

A New Deal for Labor and Industry

Gadsden Textile Strike

In Alabama and across the country, the Great Depression crippled industry with decreased consumption and increased unemployment. In addition, New Deal programs such as the AAA and TVA drove farmers off marginal land and into cities and towns in search of paying jobs. Several efforts provided relief for industrial workers and improved hours, wages, and conditions. The 1933 NIRA guaranteed the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively. But when industrial firms proved slow to implement the requirements of the NIRA and were hostile to unions, the newly organized workers went on strike. In 1934, encouraged by the United Mine Workers of America, thousands of Alabama miners walked out. That same year, workers at textile mills in Alabama and across the southern Piedmont struck to raise wages and reduce hours. The General Textile Strike, as it came to be known, spread through the Carolinas and into New England, but repression by mill owners, local police, and state authorities and a more general anti-union sentiment doomed the effort in Alabama. NIRA was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1935, but the National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 reinstituted some protections for unions, including minimum wage and maximum hour laws, respectively. Thereafter, Alabama’s labor standards quickly began to approach the national average.

Gadsden Textile Strike

In Alabama and across the country, the Great Depression crippled industry with decreased consumption and increased unemployment. In addition, New Deal programs such as the AAA and TVA drove farmers off marginal land and into cities and towns in search of paying jobs. Several efforts provided relief for industrial workers and improved hours, wages, and conditions. The 1933 NIRA guaranteed the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively. But when industrial firms proved slow to implement the requirements of the NIRA and were hostile to unions, the newly organized workers went on strike. In 1934, encouraged by the United Mine Workers of America, thousands of Alabama miners walked out. That same year, workers at textile mills in Alabama and across the southern Piedmont struck to raise wages and reduce hours. The General Textile Strike, as it came to be known, spread through the Carolinas and into New England, but repression by mill owners, local police, and state authorities and a more general anti-union sentiment doomed the effort in Alabama. NIRA was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1935, but the National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 reinstituted some protections for unions, including minimum wage and maximum hour laws, respectively. Thereafter, Alabama’s labor standards quickly began to approach the national average.

Social Security and Welfare

Roosevelt campaigned more aggressively beginning in 1935 to address economic inequality, implementing a series of reform-minded programs in what was termed the “Second New Deal.” Most notable was the Social Security Act, which provided a joint system of federal and state pension, unemployment insurance, and welfare programs. The influx of federal funds allowed Alabama to revitalize and restructure state relief efforts. Gov. Bibb Graves scrapped the struggling Child Welfare Department and created the Department of Public Welfare to receive and disperse funds to needy children, the elderly, disabled Alabamians, unemployed women, and dependent mothers.

Alabama’s “New Dealers”

Miners in Birmingham, 1937

A surprising outcome of the New Deal was the emergence of strikingly liberal governments at the state and federal levels. In 1934, former governor Bibb Graves won a second, nonconsecutive term by appealing to small farmers and laborers and exploiting their growing support for the New Deal. His opponent, Birmingham attorney Frank Dixon, represented business interests and planters. These so-called “Big Mules” of Alabama politics, as Graves called them in the campaign, feared the social and economic consequences of reform. In office, Graves furthered the New Deal’s reach in Alabama by creating the Alabama Department of Labor and staffed it with union-friendly officials who pushed for tougher child labor laws and supported striking workers. Graves also passed important education reforms, providing free textbooks for children through the third grade and mandating a minimum school term of seven months. He extended funding for highways and road building and created the state’s social welfare system. In many ways, the reform-minded Graves mirrored the efforts of the Roosevelt administration, seeking progressive solutions to the problems of a depressed economy.

Miners in Birmingham, 1937

A surprising outcome of the New Deal was the emergence of strikingly liberal governments at the state and federal levels. In 1934, former governor Bibb Graves won a second, nonconsecutive term by appealing to small farmers and laborers and exploiting their growing support for the New Deal. His opponent, Birmingham attorney Frank Dixon, represented business interests and planters. These so-called “Big Mules” of Alabama politics, as Graves called them in the campaign, feared the social and economic consequences of reform. In office, Graves furthered the New Deal’s reach in Alabama by creating the Alabama Department of Labor and staffed it with union-friendly officials who pushed for tougher child labor laws and supported striking workers. Graves also passed important education reforms, providing free textbooks for children through the third grade and mandating a minimum school term of seven months. He extended funding for highways and road building and created the state’s social welfare system. In many ways, the reform-minded Graves mirrored the efforts of the Roosevelt administration, seeking progressive solutions to the problems of a depressed economy.

In Washington, D.C., Alabama’s congressional delegation also eagerly supported Roosevelt and the New Deal. Most notably, Sen. Hugo Black became a key advisor to Roosevelt during his 1936 reelection campaign and was nominated by Roosevelt to the Supreme Court in 1938. As mentioned above, the Bankhead brothers backed numerous programs to provide aid for the rural and agricultural poor. Rep. Lister Hill supported public works programs and assisted with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Rep. George Huddleston and his successor, Luther Patrick, both supported Roosevelt’s efforts, and Henry Steagall helped solve the banking crisis through his co-sponsorship of the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated commercial and investment banks and provided deposit insurance for most bank customers.

New Deal Liberalism in Alabama

Clifford and Virginia Durr

During this era, the state’s elected officials continued to support white supremacy, but other Alabamians challenged inequality. The WPA’s Aubrey Williams fought to extend aid and educational programs to the poor regardless of race. Clifford and Virginia Durr became involved with the Washington, D.C.-based Alabama Policy Committee after Clifford took a position with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The group consisted of reform-minded citizens and also included Aubrey Williams; Gould Beech, editor of the Montgomery Advertiser; Jimmy Faulkner, editor of the Baldwin Times; and Auburn University professor Ralph Draughon. Members called for an end to regionally discriminatory freight rates, equality in the justice system, and a repeal of the poll tax. In 1938, Virginia Durr helped found the Southern Conference for Human Welfare to address issues related to economic and racial justice.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

During this era, the state’s elected officials continued to support white supremacy, but other Alabamians challenged inequality. The WPA’s Aubrey Williams fought to extend aid and educational programs to the poor regardless of race. Clifford and Virginia Durr became involved with the Washington, D.C.-based Alabama Policy Committee after Clifford took a position with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The group consisted of reform-minded citizens and also included Aubrey Williams; Gould Beech, editor of the Montgomery Advertiser; Jimmy Faulkner, editor of the Baldwin Times; and Auburn University professor Ralph Draughon. Members called for an end to regionally discriminatory freight rates, equality in the justice system, and a repeal of the poll tax. In 1938, Virginia Durr helped found the Southern Conference for Human Welfare to address issues related to economic and racial justice.

The Legacy of the New Deal

Several factors combined to dampen support for the New Deal in Alabama. Conservatives, led by the Big Mules, began to make electoral gains. In 1938, Frank Dixon defeated the more moderate Chauncey Sparks to win the governorship and reversed many of Graves’s accomplishments, folded the Department of Labor into another agency, and called out the Alabama National Guard to break strikes. In Congress, Alabama’s anti-New Deal sentiment was best embodied by Frank Boykin, who relied on personal wealth, conservative politics, and opposition to civil rights to win political office. There, Boykin ignored the demands of poor farmers and organized labor, criticized an active government that interfered in the workings of the economy and society (and, by extension, the spirit of the New Deal), and defended segregation.

World War II Welder

New Deal reforms did not solve the Great Depression. Not until the economic boom of World War II did national, state, and local economies begin to recover. Nevertheless, federal agencies and reform efforts transformed Alabama farms and factories, towns and cities in important ways. Poor and marginal farmers were driven off the land, thereby concentrating remaining farms in the hands of larger, profit-driven landholders. Between 1930 and 1940, the number of tenants fell by 50,000 to 117,000 whereas the number of owners rose from 5,000 to 80,000. Electrification, especially in rural areas, was a key improvement, and the number of farms with electricity rose from 4,000 in 1930 to 36,000 in 1940. By 1940, unemployment had fallen below 7 percent, mostly from increased defense employment, and only about 5 percent of Alabamians remained on public works payrolls. The New Deal also greatly affected organized labor in Alabama. Backed by federal protections, more than 65,000 workers joined unions in the Birmingham District alone, and nearly 90 percent of mining labor was unionized.

World War II Welder

New Deal reforms did not solve the Great Depression. Not until the economic boom of World War II did national, state, and local economies begin to recover. Nevertheless, federal agencies and reform efforts transformed Alabama farms and factories, towns and cities in important ways. Poor and marginal farmers were driven off the land, thereby concentrating remaining farms in the hands of larger, profit-driven landholders. Between 1930 and 1940, the number of tenants fell by 50,000 to 117,000 whereas the number of owners rose from 5,000 to 80,000. Electrification, especially in rural areas, was a key improvement, and the number of farms with electricity rose from 4,000 in 1930 to 36,000 in 1940. By 1940, unemployment had fallen below 7 percent, mostly from increased defense employment, and only about 5 percent of Alabamians remained on public works payrolls. The New Deal also greatly affected organized labor in Alabama. Backed by federal protections, more than 65,000 workers joined unions in the Birmingham District alone, and nearly 90 percent of mining labor was unionized.

The ideals of the New Deal shaped state politics, at least in some areas, well after World War II. In the 1940s and 1950s, a number of congressmen, including Lister Hill, John Sparkman, Robert E. “Bob” Jones, and Carl Elliott, fought to expand federal funding and support for education, healthcare, utilities, housing, agriculture, and small businesses. At the state level, James E. “Big Jim” Folsom, a disciple of Bibb Graves, won the governorship in 1946 by appealing to the farmers and workers who had benefitted from the New Deal. Folsom built farm-to-market roads, increased state funding for pensions, education, and welfare, and attempted to reapportion the state legislature and revise the constitution. And, unlike many of his fellow New Dealers, he willingly challenged racial inequality. A number of New Dealer women held prominent public office, including Loula Dunn in the Department of Public Welfare and Daisy Donovan and Molly Dowd in the Department of Labor. Suffragist Pattie Ruffner Jacobs was an advisor to the Alabama Consumer Advisory Board.

African Americans also made important, albeit limited, gains. Some New Deal programs attempted to include African Americans in the general planning and relief process, but black New Dealers were largely expected to serve only black communities. Black farmers occasionally benefitted from agricultural reforms, although rarely at the level of whites, and some unions were open to African American members. Segregation, however, proved resilient. As opposition to the New Deal increased in the late 1930s, so did pressure on Alabama’s politicians to uphold segregation. Likewise, Alabamians like Aubrey Williams and the Durrs who questioned segregation were increasingly isolated.

Overall though, the New Deal had a profound impact on Alabama. Its programs and projects created jobs and raised incomes during the country’s worst economic crisis. And, in a state dominated by conservative politicians and strict social and racial hierarchies, the New Deal created an environment for alternative ideas, liberal politics, and opportunities for farm workers, labor unionists, women, and African Americans to influence Alabama government and society. As the state prepared to participate in the defense effort surrounding World War II, and as New Deal agencies adapted to meet wartime needs or dissolved in the face of shifting priorities, the changes evoked by Roosevelt’s program of relief and reform became the foundation for the greater transformation that reshaped Alabama and the South in the postwar era.

Further Reading

- Badger, Anthony J. New Deal/New South. Fayetteville, Ark.: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

- Biles, Roger. The South and the New Deal. Lexington, Ky.: University of Kentucky Press, 1994.

- Brown, James Seay Jr., ed. Up Before Daylight: Life Histories from the Alabama Writers’ Project, 1938-1939. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1982.

- Downs, Matthew. Transforming the South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

- Jackson, Harvey H., III, ed. The WPA Guide to 1930s Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. New York: Harper Perennial, 1963.

- Roberts, Charles Kenneth. “New Deal Community-Building in the South: The Subsistence Homesteads around Birmingham, Alabama.” Alabama Review 66 (April 2013): 83-121.