Alabama Foodways

Lane Cake

Alabama food culture fits into the broader concept of southern food culture, which resulted from a blending of African, European, and Native American traditions in the New World. Over many generations, southern food became a vital component of southern culture, owing to a host of factors including a long reliance on subsistence farming, food’s unifying effects in frontier and rural communities, and the South’s poverty and defeat in the Civil War. The term “foodways” includes all of the cultural and historical meanings that surround food itself. The term recognizes that each food tradition is a mix of converging factors, including geography, economy, customs, politics, and events, and that food represents a vital part of every culture’s heritage. Further, food traditions can be used as gateways for exploring culture and history.

Lane Cake

Alabama food culture fits into the broader concept of southern food culture, which resulted from a blending of African, European, and Native American traditions in the New World. Over many generations, southern food became a vital component of southern culture, owing to a host of factors including a long reliance on subsistence farming, food’s unifying effects in frontier and rural communities, and the South’s poverty and defeat in the Civil War. The term “foodways” includes all of the cultural and historical meanings that surround food itself. The term recognizes that each food tradition is a mix of converging factors, including geography, economy, customs, politics, and events, and that food represents a vital part of every culture’s heritage. Further, food traditions can be used as gateways for exploring culture and history.

In Alabama, for example, Lane cake speaks to Alabama women’s roles in the Progressive Era. Banana pudding signifies the banana docks in Mobile, crucial to the local economy for 50 years. Peanuts reveal a long history of African American heritage in the state, as well as the individual stories of George Washington Carver, the boll weevil, and the Wiregrass. Sweet potato pie symbolizes civil rights and soul food in Montgomery, and gumbo reflects Creole culture on the Gulf Coast. Immigrant communities—including Greeks, Southeast Asians, Koreans, and Latinos—also have shaped Alabama food culture in unique ways.

Barbecuing Chicken

Alabama food traditions also illuminate the diversity of history, culture, and environment within the state’s borders. Fried cornbread and layer cakes are Wiregrass specialties, whereas seafood gumbo reigns along the coast. Tennessee Valley chicken stew is made in just a handful of north Alabama counties. Cornmeal is yellow in the north and white in the south. Syrup is sorghum in the north and cane in the south. And the state boasts at least six distinct regional variations of barbecue sauce: tomato-based Tennessee in pockets throughout the state; Greek influenced ketchup sauces in Birmingham; north Alabama’s vinegar base; spicy orange mustard in east Alabama that bear a South Carolina influence; pecan spiced coastal sauces, reflecting the large pecan industry in Mobile and Baldwin counties; and Decatur’s own specialty: white sauce made from mayonnaise, apple cider vinegar, and lemon juice.

Barbecuing Chicken

Alabama food traditions also illuminate the diversity of history, culture, and environment within the state’s borders. Fried cornbread and layer cakes are Wiregrass specialties, whereas seafood gumbo reigns along the coast. Tennessee Valley chicken stew is made in just a handful of north Alabama counties. Cornmeal is yellow in the north and white in the south. Syrup is sorghum in the north and cane in the south. And the state boasts at least six distinct regional variations of barbecue sauce: tomato-based Tennessee in pockets throughout the state; Greek influenced ketchup sauces in Birmingham; north Alabama’s vinegar base; spicy orange mustard in east Alabama that bear a South Carolina influence; pecan spiced coastal sauces, reflecting the large pecan industry in Mobile and Baldwin counties; and Decatur’s own specialty: white sauce made from mayonnaise, apple cider vinegar, and lemon juice.

Native American and Frontier Influences

Native American Foods

The Alabama food story begins with the cultivation of corn by Native Americans in the Mississippian Period (1000-1500), which revolutionized Native American life in eastern and southern North America. The initiation of horticulture resulted in a shift in Native American settlement patterns from nomadic hunting and gathering activities to sedentary agrarian communities, such as at Moundville in Tuscaloosa County. Native Americans consumed many varieties of corn in many ways: raw, boiled, fried, roasted, ground into meal, flour, and grits, and mixed with vegetables to make stew. When Europeans began settling in the present-day United States in the early 1600s, corn spared them from starvation when their crops of wheat and barley failed, as Native Americans taught them how to plant, harvest, process, prepare, and store the grain.

Native American Foods

The Alabama food story begins with the cultivation of corn by Native Americans in the Mississippian Period (1000-1500), which revolutionized Native American life in eastern and southern North America. The initiation of horticulture resulted in a shift in Native American settlement patterns from nomadic hunting and gathering activities to sedentary agrarian communities, such as at Moundville in Tuscaloosa County. Native Americans consumed many varieties of corn in many ways: raw, boiled, fried, roasted, ground into meal, flour, and grits, and mixed with vegetables to make stew. When Europeans began settling in the present-day United States in the early 1600s, corn spared them from starvation when their crops of wheat and barley failed, as Native Americans taught them how to plant, harvest, process, prepare, and store the grain.

Alabama saw its greatest influx of settlers from 1810 to 1830, when large numbers of migrants seeking land flooded into present-day Alabama from Tennessee, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia during the period known as “Alabama Fever.” Many of these pioneers were Scots-Irish immigrants who had come to America in great numbers between 1710 and 1775. They brought with them European food traditions adapted to American foodstuffs, Native American techniques, and local growing conditions.

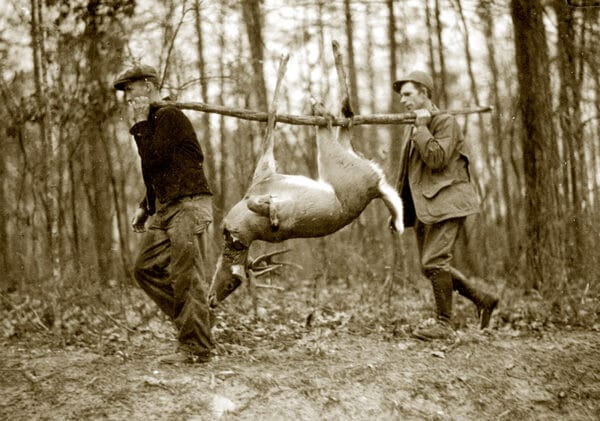

Alabama Deer Hunters

Upon arrival, Alabama pioneers depended on the streams and forests for sustenance until the first harvest. Frontier families subsisted mainly on cornbread, vegetables from the garden, wild peas and nuts, and wild game from the woods, including elk, deer, and turkey. Along the Gulf Coast, early settlers followed Native American examples by shrimping, fishing, and gathering oysters and clams.

Alabama Deer Hunters

Upon arrival, Alabama pioneers depended on the streams and forests for sustenance until the first harvest. Frontier families subsisted mainly on cornbread, vegetables from the garden, wild peas and nuts, and wild game from the woods, including elk, deer, and turkey. Along the Gulf Coast, early settlers followed Native American examples by shrimping, fishing, and gathering oysters and clams.

Virtually every pioneer’s first task was to clear enough land to plant a crop of corn, which gave a high yield that allowed pioneer families to survive on just a few acres of land. In fact, corn was planted on at least half of every Alabama farm’s acreage, providing basic sustenance for families and livestock. Consumed in some form at nearly every meal, corn also provided a foundation for beer and whiskey, a batter to fry fish, a starch, and a sweetener. And corn’s utility extended beyond the table: its silks, husks, stalks and cobs served a range of household purposes. By 1849, the South had 18 million acres planted in corn, compared to 5 million in cotton. And southerners continued to depend on corn as the most significant component of their diet until the 1940s.

Meat was rarely consumed in large quantities. Until the Civil War, much of Alabama remained a frontier in which domestic animals played a small role. Hogs, present in Alabama since colonial days, foraged through the woods at will and were captured and killed at the start of winter, making pork the main meat component of the Alabama diet. Barbecue (the slow roasting of meat over a low fire) claims a long history in Alabama as the centerpiece of frontier gatherings, community fundraisers, and modern social events. In Alabama, barbecue is synonymous with pork.

African Influences

Gumbo

In addition to the thousands of white settlers streaming into the state, thousands of enslaved West Africans came to Alabama in the nineteenth century to work on rapidly expanding cotton plantations. These slaves were largely responsible for fusing African, European, and Native American traditions to create a distinct southern food identity. Gumbo, a seafood stew long popular along the Gulf Coast, perfectly showcases this blend: its base is of African or Native American origin; okra was brought from Africa; hot peppers from the Caribbean; black pepper from Madagascar; salt from the French and Native Americans; tomatoes and red pepper from the Spanish via the Canary Islands; shrimp, crab, and oysters came from coastal waters; and ground sassafras leaves known as filé from the Choctaws. Choctaw women once sold packets of filé in the streets of Mobile, and sassafras trees still grow wild along the Gulf Coast, lining the bluffs of the Mobile River. Gumbo is also inextricably linked to Mardi Gras traditions in African American and Creole communities in Mobile.

Gumbo

In addition to the thousands of white settlers streaming into the state, thousands of enslaved West Africans came to Alabama in the nineteenth century to work on rapidly expanding cotton plantations. These slaves were largely responsible for fusing African, European, and Native American traditions to create a distinct southern food identity. Gumbo, a seafood stew long popular along the Gulf Coast, perfectly showcases this blend: its base is of African or Native American origin; okra was brought from Africa; hot peppers from the Caribbean; black pepper from Madagascar; salt from the French and Native Americans; tomatoes and red pepper from the Spanish via the Canary Islands; shrimp, crab, and oysters came from coastal waters; and ground sassafras leaves known as filé from the Choctaws. Choctaw women once sold packets of filé in the streets of Mobile, and sassafras trees still grow wild along the Gulf Coast, lining the bluffs of the Mobile River. Gumbo is also inextricably linked to Mardi Gras traditions in African American and Creole communities in Mobile.

Dishes created by African American cooks were consumed by black and white southerners alike. By the mid-nineteenth century, the most influential and popular American cookbooks all contained recipes featuring African ingredients, including okra, field peas, eggplant, greens, cayenne pepper, sesame seeds, and peanuts. The cookbooks also noted African food pairings and cooking techniques, including combining beans and rice and heavily spicing soups.

The Alabama Diet

Alabamians, both black and white, ate what they could grow, find wild, or acquire through purchase or trade. Despite popular images of endless cotton plantations, until World War II most Alabama families lived on subsistence farms where they spent most of their hours planting, harvesting, and processing foods consumed at home. Enslaved Alabamians often grew vegetables on small patches of land to augment their meager diets, and most emancipated blacks remaining in Alabama continued to live by subsistence farming.

Robinson-Dillworth Plantation Kitchen Garden

With vegetables at its core, Alabama cuisine necessarily followed the seasons, with fresh and seasonal ingredients being an essential quality of home cooking. Vegetables paired with cornbread and occasionally hog meat defined the Alabama diet for generations. Upon harvest, vegetables were eaten fresh or were canned and stored in cellars. Peas arrived first in the spring, then summer squashes, followed by tomatoes, corn, okra, many kinds of beans, peppers, and beets. Fall brought sweet potatoes, winter squashes, and a wide variety of greens, including collard, turnip, kale, and mustard. During the Civil War, widespread poverty and food shortages expanded the variety of vegetables on the Alabama table. With the countryside stripped bare by hungry soldiers of both armies, particularly in northern Alabama, Alabamians of all classes reverted to foraging.

Robinson-Dillworth Plantation Kitchen Garden

With vegetables at its core, Alabama cuisine necessarily followed the seasons, with fresh and seasonal ingredients being an essential quality of home cooking. Vegetables paired with cornbread and occasionally hog meat defined the Alabama diet for generations. Upon harvest, vegetables were eaten fresh or were canned and stored in cellars. Peas arrived first in the spring, then summer squashes, followed by tomatoes, corn, okra, many kinds of beans, peppers, and beets. Fall brought sweet potatoes, winter squashes, and a wide variety of greens, including collard, turnip, kale, and mustard. During the Civil War, widespread poverty and food shortages expanded the variety of vegetables on the Alabama table. With the countryside stripped bare by hungry soldiers of both armies, particularly in northern Alabama, Alabamians of all classes reverted to foraging.

As the frontier transformed into permanent farms and townships, cows and goats were increasingly kept for milk and chickens for eggs. Farmers continued to obtain honey from bees and syrup from sugar cane or sorghum. Desserts were based on wild fruits: peaches, apples, pears, figs, strawberries, and blackberries that were also canned, dried, or preserved. Cobblers were popular, made from fruit and simple ingredients, as were white cakes, custards, and cookies. Homemade peanut brittle and popcorn balls were holiday favorites.

Despite its current ubiquity, fried chicken was long considered a luxury in Alabama. Until the mid-twentieth century, farmers maintained flocks of chickens mainly for their eggs, a source of year-round nourishment and supplementary income. Most chickens were killed only when they were too old to produce eggs and usually were put into stews, as only a long, slow simmer could make the meat tender. Because tasty fried chicken demands a young bird, it was a delicacy reserved for Sunday dinners and special occasions. At mid-century, when the poultry industry morphed into a large agribusiness, chickens became more affordable, and fried chicken became daily fare in Alabama.

Women were largely responsible for processing, preserving, and cooking farm foods. Because baking fell squarely into their domain, women often built their cooking reputations around desserts, which still comprise half of any Alabama community meal today, including church picnics, family reunions, decoration days, and funeral gatherings. At the end of the nineteenth century, thanks to the new, widespread availability of white flour and the invention of baking powder, cake making took on a particular fervor in the South. Women created a number of extravagant cakes at this time, including the Lane cake, invented in Clayton, Barbour County.

In the rural existence that dominated Alabama life, food-centered gatherings provided a vital social outlet. Cane grindings, chicken stews, and peanut boils became major fellowship opportunities for rural communities. Over time, these rural food-centered gatherings grew into traditions emblematic of Alabama identity, so that even when Alabamians moved to urban and suburban places, they still gathered for fish fries.

The End of Subsistence Farming

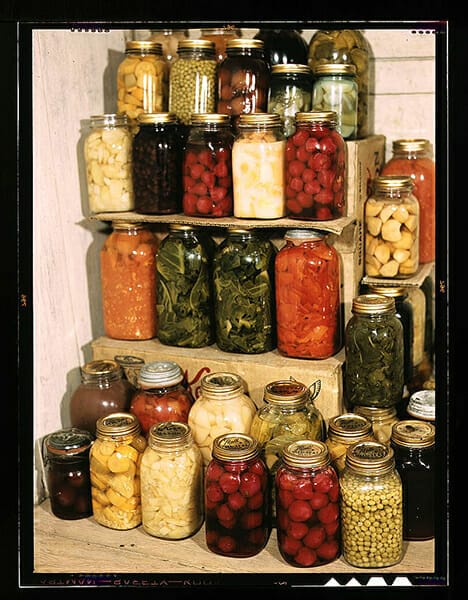

Canned Fruits and Vegetables

In the early 1940s, the war industries that brought the United States out of the Great Depression transformed the way Alabamians grew, cooked, and ate food. With women entering the workforce in droves during World War II, families increasingly relied on new industrialized and convenience foods, including factory-made bread and cake mixes, frozen foods, and canned goods. In most families, labor-intensive cooking was relegated to Sundays and holidays. Further, from 1940 to 1970, the number of Alabama farms decreased by 66 percent. The mechanization of agriculture caused a decline in the need for farm labor and changes in government farm policy that enabled the cultivation of large tracts of land, paving the way for agribusiness and discouraging small farming. Urbanization, increased travel on new highways, radio and later television advertising, and the rising popularity of fast food dramatically changed the agricultural landscape. By the 1960s, millions of southern farmers and their families had relocated to cities or suburbs. The era of subsistence farming that had dominated the South for a thousand years had come to an end.

Canned Fruits and Vegetables

In the early 1940s, the war industries that brought the United States out of the Great Depression transformed the way Alabamians grew, cooked, and ate food. With women entering the workforce in droves during World War II, families increasingly relied on new industrialized and convenience foods, including factory-made bread and cake mixes, frozen foods, and canned goods. In most families, labor-intensive cooking was relegated to Sundays and holidays. Further, from 1940 to 1970, the number of Alabama farms decreased by 66 percent. The mechanization of agriculture caused a decline in the need for farm labor and changes in government farm policy that enabled the cultivation of large tracts of land, paving the way for agribusiness and discouraging small farming. Urbanization, increased travel on new highways, radio and later television advertising, and the rising popularity of fast food dramatically changed the agricultural landscape. By the 1960s, millions of southern farmers and their families had relocated to cities or suburbs. The era of subsistence farming that had dominated the South for a thousand years had come to an end.

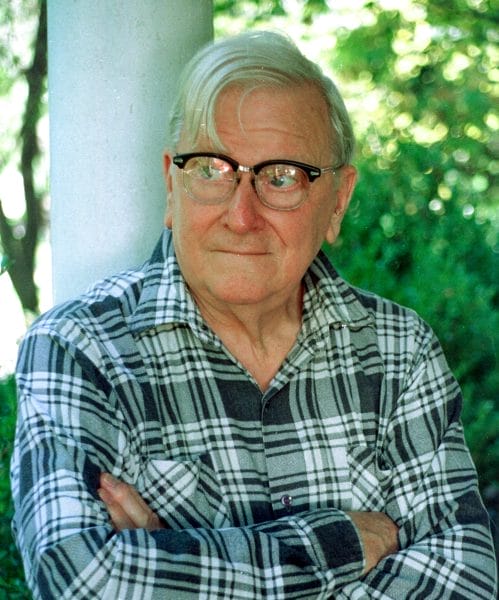

Eugene Walter

Many of those who left Alabama farms were African Americans heading north during the Great Migration, seeking better jobs, wages, and freedom from racial discrimination. These immigrants brought southern cooking, which became known as “soul food” in the 1960s, to northern cities, particularly New York, Detroit, and Chicago. In the South, cafés, diners, and “meat and threes” sprang up, offering the food southerners had cooked and enjoyed for generations. These restaurants became beloved gathering spots as southerners reinvented food traditions that had become so ingrained in the southern identity. Mobile author Eugene Walter notes that the South defiantly embraced and romanticized its past, including its foodways.

Eugene Walter

Many of those who left Alabama farms were African Americans heading north during the Great Migration, seeking better jobs, wages, and freedom from racial discrimination. These immigrants brought southern cooking, which became known as “soul food” in the 1960s, to northern cities, particularly New York, Detroit, and Chicago. In the South, cafés, diners, and “meat and threes” sprang up, offering the food southerners had cooked and enjoyed for generations. These restaurants became beloved gathering spots as southerners reinvented food traditions that had become so ingrained in the southern identity. Mobile author Eugene Walter notes that the South defiantly embraced and romanticized its past, including its foodways.

When small farming plummeted in Alabama, big agriculture rose to take its place. Today, agriculture remains an important industry for the state. In 2017, the top five commodities in Alabama were poultry, cattle, chicken eggs, cotton, and soybeans. Together, they brought in $4.9 billion of revenue. Alabama also has significant production in greenhouse, sod, and nursery products, grains, catfish, peanuts, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and pecans. Together, agriculture, forestry, and related industries have a $70.4 billion economic impact on Alabama and provide more than 580,000 jobs.

Preserving the Traditions

Frank Stitt’s Baked Grits

In the 1970s, southerners began fighting to preserve a traditional food culture increasingly replaced by fast and convenience foods. The decade saw a renaissance of barbecue joints and a surge in farmers’ markets and food-centered festivals. Southerners’ efforts to preserve their food heritage captured national attention, and interest in southern food soared. In recent decades, southern food has increased in popularity through cookbooks, magazines, restaurants, barbecue contests, food tours, and food travelogues. In Alabama, progressive chefs began a push to return to pre-WWII southern cooking. Chefs such as Frank Stitt, Lucy Buffet, Chris Hastings, Wesley True, James Boyce, James Lewis, and Chris Dupont focus on using fresh, local, and seasonal ingredients at their renowned Alabama restaurants. In addition, Geneva County native and chef Scott Peacock began a documentary project interviewing elderly Alabamians about food traditions to help preserve Alabama’s singular food knowledge and heritage.

Frank Stitt’s Baked Grits

In the 1970s, southerners began fighting to preserve a traditional food culture increasingly replaced by fast and convenience foods. The decade saw a renaissance of barbecue joints and a surge in farmers’ markets and food-centered festivals. Southerners’ efforts to preserve their food heritage captured national attention, and interest in southern food soared. In recent decades, southern food has increased in popularity through cookbooks, magazines, restaurants, barbecue contests, food tours, and food travelogues. In Alabama, progressive chefs began a push to return to pre-WWII southern cooking. Chefs such as Frank Stitt, Lucy Buffet, Chris Hastings, Wesley True, James Boyce, James Lewis, and Chris Dupont focus on using fresh, local, and seasonal ingredients at their renowned Alabama restaurants. In addition, Geneva County native and chef Scott Peacock began a documentary project interviewing elderly Alabamians about food traditions to help preserve Alabama’s singular food knowledge and heritage.

Additional Resources

Blejwas, Emily. The Truth of the Radish: Fourteen Foods Tell the Story of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2014.

Edge, John T., ed. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Foodways. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Fowler, Damon Lee. Classical Southern Cooking. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1995.

Hardeman, Nicholas. Shucks, Shocks, and Hominy Blocks: Corn as a Way of Life in Pioneer America. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

Harris, Jessica. High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2011.

Rogers, William Warren, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt, eds. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

Tapper, Monica. A Culinary Tour Through Alabama History. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2021.

Wright, Lolla W. “Alabama Appetites.” Alabama Review 17 (January 1964): 22-32.