Don Siegelman (1999-2003)

Don Siegelman, 1999

In November 1998 Don Siegelman (1946- ) won a landslide victory over incumbent Republican Forrest “Fob” James Jr. to become the first Democrat to win the Alabama governorship since 1982. He came into office endorsing a state lottery to raise money for education while avoiding the racial and religious issues that Alabama candidates traditionally used to stir the electorate. He had been touted as the first state governor to espouse “New South” principles, which aimed to modernize and improve the region’s image by promoting progressive ideas in business, education, and resource management. During Siegelman’s term, however, he was hampered by ethics charges that resulted in an indictment, conviction, and jail time after leaving office.

Don Siegelman, 1999

In November 1998 Don Siegelman (1946- ) won a landslide victory over incumbent Republican Forrest “Fob” James Jr. to become the first Democrat to win the Alabama governorship since 1982. He came into office endorsing a state lottery to raise money for education while avoiding the racial and religious issues that Alabama candidates traditionally used to stir the electorate. He had been touted as the first state governor to espouse “New South” principles, which aimed to modernize and improve the region’s image by promoting progressive ideas in business, education, and resource management. During Siegelman’s term, however, he was hampered by ethics charges that resulted in an indictment, conviction, and jail time after leaving office.

Don Eugene Siegelman was born on February 24, 1946, in Mobile, the son of Leslie Bouchet Siegelman and Andrea Schottgen Siegelman. He graduated from Mobile’s Murphy High School in 1964 and entered the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa that fall, where he was elected president of the Student Government Association in his junior year and earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1968. He then attended law school at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., graduating in 1972.

That summer, Siegelman returned to Alabama to coordinate the state campaign of Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern. Identified as an extreme liberal, McGovern was badly defeated in Alabama, and young Siegelman learned an important lesson. He retreated from liberalism and moved toward a more moderate approach to public issues. In 1973, Siegelman studied international law at Oxford University and then returned home to work for the Alabama Democratic Party. He was named executive director of the State Democratic Executive Committee, a position he held until 1978. In 1980, Siegelman married Lori Allen of Birmingham, with whom he had two children.

While working for the Democratic Party in Alabama, Siegelman coordinated efforts to streamline Alabama’s outmoded voting laws. In 1978, he became the state’s chief election official when he was elected secretary of state of Alabama, a position he won again in 1982. Near the end of his second term as secretary of state, Siegelman decided to run for state attorney general. Despite his law degree, his qualifications for the job were thin; he had never practiced law or tried a single case before a jury. Nonetheless, he won both the Democratic primary and the general election.

After four relatively quiet years as attorney general, in 1990 Siegelman joined a crowded field seeking the Democratic nomination for governor to run against incumbent Guy Hunt. The group included former governor Fob James, Alabama Education Association leader Paul Hubbert, and Congressman Ronnie Flippo. Siegelman received only 25 percent of the vote, but it was enough to move him into a runoff election with Hubbert. In the ensuing campaign, however, Hubbert took 53.6 percent of the vote, handing Siegelman his first political defeat, with Hunt ultimately winning the race.

No longer in public office, Siegelman opened a law practice in Montgomery and prepared for another statewide political race in 1994. Opting not to challenge incumbent governor Jim Folsom Jr. and Hubbert for governor, Siegelman ran for lieutenant governor. With support from many of the same groups that supported Hubbert—teachers unions, trial lawyers, and black political organizations—Siegelman won his runoff campaign and easily defeated former attorney general Charles Graddick, the Republican nominee, in the general election.

Don Siegelman Swearing In

The most controversial aspect of Siegelman’s term as lieutenant governor revolved around tort reform legislation aimed at limiting the size of civil jury verdicts. The business community believed that juries were being manipulated by trial lawyers into awarding overly large financial verdicts, which, they argued, thwarted economic development in the state. Trial lawyers argued that verdict limitations interfered with the sanctity of the jury system and plaintiffs’ rights. Siegelman, who had appointed all of the Alabama Senate‘s committee chairpersons, exercised enormous power over the flow of legislation to the floor of the Senate. When supporters of tort reform were unable to get their bills brought up for a vote, business leaders held Siegelman responsible. His support for stronger laws against drunk drivers was far less controversial and enjoyed universal support. Siegelman and his wife had been the victims of an accident caused by a drunk driver in which his wife was severely injured.

Don Siegelman Swearing In

The most controversial aspect of Siegelman’s term as lieutenant governor revolved around tort reform legislation aimed at limiting the size of civil jury verdicts. The business community believed that juries were being manipulated by trial lawyers into awarding overly large financial verdicts, which, they argued, thwarted economic development in the state. Trial lawyers argued that verdict limitations interfered with the sanctity of the jury system and plaintiffs’ rights. Siegelman, who had appointed all of the Alabama Senate‘s committee chairpersons, exercised enormous power over the flow of legislation to the floor of the Senate. When supporters of tort reform were unable to get their bills brought up for a vote, business leaders held Siegelman responsible. His support for stronger laws against drunk drivers was far less controversial and enjoyed universal support. Siegelman and his wife had been the victims of an accident caused by a drunk driver in which his wife was severely injured.

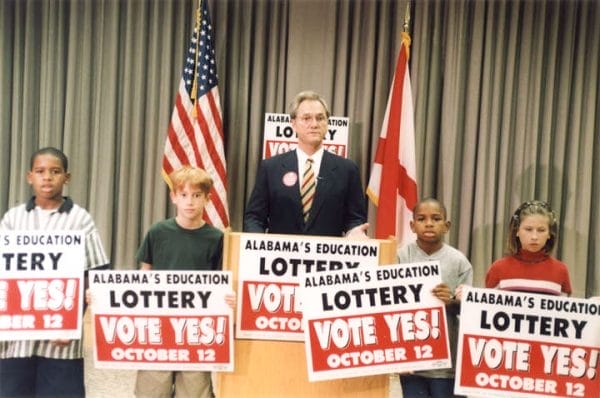

Gov. Siegelman Lottery Promotion Event

By late 1997, business leaders, although irritated with the lieutenant governor for killing tort reform, had grown weary of Fob James’s lackadaisical and erratic approach to governing the state. Siegelman took advantage of James’s loss of popularity and began to meet with strategic business leaders in the state, even promising them some degree of tort-reform legislation. He easily won the Democratic primary on a platform of initiating a lottery, modeled on Georgia’s, that would provide college scholarships. James, in contrast, endorsed no clear agenda, spent most of his campaign funds during the Republican primary, and was left dependent on the growing unpopularity of the Democrats among white voters to win reelection.

Gov. Siegelman Lottery Promotion Event

By late 1997, business leaders, although irritated with the lieutenant governor for killing tort reform, had grown weary of Fob James’s lackadaisical and erratic approach to governing the state. Siegelman took advantage of James’s loss of popularity and began to meet with strategic business leaders in the state, even promising them some degree of tort-reform legislation. He easily won the Democratic primary on a platform of initiating a lottery, modeled on Georgia’s, that would provide college scholarships. James, in contrast, endorsed no clear agenda, spent most of his campaign funds during the Republican primary, and was left dependent on the growing unpopularity of the Democrats among white voters to win reelection.

Democratic defeats in the gubernatorial elections of 1986, 1990, and 1994 had been caused by the slow erosion of support for the party among white middle-class voters, who largely expressed the view that their party had deserted them in favor of minorities and other special-interest groups. Siegelman, taking a cue from fellow southerner Pres. Bill Clinton, was determined to win back these voters in the 1998 election. His lottery idea was supported by the middle-class, which, together with voter apathy towards Fob James, led to Siegelman’s election with 57 percent of the vote. Voter interest was so high that more ballots were cast for Siegelman than for any gubernatorial candidate in Alabama’s history.

Honda Press Event in Talladega

Siegelman was the first person to have been elected to each of the state’s top three constitutional offices—governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general—and he was the first lieutenant governor since Thomas E. Kilby (1919-1923) to be elevated by voters from that post to the governor’s chair. He was also the first governor born and reared in the city of Mobile and the first Catholic, and his wife became the first Jewish woman to serve as Alabama’s First Lady. Once in office, Siegelman continued to emphasize the need for a lottery to support education. He also surprised many in his own party by supporting and pushing tort reform through the legislature. This legislation was promised as part of the state’s package of incentives that had prompted Honda Motor Company to locate a major manufacturing plant in Alabama, giving the state an economic boost. The legislature then passed an amendment to allow a lottery, but on October 12, 1999, the proposal was rejected 56 percent to 44 percent in a statewide referendum. Groups opposing the lottery initiative and another gambling measure in Alabama included the Alabama Christian Coalition and Citizens Against Legalized Lottery. These organizations reportedly received funding from the Choctaw tribe in Mississippi, which feared competition for its casino. Funds were provided to the Alabama groups by lobbyist Jack Abramoff and conservative political operative Ralph Reed. These actions resulted in federal and congressional investigations and jail time for Abramoff, who represented the Choctaws.

Honda Press Event in Talladega

Siegelman was the first person to have been elected to each of the state’s top three constitutional offices—governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general—and he was the first lieutenant governor since Thomas E. Kilby (1919-1923) to be elevated by voters from that post to the governor’s chair. He was also the first governor born and reared in the city of Mobile and the first Catholic, and his wife became the first Jewish woman to serve as Alabama’s First Lady. Once in office, Siegelman continued to emphasize the need for a lottery to support education. He also surprised many in his own party by supporting and pushing tort reform through the legislature. This legislation was promised as part of the state’s package of incentives that had prompted Honda Motor Company to locate a major manufacturing plant in Alabama, giving the state an economic boost. The legislature then passed an amendment to allow a lottery, but on October 12, 1999, the proposal was rejected 56 percent to 44 percent in a statewide referendum. Groups opposing the lottery initiative and another gambling measure in Alabama included the Alabama Christian Coalition and Citizens Against Legalized Lottery. These organizations reportedly received funding from the Choctaw tribe in Mississippi, which feared competition for its casino. Funds were provided to the Alabama groups by lobbyist Jack Abramoff and conservative political operative Ralph Reed. These actions resulted in federal and congressional investigations and jail time for Abramoff, who represented the Choctaws.

In response to the lottery defeat, Siegelman declared himself determined to improve education in the state but vowed that it had to be done without increasing taxes or reducing existing programs. During his term, he pushed through a statewide expansion of the Alabama Reading Initiative literacy program for K-12 children and signed an executive order just before leaving office enabling state workers to enroll their children in a state-run health insurance program.

Siegelman was defeated in his 2002 reelection campaign by Congressman Bob Riley of Ashland, Clay County, in a very close election that featured a malfunctioning voting machine and charges of vote tampering that favored Riley. Siegelman, however, decided not to call for a recount. In May 2004, he was indicted for rigging bids for state contracts, charges that were later dropped for lack of evidence. The following year in October, however, Siegelman was handed an indictment for bribery and mail and wire fraud, principally for allegedly accepting $500,000 for the lottery campaign from HealthSouth director Richard Scrushy in exchange for placing Scrushy on a state hospital regulatory board that oversaw the later-defunct HealthSouth. Siegelman was convicted of only seven of 32 charges and sentenced to approximately seven years and four months in prison in June 2007. Scrushy, for his part, received a prison sentence of six years and 10 months.

Siegelman Supporter in Birmingham

The bribery and fraud case was complicated by claims made by Siegelman, his supporters, and objective observers, that the charges were improperly pushed by officials in the administration of Pres. George W. Bush. Some claim Siegelman’s political opponents aimed to prevent him from challenging Riley in 2006. The case also prompted an investigation by the U.S. House of Representative Judiciary Committee. Siegelman was released from prison in March 2008 by a federal appeals court but was re-tried in 2009 and his conviction upheld. In June 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court rejected appeals by Siegelman and Scrushy, and in August 2012 Siegelman was sentenced to 78 months in prison. In 2015, dozens of attorneys general and other officials from both parties signed a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court calling for an investigation into his prosecution. Siegelman was released from prison on February 8, 2017, and remained on probation until June 2019. In 2020, he published a book, Stealing Our Democracy: How the Political Assassination of a Governor Threatens Our Nation, detailing his ordeal and discussing reforms needed in the U.S. justice system. In late 2020, the disciplinary committee of the Alabama State Bar voted unanimously to reinstate Siegelman’s law license; it had been revoked after his 2012 conviction.

Siegelman Supporter in Birmingham

The bribery and fraud case was complicated by claims made by Siegelman, his supporters, and objective observers, that the charges were improperly pushed by officials in the administration of Pres. George W. Bush. Some claim Siegelman’s political opponents aimed to prevent him from challenging Riley in 2006. The case also prompted an investigation by the U.S. House of Representative Judiciary Committee. Siegelman was released from prison in March 2008 by a federal appeals court but was re-tried in 2009 and his conviction upheld. In June 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court rejected appeals by Siegelman and Scrushy, and in August 2012 Siegelman was sentenced to 78 months in prison. In 2015, dozens of attorneys general and other officials from both parties signed a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court calling for an investigation into his prosecution. Siegelman was released from prison on February 8, 2017, and remained on probation until June 2019. In 2020, he published a book, Stealing Our Democracy: How the Political Assassination of a Governor Threatens Our Nation, detailing his ordeal and discussing reforms needed in the U.S. justice system. In late 2020, the disciplinary committee of the Alabama State Bar voted unanimously to reinstate Siegelman’s law license; it had been revoked after his 2012 conviction.