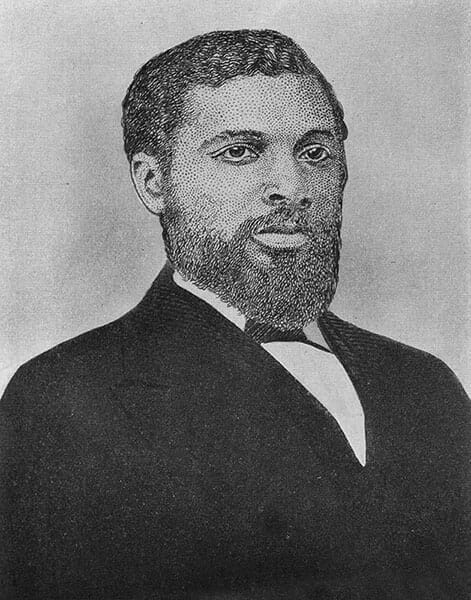

James T. Rapier

James Thomas Rapier (1837-1883) was one of three African American Republican congressmen from Alabama during Reconstruction and fought for passage of the Civil Rights Bill of 1875. Educated in Canada, he returned to his home state, overcame death threats from the Ku Klux Klan, and became a leading figure in the Alabama Republican Party. He was also a teacher, land owner, lawyer, journalist, civic leader, and labor organizer and also served in many official capacities, such as commissioner to the World’s Fair in Paris, France, and the Vienna Exposition in Austria, secretary of the Alabama Equal Rights League, federal internal revenue assessor, and notary public.

Rapier, James T.

Rapier was born in Florence, Lauderdale County, on November 13, 1837, to John H. and Susan Rapier. He had three older brothers. His father was emancipated in 1829 and became a prosperous barber. His mother born into a free black family in Baltimore, Maryland; she died in 1841 in childbirth. In 1842, Rapier and his brother John Jr. moved to Nashville, Tennessee, with their paternal grandmother, Sally Thomas, who worked as a cleaning woman. From 1847 to 1853, Rapier attended a school for African American children, where he learned to read and write. Rapier then moved with his father’s half-brother Henry Thomas to a community established by formerly enslaved people who had escaped in Buxton, Ontario, Canada, where he attended the Buxton Mission School. He studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and the Bible. Rapier experienced a religious conversion and became devoted to supporting civil rights.

Rapier, James T.

Rapier was born in Florence, Lauderdale County, on November 13, 1837, to John H. and Susan Rapier. He had three older brothers. His father was emancipated in 1829 and became a prosperous barber. His mother born into a free black family in Baltimore, Maryland; she died in 1841 in childbirth. In 1842, Rapier and his brother John Jr. moved to Nashville, Tennessee, with their paternal grandmother, Sally Thomas, who worked as a cleaning woman. From 1847 to 1853, Rapier attended a school for African American children, where he learned to read and write. Rapier then moved with his father’s half-brother Henry Thomas to a community established by formerly enslaved people who had escaped in Buxton, Ontario, Canada, where he attended the Buxton Mission School. He studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and the Bible. Rapier experienced a religious conversion and became devoted to supporting civil rights.

In 1856, Rapier attended a normal school (a training school for teachers) in Toronto, Canada, where he earned a teaching degree. The following year, he attended the University of Glasgow in Scotland and Montreal College, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar. He worked as a school instructor in Buxton until 1864, when he relocated to Nashville, Tennessee, and briefly attended Franklin University. He reported for a northern newspaper and purchased 200 acres of land in Maury County, Tennessee, where he became a successful cotton planter. In 1865, Rapier began his political career with a keynote address at the Tennessee Negro Suffrage Convention in Nashville.

The restoration of former Confederates to Tennessee’s state government and the need to care for his ill father prompted him to return to Florence in 1866. Rapier rented 550 acres of farmland on Seven Mile Island, which splits the Tennessee River west of Tuscumbia, where he hired African American tenant farmers and financed low-interest loans for sharecroppers. In March 1867, Rapier served as vice chairman of the Alabama Republican Convention (his father was elected as a county representative) and was the only African American delegate from the Forty-third District to the Alabama Constitutional Convention in Montgomery.

In 1868, the Ku Klux Klan forced Rapier to flee his home for a boarding house in Montgomery, where he remained for one year. It would be the first of several confrontations with the Klan. He later attended the founding convention of the National Negro Labor Union (NNLU) in Washington, D.C., and was chosen as the organization’s vice president in 1870. The NNLU was founded in 1869 to initiate a plan to ease financial burdens on freedmen farmers. He was the first African American to be nominated as Alabama secretary of state but lost the election. The following year, he opened an Alabama branch of the NNLU and served as president and executive chairman.

In 1872, Rapier won the Republication nomination for Alabama’s Second District. He defeated Confederate veteran and future governor William C. Oates in the general election to become Alabama’s second African American Republican representative and member of the Forty-third U. S. Congress, replacing Charles Waldron Buckley. He owned and operated the Montgomery Republican State Sentinel, which was Alabama’s first African American-owned and -operated news source; it promoted the Republican Party, freedmen’s rights, and the reelection of Pres. Ulysses S. Grant. On January 5, 1874, Rapier introduced legislation that designated Montgomery as a federal customs collection site. Signed into law that June, the Montgomery Port Bill was perhaps Rapier’s greatest legislative achievement, and it significantly contributed to the city’s economic growth. While in Congress, Rapier served on the Committee on Education and Labor, voted to regulate the railroads, and supported increasing currency circulation. He also advocated for the Civil Rights Bill of 1875, which guaranteed equal access to public accommodations for all individuals; although it passed that year, it was declared unconstitutional in 1883. Rapier also proposed the creation of a land bureau to help freedmen settle Western lands, especially in Kansas, and sought $5 million for southern schools.

In July 1874, Rapier launched an aggressive campaign for reelection in a hostile atmosphere filled with racial violence and Ku Klux Klan intimidation. Confronted with stolen and destroyed ballot boxes, bribery, fraudulent vote counts, armed mobs, and threats of murder, he lost the general election to former Confederate Army Major Jeremiah Williams. In 1876, Rapier relocated to Lowndes County to challenge incumbent African American representative Jeremiah Haralson for the newly redrawn Fourth District Congressional seat. A split among Republican voters, however, allowed Democrat Charles Shelley to win the election with only 38 percent of the vote.

In June 1878, Rapier was appointed as a collector for the Internal Revenue Service in Alabama’s Second District and fought Democratic attempts to remove him in 1882 and 1883. He then became a labor organizer, encouraged the emigration of freedmen west of the Mississippi River, and purchased land in Wabaunsee County, Kansas, to establish an African American community. Rapier’s health steadily declined in the 1880s, but he served as a disbursing officer for a federal building in Montgomery before his death from pulmonary tuberculosis on May 31, 1883. He died nearly penniless after expending his fortune on African American schools, churches, and emigration projects.

He was eulogized by the Florence Gazette and by the Huntsville Gazette for his talents and character. Rapier was buried among relatives in the Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri, and in 2007, was inducted into the Florence Walk of Honor and honored with a historical marker in River Heritage Park.

Additional Resources

Bailey, Richard. They Too Call Alabama Home: African American Profiles, 1800-1999. Montgomery: Pyramid Publishing, 1999.

Feldman, Eugene. Black Power in Old Alabama: The Life and Stirring Times of James T. Rapier, Afro-American Congressman from Alabama, 1839-1883. Chicago: Museum of African American History, 1968.

———. “James T. Rapier: Negro Congressman from Alabama.” Phylon Quarterly 19 (4th Quarter, 1958): 417-423.

Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Freeman, Thomas J. The Life of James T. Rapier. M. A. Thesis, Auburn University, 1959.

Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. Papers: In the Rapier Family Papers, 1836-1883.

Rabinowitz, Howard, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

Schweninger, Loren. James T. Rapier and Reconstruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

———. “James Rapier and the Negro Labor Movement, 1869-1872,” Alabama Review 28 (July 1975): 185-201.