Richard Arrington Jr.

Richard Arrington

Richard Arrington Jr. (1934- ) was the first African American mayor of Birmingham, Jefferson County, and served five terms in that office from 1979 to 1999. He has been so far the longest serving mayor in the city’s history and its only five-term mayor. Under his tenure, Birmingham went from a racially divided city dependent on the steel industry to an economically and culturally diverse hub of the southeastern United States. Arrington’s low-key style and business alliances helped transform the city’s image and its economy.

Richard Arrington

Richard Arrington Jr. (1934- ) was the first African American mayor of Birmingham, Jefferson County, and served five terms in that office from 1979 to 1999. He has been so far the longest serving mayor in the city’s history and its only five-term mayor. Under his tenure, Birmingham went from a racially divided city dependent on the steel industry to an economically and culturally diverse hub of the southeastern United States. Arrington’s low-key style and business alliances helped transform the city’s image and its economy.

Arrington was born on October 19, 1934, in the west Alabama town of Livingston, Sumter County, to Richard Sr. and Mary Arrington, who had one other son, James. Arrington’s father worked as a sharecropper during the early part of Arrington’s life. When Arrington was five, his father moved the family to Fairfield to take a job with the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) and also worked part-time as a brick mason to supplement his income at TCI. Arrington credits his industrious drive and strong work ethic to his father.

Arrington excelled at Fairfield Industrial High School in Jefferson County and graduated at the age of 16. He then enrolled in Fairfield’s historically black Miles College and majored in biology. He continued to be an exemplary student and was an officer in the honor society and president of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. At the age of 18, Arrington married Barbara Jean Watts, whom he had met in high school, and the couple would have five children. In 1955, Arrington graduated with honors and entered graduate school at the University of Detroit. Receiving his master’s degree in zoology two years later, Arrington returned to Miles College to teach science. Arrington left Miles College in 1963 and he then enrolled in a doctoral program in biology at the University of Oklahoma because there were no similar graduate opportunities for blacks in Alabama. He received the Ortenburger Award for his exemplary microbiology research and completed his doctorate in 1966. After graduation, Arrington again returned to Miles College as an academic dean, a position which he held until 1970.

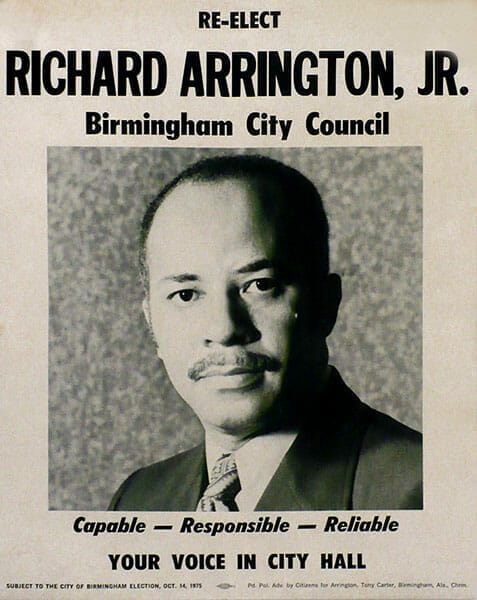

Richard Arrington 1975 Campaign Poster

Arrington entered public service in Birmingham to give the poor a voice in city government and local politics. He also wanted to provide solutions to economic development and urban blight in Birmingham. During his four-term tenure on the city council (from 1971 to 1979) Arrington focused his efforts on economic growth, education, and crime.

Richard Arrington 1975 Campaign Poster

Arrington entered public service in Birmingham to give the poor a voice in city government and local politics. He also wanted to provide solutions to economic development and urban blight in Birmingham. During his four-term tenure on the city council (from 1971 to 1979) Arrington focused his efforts on economic growth, education, and crime.

Despite progress made in civil rights in Birmingham during the 1960s, racial problems continued into the 1970s, with notable instances of police brutality against African Americans. One particular instance was the unjustified shooting death of Bonita Carter, an unarmed black woman who was misidentified as a suspect in an armed robbery. After this incident, Arrington often discussed police brutality in city council meetings to shed light on this problem. Incumbent mayor David Vann failed to ease racial tensions between the city’s black leaders and the police department and between the black and white communities in the aftermath of the incident. In response, black leaders began a boycott of Birmingham businesses that cost the city tax revenue. The city’s black leaders also looked for someone to represent them and convinced Arrington to run for mayor in 1979.

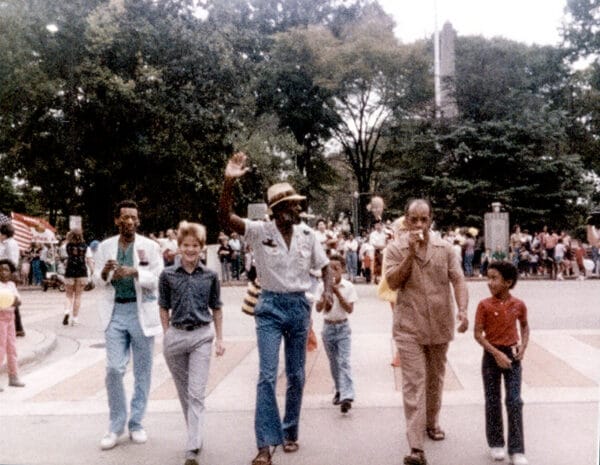

Richard Arrington Jr. and Fob James

Arrington did not particularly like campaigning, but garnered broad support among blacks and just enough support among whites because of his community efforts and reforms as a member of the city council. Furthermore, Arrington received the endorsement of Birmingham’s two major newspapers——the Birmingham News and the Birmingham Post-Herald——and an important endorsement from Alabama lieutenant governor George McMillan, a Birmingham native. Arrington gained these endorsements because he calmed the fears of white liberals and had also built business relationships with some whites in the business community. Arrington also reviewed historical voting patterns and polling data and determined that he would need at least 10 percent of the white vote, because white voters outnumbered blacks by nearly 14,000. Arrington ran a somewhat race-neutral campaign, asking voters to focus on each candidate’s qualifications. Other candidates in the race included John Katapodis, a white former Birmingham school board employee and city councilman; Larry Langford, a black city councilman; and Frank Parsons, a white attorney. In the election, incumbent Vann finished fourth, a referendum on his mishandling of race relations. The resulting run-off between Arrington and Parsons featured more racial pandering as former mayor George Seibels Jr. took out a full-page newspaper advertisement accusing Arrington of inflaming racial fears to encourage more black support. Voter turn-out was large, and Arrington eked out a victory by less than 3 percent, receiving about 12 percent of the white vote despite the negative tone of the campaign. He was sworn in on November 13, 1979, and would win four more terms, retiring in 1999.

Richard Arrington Jr. and Fob James

Arrington did not particularly like campaigning, but garnered broad support among blacks and just enough support among whites because of his community efforts and reforms as a member of the city council. Furthermore, Arrington received the endorsement of Birmingham’s two major newspapers——the Birmingham News and the Birmingham Post-Herald——and an important endorsement from Alabama lieutenant governor George McMillan, a Birmingham native. Arrington gained these endorsements because he calmed the fears of white liberals and had also built business relationships with some whites in the business community. Arrington also reviewed historical voting patterns and polling data and determined that he would need at least 10 percent of the white vote, because white voters outnumbered blacks by nearly 14,000. Arrington ran a somewhat race-neutral campaign, asking voters to focus on each candidate’s qualifications. Other candidates in the race included John Katapodis, a white former Birmingham school board employee and city councilman; Larry Langford, a black city councilman; and Frank Parsons, a white attorney. In the election, incumbent Vann finished fourth, a referendum on his mishandling of race relations. The resulting run-off between Arrington and Parsons featured more racial pandering as former mayor George Seibels Jr. took out a full-page newspaper advertisement accusing Arrington of inflaming racial fears to encourage more black support. Voter turn-out was large, and Arrington eked out a victory by less than 3 percent, receiving about 12 percent of the white vote despite the negative tone of the campaign. He was sworn in on November 13, 1979, and would win four more terms, retiring in 1999.

Richard Arrington and Famous Amos

Birmingham’s downtown area grew under Arrington’s tenure, and his impact on the Birmingham economy was extraordinary in his 20 years as mayor. The city renovated older buildings, such as the “old” Central Library (renamed the Linn-Henley Research Library), and constructed a new one that was named the Central Library; he added a new wing to city hall and built several parking decks. Arrington also led the drive for the establishment of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. In addition, Alabama Power Company constructed a large complex and located its headquarters in the city, the U.S. Department of Justice built the Hugo L. Black Federal Courthouse, the University of Alabama at Birmingham made extensive improvements, and New York Life Insurance Company completed a new building, as well. Furthermore, Birmingham added a record number of jobs, had record low unemployment, and possessed the strongest tax base in Alabama. On his watch, the city’s once steel-dependent economy became one of the most diverse in the region, boasting growth in banking and health care in particular. The city also created the only $100-million endowment fund in the Southeast.

Richard Arrington and Famous Amos

Birmingham’s downtown area grew under Arrington’s tenure, and his impact on the Birmingham economy was extraordinary in his 20 years as mayor. The city renovated older buildings, such as the “old” Central Library (renamed the Linn-Henley Research Library), and constructed a new one that was named the Central Library; he added a new wing to city hall and built several parking decks. Arrington also led the drive for the establishment of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. In addition, Alabama Power Company constructed a large complex and located its headquarters in the city, the U.S. Department of Justice built the Hugo L. Black Federal Courthouse, the University of Alabama at Birmingham made extensive improvements, and New York Life Insurance Company completed a new building, as well. Furthermore, Birmingham added a record number of jobs, had record low unemployment, and possessed the strongest tax base in Alabama. On his watch, the city’s once steel-dependent economy became one of the most diverse in the region, boasting growth in banking and health care in particular. The city also created the only $100-million endowment fund in the Southeast.

Arrington worked tirelessly to overcome Birmingham’s history of racial tension and discrimination in awarding city jobs and contracts. He used city-wide affirmative action plans in issuing contracts and hiring of city employees. By the mid-1990s, Arrington had integrated the city’s payroll, with blacks holding nearly half of all positions. He also appointed more blacks to head city departments, which, by 1995 were split evenly amongst blacks and whites. More African American-owned firms were awarded a larger share of city contracts.

Arrington’s tenure as mayor was not without controversy, and he faced much scrutiny from his critics. Individuals in both the black and white communities questioned whether his administration’s awarding of city contracts and its hiring practices were not racially motivated and forms of cronyism. Also, the influential Jefferson County Citizens Coalition (JCCC), a grassroots political organization Arrington founded in 1977 to raise funds and to mobilize and influence black voters in central Alabama, was criticized for having too much influence.

In 1992, the Justice Department charged Arrington with accepting a kickback for construction related to the Civil Rights Institute and jailed him for one day for refusing to cooperate with the investigation. Arrington refused to release five years’ of his appointment logs and other documents. A master politician, Arrington led a march from Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, an iconic site of the civil rights movement, to turn himself in to the authorities, rallying African Americans to his defense. Eventually, Arrington cooperated and the appointment logs and other documents were released. Tarlee W. Brown, Arrington’s former business partner from Atlanta, Georgia, pleaded guilty to defrauding the city and paying the mayor $5,000 for city architectural work. Arrington was upset by these charges and believed it was a tactic to affect the mayoral race. In 1993, the Justice Department finally dropped the charges against Arrington. The improprieties alleged in this incident and its subsequent fallout did not affect his popularity with Birmingham voters. Most in Birmingham’s black population believe this was an effort to smear an outspoken African American mayor while the white community was split over the corruption allegations.

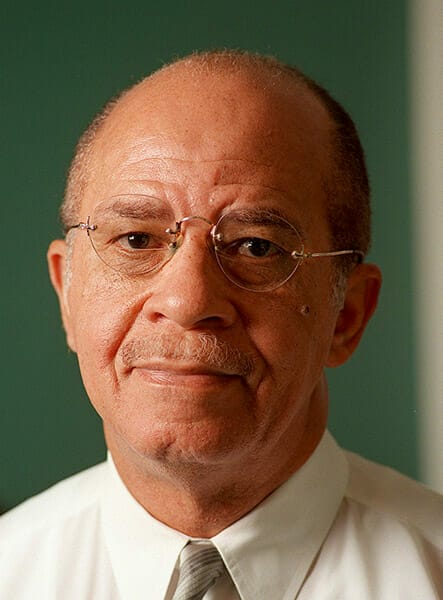

Richard Arrington, 2017

Arrington stated publicly in 1999 that he would not seek a sixth term that year and planned to retire while still in office so that he could hand-pick city council president William Bell as his successor. Despite this political advantage, Bell lost in an upset to Bernard Kincaid, perhaps a sign that Arrington’s influence was waning. That same year, Arrington founded an educational consulting firm and political action committee, JENNRO, to help promote his agenda for improving education. Arrington supported incumbent Rep. Earl Hilliard in 2002, but Hilliard lost to newcomer Artur Davis. He would later endorse another Davis opponent, Commissioner of the Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries Ron Sparks, in the 2010 Democratic gubernatorial primary. In 2008, he released a memoir, There Is Hope for This World. Also, Arrington helped form the New Jefferson County Citizens Coalition, but it has had only minor success influencing recent city elections. Since Arrington retired from public office, he has taught biology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and is on the faculty at Miles College. He continues to hold substantial influence in the community. He was inducted into the Alabama Academy of Honor in 2015, and in 2017, Arrington received the Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Richard Arrington, 2017

Arrington stated publicly in 1999 that he would not seek a sixth term that year and planned to retire while still in office so that he could hand-pick city council president William Bell as his successor. Despite this political advantage, Bell lost in an upset to Bernard Kincaid, perhaps a sign that Arrington’s influence was waning. That same year, Arrington founded an educational consulting firm and political action committee, JENNRO, to help promote his agenda for improving education. Arrington supported incumbent Rep. Earl Hilliard in 2002, but Hilliard lost to newcomer Artur Davis. He would later endorse another Davis opponent, Commissioner of the Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries Ron Sparks, in the 2010 Democratic gubernatorial primary. In 2008, he released a memoir, There Is Hope for This World. Also, Arrington helped form the New Jefferson County Citizens Coalition, but it has had only minor success influencing recent city elections. Since Arrington retired from public office, he has taught biology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and is on the faculty at Miles College. He continues to hold substantial influence in the community. He was inducted into the Alabama Academy of Honor in 2015, and in 2017, Arrington received the Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Further Reading

- Arrington, Richard. There’s Hope for the World: The Memoir of Birmingham, Alabama’s First African American Mayor. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Franklin, Jimmie Lewis. Back to Birmingham: Richard Arrington, Jr., and His Times. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989.

- Thompson, J. Phillip, III. Double Trouble: Black Mayors, Black Communities, and the Call for a Deep Democracy (Transgressing Boundaries). New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.