Episcopal Church in Alabama

Holy Cross Episcopal Church

Although only a small proportion of Alabamians have belonged to the Episcopal Church, it has been the preferred church of the planters, industrialists, and the people who have shaped the state. Since the establishment of its first congregations in 1828, membership in the Episcopal Church in Alabama has remained small, usually about 1 percent of the total population. Many prominent early ninteenth-century Alabamians were Episcopalians, including Gov. John Gayle, Congressman William Lowndes Yancey, author Octavia Walton Le Vert, and lawyer and newspaper editor John Withers Clay. Jefferson Davis (a Baptist) and his Episcopalian wife, Varina, regularly worshiped at St. John’s in Montgomery. In the twentieth century, prominent Alabama Episcopalians have included actress Tallulah Bankhead, novelist Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, and four governors: Charles Henderson, Thomas Kilby, Gordon Persons, and Forrest “Fob” James.

Holy Cross Episcopal Church

Although only a small proportion of Alabamians have belonged to the Episcopal Church, it has been the preferred church of the planters, industrialists, and the people who have shaped the state. Since the establishment of its first congregations in 1828, membership in the Episcopal Church in Alabama has remained small, usually about 1 percent of the total population. Many prominent early ninteenth-century Alabamians were Episcopalians, including Gov. John Gayle, Congressman William Lowndes Yancey, author Octavia Walton Le Vert, and lawyer and newspaper editor John Withers Clay. Jefferson Davis (a Baptist) and his Episcopalian wife, Varina, regularly worshiped at St. John’s in Montgomery. In the twentieth century, prominent Alabama Episcopalians have included actress Tallulah Bankhead, novelist Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, and four governors: Charles Henderson, Thomas Kilby, Gordon Persons, and Forrest “Fob” James.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

Until the late nineteenth century, Alabama’s Episcopal churches were mainly located in Mobile, the Black Belt, and the Tennessee Valley. In Alabama, as elsewhere in the United States, politically, economically, and socially prominent people tended to be Episcopalian. Approximately two-thirds of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were members of the Episcopal Church, and more U.S. presidents have belonged to the Church than to any other denomination. Because the most powerful figures during the nineteenth century in the South tended to be plantation owners, the Episcopal Church has been described as “the slaveholders’ church” during that period.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

Until the late nineteenth century, Alabama’s Episcopal churches were mainly located in Mobile, the Black Belt, and the Tennessee Valley. In Alabama, as elsewhere in the United States, politically, economically, and socially prominent people tended to be Episcopalian. Approximately two-thirds of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were members of the Episcopal Church, and more U.S. presidents have belonged to the Church than to any other denomination. Because the most powerful figures during the nineteenth century in the South tended to be plantation owners, the Episcopal Church has been described as “the slaveholders’ church” during that period.

Alabama’s first two Episcopal congregations were organized in 1828: Christ Church in Tuscaloosa, in January of that year, and, a few weeks later in February, Christ Church in Mobile. Since 1822, however, the members of the Mobile church had been part of a Protestant “union church” in which Methodists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians worshiped together. The Episcopal Church developed from the remnants of the Church of England, which, prior to 1776, had been concentrated in the Middle Atlantic states and the upper South. Many of the clergy and some of the lay members of Church of England parishes in America fled during and after the Revolutionary War. Those who remained organized the Episcopal Church at a meeting in Philadelphia in 1785. The Diocese of Alabama was organized and admitted to the Episcopal Church in January 1830, when Thomas Brownell, Bishop of Connecticut, presided at the first diocesan convention in Mobile. He was followed by Jackson Kemper (missionary bishop of the northwest), Leonidas Polk (later a general in the Confederate army), and James H. Otey (the first bishop of Tennessee).

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

Although a native of Virginia, Nicholas Hamner Cobbs was rector of St. Paul’s Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, when he was elected Alabama’s first diocesan bishop at St. Paul’s Church in Greensboro, Hale County, in 1844. At that time, there were only 18 Episcopal churches in Alabama and fewer than 500 total active members. At the time of his death in 1861, the diocese had 39 parishes and almost 1,700 communicants. Cobbs vowed to visit every Episcopalian family in the state and established the first African American Episcopal congregation. There is no evidence that Cobbs was pro-abolition, however, and the vast majority of Episcopalians in the United States were either pro-slavery or silent on the topic. Thus, unlike the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, the membership of the Episcopal Church was not divided over the issue.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

Although a native of Virginia, Nicholas Hamner Cobbs was rector of St. Paul’s Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, when he was elected Alabama’s first diocesan bishop at St. Paul’s Church in Greensboro, Hale County, in 1844. At that time, there were only 18 Episcopal churches in Alabama and fewer than 500 total active members. At the time of his death in 1861, the diocese had 39 parishes and almost 1,700 communicants. Cobbs vowed to visit every Episcopalian family in the state and established the first African American Episcopal congregation. There is no evidence that Cobbs was pro-abolition, however, and the vast majority of Episcopalians in the United States were either pro-slavery or silent on the topic. Thus, unlike the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, the membership of the Episcopal Church was not divided over the issue.

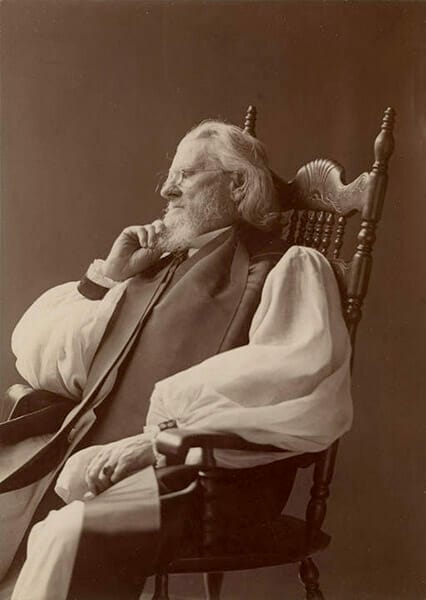

Richard Hooker Wilmer

Cobbs strongly opposed secession and was said to have prayed that he would not live to see Alabama secede from the United States. Shortly before noon on the day that the state of Alabama voted to secede from the Union, Cobbs died. A few months later, the bishops of Episcopal churches in the Confederate states met in Montgomery to organize the Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America and discuss Alabama’s need for a new bishop. In the fall of 1861, Richard Hooker Wilmer was elected the second Bishop of Alabama, and he led the diocese until his death in 1900. Wilmer, an ardent supporter of secession, was the only bishop elected and consecrated in the Confederate Episcopal Church.

Richard Hooker Wilmer

Cobbs strongly opposed secession and was said to have prayed that he would not live to see Alabama secede from the United States. Shortly before noon on the day that the state of Alabama voted to secede from the Union, Cobbs died. A few months later, the bishops of Episcopal churches in the Confederate states met in Montgomery to organize the Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America and discuss Alabama’s need for a new bishop. In the fall of 1861, Richard Hooker Wilmer was elected the second Bishop of Alabama, and he led the diocese until his death in 1900. Wilmer, an ardent supporter of secession, was the only bishop elected and consecrated in the Confederate Episcopal Church.

During the war, Wilmer founded an order of deaconesses, a group of women who were chosen for service by the bishop, to care for Confederate widows and orphans and established a home for orphans. The order lapsed in the early twentieth century but their work is continued by Wilmer Hall Children’s Home in Mobile. During Military Reconstruction, Wilmer ordered his clergy not to pray for the U.S. president, so Alabama’s military governor, Wager Swayne, closed all the Episcopal churches in Alabama until Pres. Andrew Johnson rescinded that order a year later.

Prior to the Civil War, most of Alabama’s Episcopal churches included Black, mostly enslaved, worshipers. The oldest black Episcopal Church is Good Shepherd in Mobile, founded in 1854. The second black Episcopal Church in Alabama was founded in 1892 by a group of black Episcopalians who sought and received permission from Bishop Wilmer to found St. Mark’s parish and industrial school. After the Civil War, most Blacks left the Episcopal Church and other predominantly white denominations.

In the 1870s, as Alabama’s economy shifted from plantation agriculture in the Black Belt region to industrialization around Birmingham, the Episcopal Church in the state saw a related shift in membership population centers. Birmingham’s first church, the Church of the Advent, was founded in 1871 on a lot set aside for it by the Elyton Land Company; in only a year’s time, it had become the largest parish in the diocese (and is today one of the largest in the national Episcopal Church). In 1887, members of the Church of the Advent helped James Van Hoose, an Episcopal deacon and mayor of Birmingham, organize a Sunday School that soon became St. Mary’s-on-the-Highlands Episcopal Church.

Wilmer died on June 14, 1900, with the distinction of being the longest serving bishop in the Episcopal Church. Toward the end of his tenure, he was briefly assisted by Henry Melville Jackson, another Virginia priest who was elected to serve as Alabama’s assistant bishop. Jackson, however, was accused of alcohol abuse, debt, and dereliction of duty and was asked to step down. After Wilmer’s death, the Diocese of Alabama elected their first Alabama-born bishop, Robert Barnwell, the rector of St. Paul’s in Selma. Barnwell died of a ruptured appendix just two years later.

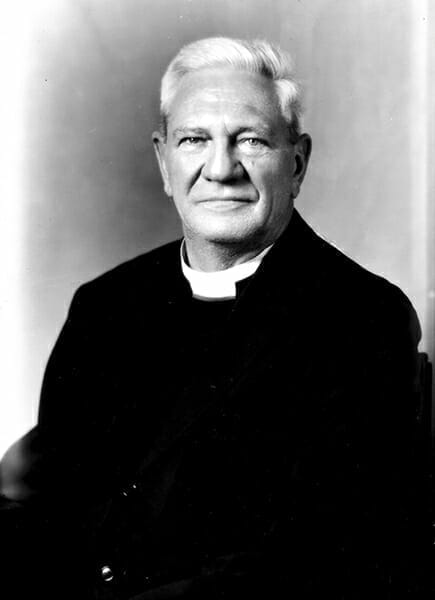

Edgar Gardner Murphy

Edgar Gardner Murphy, who became rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery in 1898, would become one of the most distinguished priests to serve in the Diocese of Alabama. Murphy was a tireless advocate for reforming education and child labor laws and earned the praise of Pres. Theodore Roosevelt.

Edgar Gardner Murphy

Edgar Gardner Murphy, who became rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery in 1898, would become one of the most distinguished priests to serve in the Diocese of Alabama. Murphy was a tireless advocate for reforming education and child labor laws and earned the praise of Pres. Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1902, the diocese chose as its new bishop Charles Minnigerode Beckwith, the General Missioner of the Diocese of Texas. Beckwith was an avid outdoorsman. He built a hunting lodge near Fairhope, which subsequently became Beckwith Lodge, the retreat center of the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast. Beckwith, however, had an abrasive and high-handed manner and was involved in an escalating series of conflicts with local clergy. In 1922, facing ouster, Beckwith turned over his authority to his newly elected bishop coadjutor, (a bishop elected or appointed to follow the current diocesan bishop upon the incumbent’s death or retirement) William George McDowell. Beckwith remained Bishop of Alabama in name only until his death in 1928.

Formerly rector of Holy Innocents in Auburn, McDowell was involved in many social and political issues of the day. For example, McDowell and Birmingham Presbyterian pastor Henry Edmonds worked behind the scenes as advocates for the defendants in the infamous Scottsboro Trials. In 1938, he ran unsuccessfully for the position of Presiding Bishop of the national Episcopal Church, spurred on, perhaps, by the success of Selma native and former rector of Birmingham’s Church of the Advent John Gardner Murray, who had been elected Presiding Bishop more than a decade earlier. In 1938, McDowell fell ill while visiting Mobile’s Trinity Church and died of pneumonia at the Mobile Infirmary on March 20.

In the early twentieth century, Alabama’s Episcopalians became involved in a number of social issues. Birmingham priest Carl Henckell (who had studied dentistry at Syracuse University in New York State) served small parishes (mostly now defunct) in Birmingham’s working-class neighborhoods, such as Christ Church (Avondale), and Good Shepherd (East Lake). Henckell also was instrumental in founding Birmingham’s Children’s Hospital. Alabama’s first child labor inspector, Augusta Bening Martin, founded the House of Happiness, an outreach to the poor whites of Sand Mountain, near Scottsboro in 1923. In 1929, McDowell launched an effort to reach the Poarch Band of Creek Indians near Atmore, overseeing construction of two churches among them. In 1939, the federal Works Progress Administration built a Black community center in Selma, largely as a result of a campaign by Edward Gamble, the rector of St. Paul’s in Selma.

In 1938, Charles Colcock Jones Carpenter, rector of the Church of the Advent, was elected Alabama’s sixth bishop; he presided during the “baby boom” that followed World War II, a time when almost every religious group in the United States was experiencing growth. During Carpenter’s tenure, a number of parishes were added in the Birmingham area, Huntsville, Tuscaloosa, and Tuskegee, among others. Among Carpenter’s most significant accomplishments was the founding of Camp McDowell, near Jasper. Camp McDowell runs summer camps for young people and is available throughout the year for a wide variety of functions.

Charles Carpenter

Carpenter was the leader of Alabama’s Episcopal Church during the civil rights movement, and his actions are still controversial. On two very significant occasions, Carpenter took positions that painted himself and Alabama’s Episcopalians as reactionaries. When Martin Luther King Jr. announced plans to demonstrate in Birmingham during Holy Week in 1963 (what became known as the Birmingham Campaign), Carpenter and six other religious leaders urged King to wait. King reproached the men in his devastating “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Two years later, when King organized the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, Carpenter did everything in his power to prevent Episcopal clergy from participating in the march. In spite of his opposition to the civil rights movement, Carpenter had good relationships with Black clergy in his diocese, facilitated meetings between Birmingham’s Black and white leadership, and oversaw the integration of Camp McDowell.

Charles Carpenter

Carpenter was the leader of Alabama’s Episcopal Church during the civil rights movement, and his actions are still controversial. On two very significant occasions, Carpenter took positions that painted himself and Alabama’s Episcopalians as reactionaries. When Martin Luther King Jr. announced plans to demonstrate in Birmingham during Holy Week in 1963 (what became known as the Birmingham Campaign), Carpenter and six other religious leaders urged King to wait. King reproached the men in his devastating “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Two years later, when King organized the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, Carpenter did everything in his power to prevent Episcopal clergy from participating in the march. In spite of his opposition to the civil rights movement, Carpenter had good relationships with Black clergy in his diocese, facilitated meetings between Birmingham’s Black and white leadership, and oversaw the integration of Camp McDowell.

Carpenter retired at the end of 1968 and died less than a year later. George Murray, bishop coadjutor of Alabama, became the seventh bishop of Alabama. More liberal than his predecessor, Murray urged Alabama Episcopalians to find ways to participate in Pres. Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” social welfare programs. Murray’s most significant achievement was to create a new diocese, a project that had been discussed in the Diocese of Alabama almost from the very beginning. In 1970, the Diocese of the Central Gulf coast was established to oversee the lower third of Alabama (below Montgomery) and the Florida panhandle. Murray chose to step down as the seventh Bishop of Alabama and become the first Bishop of the Central Gulf Coast. The Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast has had three bishops since 1970—Murray, Charles Duvall, and Philip Duncan—and the Diocese of Alabama has had four diocesan bishops: Furman C. Stough, Robert O. Miller, Henry N. Parsley Jr., and John McKee Sloan. Both Stough and Parsley were nominated for Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church but were defeated.

Christ Church in Mobile

In the last 40 years, the Episcopal Church in the United States has begun to ordain women to the offices of priest and bishop, completely re-written the Book of Common Prayer, and seen the election of its first openly gay bishop in New Hampshire. Neither prayer book revision nor the ordination of women caused much controversy in Alabama; many parishes are now led by women clergy. But the movement for the full inclusion of gays and lesbians in the church has been implicated in splits in several of Alabama’s Episcopal churches, including Christ Church in Mobile and Ascension and Christ the Redeemer (now defunct) in Montgomery. In the same period, both the Diocese of Alabama and the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast have worked to build housing for the elderly and establish relationships with Anglican dioceses in the developing world. Both have also re-designated existing churches to serve as cathedrals, a project first envisioned by Bishop Cobbs before the Civil War.

Christ Church in Mobile

In the last 40 years, the Episcopal Church in the United States has begun to ordain women to the offices of priest and bishop, completely re-written the Book of Common Prayer, and seen the election of its first openly gay bishop in New Hampshire. Neither prayer book revision nor the ordination of women caused much controversy in Alabama; many parishes are now led by women clergy. But the movement for the full inclusion of gays and lesbians in the church has been implicated in splits in several of Alabama’s Episcopal churches, including Christ Church in Mobile and Ascension and Christ the Redeemer (now defunct) in Montgomery. In the same period, both the Diocese of Alabama and the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast have worked to build housing for the elderly and establish relationships with Anglican dioceses in the developing world. Both have also re-designated existing churches to serve as cathedrals, a project first envisioned by Bishop Cobbs before the Civil War.