Alabama Constitution of 1901

Written primarily to codify white supremacy by disfranchising blacks, the Constitution of 1901 continues to shape Alabama politics in the twenty-first century. The constitution also concentrated power in the state legislature, decreased opportunities for home rule, and established voter requirements that even many white men could not meet, reducing the political influence of the state’s many poor whites.

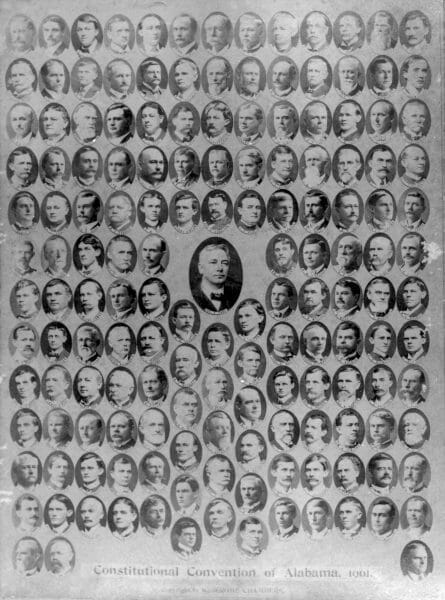

1901 Constitutional Convention

The political developments that led to the Constitution of 1901 originated in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. The Republican-controlled U.S. Congress abolished slavery under the 13th Amendment, granted citizenship to former slaves under the 14th Amendment, and guaranteed them the right to vote with the 15th Amendment. Congress forced the ex-Confederate states to pass constitutions that further articulated these rights for former slaves. When Alabama’s Democratic Party regained control of the state government in the election of 1874, one of its first actions was to overturn Alabama’s Reconstruction Constitution of 1868, which had expanded voting rights among African Americans and poor whites.

1901 Constitutional Convention

The political developments that led to the Constitution of 1901 originated in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. The Republican-controlled U.S. Congress abolished slavery under the 13th Amendment, granted citizenship to former slaves under the 14th Amendment, and guaranteed them the right to vote with the 15th Amendment. Congress forced the ex-Confederate states to pass constitutions that further articulated these rights for former slaves. When Alabama’s Democratic Party regained control of the state government in the election of 1874, one of its first actions was to overturn Alabama’s Reconstruction Constitution of 1868, which had expanded voting rights among African Americans and poor whites.

Alabama Democrats, also referred to as Bourbons, achieved their primary goals of lowering taxes and reducing government spending in the 1875 Constitution. They also forbade the state and municipalities from lending money for internal improvements, eliminated the State Board of Education created in 1868, segregated the state’s public schools, and reduced spending for education. The 1875 constitution did little to alter voting rights, however, because the federal government would have swiftly nullified any document that discriminated against blacks.

Democrats feared losing local and state offices to Republicans, however, so they developed creative ways to reduce the influence of blacks, who overwhelmingly voted for Republicans. For example, Democrats implemented secret ballots that also served as literacy tests because they prevented family members or election officials from reading the ballot for illiterate voters. The 1893 Sayre Act allowed the Alabama governor to appoint election officials and made the voting process difficult for poor and illiterate blacks and whites through small changes to the election system, including listing candidates alphabetically instead of by party and by registering voters only in May, the busiest month for farmers. In addition, the Democrats gerrymandered black votes into single districts, eliminated elected positions in favor of appointments to reduce voters’ influence, and turned to stuffing ballot boxes as a way to ensure political victories. For 20 years, the Bourbons used these methods to control the electoral influence of the Black Belt’s significant black population, and also expanded their use throughout the state in the 1890s to limit the influence of Populist candidates who represented small farmers and laborers.

After they defeated the Populist threat through electoral fraud, Alabama Democrats again turned their attention to the issue of black suffrage. The methods used in the 1870s and 1880s had successfully restricted the number of black voters, but Democratic leaders in the 1890s hoped to eliminate black suffrage completely and found inspiration in the practices of other southern states. Mississippi (1890), South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), and North Carolina (1900) had all disfranchised blacks through new constitutions that implemented some combination of poll taxes, property and education qualifications, and a grandfather clause, in the case of Louisiana. With a new constitution, Alabama lawmakers could also promote industrialization, which had been hindered by limiting government investment in 1875 when the state was largely agrarian.

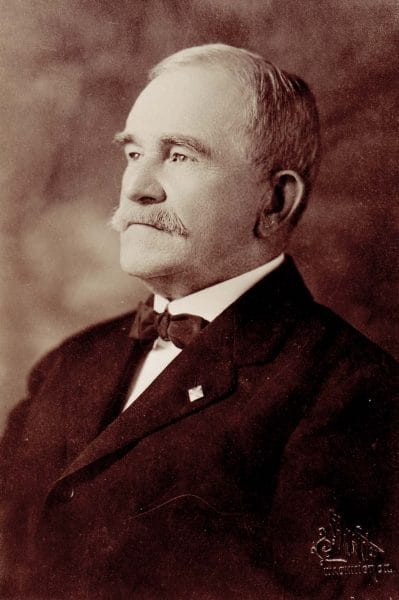

Joseph F. Johnston

In 1901, Alabama’s legislature approved a statewide referendum calling for a constitutional convention. Over the objections of reform-minded former governor Joseph F. Johnston, on April 23 the referendum passed, with the aid of substantial electoral fraud in the Black Belt. The convention’s 155 delegates represented the state, its federal congressional districts, the state Senate, and counties. Delegates, predominantly Democrats, included two governors, two former justices of the Alabama Supreme Court, and several U.S. Representatives, as well as mayors, judges, and lawyers who collectively did little to represent the interests of poor whites and African Americans. None of the delegates were African American.

Joseph F. Johnston

In 1901, Alabama’s legislature approved a statewide referendum calling for a constitutional convention. Over the objections of reform-minded former governor Joseph F. Johnston, on April 23 the referendum passed, with the aid of substantial electoral fraud in the Black Belt. The convention’s 155 delegates represented the state, its federal congressional districts, the state Senate, and counties. Delegates, predominantly Democrats, included two governors, two former justices of the Alabama Supreme Court, and several U.S. Representatives, as well as mayors, judges, and lawyers who collectively did little to represent the interests of poor whites and African Americans. None of the delegates were African American.

The convention assembled on May 21st and elected Anniston delegate John B. Knox president on May 22nd. The convention would be in session until September 3rd, meeting for 82 days and breaking only on Sundays and for the July 4th holiday. In his opening speech, Knox declared to delegates that federally imposed Reconstruction had forced them into action. The convention had been called to disfranchise blacks without disfranchising any whites, which would be achieved by enshrining white supremacy legally in a constitution and eliminating the need for election fraud. Knox further proposed that disfranchising blacks was legitimate if it was done on the basis of their “intellectual and moral condition,” and not because of their race.

Article VIII of the new Constitution, containing Sections 177-196, defined suffrage and election requirements and included both permanent and temporary registration plans. In the permanent plan, applicants had to meet multiple requirements beyond the federal mandate that voters be male and 21 years old. The most onerous provisions were enshrined in Section 181 and included requirements for literacy tests (the ability to read and write an article of the U.S. Constitution) and employment for at least one year and installed stringent property qualifications. In addition, Section 182 disqualified individuals convicted of a variety of minor crimes, such as vagrancy, as well as those alleged to have moral failings or mental deficiencies.

William Calvin Oates

The requirements in Section 181 were difficult for most African Americans and poor white men to meet, but delegates provided three exceptions for the latter group within the temporary registration plan of Section 180. For one year only, from 1902 to 1903, any adult male who proved that he understood the U.S. Constitution, was a veteran of any nineteenth-century American war, or was descended from a veteran, could register to vote, even if he did not fulfill any other requirements. This so-called “grandfather clause,” however, was the constitution’s most controversial section at the time. Because very few blacks had ever been allowed to serve in the military, Stouten H. Dent, William C. Oates, George P. Harrison, and Frank S. White of the suffrage committee believed that the grandfather clause blatantly discriminated against blacks and violated the U.S. Constitution, but they were unable to remove the clause from the suffrage article.

William Calvin Oates

The requirements in Section 181 were difficult for most African Americans and poor white men to meet, but delegates provided three exceptions for the latter group within the temporary registration plan of Section 180. For one year only, from 1902 to 1903, any adult male who proved that he understood the U.S. Constitution, was a veteran of any nineteenth-century American war, or was descended from a veteran, could register to vote, even if he did not fulfill any other requirements. This so-called “grandfather clause,” however, was the constitution’s most controversial section at the time. Because very few blacks had ever been allowed to serve in the military, Stouten H. Dent, William C. Oates, George P. Harrison, and Frank S. White of the suffrage committee believed that the grandfather clause blatantly discriminated against blacks and violated the U.S. Constitution, but they were unable to remove the clause from the suffrage article.

Although the suffrage article explicitly discriminated against black citizens, several delegates believed that they should be able to earn the right to vote. Paternalists such as Oates argued that Alabama needed educated and responsible voters, no matter their race and thus opposed the inclusion of Section 180. Ultimately, the controversial grandfather clause passed because most delegates believed illiterate whites had an inherent understanding of democracy that all blacks lacked.

Although the constitutional convention ensured that all white men could register to vote, most delegates did not view voting as an undeniable right. Section 194 required all voters aged 21 through 45 to pay a cumulative poll tax of $1.50 every year to continue voting, a considerable sum for the state’s many poor farmers and laborers. Individuals who paid another person’s poll tax were guilty of bribery and lost their right to vote. Proceeds from the taxes went to education funding in the respective counties.

Beyond suffrage, delegates discussed other important issues. The public urged the convention to increase the Alabama Railroad Commission’s power to regulate corruption, but Bourbons representing industrial and Black Belt interests ensured that no change occurred. In 1901, public schools already received the largest percentage of the state budget, but Alabamians desired more money for improvements without paying higher taxes. In this instance, the convention kept both promises: It reduced the tax limit and allocated more state funds for education. However, delegates rejected a provision allowing citizens to approve special district taxes, thus depriving schools of a significant source of revenue.

In the weeks leading up to the ratification vote, supporters of the constitution advertised its aim to enshrine white supremacy. Most blacks in the state, including Booker T. Washington, realized that they would be adversely affected and objected through petitions and protests. Former Populists, led by Joseph F. Johnston, also opposed ratification. Despite these objections, the constitution was approved by popular vote on November 11, 1901, with 108,613 votes cast in favor and 81,734 votes against. Historians have largely concluded that its passage was the result of considerable fraud in the Black Belt counties, which were predominantly African American yet overwhelmingly approved the measure.

Many of the convention’s decisions, from suffrage to taxation, have hampered the state, but two in particular continue to impair Alabama politics. Delegates sought to make the state legislature more efficient, and reformers believed that home rule was the best solution. Under the Constitution of 1875, Alabama’s legislature passed 20 times more local legislation than general laws, so the legislative committee suggested a list of issues that the state legislature would not be able to address, such as establishing school districts, granting charters to corporations, and approving adoptions or divorces. As with all other issues, however, conservative interests prevailed, and as a result, the state legislature still spends most of its annual session passing local legislation. The convention also made the amendment process easier, leading to more than 800 amendments being added to the Constitution since 1901 and creating the longest constitution in the world. The most blatant voting and racist provisions were amended over the years to comply with federal law and civil rights acts, but because of inherent problems regarding home rule, public education funding, and tax policies, a constitutional reform movement has gained momentum in recent decades.

Further Reading

- Feldman, Glenn. The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

- Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

- McMillan, Malcolm Cook. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. Vol. 37, The James Sprunt Studies in History and Political Science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

- Riser, Robert Volney II. “Between Scylla and Charybdis: Alabama’s 1901 Constitutional Convention Assesses the Perils of Disfranchisement.” Masters thesis, University of Alabama, 2000.