Treaty of Fort Jackson

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson, or more properly the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814, was signed on August 9, 1814, and concluded the Creek War of 1813-1814 between the Red Stick faction of the Upper Creeks and the United States. The agreement was notable for forcing the Creeks to cede more than 21 million acres of land in the Mississippi Territory, much of it in present-day central and south Alabama, as well as in southern Georgia, to the United States. The land transfer opened up a vast fertile territory to white settlement and later led to the removal of the majority of the Creek Nation to the newly opened West.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson, or more properly the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814, was signed on August 9, 1814, and concluded the Creek War of 1813-1814 between the Red Stick faction of the Upper Creeks and the United States. The agreement was notable for forcing the Creeks to cede more than 21 million acres of land in the Mississippi Territory, much of it in present-day central and south Alabama, as well as in southern Georgia, to the United States. The land transfer opened up a vast fertile territory to white settlement and later led to the removal of the majority of the Creek Nation to the newly opened West.

The treaty was the result of Gen. Andrew Jackson’s decisive victory over the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which took place on March 27, 1814, in present-day Tallapoosa County. U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong tasked Maj. Gen. Thomas Pinckney and Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins with obtaining an agreement that included an undefined cession of land to pay for the war and free passage on roads through Creek territory and required the Creeks to hand over any leaders who had urged resistance to American expansion and promise to end all communications with Spanish outposts. Creek leaders deemed these provisions acceptable.

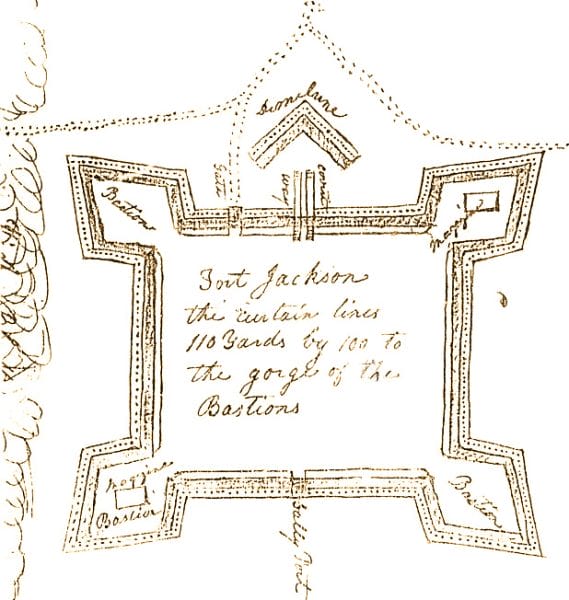

Diagram of Fort Jackson

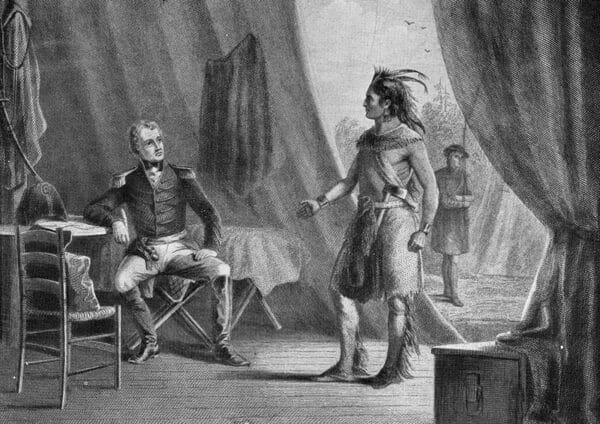

In mid-April, Jackson and his forces arrived at the site of the former Fort Toulouse and erected a stockade fort that was named in his honor (now Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson National Historic Park) near present-day Wetumpka. In early July, he ordered Hawkins to have the Creek chiefs meet with him on August 1. Sometime prior to the peace talks, Red Stick leader William Weatherford learned of Jackson’s order for his arrest and instead turned himself in to Jackson, who chastised the Creek leader for his role in the Fort Mims massacre. Weatherford, for his part, eloquently renounced further hostilities and sought food and clothing for the many Creeks displaced by the war and whose desperate condition was noted by officials at Fort Jackson.

Diagram of Fort Jackson

In mid-April, Jackson and his forces arrived at the site of the former Fort Toulouse and erected a stockade fort that was named in his honor (now Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson National Historic Park) near present-day Wetumpka. In early July, he ordered Hawkins to have the Creek chiefs meet with him on August 1. Sometime prior to the peace talks, Red Stick leader William Weatherford learned of Jackson’s order for his arrest and instead turned himself in to Jackson, who chastised the Creek leader for his role in the Fort Mims massacre. Weatherford, for his part, eloquently renounced further hostilities and sought food and clothing for the many Creeks displaced by the war and whose desperate condition was noted by officials at Fort Jackson.

Having recently been elevated to the rank of major general, Jackson was assigned as sole commissioner to represent the United States during treaty negotiations. Working under the broad conditions laid out by Armstrong, he proceeded to impose much harsher terms than any of the parties envisioned. Jackson thus earned the nickname “Sharp Knife” from the Creek negotiators, who included Lower Creek leader William McIntosh Jr. and Yuchi chief Timpoochee Barnard.

Fort Jackson Earthworks

To justify the terms of the treaty, Jackson cited an “unprovoked” war waged by the Creeks and violations of the 1790 Treaty of New York including the Fort Mims attack. He reasoned that the cession of land was the equivalent of expenses borne by the United States to prosecute the war. The treaty demanded that the Creek Nation stop communicating with the British and the Spanish and cease contact with agents and traders not licensed by the United States. In addition, it required that the Creeks allow the United States to construct military posts and trading houses and roads in Creek territory, return property taken from settlers, and surrender leaders who had instigated the war. For his part, Jackson promised that the United States would provide for the Creeks until they were able to build up sufficient stores of corn and assured them of access to federally sanctioned trading houses to procure clothing. Many of the Creeks who had allied with the United States objected that they were being punished for the offenses of the Red Sticks, most of whom were either dead or had taken refuge in Florida, still ready to make war. However, seeing little alternative but to sign or continue fighting, approximately 36 Creeks, including Tuckabatchee head man Big Warrior and one reported Red Stick leader, signed the treaty.

Fort Jackson Earthworks

To justify the terms of the treaty, Jackson cited an “unprovoked” war waged by the Creeks and violations of the 1790 Treaty of New York including the Fort Mims attack. He reasoned that the cession of land was the equivalent of expenses borne by the United States to prosecute the war. The treaty demanded that the Creek Nation stop communicating with the British and the Spanish and cease contact with agents and traders not licensed by the United States. In addition, it required that the Creeks allow the United States to construct military posts and trading houses and roads in Creek territory, return property taken from settlers, and surrender leaders who had instigated the war. For his part, Jackson promised that the United States would provide for the Creeks until they were able to build up sufficient stores of corn and assured them of access to federally sanctioned trading houses to procure clothing. Many of the Creeks who had allied with the United States objected that they were being punished for the offenses of the Red Sticks, most of whom were either dead or had taken refuge in Florida, still ready to make war. However, seeing little alternative but to sign or continue fighting, approximately 36 Creeks, including Tuckabatchee head man Big Warrior and one reported Red Stick leader, signed the treaty.

The land-cession requirement would have the most far-reaching and devastating effect on the Creeks in Alabama. As historians have noted, it was designed to pay for the war but also separate the Creeks remaining in present-day east-central Alabama from other Indian nations, from the Red Sticks in Florida, from the Spanish, and particularly from the British, with whom the United States was still at war. It also was intended to take away prime hunting grounds, thus pushing the Creeks toward farming and raising livestock and to secure the Old Federal Road leading to Mobile for military purposes. Although Jackson had considerable public support to impose the treaty, given the country’s intense desire to avenge Fort Mims, Hawkins believed it too harsh, taking nearly eight million acres from allied Indians. He was able to file for land claims on behalf of Lower Creeks who opposed the Red Sticks, resulting in 30 allotments.

The Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain and was signed December 24. Article IX, however, required the United States to restore to British-allied Indian nations any property, rights, or privileges that stood prior to 1811 and prior to hostilities. It essentially nullified the land cession in the treaty at Fort Jackson and returned lands won in other regions during the war. Jackson objected to the requirement on the grounds that it would make the nation less secure, and it was subsequently ignored by the United States. The Cherokees also protested that some of that land west of the Coosa River and south of the Tennessee belonged to them, but this issue was resolved by returning four million acres in a March 22, 1816, treaty. The former Creek land was opened to settlement and greatly expanded slave-based plantation agriculture. The vast majority of the Creeks remaining in east Alabama were removed west after the Second Creek War of 1836.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike, and Clay Williams. Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812. Charleston: History Press, 2008.

- Halbert, Henry S., and Timothy H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Edited by Frank L. Owsley Jr. 1895. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Pound, Merritt B. Benjamin Hawkins: Indian Agent. Athens, Ga.: the University of Georgia Press, 1951.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson & His Indian Wars. New York: Viking Press, 2001.

- ———. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767-1821. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1977.

- Waselkov, Gregory A. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-1814. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.