Forest Products Industry in Alabama

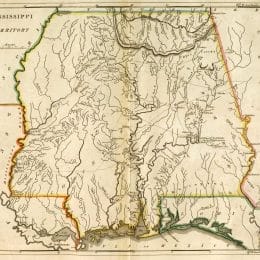

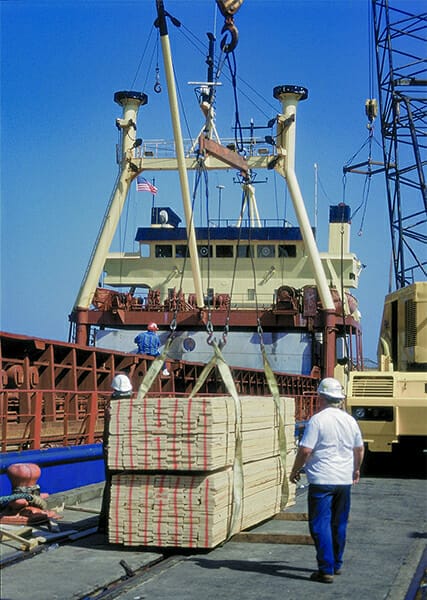

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Because Alabama is one of the most heavily forested states in the nation, the forestry products industry has played a large role in the state’s economy. Developing first as the timber industry and to a lesser extent naval stores (turpentine and other pine-resin products), the forest products industry came to include pulp and paper production in the twentieth century. In recent years, international competition has caused many companies to divest themselves of their lands and has pushed forest management practices and the forest products industry in new directions.

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Because Alabama is one of the most heavily forested states in the nation, the forestry products industry has played a large role in the state’s economy. Developing first as the timber industry and to a lesser extent naval stores (turpentine and other pine-resin products), the forest products industry came to include pulp and paper production in the twentieth century. In recent years, international competition has caused many companies to divest themselves of their lands and has pushed forest management practices and the forest products industry in new directions.

The region’s pre-historic Native American peoples used wood for constructing homes, towns, and ceremonial structures. They cleared land for farming and occasionally set fires in the woods to drive game out for hunting. By the time whites began settling in what is now Alabama, however, the Native American population had been dramatically reduced by disease, and the forests had largely recovered from their activities. It is estimated that in 1630, longleaf and other pines, as well as a variety of hardwoods, covered some 29,540,000 acres in Alabama.

Rise of the Timber Industry

White settlers came to Alabama primarily to farm; thus, they generally viewed forests as obstacles, with little interest in their economic potential. Settlers cleared land for farming, either by chopping down the trees or girdling them and then burning the fallen timber. In the remaining forests, they hunted and gathered nuts, berries, and herbs, and they built their furniture and structures out of wood.

One of the first water-powered sawmills in Alabama was built by Thomas Mendenhall on a tributary of the Conecuh River. The Conecuh was a convenient route for rafting rough-hewn pine timbers down to the Escambia River and into Pensacola Bay, where they were sold for export. Soon after Mendenhall established his mill, several other families who would become important in the Alabama lumber industry settled in the area. The community came to be known as Brewton and grew into one of Alabama’s lumbering centers. The south Alabama region was attractive to timber interests because of the prevalence of longleaf pine forests and accessibility to Gulf Coast manufacturing and marketing centers via the area’s rivers. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Mobile had a burgeoning lumber industry that was exporting nearly seven million feet of sawed lumber to various markets, including Cuba, Europe, South America, and even the California gold fields.

Turpentine Still in Calhoun County

The forests also provided raw materials for ship-building, as well as the tar, pitch, resin, and turpentine needed to maintain ships. The production of naval stores, as these byproducts were called, was extremely destructive to forests, and by the middle 1880s, the repeated tapping of pine trees for resin had destroyed hundreds of square miles of forests in south Alabama.

Turpentine Still in Calhoun County

The forests also provided raw materials for ship-building, as well as the tar, pitch, resin, and turpentine needed to maintain ships. The production of naval stores, as these byproducts were called, was extremely destructive to forests, and by the middle 1880s, the repeated tapping of pine trees for resin had destroyed hundreds of square miles of forests in south Alabama.

Large-scale logging and lumbering involving railroads and steam-powered logging equipment and mills did not become widespread in Alabama until the late nineteenth century. Thus, despite the absence of knowledge about silviculture and forest management, early loggers and lumbermen did not cause extensive damage to forests. Extensive clear-cutting and large-scale devastation came later. The early logging and milling operations were relatively small, employing the labor of farmers and other local people, including slaves in some cases.

On the eve of the Civil War, agriculture was the dominant sector of the Alabama economy. The state ranked second nationally in cotton production, and, with its neighbors Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana, produced half of the world’s crop. In the manufacturing sector, around 336 sawmills were operating in Alabama, the highest number of establishments in any industrial category. Combined with turpentine production, forest products, including such things as lumber, poles, shingles, and timbers, led in value of production, with a combined total of $2,621,241 in value of production, although the glory days of the industry were still in the future. By 1870, blacksmithing and milling establishments only narrowly outnumbered forest-related establishments.

Boom Times

By the late nineteenth century, Alabama, like the rest of the South, was in the midst of a timber industry boom. A huge influx of immigrants, the movement of people into the West, and the massive growth of the nation’s cities brought dramatic increases in demand for wood products. Railroads needed wood to make ties, cars, and buildings, and most new dwellings in the nation were made largely from wood. Farmers who moved to the generally treeless western prairies had to import wood to construct barns, fences, and other structures. During this period, the forests of the Northeast and Great Lakes states were rapidly shrinking as a result of overcutting by the lumber industries there.

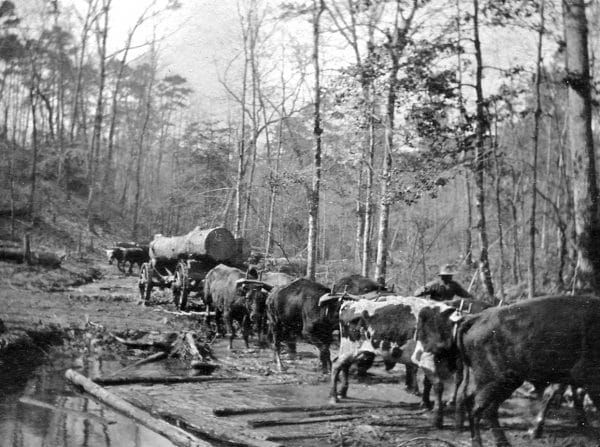

Ox Team

As the southern lumber boom began, labor in the industry was being transformed. Early loggers and lumbermen transported logs from the woods to the mills using animal-drawn carts and wagons and river rafts. In the late nineteenth century individual workers used or operated tools and machines that made them vastly more productive. Two-man, cross-cut saws replaced axes for felling trees, and steam-powered skidders and loaders proliferated. These inventions greatly increased the speed with which felled trees were dragged to rail lines and loaded onto flat cars for transport to the mills on narrow-gauge railroads. The new technology had significant environmental drawbacks. As skidders dragged felled timber to the tracks, they uprooted the new growth and seedlings in their paths. Mill owners replaced water wheels and turbines with enormous steam engines to power their machinery and introduced large band saws that could cut lumber more efficiently and faster than earlier circular saws.

Ox Team

As the southern lumber boom began, labor in the industry was being transformed. Early loggers and lumbermen transported logs from the woods to the mills using animal-drawn carts and wagons and river rafts. In the late nineteenth century individual workers used or operated tools and machines that made them vastly more productive. Two-man, cross-cut saws replaced axes for felling trees, and steam-powered skidders and loaders proliferated. These inventions greatly increased the speed with which felled trees were dragged to rail lines and loaded onto flat cars for transport to the mills on narrow-gauge railroads. The new technology had significant environmental drawbacks. As skidders dragged felled timber to the tracks, they uprooted the new growth and seedlings in their paths. Mill owners replaced water wheels and turbines with enormous steam engines to power their machinery and introduced large band saws that could cut lumber more efficiently and faster than earlier circular saws.

As in the early nineteenth century, many workers were small farmers or farm workers, both black and white, who also labored in the industry. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, more men worked full time in the forests and mills, and a few companies also employed convicts leased from county and state prisons. These types of labor were dangerous, and workers were injured by sharp saws and axes and limbs (called “widowmakers”) that fell from trees. Outside the forests, men were injured loading and unloading railroad cars and wagons and by overheated saws that occasionally exploded in the mills. Despite some efforts at organization in the early twentieth century, unions were not prevalent in the timber industry.

During the late nineteenth century, many large northern companies came South, clear-cut vast amounts of timber, and then moved on to other regions. In Alabama, however, some of the largest lumber companies were owned by local residents. Among these were the McGowin family of the W. T. Smith Lumber Company. This company was established in Butler County in the 1880s and then acquired and renamed by Autauga County and Birmingham lumberman W. T. Smith, who had started his own company in the 1850s. The firm was purchased by the McGowins in 1905, and they operated the company until 1966, when they sold their holdings to Union Camp.

T. R. Miller established the T. R. Miller Mill Company with a partner on Cedar Creek near Brewton. By 1891, Miller co-owned with David Blacksher and Alex McGowin 35,000 acres of timber, a large sawmill, a planing mill, five dry kilns, and 30 miles of log ditches. By 1913, the T. R. Miller firm employed more than 800 people and owned some 200,000 acres.

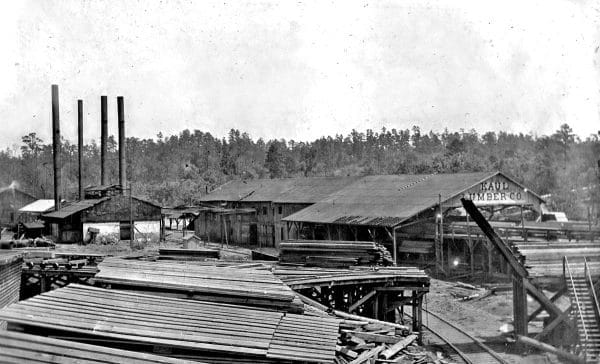

Kaul Lumber Company Sawmill

In addition to local owners, several outsiders established operations in the state, including the Kaul family of Pennsylvania, who began to acquire Alabama timberland and milling operations in 1889. By 1911, the company had more than 80,000 acres of timberland and constructed a manufacturing complex and company town at Kaulton near Tuscaloosa. The facility produced lumber until 1931. William D. Harrigan of Rhinelander, Wisconsin, joined fellow Wisconsinite Frederick Herrick in purchasing the Scotch Lumber Company at Fulton in 1902. By the early 1900s, the company controlled roughly 145,000 acres, and in 1928 the Harrigan family became sole owners of the firm.

Kaul Lumber Company Sawmill

In addition to local owners, several outsiders established operations in the state, including the Kaul family of Pennsylvania, who began to acquire Alabama timberland and milling operations in 1889. By 1911, the company had more than 80,000 acres of timberland and constructed a manufacturing complex and company town at Kaulton near Tuscaloosa. The facility produced lumber until 1931. William D. Harrigan of Rhinelander, Wisconsin, joined fellow Wisconsinite Frederick Herrick in purchasing the Scotch Lumber Company at Fulton in 1902. By the early 1900s, the company controlled roughly 145,000 acres, and in 1928 the Harrigan family became sole owners of the firm.

Sustainable Forestry Efforts

During the early twentieth century, as more and more forests were clearcut or otherwise depleted, national environmental leaders such as Gifford Pinchot began to warn of a looming “timber famine.” Public calls for conservation, including responsible forest management practices, began to appear. During the first decade of the century, the nation’s first three forestry schools

Scaling Trees

were established, bringing European management practices to America. Alabama had no institutions that offered instruction in sustainable forestry, and many of Alabama’s trained foresters came from Yale University, in Connecticut, or from neighboring state schools such as Louisiana State University and the University of Georgia. Because the forests of the South were being rapidly cut over, they offered the ideal setting to test forest management in the field. The Yale University School of Forestry initiated spring and summer field schools for their students hosted by the Kaul Lumber Company, the T. R. Miller Mill Company, and other Alabama firms, and important relationships developed as the companies hired Yale Forestry School graduates and employed faculty members as consultants.

Scaling Trees

were established, bringing European management practices to America. Alabama had no institutions that offered instruction in sustainable forestry, and many of Alabama’s trained foresters came from Yale University, in Connecticut, or from neighboring state schools such as Louisiana State University and the University of Georgia. Because the forests of the South were being rapidly cut over, they offered the ideal setting to test forest management in the field. The Yale University School of Forestry initiated spring and summer field schools for their students hosted by the Kaul Lumber Company, the T. R. Miller Mill Company, and other Alabama firms, and important relationships developed as the companies hired Yale Forestry School graduates and employed faculty members as consultants.

Among the important changes in forest management was the use of controlled burning, promoted by Austin Cary of the U.S. Forest Service and Yale faculty member Herman Haupt Chapman. Unlike other species, longleaf pines are adapted to periodic burning and depend on fire for their seeds to germinate. Julian McGowin of Alabama’s W. T. Smith Company joined forces with Arkansas lumberman Leslie K. Pomeroy to form the consulting firm of Pomeroy and McGowin (later Larson and McGowin), which became an important force in promoting responsible forest management.

From the late nineteenth century through World War I, the South was the nation’s leading lumber producer, peaking in 1901, when southern producers supplied one-third of the nation’s lumber. By 1910, Alabama had 1,819 lumber manufacturers that employed 22,409 workers and turned out products valued at $26,057,662. A decade later, Alabama had 1,774 sawmills that employed 22,097 workers and production valued at $61,317,0000. Alabama produced more than one billion board feet of softwoods and hardwoods, with yellow pine accounting for most of the output. The state ranked seventh nationally in lumber production, but, by the mid-1920s many companies had exhausted their lands and moved on. By 1931, Alabama was down to 320 lumbering establishments.

Forest Restoration

With forestry on the decline in the state, the federal government stepped in during the 1930s and began to acquire large tracts of largely cutover land for conservation purposes; these areas would become Alabama’s four national forests. Federal agencies such as the Soil Conservation Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the U.S. Forest Service joined state agencies such as the newly established Alabama Forestry Commission to promote responsible fire control and management and forest restoration. Forestry practices in the state were further enhanced with the establishment of the forestry program at the Alabama Polytechnic University (now Auburn University) in 1946. Tuskegee University established a forestry program two decades later, in 1968. The rise of professional forestry also contributed positively over the years to eradicate or control various problems in Alabama’s forests, including fusiform rust, pine beetle borers, and other difficulties.

Forest Restoration

With forestry on the decline in the state, the federal government stepped in during the 1930s and began to acquire large tracts of largely cutover land for conservation purposes; these areas would become Alabama’s four national forests. Federal agencies such as the Soil Conservation Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the U.S. Forest Service joined state agencies such as the newly established Alabama Forestry Commission to promote responsible fire control and management and forest restoration. Forestry practices in the state were further enhanced with the establishment of the forestry program at the Alabama Polytechnic University (now Auburn University) in 1946. Tuskegee University established a forestry program two decades later, in 1968. The rise of professional forestry also contributed positively over the years to eradicate or control various problems in Alabama’s forests, including fusiform rust, pine beetle borers, and other difficulties.

Rise of the Pulp and Paper Industry

Paper Mill in Wilcox County

As reforestation efforts gained traction, foresters and observers saw how quickly southern forests re-emerged on cutover lands where only a few seed trees had been left, thus demonstrating the short growth cycle for trees, especially pines, in the region. This realization, combined with technological developments, set the stage for the emergence of the pulp and paper industry. Formerly centered in the now-depleted white pine and hardwood areas of the Northeast, the paper industry shifted south. Southern pines had been considered too resinous to produce marketable paper. However, southern mills early on had demonstrated that pine pulp could produce kraft, a tough brown wrapping paper that was named for the pulping process by which it was made. Additionally, researchers such as Charles Holmes Herty of Savannah, Georgia, developed a process for producing a variety of other types of paper, including newsprint, from southern pines.

Paper Mill in Wilcox County

As reforestation efforts gained traction, foresters and observers saw how quickly southern forests re-emerged on cutover lands where only a few seed trees had been left, thus demonstrating the short growth cycle for trees, especially pines, in the region. This realization, combined with technological developments, set the stage for the emergence of the pulp and paper industry. Formerly centered in the now-depleted white pine and hardwood areas of the Northeast, the paper industry shifted south. Southern pines had been considered too resinous to produce marketable paper. However, southern mills early on had demonstrated that pine pulp could produce kraft, a tough brown wrapping paper that was named for the pulping process by which it was made. Additionally, researchers such as Charles Holmes Herty of Savannah, Georgia, developed a process for producing a variety of other types of paper, including newsprint, from southern pines.

Paper mills were an enormous monetary investment, they could not easily relocate if wood stocks became depleted, and they were extraordinarily expensive to restart if there was an interruption in production, so the cheap and productive timberland in the South was extremely appealing to manufacturers. Between 1925 and 1931, International Paper’s Southern Kraft division purchased three kraft mills and built three more, including a massive facility and headquarters at Mobile. The Illinois-based Westervelt family established the Gulf States Paper Company at Holt, Tuscaloosa County, in 1927. The industry was also attracted by Alabama’s cheap, abundant, and generally non-union labor force. By the early 1950s, seven wood-pulp mills were operating in the state.

Timber Industry Recovery

After the severe downturn that began in the late 1920s and continued during the Great Depression, the industry had begun to recover by the end of the 1930s. More than 600 sawmills, veneer mills, and cooperage-stock (barrel-making) mills operated in Alabama, employing more than 18,000 workers. By 1947, Alabama ranked first among southern states in lumber production, with $84,350,000 of value added by production.

Even as lumber companies made progress in sustainable forestry, they felt pressure from the increasing competition of the pulp and paper companies. Lumber producers and paper companies often competed intensely for ownership or management of the same land. Over time, these conflicts abated, with some companies becoming involved in both paper and lumber manufacture and foresters moving back and forth between the industries in their employment.

The industries did have common interests in such areas as fire control, freight rates, and land taxation. They sometimes cooperated through industry organizations to address these issues. The Southern Pine Association was created in 1914 to deal with a variety of forest issues, and it was followed in 1949 by the Alabama Forestry Association, which successfully lobbied the state legislature to tax timber land but not the trees that grew on it. Originally created by lumbermen and forest land owners, the AFA expanded in 1950 to bring in members from the pulp and paper industry. It remains a powerful force in Alabama politics.

Growing Controversy

The practices of corporate foresters were not immune to criticism. In the post-World War II period, many forestry schools received generous funding from forest products companies and began to turn out foresters whose emphasis was on growing as much timber as possible in the shortest period of time on the least possible acreage. Old-growth mixed-species forests were harvested, often by clear-cutting, and were frequently replaced with tree plantations that produced single-species crops, usually of loblolly pine, that were all harvested at once. Genetics research resulted in the development of fast-growing “super trees.” Wildlife scientists and others criticized these forests as aesthetically and biologically barren and argued that wildlife habitat, natural beauty, and recreation were largely ignored.

During the 1960s and 1970s, critics increasingly charged that the U.S. Forest Service managed the national forests essentially as “tree farms” to supply the timber needs of the forest products industry. As the environmental movement grew to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s, the verbal and political battles between industry spokesmen and environmentalists and wildlife scientists became louder and more bitter. Both forest products industry trade associations and environmental organizations intensified their political lobbying efforts. The forest management philosophies of the paper and lumber companies persisted, however, because they were extremely profitable.

Diversification and Decline

Both the lumber companies and paper manufacturers diversified and consolidated in the late twentieth century. Both adapted new technologies and enlarged their pool of products. Industrial technology research led to the invention of new packaging materials, pine plywood, oriented-strand board, and other products. International Paper Company began to acquire sawmills in the 1970s, as did Hammermill. Washington-based paper giant Weyerhaeuser purchased land in Alabama in 1954 and by the 1980s had constructed a lumber manufacturing plant at Lamar. The T. R. Miller Mill Company aligned with Container Corporation of America in 1955 to construct a paper mill. By 1968, Alabama was the second leading pulp producer in the nation.

By the 1990s, Alabama had more acres of trees than at the time of early European exploration and settlement, although these “forests” were now comprised almost exclusively of one or two species of pine. This overabundance of pines led to a wood surplus that depressed prices. In addition, the forest products industries had become increasingly international, and wood from other countries began flooding the U.S. market. Forest products companies began harvesting trees from other countries that were not subject to American taxes and environmental protections, a trend that continues with the expansion of the global economy.

As a result, forest land in Alabama and other southern states lost much of its value, and companies became attractive targets for corporate mergers and takeovers. Assured of an adequate wood supply from non-industrial private lands and foreign producers, companies moved quickly to divest their landholdings. In Alabama, Georgia-Pacific Corporation, International Paper Company, and MeadWestvaco, among others, sold off most of their lands. The degree of change of ownership and of ownership type is virtually unprecedented in the history of U.S. timberland. Among the large transfers during the early twenty-first century were sales of 4.7 million acres by Georgia-Pacific Corporation to Plum Creek Timber Company, and sales of 9.7 million acres by International Paper Company and 4.6 million acres by Boise-Cascade. The value of total corporate forestland sales was estimated to be approximately $30 billion, and the total acreage more than 27 million acres. In 1996, about 95 percent of industrial forestland in the United States was owned by vertically integrated forest product firms, but by 2006 at least half of the total acreage was estimated to be owned by Timber Investment Management Organizations (TIMOs) or Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), with timberlands valued at $15.7 billion. In the meantime, the last giant vertically integrated company, Weyerhaeuser, began restructuring as an REIT. These entities purchase land for a variety of uses, including commercial, residential, and recreational development; immediate harvesting in preparation for resale; long-term management for timber; and preservation, among others.

The rise of the environmental movement also affected Alabama’s forests in various ways. The U.S. Forest Service moved from a wood production emphasis in the national forests toward less harvesting and a greater emphasis on recreation, wildlife restoration and management, and preservation of biologically significant areas such as the Sipsey Wilderness in the Bankhead National Forest. The private sector also paid increasing attention to wildlife management, protection of endangered species, streamside protection by loggers, and other values promoted by environmental activists and scientists. Industry responded to environmental criticisms in various ways, including the adoption by the late twentieth century of the Sustainable Forestry Initiative and other certification programs. Alabama’s forests entered a new age, with a wider spectrum of owners, citizens, and users demanding a voice in their preservation, uses, management, and future.

At the same time, as pressure from environmentalists resulted in reduced timber production from public lands in the West, timber harvests from private lands in the South, including Alabama, increased. By this time, sawmills were larger and more efficient. In the early twenty-first century, the Alabama forest-products industry recorded $11.2 billion in sales, with forest-products manufacturing accounting for the vast majority of that total. The industry employed approximately 23,000 workers and contributed some $7.9 billion in value-added impact on the state economy.

Further Reading

- Burdette, Don. “The Southern Forests: A Legacy of Nations.” Alabama’s Treasured Forests 14 (Fall 1995): 27, 30-31.

- ———. “The Southern Forests: 1800-1850.” Alabama’s Treasured Forests 15 (Winter 1996): 23.

- ———. “The Southern Forests: 1850-1930.” Alabama’s Treasured Forests 15 (Spring 1996): 26-27.

- ———. “The Southern Forests: An Environmental and Economic Success Story.” Alabama’s Treasured Forests 15 (Summer 1996): 14.

- Fickle, James E. Green Gold: Alabama’s Forests and Forest Industries. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2014.

- Lawson, Thomas Jr. Logging Railroads of Alabama. Birmingham, Ala: Cabbage Stack Publishing, 1996.

- Randolph, John N. The Battle for Alabama’s Wilderness: Saving the Great Gymnasiums of Nature. Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 2005.