Federal Road in Alabama

Old Federal Road

Originally designated as a postal route through the Indian frontier, the Federal Road, which stretched through Creek territory in lower Alabama, became a dynamic feature of the geography of the American historical landscape. A second Federal Road, initially called the Georgia Road, passed through Cherokee lands, connecting Savannah, Georgia, with Knoxville, Tennessee. Like previous avenues west, such as the Wilderness Road, Alabama’s Federal Road helped usher in a new era of national expansion, communication, and exploitation of Native American groups. It functioned as a major thoroughfare for the western migration of settlers and slaves into the Old Southwest for the first three decades of the nineteenth century. As a military road, it aided in the movement of troops sent to defend the vulnerable western margins of the United States.

Old Federal Road

Originally designated as a postal route through the Indian frontier, the Federal Road, which stretched through Creek territory in lower Alabama, became a dynamic feature of the geography of the American historical landscape. A second Federal Road, initially called the Georgia Road, passed through Cherokee lands, connecting Savannah, Georgia, with Knoxville, Tennessee. Like previous avenues west, such as the Wilderness Road, Alabama’s Federal Road helped usher in a new era of national expansion, communication, and exploitation of Native American groups. It functioned as a major thoroughfare for the western migration of settlers and slaves into the Old Southwest for the first three decades of the nineteenth century. As a military road, it aided in the movement of troops sent to defend the vulnerable western margins of the United States.

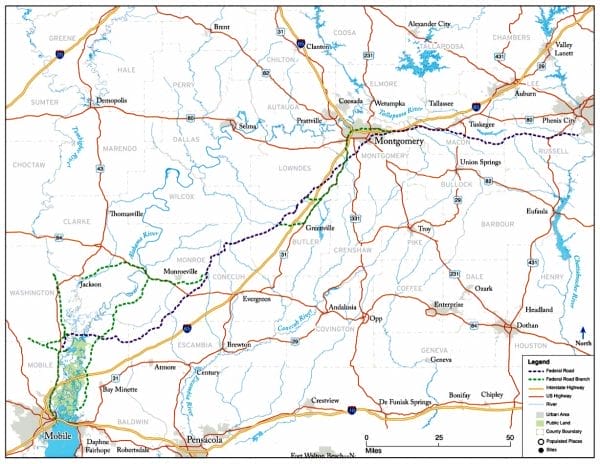

Map of the Federal Road

In 1803, Pres. Thomas Jefferson authorized the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, effectively doubling the size of the United States. Jefferson understood the importance of safe and adequate transportation for military defense and commercial interests in the newly acquired settlements of Louisiana. He lobbied to build the road through Creek territory, recognizing that the future of southern commerce depended on easy access to the port of New Orleans. Congress passed enabling legislation giving the president power to establish lines of communication to the new territory. Comprehending the importance of such a project, Postmaster General Gideon Granger petitioned Congress in November 1803 for funds to construct a postal road connecting New Orleans with the eastern cities of Charleston, South Carolina; Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Up until this time, travelers used a series of Indian routes to transport messages through the backcountry of what was then the Mississippi Territory, which included the present-day state of Alabama. The southern frontier of the early national period was a medley of cultures and loyalties, often dangerous and always difficult to traverse. In addition to their concerns about having no formal postal service to the territory, federal officials understood that a large portion of the proposed road would cross through territory within the Creek Nation. Road construction would therefore require the acquisition of that land by whatever means necessary.

Map of the Federal Road

In 1803, Pres. Thomas Jefferson authorized the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, effectively doubling the size of the United States. Jefferson understood the importance of safe and adequate transportation for military defense and commercial interests in the newly acquired settlements of Louisiana. He lobbied to build the road through Creek territory, recognizing that the future of southern commerce depended on easy access to the port of New Orleans. Congress passed enabling legislation giving the president power to establish lines of communication to the new territory. Comprehending the importance of such a project, Postmaster General Gideon Granger petitioned Congress in November 1803 for funds to construct a postal road connecting New Orleans with the eastern cities of Charleston, South Carolina; Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Up until this time, travelers used a series of Indian routes to transport messages through the backcountry of what was then the Mississippi Territory, which included the present-day state of Alabama. The southern frontier of the early national period was a medley of cultures and loyalties, often dangerous and always difficult to traverse. In addition to their concerns about having no formal postal service to the territory, federal officials understood that a large portion of the proposed road would cross through territory within the Creek Nation. Road construction would therefore require the acquisition of that land by whatever means necessary.

William McIntosh

A new generation of Creek political figures had emerged at the turn of the nineteenth century. Multiracial tribal leaders such as Alexander McGillivray and William McIntosh sought to challenge the authority of the traditional Creek leadership by creating alliances with their connections among the colonial forces and European traders and businessmen. These and other Creek men seeking political power signed unsanctioned and illegitimate treaties with federal officials for large sections of territory in Georgia. By 1805, a series of treaties had transferred millions of acres of Creek Confederacy land in Georgia to the federal government, and officials began making plans for a road through that territory. Proponents of the controversial road promised economic benefits to the Creek Nation from travelers moving through their country. Indeed, the 1805 Treaty of Washington stipulated that Creeks were permitted to maintain inns, taverns, stagecoach stops, and way stations for postal riders along the route. These promises would prove to be empty, and tensions caused by the increased traffic through Creek country would eventually lead to war and removal for the Creeks.

William McIntosh

A new generation of Creek political figures had emerged at the turn of the nineteenth century. Multiracial tribal leaders such as Alexander McGillivray and William McIntosh sought to challenge the authority of the traditional Creek leadership by creating alliances with their connections among the colonial forces and European traders and businessmen. These and other Creek men seeking political power signed unsanctioned and illegitimate treaties with federal officials for large sections of territory in Georgia. By 1805, a series of treaties had transferred millions of acres of Creek Confederacy land in Georgia to the federal government, and officials began making plans for a road through that territory. Proponents of the controversial road promised economic benefits to the Creek Nation from travelers moving through their country. Indeed, the 1805 Treaty of Washington stipulated that Creeks were permitted to maintain inns, taverns, stagecoach stops, and way stations for postal riders along the route. These promises would prove to be empty, and tensions caused by the increased traffic through Creek country would eventually lead to war and removal for the Creeks.

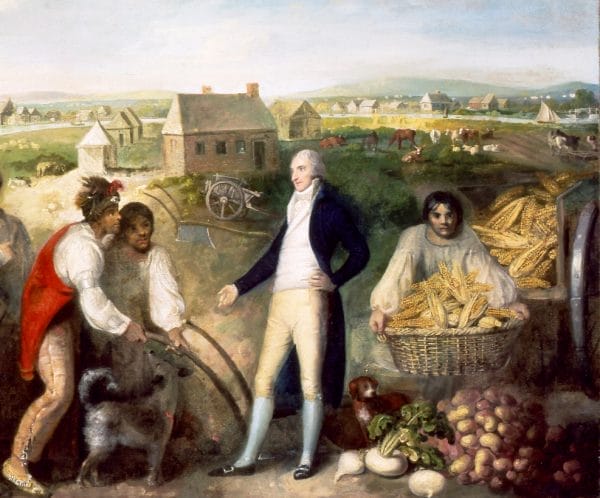

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

In April 1806, Congress appropriated $6,400 to build a postal road through the Creek Nation that would link Athens, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert on the Mobile River north of Mobile. Granger employed Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins to recruit Indian guides for the road’s builders and to assure tribal leaders cooperated with the effort. Creek leaders eventually conceded to the road’s construction in large part because of the influence of William McIntosh, who promised personal gains to those who consented. When completed, the post road would connect Washington and New Orleans over a distance of some 1,100 miles—300 miles shorter than the existing Natchez Trace. The construction effort was plagued by setbacks from the very beginning, however. At a mere four feet wide, the route crossed numerous water courses in Georgia and the Mississippi Territory. Recruited laborers were forced to contend with working in areas prone to seasonal flooding as well as numerous managerial setbacks and near constant illness. On August 15, 1806, a federal contract was signed and the postal route began in earnest from Athens, Georgia, to New Orleans. As more travelers made the arduous trek on the Federal Road and word was relayed back east about the hazards of the new route, many people chose to take the longer but more passable Natchez Trace through what is now north Alabama.

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

In April 1806, Congress appropriated $6,400 to build a postal road through the Creek Nation that would link Athens, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert on the Mobile River north of Mobile. Granger employed Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins to recruit Indian guides for the road’s builders and to assure tribal leaders cooperated with the effort. Creek leaders eventually conceded to the road’s construction in large part because of the influence of William McIntosh, who promised personal gains to those who consented. When completed, the post road would connect Washington and New Orleans over a distance of some 1,100 miles—300 miles shorter than the existing Natchez Trace. The construction effort was plagued by setbacks from the very beginning, however. At a mere four feet wide, the route crossed numerous water courses in Georgia and the Mississippi Territory. Recruited laborers were forced to contend with working in areas prone to seasonal flooding as well as numerous managerial setbacks and near constant illness. On August 15, 1806, a federal contract was signed and the postal route began in earnest from Athens, Georgia, to New Orleans. As more travelers made the arduous trek on the Federal Road and word was relayed back east about the hazards of the new route, many people chose to take the longer but more passable Natchez Trace through what is now north Alabama.

Fort Mitchell

In 1811, as tensions between the United States and Great Britain escalated, the federal government authorized the widening of the narrow path into a 16-foot-wide military road capable of carrying wagons and soldiers westward to counter the threat of a possible British attack along the Gulf Coast. Built by soldiers for soldiers, the road opened in November 1811 and intersected with the previous postal route from Athens down to the Chattahoochee River near modern-day Columbus, Georgia. The entire course ran from Milledgeville, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert on the Mobile River and on to New Orleans. Unlike the postal path of five years earlier, however, the architects of the new military road were not nearly as sensitive to the considerations of the Creek chieftains. Increased traffic worsened existing tensions between whites and Creeks. Benjamin Hawkins reported that 3,726 people heading westward passed by his agency on the Flint River between October 1811 and March 1812.

Fort Mitchell

In 1811, as tensions between the United States and Great Britain escalated, the federal government authorized the widening of the narrow path into a 16-foot-wide military road capable of carrying wagons and soldiers westward to counter the threat of a possible British attack along the Gulf Coast. Built by soldiers for soldiers, the road opened in November 1811 and intersected with the previous postal route from Athens down to the Chattahoochee River near modern-day Columbus, Georgia. The entire course ran from Milledgeville, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert on the Mobile River and on to New Orleans. Unlike the postal path of five years earlier, however, the architects of the new military road were not nearly as sensitive to the considerations of the Creek chieftains. Increased traffic worsened existing tensions between whites and Creeks. Benjamin Hawkins reported that 3,726 people heading westward passed by his agency on the Flint River between October 1811 and March 1812.

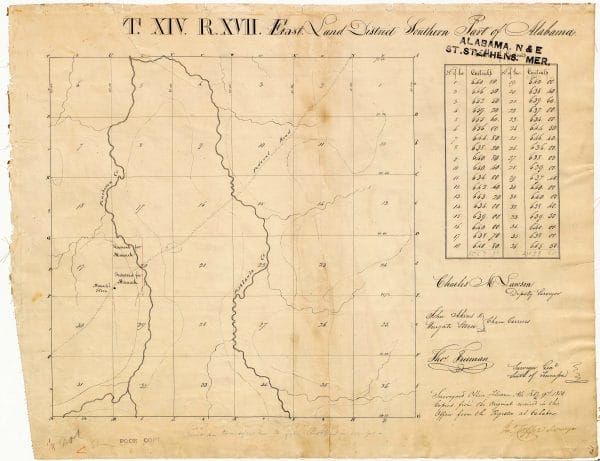

Map of Manack Store

Roads and increased non-Indian travel through Creek territory inflamed factionalism in the Creek towns and helped inaugurate a violent sequence of events that led to the Creek War of 1813-14 and the removal of the Creeks from their homeland. The Federal Road’s logistical significance was also marked by the construction of several forts, including Fort Mitchell. Other frontier outposts followed in the wake of the advancing American army as it fought the Red Stick faction of Creek Indians. After the war, the Federal Road became an artery for settlers who migrated into the Mississippi Territory in droves, no longer hindered by the presence of the powerful Creek Confederacy. Families moving from older Tidewater states like Virginia and the Carolinas carried their belongings in crudely constructed wagons made from large wooden barrels called hogsheads. Between 1790 and 1850, these primarily white yeomen farmers would bring large-scale plantation agriculture and the approximately one million enslaved African workers that made it possible, to the frontier, transforming the wilderness into a region defined by its cotton-based economy.

Map of Manack Store

Roads and increased non-Indian travel through Creek territory inflamed factionalism in the Creek towns and helped inaugurate a violent sequence of events that led to the Creek War of 1813-14 and the removal of the Creeks from their homeland. The Federal Road’s logistical significance was also marked by the construction of several forts, including Fort Mitchell. Other frontier outposts followed in the wake of the advancing American army as it fought the Red Stick faction of Creek Indians. After the war, the Federal Road became an artery for settlers who migrated into the Mississippi Territory in droves, no longer hindered by the presence of the powerful Creek Confederacy. Families moving from older Tidewater states like Virginia and the Carolinas carried their belongings in crudely constructed wagons made from large wooden barrels called hogsheads. Between 1790 and 1850, these primarily white yeomen farmers would bring large-scale plantation agriculture and the approximately one million enslaved African workers that made it possible, to the frontier, transforming the wilderness into a region defined by its cotton-based economy.

Watkins House

With the advent of steamboats and railroads, travel over the Federal Road diminished considerably. Worsening economic times in 1837 further reduced traffic along the road, blunting the land rush known as “Alabama Fever” that characterized the earlier settlement drive. In 1844, Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph radically improved communication across large distances, lessening the need for frontier post roads as well. Although much of the Federal Road has disappeared, portions of it remain. In Alabama, they can be found in Macon, Monroe, and Conecuh Counties, among others.

Watkins House

With the advent of steamboats and railroads, travel over the Federal Road diminished considerably. Worsening economic times in 1837 further reduced traffic along the road, blunting the land rush known as “Alabama Fever” that characterized the earlier settlement drive. In 1844, Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph radically improved communication across large distances, lessening the need for frontier post roads as well. Although much of the Federal Road has disappeared, portions of it remain. In Alabama, they can be found in Macon, Monroe, and Conecuh Counties, among others.

Much of what is currently known about the history of the Old Federal Road in Alabama is based on research by Henry deLeon Southerland and J. Elijah Brown, who wrote the first book-length study of the road. A number of projects related to the road are currently underway, including excavations at a site known as Manack’s Store in Pintlala and projects that will survey the route of the road and create an interactive Web site allowing users to “travel” the road.

Further Reading

- Braund, Kathryn E, Gregory A Waselkov, and Raven M. Christopher. The Old Federal Road in Alabama: An Illustrated Guide. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019.

- Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- Hudson, Angela Pulley. Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Pickett, Albert James. History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. 1851. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1971.

- Christopher, Raven, Gregory Waselkov, and Tara Potts. Archaeological Testing along the Federal Road: Exploring the Site of “Manack’ Store,” Montgomery County, Alabama. Hope Hull, Ala.: Pintlala Historical Association, 2011.

- Southerland, Henry deLeon, and Elijah Brown. The Federal Road through Georgia, the Creek Nation and Alabama, 1806-1836. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989.