J. Thomas Heflin

J. Thomas Heflin

Alabama probably has not had a more colorful or controversial U.S. senator than J. Thomas Heflin, or as he was more commonly called, “Cotton Tom” Heflin. He is known as the “Father of Mother’s Day,” having written and achieved passage of the national holiday. But he is also notable as one of the era’s most vehement supporters of convict leasing and white supremacy, having helped draft the language in the 1901 Constitution that essentially barred African American Alabamians from voting. His uncle, Robert Stell Heflin, was a Union sympathizer during the Civil War and was the first member of the family to serve in the U.S. Congress. His nephew, Howell Heflin, would later serve in a number of important capacities in Alabama, including Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court and U.S. senator from Alabama.

J. Thomas Heflin

Alabama probably has not had a more colorful or controversial U.S. senator than J. Thomas Heflin, or as he was more commonly called, “Cotton Tom” Heflin. He is known as the “Father of Mother’s Day,” having written and achieved passage of the national holiday. But he is also notable as one of the era’s most vehement supporters of convict leasing and white supremacy, having helped draft the language in the 1901 Constitution that essentially barred African American Alabamians from voting. His uncle, Robert Stell Heflin, was a Union sympathizer during the Civil War and was the first member of the family to serve in the U.S. Congress. His nephew, Howell Heflin, would later serve in a number of important capacities in Alabama, including Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court and U.S. senator from Alabama.

James Thomas Heflin was born on April 9, 1869, at Louina, Randolph County, to physician Wilson Lumpkin Heflin and Lavicie Catherine Phillips Heflin. His grandfather, Wyatt Heflin, was one of the first settlers of the county and served in the Alabama State Legislature. Heflin attended local public schools and then entered Southern University (now Birmingham-Southern University), transferring to the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Auburn University). Heflin left college before graduating to study law under an attorney in LaFayette, Chambers County, and completed his law degree in 1893. Heflin worked as a courthouse clerk and was elected mayor of LaFayette two months after passing the state bar.

An excellent orator and storyteller, Heflin became a popular figure and served two highly regarded terms as LaFayette’s mayor. On December 18, 1895, he married Minnie Kate Schuessler, of LaFayette; the couple had four children, three of whom died as toddlers. In 1896, he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives and re-elected two years later. In 1901, Heflin was elected as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, the aim of which was to create a document that would concentrate power in the hands of the state government and wealthy landowners and businessmen.

Senator Heflin and Cotton Growers at U.S. Capitol

In 1902, Heflin successfully ran for secretary of state but served only half of his four-year term; upon the death of U.S. Representative Charles W. Thompson, Heflin was elected to take his place in the U.S. Congress, representing Alabama’s Fifth Congressional District. During his term, Heflin fought to expand rural mail routes, regulate railroads, and set more favorable cotton prices, an effort that earned him the title “Cotton Tom.” In 1913, Heflin was chosen as the first southerner since the Civil War to deliver the principal address for the annual Memorial Day Observance in the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Senator Heflin and Cotton Growers at U.S. Capitol

In 1902, Heflin successfully ran for secretary of state but served only half of his four-year term; upon the death of U.S. Representative Charles W. Thompson, Heflin was elected to take his place in the U.S. Congress, representing Alabama’s Fifth Congressional District. During his term, Heflin fought to expand rural mail routes, regulate railroads, and set more favorable cotton prices, an effort that earned him the title “Cotton Tom.” In 1913, Heflin was chosen as the first southerner since the Civil War to deliver the principal address for the annual Memorial Day Observance in the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Heflin’s political philosophies would by today’s standards place him somewhere to the left of the political center on some issues, such as labor rights and industrial development, and to the far right on others, most particularly his views on race, women’s suffrage, and states’ rights. These views were shared by many politicians at the time, however, and were not detrimental to his career in politics. His tendency to be outspoken against and, in many instances, blatantly insulting to those who opposed him ultimately doomed his chances on the national stage. For example, at the height of the women’s suffrage movement in 1913, a national march was scheduled in Washington. In the spirited debate on the issue that took place in the House, Heflin, who strongly opposed a woman’s right to vote, sparked laughter when he mocked his Alabama colleague Richmond Pearson Hobson, a supporter of the movement, by suggesting that he wear a bonnet and a dress.

More damning was an incident related to a bill introduced by Heflin requiring segregated seating on Washington streetcars. As the bill was being considered, Heflin forcibly ejected from a streetcar an African American man who was seated among white riders. When the man attempted to defend himself, Heflin produced a revolver and shot wildly, striking a tourist from New York City in the hip. Heflin was indicted, but the charges were dropped when he paid the man’s hospital expenses and declared he had acted in self-defense by claiming he was protecting a woman who was being insulted by the man whom he ejected.

After serving eight consecutive terms in the House, Heflin got a chance to represent Alabama in the U.S. Senate in 1920 with the passing of John Bankhead Sr. In the spirited campaign to fill Bankhead’s unexpired term, Heflin defeated Emmet O’Neal, a former Alabama governor, and Frank S. White, who had served in the Senate in 1914. His seat in the House was taken by Calhoun County native William Bismarck Bowling. Reelected in 1924, Heflin devoted most of his efforts to supporting Prohibition and promoting anti-Catholicism. His political career probably peaked in 1926, when he led a coalition of activists from the resurging Ku Klux Klan and Anti-Saloon League to sweep most of the state’s Democratic primaries. His growing support among the so-called “poor whites” of north Alabama alarmed Black Belt leaders, who grew concerned that their control over the Democratic party machinery and state legislature was ebbing. They also feared that he might lead a movement to establish a third political party. Party leaders and their special interests thus began to formulate plans behind the scenes to bring him down.

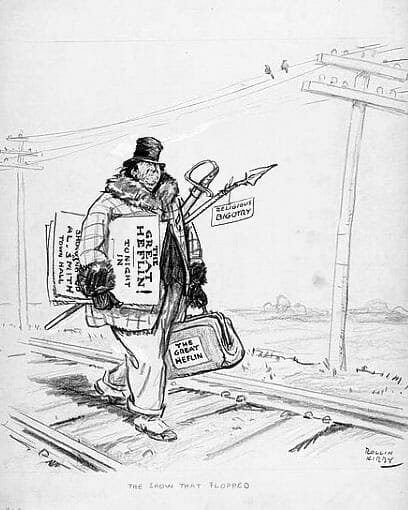

J. Thomas Heflin Political Cartoon

Heflin’s actions during the 1928 presidential campaign gave his adversaries the ammunition they needed. In that contest, Democratic candidate Al Smith, then governor of New York, faced serious opposition for his support for repealing Prohibition and was the object of bigotry for his Catholicism. Whether sincere or sensing a political coup that could help him in his desire to form a third party in Alabama, Heflin bolted the Democratic party and supported the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover. In speeches throughout the state, he accused Smith and the Catholic Church of conspiring to overthrow the U.S. government. Huge crowds cheered him in Birmingham’s Municipal Auditorium and Montgomery’s Cramton Bowl, where he unleashed bitter attacks on Smith, African Americans, and efforts to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, which established Prohibition.

J. Thomas Heflin Political Cartoon

Heflin’s actions during the 1928 presidential campaign gave his adversaries the ammunition they needed. In that contest, Democratic candidate Al Smith, then governor of New York, faced serious opposition for his support for repealing Prohibition and was the object of bigotry for his Catholicism. Whether sincere or sensing a political coup that could help him in his desire to form a third party in Alabama, Heflin bolted the Democratic party and supported the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover. In speeches throughout the state, he accused Smith and the Catholic Church of conspiring to overthrow the U.S. government. Huge crowds cheered him in Birmingham’s Municipal Auditorium and Montgomery’s Cramton Bowl, where he unleashed bitter attacks on Smith, African Americans, and efforts to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, which established Prohibition.

Heflin in turn was attacked in editorials in the Birmingham News and the Montgomery Advertiser. They called Heflin’s actions detrimental to business interests and industrial development in the state and depicted him as a tool of the Ku Klux Klan and the Republican Party. In the election, however, Smith carried the state by only 7,000 votes, as compared with the state Democratic margin of victory in 1924 of 68,000 votes. Ironically, Heflin attributed Smith’s defeat nationally to a strong turnout of women among the voters.

Having earned the wrath of the state Democratic hierarchy, Heflin was barred from the 1930 senatorial campaign. Never one to back down, Heflin responded by organizing the Jeffersonian Democrat Party and went on the attack. He had little success in raising support, however. State business leaders rejected him for his racist and anti-Catholic views, which they viewed as detrimental to fostering a welcoming climate for new industry. And the onset of the Great Depression served only to increase these concerns. That same year, Heflin formally submitted a letter of protest to the Congressional Record chastising the state of New York for allowing an interracial marriage. When the votes for the 1930 senatorial elections were tallied, Heflin suffered a crushing defeat to John H. Bankhead II, who surpassed him by a margin of 50,000 votes. Heflin challenged the results, lodging charges of fraud and tallying up legal costs of more than $100,000, but his formal protest to the U.S. Senate was dismissed in April 1932. Five years later, he made a strong bid for Hugo Black’s vacant Senate seat against Congressman Lister Hill, charging him with being soft on the perceived threat of Communism and criticizing him for favoring progressive reforms to wage and workhour regulations. Hill easily defeated him in the 1937 senatorial contest, however.

In addition to his elected positions, Heflin also served in two appointed positions. In 1935, he was named as a special representative to the Federal Housing Administration, serving for a year; he served in that capacity again from 1939 to 1942. In between those appointments, he served as a special assistant to the U.S. Attorney General from 1936 to 1937. In his later years, Heflin made periodic public speeches on various issues of the day. In the 1948 presidential election, Heflin aligned with more traditional Democratic interests when he refused to support States’ Rights Democrat (Dixiecrat) candidate Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. Heflin died on April 22, 1951, and was buried at Lafayette Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama United States Senators by Elbert L. Watson (Huntsville, Ala: Strode Publishers, 1982).