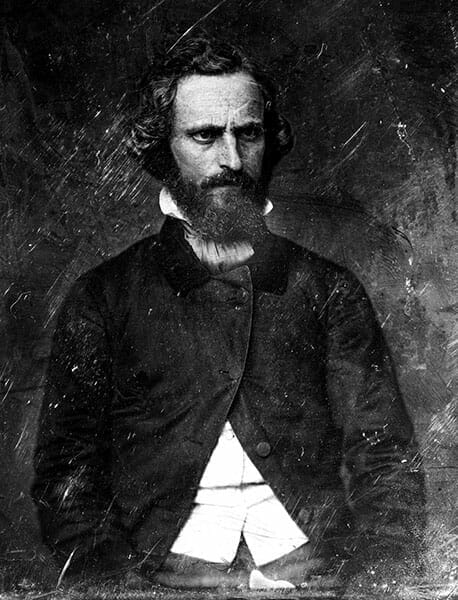

Clement Claiborne Clay

Clement Claiborne Clay (1816-1882) was a legislator and lawyer who was a strong advocate of secession. During the Civil War, he served in the Confederate Congress and then in Canada as an agent of the Confederate government working to undermine the Union. At war’s end, he was imprisoned as a suspect in the plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln but was freed without being formally charged. In poor health, he returned to Alabama and remained largely on his plantation until his death.

Clement Claiborne Clay

Clay was born December 16, 1816, the eldest son of Alabama legislator and governor Clement Comer Clay and Susanna Claiborne Withers Clay, in Huntsville, Madison County. He was related to Kentucky politician Henry Clay on his father’s side. Clay attended Greene Academy and the University of Alabama, graduating in 1834. He then earned a law degree from the University of Virginia in 1839. He was admitted to the bar on October 2 of that year and established a law firm with his father and Alabama legislator and author Jeremiah Clemens, who left the firm in 1841. In August 1842, Clay was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives with the strong backing of his father. On February 1, 1843, he married the politically connected Virginia Tunstall of Tuscaloosa. A North Carolinian, Tunstall had moved to Tuscaloosa in 1831 after her mother’s death to live with relatives, who included wealthy planter Alfred Battle and state politician Thomas Tunstall. She also served as hostess for her uncle, Judge Henry W. Collier, who later became governor of Alabama and whose home was the headquarters of Democratic party leaders.

Clement Claiborne Clay

Clay was born December 16, 1816, the eldest son of Alabama legislator and governor Clement Comer Clay and Susanna Claiborne Withers Clay, in Huntsville, Madison County. He was related to Kentucky politician Henry Clay on his father’s side. Clay attended Greene Academy and the University of Alabama, graduating in 1834. He then earned a law degree from the University of Virginia in 1839. He was admitted to the bar on October 2 of that year and established a law firm with his father and Alabama legislator and author Jeremiah Clemens, who left the firm in 1841. In August 1842, Clay was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives with the strong backing of his father. On February 1, 1843, he married the politically connected Virginia Tunstall of Tuscaloosa. A North Carolinian, Tunstall had moved to Tuscaloosa in 1831 after her mother’s death to live with relatives, who included wealthy planter Alfred Battle and state politician Thomas Tunstall. She also served as hostess for her uncle, Judge Henry W. Collier, who later became governor of Alabama and whose home was the headquarters of Democratic party leaders.

Clay was re-elected to the Alabama House two more times. In 1848, he was elected a county judge in Madison County. In the early years of his legislative service, Clay was a loyal Jacksonian Democrat but as the power of the Whig Party increased nationally and sectional strife increased, he became a leader in reorganizing the Democratic party in Alabama. Clay followed state’s rights radical William Lowndes Yancey‘s lead and became an increasingly vocal and visible supporter of states’ rights and also decided to seek a higher political office. In 1853, he was defeated in his run for a seat in Congress by Williamson Cobb, the plain-speaking representative from Madison County who was popular with many uneducated and pro-Union white farmers. Clay was then nominated by his party to run for the U.S. Senate and soundly defeated incumbent and former law partner Jeremiah Clemens for his seat.

Clay faithfully supported Pres. Franklin Pierce but ultimately found that this loyalty paid few political dividends. For example, he worked unsuccessfully to obtain land grants to aid the construction of three Alabama railroads. Clay was re-elected in 1857, two years before his term was set to expire, in an early election made necessary by the biannual meeting system of the Alabama State Legislature. Clay easily defeated his opponent, outgoing governor John A. Winston, who opposed support for industrial and business interests.

In Washington, as forces on either side of the slavery question coalesced into factions, the articulate Clay quickly became known as a leading defender of states’ rights, even voicing the extreme position of favoring reopening the African slave trade, a policy firmly opposed by fellow Alabama senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick. Clay opposed almost every compromise measure, claiming that most of the legislation required the South to surrender to federal power. Firmly entrenched with Yancey’s dominant faction of the Alabama Democratic party, Clay found himself at odds with his own more moderate, pro-Unionist constituents in north Alabama.

In January 1861, after Republican Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 triggered the secession of several southern states, including Alabama, Clay joined most of his southern colleagues in withdrawing from the U.S. Congress. For a short while, Clay, who had been suffering from ill health for some time, confined himself to his Huntsville cottage at the health resort in Monte Sano, east of Huntsville, to regain his strength. By October, however, he had announced his candidacy for a seat in the Senate of the newly formed Confederate State of America (CSA). Clay won a hard-fought battle with Butler County native Thomas Watts, who later would become governor in 1863. The election required 10 ballots to reach a decision, and Clay failed to carry his own Union-sympathizing Madison County. His term in the Confederate Congress was largely undistinguished, most of his effort being given to criticism of CSA president Jefferson Davis and his governing methods. Many people believed that Clay’s criticism resulted from his loyalty to Yancey, who had been bypassed for an appointment to any high political office in the Confederate government.

In November 1863, Clay was defeated for reelection by Richard Wilde Walker, the youngest son of politician and early settler of Huntsville John Williams Walker; the defeat was particularly bitter as the Walker and Clay families had been long-time political enemies. Clay then sought a military appointment, but instead Jefferson Davis appointed him a commissioner to Canada in April 1864. While serving, Clay took part in a series of failed attempts to undermine the U.S. government. First, he embarked on a secret, unsuccessful, mission to secure Democrats in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois as Confederate allies in the run-up to the fall presidential election. He also helped plan a failed attempt to unite representatives of the northern peace faction with Canadian forces to free and arm Confederate prisoners in Camp Douglas, a Confederate prison camp in Chicago.

Finally, he planned with Confederate officer Bennett H. Young to raid St. Albans, Vermont, staging the attack from just over the Canadian Border. On October 19, 1864, Young led a force of 20 soldiers into St. Albans and opened fire on the town. Several citizens were wounded and one was killed. Furloughed Union soldiers quickly assembled the townspeople, however, and chased the raiders back into Canada, where 14 of them were captured by the Canadian military and sent to Montreal for trial. Clay was forced to retain three defense attorneys to assist in their defense and to pay legal fees that reportedly exceeded $80,000. Testimony in the trial placed much of the responsibility for the raid on Clay and raised the possibility that he would be arrested and tried for violating Canada’s neutrality laws.

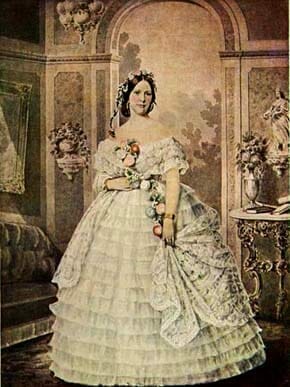

Virginia Tunstall Clay-Clopton

Clay’s health had remained fragile throughout his time in Canada. The strain of the trial was the last straw for him, and he left for home around December 1. After an exhausting and circuitous journey through the federal blockade, he was reunited with his wife at the plantation home of a family friend in Macon, Georgia, on February 10, 1865. The Clays’ next stop was Benjamin Hill’s LaGrange, Georgia, home, where they contemplated how to get through federal lines into Mexico, hoping to join other Confederates who had fled the country after realizing the South would not win the war. Lincoln’s assassination ended their hope for escape. Because of earlier hostile statements he had made about Lincoln while he was in Canada, Clay was implicated in the plot. Upon hearing that a reward of $50,000 was set for his arrest, Clay surrendered to Gen. James H. Wilson, hoping that this act would strengthen his claim of innocence. He was taken into custody and imprisoned in a cell next to Jefferson Davis for a year at Fortress Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. Their wives, Virginia Clay and Varina Davis, finally managed to persuade Pres. Andrew Johnson to release the men on April 18, 1866.

Virginia Tunstall Clay-Clopton

Clay’s health had remained fragile throughout his time in Canada. The strain of the trial was the last straw for him, and he left for home around December 1. After an exhausting and circuitous journey through the federal blockade, he was reunited with his wife at the plantation home of a family friend in Macon, Georgia, on February 10, 1865. The Clays’ next stop was Benjamin Hill’s LaGrange, Georgia, home, where they contemplated how to get through federal lines into Mexico, hoping to join other Confederates who had fled the country after realizing the South would not win the war. Lincoln’s assassination ended their hope for escape. Because of earlier hostile statements he had made about Lincoln while he was in Canada, Clay was implicated in the plot. Upon hearing that a reward of $50,000 was set for his arrest, Clay surrendered to Gen. James H. Wilson, hoping that this act would strengthen his claim of innocence. He was taken into custody and imprisoned in a cell next to Jefferson Davis for a year at Fortress Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. Their wives, Virginia Clay and Varina Davis, finally managed to persuade Pres. Andrew Johnson to release the men on April 18, 1866.

In poor health and financially ruined, Clay returned to Huntsville, where he farmed and returned to his law practice. He died on January 3, 1882, and was buried in Huntsville’s Maple Hill Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama United States Senators by Elbert L. Watson (Huntsville, Ala: Strode Publishers, 1982)