Constitutional Reform

There have been many attempts over the years to reform the 1901 version of Alabama‘s Constitution, which was written to empower industrial and agricultural business interests. Many of the original provisions that were blatantly racist or were aimed at disenfranchising black and poor white voters have been removed, and current efforts focus on repealing provisions that prevent counties from deciding issues of local importance and cripple economic development and on reforming burdensome tax policies. The document, having been amended more than 800 times, remains the longest in the world, containing numerous detailed provisions not found in any other constitution.

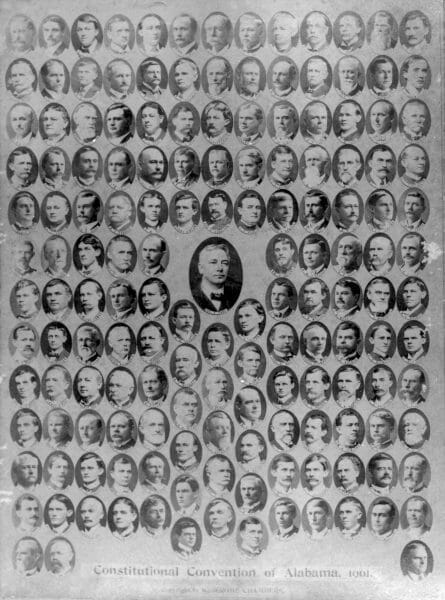

1901 Constitutional Convention

There is a general consensus among political scientists and historians in Alabama that the state’s 1901 Constitution has substantially hindered the state’s progress. Threatened by the growing political power of white tenant farmers, mill workers, miners, and blacks during the late nineteenth century, in 1901 two powerful interest groups, the plantation owners (major land holders concentrated in the Black Belt) and the Big Mules (leaders of the state’s banks, railroads, and industries concentrated in urban areas) created Alabama’s 1901 Constitution. A constitutional convention was held on May 21, 1901, and the document was ratified in a statewide vote in November of that year. The new constitution established white supremacy in the state by denying all blacks and most poor and lower-middle-class whites the right to vote. The Constitution also removed home rule from counties and municipalities and starved funding for public education by establishing an elaborate web of property tax caps that continue to allow the largest landowners, especially big timber corporations (many of which are headquartered out-of-state), to pay extremely low property taxes.

1901 Constitutional Convention

There is a general consensus among political scientists and historians in Alabama that the state’s 1901 Constitution has substantially hindered the state’s progress. Threatened by the growing political power of white tenant farmers, mill workers, miners, and blacks during the late nineteenth century, in 1901 two powerful interest groups, the plantation owners (major land holders concentrated in the Black Belt) and the Big Mules (leaders of the state’s banks, railroads, and industries concentrated in urban areas) created Alabama’s 1901 Constitution. A constitutional convention was held on May 21, 1901, and the document was ratified in a statewide vote in November of that year. The new constitution established white supremacy in the state by denying all blacks and most poor and lower-middle-class whites the right to vote. The Constitution also removed home rule from counties and municipalities and starved funding for public education by establishing an elaborate web of property tax caps that continue to allow the largest landowners, especially big timber corporations (many of which are headquartered out-of-state), to pay extremely low property taxes.

In addition, historians have concluded that the votes needed to ratify this constitution were fraudulently obtained. The collective votes in all the counties, other than the 12 counties in the Black Belt region, would have defeated ratification by a slim margin. The votes cast in the Black Belt counties, each of which were two-thirds black, supported ratification by a huge majority, indicating that these black, landless, and powerless sharecroppers were either intimidated into voting for ratification or that votes favoring ratification were reported without having ever been cast.

Rather than delegate to the counties the ability to exercise police powers to protect their residents in the areas of health, safety, land-use planning, and future growth, elected county commissioners must secure a constitutional amendment, which can result in a statewide vote on what should be a purely a local matter. Counties have, for example, needed constitutional amendments to dispose of dead farm animals and control pests. Constitutional amendments have also been necessary to create incentives to attract new business, thus complicating, delaying, and sometimes thwarting altogether badly needed economic development projects.

The fact that major portions of the state income tax law are embedded in the Constitution is the principal reason why Alabama continues to tax individuals and families who live well below the federal poverty line. Rather than delegate the power over local property taxes to local governments and their residents, the constitution requires amendments for all local property tax increases. The result is that local property tax referendums passed by local residents may fail if they do not get a majority of the required statewide vote. One consequence of this provision is that local governments heavily rely on high sales taxes, which apply even to necessities such as groceries, to fund schools and meet other local needs. In addition to creating a volatile budget, over-reliance on sales taxes contributes greatly to the regressive tax burden experienced by poor and middle-class Alabamians and the chronic underfunding of most of Alabama’s school districts.

In comparison, the U.S. Constitution is the shortest, most effective, and longest lasting constitution in the world largely because it guards fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, free exercise of religion, due process of law, and equal protection without unnecessarily obstructing the ability of Congress and the state legislatures to meet their separate needs. The U.S. Constitution was not intended to be amended often and has only been amended 17 times (not counting the first 10 amendments which make up the Bill of Rights) since it was written.

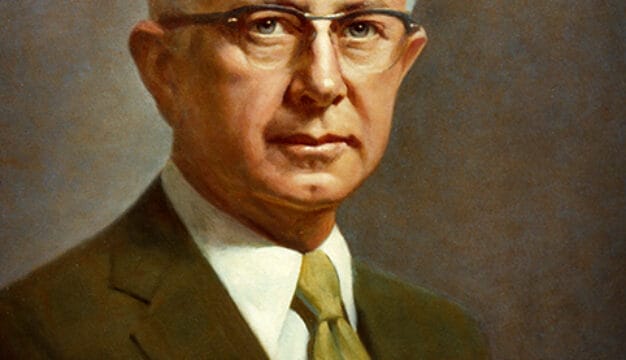

Albert P. Brewer

In the twentieth century, five governors recognized the need to revise or replace Alabama’s 1901 Constitution, starting with Emmet O’Neal in 1915 and Thomas Kilby in 1923. In the 1940s and 1950s, reform efforts by James E. “Big Jim” Folsom and in 1979 by Forrest “Fob” James Jr. failed largely because of heavy lobbying from special interest groups. Gov. Albert Brewer‘s attempt to usher in constitutional reform through an appointed commission failed when he was defeated by George C. Wallace in 1971. Lt. Governor Bill Baxley’s 1983 attempt to offer the voters a chance to approve a new constitution was killed by the Alabama Supreme Court. In recent years, the highest profile organized opponents of constitutional reform are the Alabama Eagle Forum and Alabama Farmer’s Association (ALFA), claiming that constitutional reform will result in tax increases.

Albert P. Brewer

In the twentieth century, five governors recognized the need to revise or replace Alabama’s 1901 Constitution, starting with Emmet O’Neal in 1915 and Thomas Kilby in 1923. In the 1940s and 1950s, reform efforts by James E. “Big Jim” Folsom and in 1979 by Forrest “Fob” James Jr. failed largely because of heavy lobbying from special interest groups. Gov. Albert Brewer‘s attempt to usher in constitutional reform through an appointed commission failed when he was defeated by George C. Wallace in 1971. Lt. Governor Bill Baxley’s 1983 attempt to offer the voters a chance to approve a new constitution was killed by the Alabama Supreme Court. In recent years, the highest profile organized opponents of constitutional reform are the Alabama Eagle Forum and Alabama Farmer’s Association (ALFA), claiming that constitutional reform will result in tax increases.

A more recent reform effort, sponsored by the West Alabama Chamber of Commerce commemorating their 100th anniversary, began on April 7, 2000, at the ruins of the old state capital in Tuscaloosa, when the group Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform (ACCR) was created. ACCR is dedicated to educating Alabamians about how the current Constitution prevents residents of local areas from deciding local issues, cripples economic development, and enshrines taxes that are unfairly burdensome on the poor and middle classes. The organization also aims to help Alabamians push the legislature to support a new state constitution. Supporters of constitutional reform working with ACCR strongly favor drafting a totally new document that completely replaces the old document through the process of a constitutional convention, a formal statewide meeting of delegates elected to craft a new constitution. Others, however, favor an article-by-article revision of the constitution, which, in addition to approaching the project in a piecemeal fashion, would empower the legislature rather than delegates, to determine the changes offered to the voters.

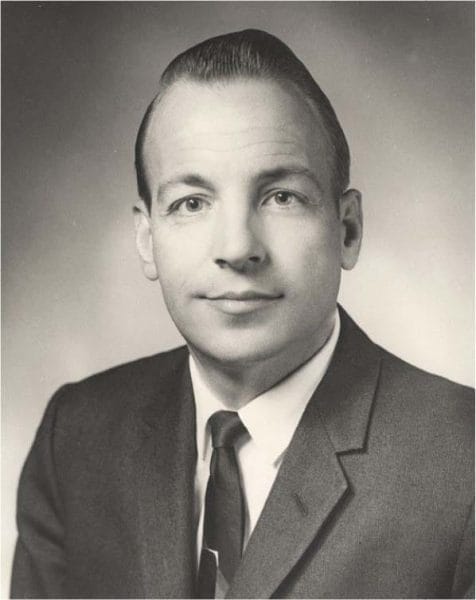

Bob Riley in Mobile

Under its first chair, Thomas Corts, then-president of Samford University, ACCR organized more rallies and conferences and established the Alabama Citizens Commission on Constitutional Reform to develop recommendations for substantive revisions to the state Constitution. The 22-member commission, chaired by then-Secretary of State Jim Bennett, received advice from a group of 15 lawyers, political science and history scholars, and other qualified experts about how a new constitution should address the state’s many problems. These individuals presented 13 working papers that analyzed local self-government, public education, taxation and debt, economic development, and other issues. The commission prepared a report recommending changes, which was presented to Gov. Bob Riley in March 2003. Shortly after receiving this report, Riley, who favored an article-by-article revision, appointed 35 individuals to the Alabama Citizens Constitution Commission to examine certain areas including home rule. Little came from this effort toward advancing the goals of constitutional reformers, however.

Bob Riley in Mobile

Under its first chair, Thomas Corts, then-president of Samford University, ACCR organized more rallies and conferences and established the Alabama Citizens Commission on Constitutional Reform to develop recommendations for substantive revisions to the state Constitution. The 22-member commission, chaired by then-Secretary of State Jim Bennett, received advice from a group of 15 lawyers, political science and history scholars, and other qualified experts about how a new constitution should address the state’s many problems. These individuals presented 13 working papers that analyzed local self-government, public education, taxation and debt, economic development, and other issues. The commission prepared a report recommending changes, which was presented to Gov. Bob Riley in March 2003. Shortly after receiving this report, Riley, who favored an article-by-article revision, appointed 35 individuals to the Alabama Citizens Constitution Commission to examine certain areas including home rule. Little came from this effort toward advancing the goals of constitutional reformers, however.

ACCR’s activities brought some traction to the reform movement, but it briefly faltered after the November 2003 death of Bailey Thomson. A University of Alabama professor and journalist, he had helped organize ACCR in 2000 and secure valuable support from the state’s newspapers. The advocacy arm of ACCR has continued to push for bills in the Alabama State Legislature that would allow state residents to vote on the creation of a constitutional convention. These bills have either failed in committee or on the floor of the House of Representatives. In February 2009, ACCR suffered another setback with the death of Corts.

In 2011, the Alabama legislature convened the Constitutional Revision Commission to review 11 of the document’s 18 articles, exclusive of tax issues, and recommend revisions over a three-year period. Chaired by former governor Albert Brewer, the panel consisted of members of the legislature, representatives of the legal profession, and others. It was largely unsuccessful in producing meaningful change, however. In 2012, a ballot initiative to revise the constitution to change the system of funding education and to remove racist language from the document overwhelmingly defeated by voters. Several bills introduced in recent legislative sessions that would have led to possible revisions died in the legislature. The Alabama Supreme Court has questioned the legality of the piecemeal approach. In 2016, the Constitutional Revision Commission under Brewer’s leadership helped pass four constitution amendments incrementally advancing constitutional reform. The death of Brewer on January 2, 2017, deprived the constitutional reform movement and the state of Alabama of a great leader.

Additional Resources

Brewer, Albert P. “A Broad Initiative: Alabama’s Citizens’ Commission on Constitutional Reform.” Cumberland Law Review 33 (2002-2003): 187-93.

Brewer, Albert P., and Charles D. Cole. Alabama Constitutional Law. Birmingham: Samford Univesity Press, 1992.

Hamill, Susan Pace. The Least of These: Fair Taxes and the Moral Duty of Christians. Raliegh, N.C.: Sweetwater Press, 2003.

McCrary, Latasha L. “Suffering from Past Evils: How Alabama’s 1901 Constitution Played a Hand in the 2008 Presidential Election.” Berkeley Journal of African-American Law & Policy 12 (April 2013): 4-32.

McCurly, Robert L., Jr., and Keith Norman. Alabama Legislation. Tuscaloosa: The Alabama Law Institute, 1997.

McMillan, Malcolm Cook. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

Stewart, William H. Jr. The Alabama Constitutional Commission: A Pragmatic Approach to Constitutional Revision. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1975.

Thomson, Bailey, ed. A Century of Controversy: Constitutional Reform in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.