Joe Cain

Joe Cain (1832-1904) is regarded as the founder of Mobile‘s modern-day Mardi Gras celebration. In 1866, Cain paraded through downtown Mobile dressed as an imagined Indian chief, an act that helped rejuvenate the city’s carnival tradition after the Civil War. Today, revelers commemorate Cain’s role in reviving the celebration with a large public parade first held in the early 1960s.

Joe Cain

Joseph Stillwell Cain was born in Mobile, Mobile County, on October 10, 1832. His parents had moved to Mobile from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1825. From an early age, Cain was enamored of the various social organizations in the city. At 13, he became a charter member of the Tea Drinkers Society (TDS), one of several social clubs, known as mystic societies, that paraded on New Year’s Eve. Prior to the Civil War, Mardi Gras was celebrated in conjunction with festivities to ring in the New Year. The outbreak of the Civil War ended these celebrations as a blockade strangled off trade in Mobile. In April 1865, Union troops took control of the city. Like many young Alabamians, Cain fought in the war, serving as a private in the Confederate Army until 1864. After his service ended, he lived briefly in New Orleans, where he participated in that city’s Mardi Gras festivities.

Joe Cain

Joseph Stillwell Cain was born in Mobile, Mobile County, on October 10, 1832. His parents had moved to Mobile from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1825. From an early age, Cain was enamored of the various social organizations in the city. At 13, he became a charter member of the Tea Drinkers Society (TDS), one of several social clubs, known as mystic societies, that paraded on New Year’s Eve. Prior to the Civil War, Mardi Gras was celebrated in conjunction with festivities to ring in the New Year. The outbreak of the Civil War ended these celebrations as a blockade strangled off trade in Mobile. In April 1865, Union troops took control of the city. Like many young Alabamians, Cain fought in the war, serving as a private in the Confederate Army until 1864. After his service ended, he lived briefly in New Orleans, where he participated in that city’s Mardi Gras festivities.

Excelsior Band at Joe Cain’s Grave, 1967

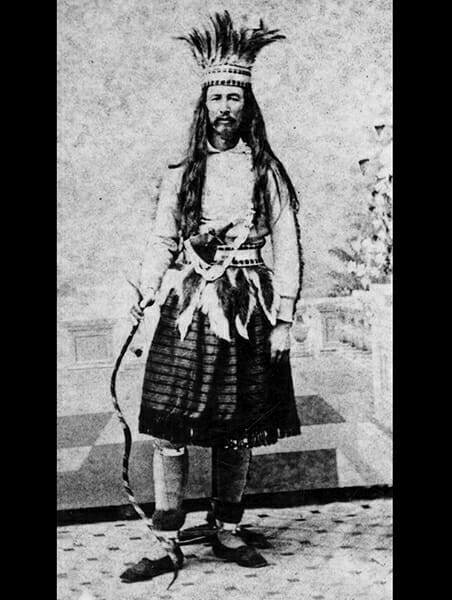

In 1866, Cain returned to Mobile and decided to revive the spirit of Mobile’s New Year’s Eve festivities during the more traditional pre-Lenten period observed in New Orleans. Cain and six original members of TDS rode through Mobile’s streets in a decorated charcoal wagon. The members of the troupe dressed in exaggerated Indian attire, and Cain led the impromptu parade dressed as a fictional Chickasaw chieftain named Slackabamarinico. Along their route, Cain exuberantly declared an end to Mobile’s suffering and signaled the return of the city’s parading activities, to the delight of local residents. His actions also succeeded in moving Mobile’s celebration to the traditional Fat Tuesday. In 1867, Cain led a parade of 16 former Confederate soldiers who called themselves the Lost Cause Minstrels. Because of this troupe, the mythology of the Lost Cause would become a central part of Mobile’s Mardi Gras festivities for many years thereafter. Cain was one of the founding members of the Order of Myths, and the society’s emblem, Folly chasing Death around a broken column, is seen by many as another invocation of the mythology of the Lost Cause.

Excelsior Band at Joe Cain’s Grave, 1967

In 1866, Cain returned to Mobile and decided to revive the spirit of Mobile’s New Year’s Eve festivities during the more traditional pre-Lenten period observed in New Orleans. Cain and six original members of TDS rode through Mobile’s streets in a decorated charcoal wagon. The members of the troupe dressed in exaggerated Indian attire, and Cain led the impromptu parade dressed as a fictional Chickasaw chieftain named Slackabamarinico. Along their route, Cain exuberantly declared an end to Mobile’s suffering and signaled the return of the city’s parading activities, to the delight of local residents. His actions also succeeded in moving Mobile’s celebration to the traditional Fat Tuesday. In 1867, Cain led a parade of 16 former Confederate soldiers who called themselves the Lost Cause Minstrels. Because of this troupe, the mythology of the Lost Cause would become a central part of Mobile’s Mardi Gras festivities for many years thereafter. Cain was one of the founding members of the Order of Myths, and the society’s emblem, Folly chasing Death around a broken column, is seen by many as another invocation of the mythology of the Lost Cause.

Cain worked in various jobs in Mobile throughout his life. Soon after the war, he returned to his position as a cotton broker. But the post-war cotton market was never as prosperous as it was during the antebellum period, and Cain, like many others, soon moved on to other professions. He served as a volunteer fireman and briefly worked in the Mobile coroner’s office. During his later years, Cain worked as a clerk at Mobile’s Southern Market, a large produce and meat market located on the ground floor of the stately City Hall, a building that now houses the History Museum of Mobile. Later in his life, he and his wife moved to Bayou la Batre to live with his son. Cain’s resurrection of Mobile’s season of revelry was widely admired, and he remained a favorite at local festivities for the rest of his life. Cain died on April 17, 1904, and was buried in Oddfellow’s Cemetery, outside Bayou La Batre.

Joe Cain’s Grave

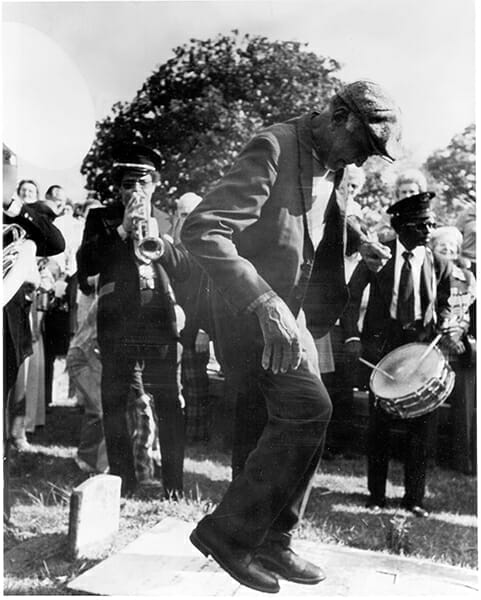

For more than a half century after Cain’s death, Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration remained a popular but exclusive celebration. The mystic societies had closed memberships, leaving most revelers with little to do but watch the merriment from the sidewalks. This began to change in the 1960s when Julian Lee Rayford, a local author, set out to make the event more inclusive and to honor Joe Cain. In 1966, Rayford convinced city officials to exhume the bodies of Joe Cain and his wife and move them to the Church Street Graveyard, Mobile’s oldest existing cemetery. Cain was interred with all the pomp and revelry of a Mardi Gras parade, with a jazz-band procession and throngs of mourners. His granite tombstone, incised with the image of a jester, reads: “Here Lies Old Joe Cain, the Heart and Soul of Mardi Gras in Mobile.”

Joe Cain’s Grave

For more than a half century after Cain’s death, Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration remained a popular but exclusive celebration. The mystic societies had closed memberships, leaving most revelers with little to do but watch the merriment from the sidewalks. This began to change in the 1960s when Julian Lee Rayford, a local author, set out to make the event more inclusive and to honor Joe Cain. In 1966, Rayford convinced city officials to exhume the bodies of Joe Cain and his wife and move them to the Church Street Graveyard, Mobile’s oldest existing cemetery. Cain was interred with all the pomp and revelry of a Mardi Gras parade, with a jazz-band procession and throngs of mourners. His granite tombstone, incised with the image of a jester, reads: “Here Lies Old Joe Cain, the Heart and Soul of Mardi Gras in Mobile.”

Cain’s Merry Widows

Cain’s reburial drew such a large crowd that Rayford and others decided to create an annual event celebrating Cain, held the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. They instituted the Joe Cain Day Parade (also known as The People’s Parade), which is led by a person dressed as Chief Slackabamarinico. The route concludes in the Church Street Graveyard, and then Mobilians dance atop Cain’s grave and veiled women dressed in mourning, known as Cain’s Merry Widows, cry aloud and lament his loss to the world.

Cain’s Merry Widows

Cain’s reburial drew such a large crowd that Rayford and others decided to create an annual event celebrating Cain, held the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. They instituted the Joe Cain Day Parade (also known as The People’s Parade), which is led by a person dressed as Chief Slackabamarinico. The route concludes in the Church Street Graveyard, and then Mobilians dance atop Cain’s grave and veiled women dressed in mourning, known as Cain’s Merry Widows, cry aloud and lament his loss to the world.

Joe Cain Day remains one of the most popular events of Mobile’s Mardi Gras celebration, and its public parade is seen by many Mobilians as a response to the stiffness of the traditional mystic societies. Every year, thousands of revelers inhabit the spirit of Joseph Stillwell Cain and, at least for a few days, forget their troubles during Mobile’s Mardi Gras season.

Additional Resources

Dean, Wayne. Mardi Gras: Mobile’s Illogical Whoop-De-Do. Chicago: Adams Press, 1967.

Kinser, Samuel. Carnival, American Style: Mardi Gras at Mobile and New Orleans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Mardi Gras Vertical Files, Mobile Public Library Local History and Genealogy Section, Mobile, Alabama.

Pond, Ann J. “The Ritualized Construction of Status: The Men Who Made Mardi Gras, 1830-1900.” Ph.D. diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 2006.

Rayford, Julian Lee. Chasin’ the Devil Round a Stump. Mobile, Ala.: American Printing Company, 1962.