Ellen Dorrit Hoffleit

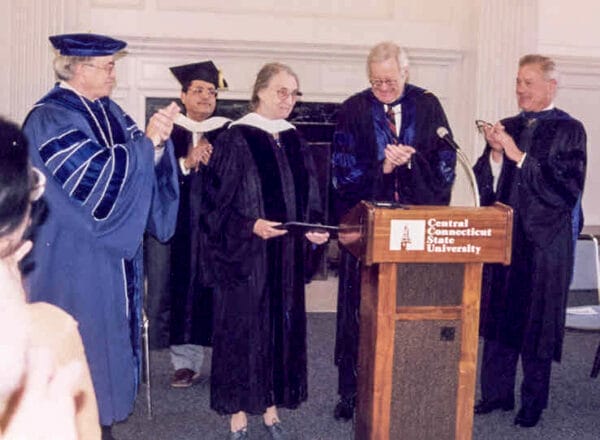

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1998

Astronomer, educator, and science historian Dorrit Hoffleit (1907-2007) was widely respected by the amateur and professional astronomical community as a mentor and an ardent supporter of independent research. Her more than 600 catalogues, books, articles, book reviews, and news columns cover myriad aspects of astronomy, from variable stars (stars that change brightness over time) and stellar properties to meteor showers, quasars, and rocketry. She also made important contributions to the history of astronomy, especially on the role and work of women in the field.

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1998

Astronomer, educator, and science historian Dorrit Hoffleit (1907-2007) was widely respected by the amateur and professional astronomical community as a mentor and an ardent supporter of independent research. Her more than 600 catalogues, books, articles, book reviews, and news columns cover myriad aspects of astronomy, from variable stars (stars that change brightness over time) and stellar properties to meteor showers, quasars, and rocketry. She also made important contributions to the history of astronomy, especially on the role and work of women in the field.

The daughter of Fred and Kate (Sanio) Hoffleit, two German immigrants, Ellen Dorrit Hoffleit was born on March 12, 1907, in a log cabin on her father’s farm in Florence, Lauderdale County. Her mother raised the infant Dorrit and her older brother, Herbert, by herself for the first nine months of Dorrit’s life because her father had to return to his previous job as a bookkeeper at the Pennsylvania Railroad in New Castle, Pennsylvania, to support his family. The family was reunited in Pennsylvania after the cabin was destroyed in a suspicious fire, but when Dorrit was nine years old her father returned to his farm alone, and her parents’ marriage dissolved.

As a child, Dorrit enjoyed stargazing with her mother and brother (especially watching meteor showers) but always felt she was in her brilliant brother’s shadow. The family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, so that Herbert could attend Harvard University, and Dorrit attended Radcliffe College (now part of Harvard), so that she would not (in her mother’s words) be an embarrassment to her brother. Ironically, Dorrit would greatly surpass her brother, a classics scholar at the University of California Los Angeles, in both career success and accolades throughout her lengthy career.

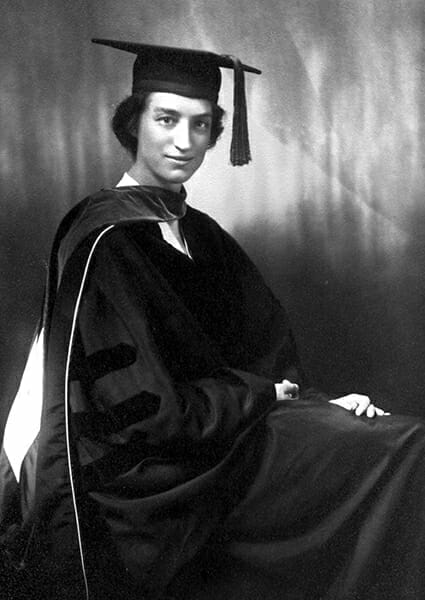

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1938

After completing her mathematics degree at Radcliffe in 1928, Hoffleit took a job as a research assistant at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). She had taken two astronomy courses in college and chose the relatively low-paying job at HCO (40 cents an hour) over a higher paying statistician job because she found the work at HCO more interesting. She completed an M.A. in astronomy at Radcliffe in 1932 and would have been content to remain in her position with no further education had HCO director Harlow Shapley not read her independent research on the light curves of meteor showers and urged her to go on for a Ph.D., which she completed in 1938.

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1938

After completing her mathematics degree at Radcliffe in 1928, Hoffleit took a job as a research assistant at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). She had taken two astronomy courses in college and chose the relatively low-paying job at HCO (40 cents an hour) over a higher paying statistician job because she found the work at HCO more interesting. She completed an M.A. in astronomy at Radcliffe in 1932 and would have been content to remain in her position with no further education had HCO director Harlow Shapley not read her independent research on the light curves of meteor showers and urged her to go on for a Ph.D., which she completed in 1938.

Hoffleit remained at Harvard as a research associate and astronomer until 1956, working with the observatory’s vast collection of photographs and other astronomical data. She published original research in such diverse areas as variable stars (more than 1,200 of which she discovered herself), novae, and absolute magnitudes (a measure of a star’s true brightness regardless of its distance from us). She also began working in the history of astronomy and wrote numerous articles for popular astronomy magazines, including a column in Sky and Telescope from 1941 to 1956. During World War II and for several years afterwards, Hoffleit worked at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, preparing detailed tables of calculations that were used to correctly aim artillery and other weapons; while there, she found herself the victim of open and obvious gender discrimination. She recounted in numerous autobiographical articles and interviews that her fight to get the job level her credentials merited was one of the defining moments of her career.

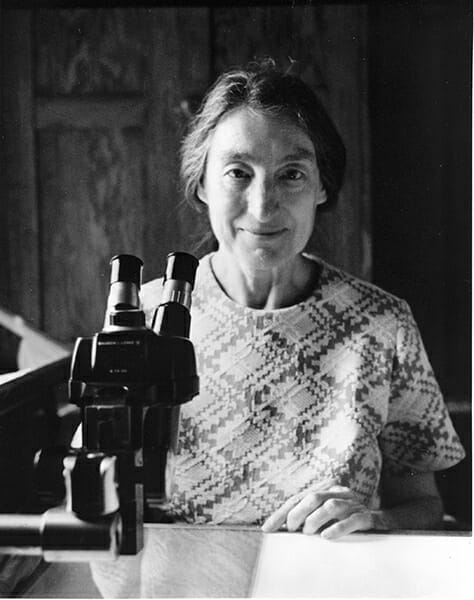

Dorrit Hoffleit at the Mitchell Observatory

When Shapley retired from Harvard, Dorrit was faced with a life-changing decision. Shapley had always encouraged Dorrit and her colleagues to work independently and creatively, but his replacement, Donald Menzel, was not so encouraging or supportive. In addition, he began discarding large sections of Harvard’s historical photographic plate collection in the name of saving space. Hoffleit therefore gave up her tenured position at Harvard and moved to Yale University, where she was placed in charge of several large catalogue projects, particularly the Catalog of Bright Stars. These publications contained detailed information about thousands of stars, including each star’s distance, brightness, and movement through space, and continue to be vital references for astronomers around the world. At the same time, she was offered a position as director of the Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket Island in Massachusetts, a facility based at the home of America’s first woman astronomer, Maria Mitchell. Hoffleit was able to split her dual positions into six-month stints and remained director at the Mitchell Observatory for 21 years. During this time, she developed a summer research program that engaged more than 100 Yale undergraduate students (all but three of them women) in variable star research; the program continues to this day.

Dorrit Hoffleit at the Mitchell Observatory

When Shapley retired from Harvard, Dorrit was faced with a life-changing decision. Shapley had always encouraged Dorrit and her colleagues to work independently and creatively, but his replacement, Donald Menzel, was not so encouraging or supportive. In addition, he began discarding large sections of Harvard’s historical photographic plate collection in the name of saving space. Hoffleit therefore gave up her tenured position at Harvard and moved to Yale University, where she was placed in charge of several large catalogue projects, particularly the Catalog of Bright Stars. These publications contained detailed information about thousands of stars, including each star’s distance, brightness, and movement through space, and continue to be vital references for astronomers around the world. At the same time, she was offered a position as director of the Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket Island in Massachusetts, a facility based at the home of America’s first woman astronomer, Maria Mitchell. Hoffleit was able to split her dual positions into six-month stints and remained director at the Mitchell Observatory for 21 years. During this time, she developed a summer research program that engaged more than 100 Yale undergraduate students (all but three of them women) in variable star research; the program continues to this day.

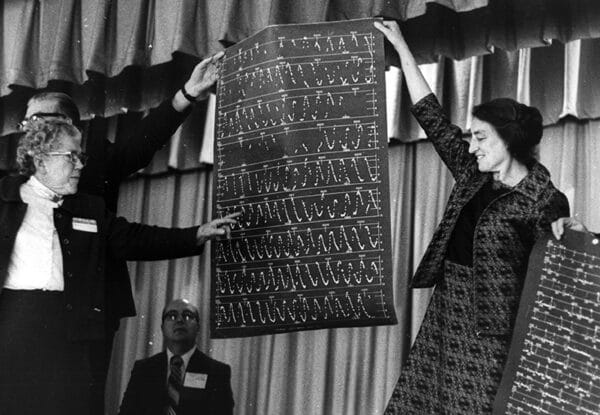

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1973

During her years at Yale, Hoffleit continued various research projects as an untenured research associate and later astronomer (supported entirely through grants), even after her official retirement in 1975. Up until shortly before her death, she continued to work tirelessly at Yale on selected projects, and she remained in high demand as a collaborator with colleagues at Yale and elsewhere. After 1983, she devoted a significant portion of her time to researching the history of astronomy, producing numerous presentations and articles, a book entitled Astronomy at Yale 1701-1968, and several short monographs published by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). She was especially devoted to this astronomical organization in part because it brought together amateur and professional astronomers in collaboration. She served on the organization’s council for 23 years and as its president from 1961 to 1963. In 2002, the AAVS0 published her autobiography, Misfortunes As Blessings In Disguise, in which Hoffleit discusses her attitude toward life. As the title suggests, Dorrit always felt blessed by the opportunities in her life, even those which initially seemed misfortunes (such as her decision to leave Harvard), and above all else valued creativity, flexibility, and intellectual freedom in her professional life.

Dorrit Hoffleit, 1973

During her years at Yale, Hoffleit continued various research projects as an untenured research associate and later astronomer (supported entirely through grants), even after her official retirement in 1975. Up until shortly before her death, she continued to work tirelessly at Yale on selected projects, and she remained in high demand as a collaborator with colleagues at Yale and elsewhere. After 1983, she devoted a significant portion of her time to researching the history of astronomy, producing numerous presentations and articles, a book entitled Astronomy at Yale 1701-1968, and several short monographs published by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). She was especially devoted to this astronomical organization in part because it brought together amateur and professional astronomers in collaboration. She served on the organization’s council for 23 years and as its president from 1961 to 1963. In 2002, the AAVS0 published her autobiography, Misfortunes As Blessings In Disguise, in which Hoffleit discusses her attitude toward life. As the title suggests, Dorrit always felt blessed by the opportunities in her life, even those which initially seemed misfortunes (such as her decision to leave Harvard), and above all else valued creativity, flexibility, and intellectual freedom in her professional life.

During the last few decades of her life, she received a number of honors, including honorary doctorates from Smith College in 1984 and Central Connecticut State University in 1998, the Wedgewood Medallion of the Coat of Arms of Yale University (1992), the Annenberg Foundation Award of the American Astronomical Association (1993), the Glover Award of Dickinson College (1995), and the Maria Mitchell Women in Science Award (1997). In 1987, an asteroid was named “Dorrit” in her honor, and in 1998, she was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. Yale University organized two scientific symposia to honor her, one in 1997 to celebrate her 90th birthday, and a second in 2006 in celebration of her centennial year. Her 100th birthday party was celebrated at Yale on March 14, 2007, and she died several weeks later on April 9, her place in astronomical history firmly established. In keeping with her life-long dedication to science, Dorrit donated her body to the Yale University Medical School. Her influence on the astronomical community, both professional and amateur, remains as a lasting legacy.

Additional Resources

Hoffleit, Dorrit. Misfortunes As Blessings In Disguise. Cambridge, Mass.: American Association of Variable Star Observers, 2002.

———. “Some Glimpses From My Career.” Mercury 21 (January/February 1992): 16-19.

Larsen, Kristine. “An Interview with Dorrit Hoffleit.” Journal of the AAVSO 37 (2009): 52-69.