Election Riots of 1874

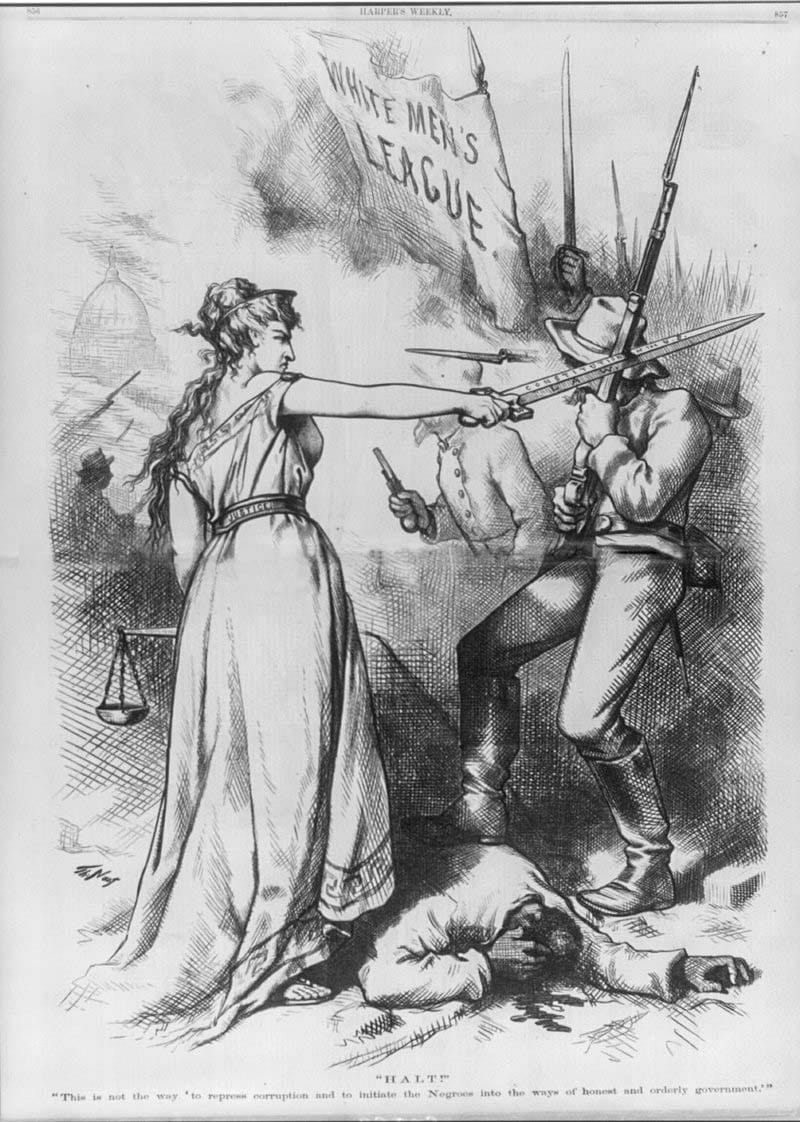

On November 3, 1874, during statewide elections in Alabama, deadly conflicts occurred in the Barbour County cities of Eufaula and Spring Hill, a result of social tensions brought about by Reconstruction Era societal changes. These events, termed “riots” in many histories, were largely White men intimidating and attacking Black voters to prevent them from voting or electioneering. The immediate practical effect was that many Black voters were turned away from the polls in Eufaula and had their ballots burned in Spring Hill. These events also drew national attention and a congressional investigation, and they signaled the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of “redemption” and “Bourbonism” in Alabama: the resumption of the Democratic Party‘s control of state government.

In Eufaula, racial and political tensions were especially high during that election season. Blacks, along with so-called “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags,” had held power for several years. The term carpetbagger refers to individuals who came from other, typically northern, states to Alabama during Reconstruction. Scalawags refers to native Alabamians who sided at the time with or assisted Federal officials and Republicans. Both terms were used negatively by critics of Reconstruction at the time and in later historical writings. During this period, local Democrats felt threatened by Black voting, particularly because Black citizens tended to vote Republican. These Eufaula Democrats had supported secession in the Civil War and frequently feared that freed Blacks would rise up against them. They formed the “White Man’s Club of Eufaula” and other secret organizations ostensibly to defend their rights and perform other functions, which foreshadowed the tone of the fall elections. The group urged Blacks to sign allegiance pledges to the Democratic Party and often applied economic pressure after other inducements were unsuccessful, such as promising work for those who would vote Democratic and unemployment for those who were Republicans.

The Republican nominating convention that August in Clayton, the county seat, was interrupted by armed Democrats and attendees were forced to move to the outskirts of town. Presiding judge Elias Keils, a Republican who was generally disliked by white Democrats, sensed the tension in the area and appealed to Alabama Attorney General Benjamin Gardner for Gov. David P. Lewis (1872-1874) to declare martial law. Keils also appealed to U.S. Marshal R. W. Healy in Montgomery, who responded by sending 20 federal troops and two officers. Military forces, however, were forbidden from becoming involved in elections by Gen. Irwin McDowell’s Order No. 75, which authorized them only to assist federal courts and officials.

On Election Day eve, there may have been as many as 1,000 or more Black men from Barbour County camping out on the outskirts of Eufaula; accounts citing figures vary. In addition, persistent but false rumors of an “invasion” of the city circulated within the White community. Keils and Black leaders such as Aleck Williams, Edward Odum, and Henry Frazier urged the men to come unarmed, and an inspection by a federal soldier uncovered no weapons when they got into town. Local Democratic leader Eli Sims Shorter had requested that Blacks come to the polls in small numbers, but he reported, however, that they arrived in large groups in military formation armed with pistols, clubs, and knives; evidence of the disparity in eyewitness accounts.

Voting began smoothly until an argument arose between Milas Lawrence, a Black Republican, and White Democrat Charles E. Goodwin over an underage Black voter. The young man admitted being underage and was turned away before voting. White Democrats then took that same underaged man into the alley, and the youth agreed to vote Democratic. Lawrence confronted the young man for his choice, and a White man named William Dowdy stabbed Lawrence in the shoulder. Gunfire began almost immediately as Democrats took arms, possibly stored in anticipation of conflict, from a militia storage area above the polls and another location across the street in an organized fashion. Most of the shooting came from Whites as Blacks retreated before they were able to vote. Military records showed that either seven or eight Black men were killed or died later from injuries, and 70 to 80 men were wounded. Fewer than a dozen were White.

In Spring Hill, Judge Keils presided over the polls. At about 11:00 a.m., random gunfire was heard, and approximately 50 Democrats then armed themselves and paraded at the polls throughout the afternoon, attempting to intimidate Black voters. Sensing trouble, Keils sent his 16-year-old son Willie to find Lt. William J. Turner, who was stationed nearby with ten men, but Turner informed Willie that he had been forbidden to intervene. Willie returned to the Spring Hill polls about 5:00 p.m., when the polls closed, so Keils decided to lock the door to protect the ballots and await daylight. At 6:00 p.m., however, a Democratic election official unbolted the door and armed men rushed inside, extinguishing the light and firing into the building. Keils and his son hid behind a counter, but Willie was hit with four bullets, likely intended for his father, and died two days later. When Keils left to find a doctor for his son, the ballot box and more than 700 ballots from the predominantly Black Spring Hill district were taken and burned. A local story later alleged that Keils held up his son to shield himself from the intruders.

Aided by suppression of Black voting in the aftermath of the Eufaula riot and the burned ballots at Spring Hill, Democrats swept the county. After the election, Keils was arrested in Eufaula for carrying a concealed weapon and resisting arrest. He was released to attend U.S. District Court in Montgomery, where he appealed for federal protection but was told that newly elected Democrat governor George H. Houston (1874-1878) had jurisdiction over such matters. He later testified at a congressional investigation into the incident, and by mid-December 1874 he had resigned from the court.

A Barbour County grand jury blamed “militant” local Blacks for increasing tensions in Eufaula, which prompted approximately 40 Whites to arm themselves in self defense, further adding to the already tense atmosphere. The U.S. House of Representatives appointed a special committee to report on affairs in Alabama. The majority Republican committee blamed the Democrats for the incident, whereas the committee’s Democratic minority blamed Republicans and the military for emboldening Black citizens to act without repercussions. Historian Harry Philpot Owen observes that none of these inquiries considered the inevitability of conflict considering the racial view of Whites during this period and the siege mentality created by their fear of Black uprisings. When Blacks dismissed political overtures from Democrats, who had sensed a waning interest in Reconstruction from the North, Democrats sought to offset a vast realignment of society with violence. In other locations throughout the state, looser interpretations of Order No. 75 by local commanders allowed the military to keep peace on Election Day.

Further Reading

- Bailey, Richard. Neither Carpetbaggers nor Scalawags: Black Officeholders during the Reconstruction of Alabama, 1867-1878. Montgomery, Ala.: R. Bailey Publishers, 1991.

- Going, Allen Johnston. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972.

- Hennessey, Melinda M. “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874,” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38 (Summer 1976): 112-125.

- Owen, Harry P. “The Eufaula Riot of 1874,” Alabama Review 16 (July 1963): 224-237.

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfork. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991.