Industrial Baseball Leagues in Alabama

Industrial league baseball was a form of semi-professional baseball that developed during the late nineteenth century and became commonplace in Alabama during much of the twentieth century. Companies sponsored the leagues to enhance employee loyalty and provide entertainment for their workers and families, forming teams made up of players from their own payrolls supplemented by some professionals.

Bessemer Industrial League Baseball Team

In Alabama, the trend developed along two lines—industrial leagues in urban areas and company teams (coal mines, cotton mills, and so on) in more isolated rural areas—with both limiting their competition to teams that were geographically close. The strongest industrial league in Alabama was the Birmingham Industrial League, composed of companies working mostly in Birmingham’s iron and steel industry. Reflecting the segregated society of the day, many companies financed separate white and black teams to reach out to both segments of the community. The powerhouse of all the industrial teams in Birmingham was American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO). ACIPCO’s biggest rival was the Stockham Valves and Fittings company, which it often battled for the annual Industrial League championship. Games between the two teams would sometimes draw 8,000 to 12,000 spectators. The Clow Pipe Company also fielded talented teams, as did Connor Steel, L&N Railroad, Perfection Mattress (whose team later became the 24th Street Red Sox), Sloss Furnace, and Pullman Stanley. Both Willie Mays and his father played in the same outfield during one season with the Fairfield Stars.

Bessemer Industrial League Baseball Team

In Alabama, the trend developed along two lines—industrial leagues in urban areas and company teams (coal mines, cotton mills, and so on) in more isolated rural areas—with both limiting their competition to teams that were geographically close. The strongest industrial league in Alabama was the Birmingham Industrial League, composed of companies working mostly in Birmingham’s iron and steel industry. Reflecting the segregated society of the day, many companies financed separate white and black teams to reach out to both segments of the community. The powerhouse of all the industrial teams in Birmingham was American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO). ACIPCO’s biggest rival was the Stockham Valves and Fittings company, which it often battled for the annual Industrial League championship. Games between the two teams would sometimes draw 8,000 to 12,000 spectators. The Clow Pipe Company also fielded talented teams, as did Connor Steel, L&N Railroad, Perfection Mattress (whose team later became the 24th Street Red Sox), Sloss Furnace, and Pullman Stanley. Both Willie Mays and his father played in the same outfield during one season with the Fairfield Stars.

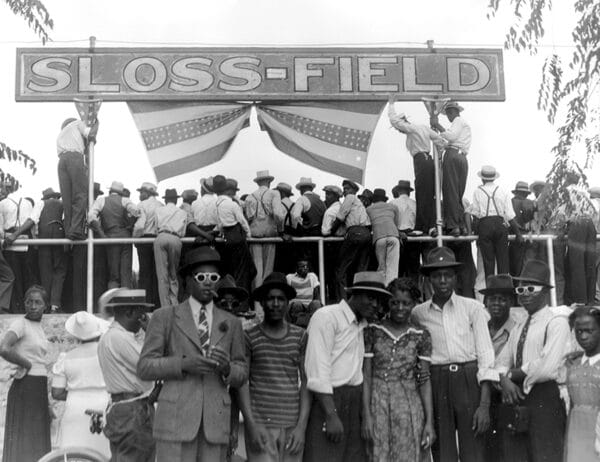

Eight to ten teams typically competed during any specific season, but the total number of different teams from the 1920s through the 1940s exceeded three dozen. Teams would typically play in two divisions (Red and Blue) with an official season of 20 to 25 games. The two division leaders would meet in an end-of-the-season championship game. Major teams would also play up to 60 games against non-league opponents each year. Most games in the Birmingham area were played at Sloss Field, but ACIPCO and Stockham Valve both had fields for their home games. Another field was located in the Titusville area of Birmingham.

Eight to ten teams typically competed during any specific season, but the total number of different teams from the 1920s through the 1940s exceeded three dozen. Teams would typically play in two divisions (Red and Blue) with an official season of 20 to 25 games. The two division leaders would meet in an end-of-the-season championship game. Major teams would also play up to 60 games against non-league opponents each year. Most games in the Birmingham area were played at Sloss Field, but ACIPCO and Stockham Valve both had fields for their home games. Another field was located in the Titusville area of Birmingham.

During World War II, when most of baseball’s minor leagues shut down, Mobile also established an industrial league with two divisions. The Industrial Division included teams from the Alcoa aluminum factory, Alabama Ship Yard, and Gulf Ship Yard. The Service Division fielded military teams from Brookley Air Base, Barin Field, and the U.S. Coast Guard.

These leagues and teams provided both entertainment and employment opportunities. Factory workers and miners worked hard all week and then faced limited entertainment options on the weekends. Local teams played two or three games a week, with each game becoming a major social event. Holidays were particularly festive; on Labor Day and the Fourth of July, for example, companies might sponsor a cookout before the games. Industrial leagues also provided lucrative employment opportunities for young athletes, who were hired by the company to do odd jobs during the week and essentially paid to play baseball on the weekends. Many players earned good incomes by the standards of the day. If they stayed with the company, rather than joining a professional team, they often had a job for life.

Other players used the industrial league as a stepping stone to minor league baseball, and from there to the major leagues. One reason that so many major-league ballplayers came out of the South and out of Alabama during the first half of the twentieth century was that these leagues enabled teenagers to play with grown men and against good teams, a perfect recipe for developing young talent.

Because some industrial league players were former professionals who had returned to the security of a job near their homes, the level of competition sometimes rivaled that of the major leagues. Some teams might have two, three, or more ex-major league players on their squad. Further, former pro players often took jobs managing the local teams. Whereas playing for such a team would be viewed as a demotion for modern players, that stigma did not exist before 1950; companies often paid higher salaries than many players could make in the major leagues.

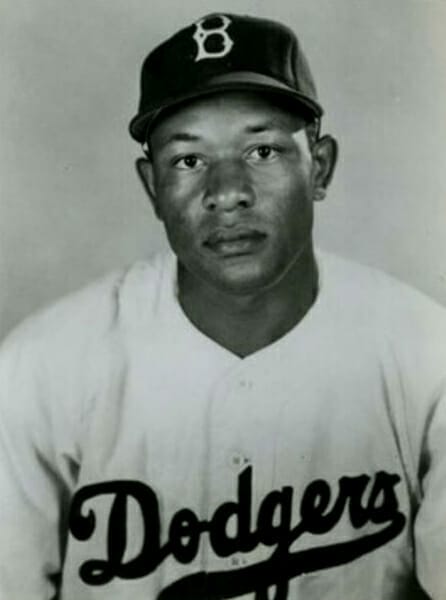

Dan Bankhead

Most industrial league players were recruited from the sand lots and street teams of poor areas in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Scouts for the local teams would visit local youth games, looking to sign a talented teenager for their company. The industrial teams, in turn, provided a feeder system to the major leagues for white players and to the Negro Leagues for African Americans. For African Americans, in particular, the industrial leagues were considered the Negro minor leagues. Negro Leaguer Elmer Knox, a native of Anniston who became a member of the Atlanta Black Crackers, got his start in the steel industry. Knox reportedly said that the steel industry was responsible for developing more players that any other industry in the country. In Alabama, those included Negro League notables Lorenzo “Piper” Davis and the five Bankhead brothers. Dan Bankhead eventually made the major leagues in 1947, becoming the second African American player with the Brooklyn Dodgers. His roommate was Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson.

Dan Bankhead

Most industrial league players were recruited from the sand lots and street teams of poor areas in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Scouts for the local teams would visit local youth games, looking to sign a talented teenager for their company. The industrial teams, in turn, provided a feeder system to the major leagues for white players and to the Negro Leagues for African Americans. For African Americans, in particular, the industrial leagues were considered the Negro minor leagues. Negro Leaguer Elmer Knox, a native of Anniston who became a member of the Atlanta Black Crackers, got his start in the steel industry. Knox reportedly said that the steel industry was responsible for developing more players that any other industry in the country. In Alabama, those included Negro League notables Lorenzo “Piper” Davis and the five Bankhead brothers. Dan Bankhead eventually made the major leagues in 1947, becoming the second African American player with the Brooklyn Dodgers. His roommate was Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson.

Some critics cited industrial-league and company-sponsored baseball as examples of corporate paternalism in which companies used the sport as a way to manage their workers’ behavior and manipulate their attitudes toward work. Some also labeled it as a modern form of slavery or a form of welfare capitalism, arguing that the companies financed the teams rather than paying higher wages to workers with little education. Others disagreed, arguing that the teams had a positive impact by increasing employee identification with that company and providing entertainment for the workers and their families. The large crowds that attended the games, which were often larger than those of the minor league Birmingham Barons, demonstrated their popularity.

During its existence, industrial baseball was an integral part of many Alabama communities, leading many companies to develop teams that rivaled professional teams in terms of both talent and salaries, and the players became heroes to the other workers in the company. The popularity of the industrial leagues waned as the integration of the major leagues led to a decline in both talent and local interest, and national broadcasts of major league games offered a higher profile alternative for fans. Some remnants of the industrial leagues remain in the form of city recreational teams, although many shifted to playing softball.

Additional Resources

Cuhaj, Joe, and Tamra Carraway-Hinckle. Baseball in Mobile. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

Einstein, Charles. Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age. Peoria: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979.

Fullerton, Christopher D. Every Other Sunday. Birmingham, Ala.: R. Boozer Press, 1999.

Hall, Jacquelyn, et al. Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987.

Norrell, Robert J. “Caste in Steel: Jim Crow Careers in Birmingham, Alabama.” Journal of American History 73 (December 1986): 669-692.

Powell, Larry. Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and its Players. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2009.

Rhoden, William C. $40 Million Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete. New York: Crown, 2006.

White, Margorie. The Birmingham District: An Industrial History and Guide. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society, 1981.