Asa Carter (Forrest Carter)

Asa Carter (1925-1979) is remembered as a promoter of white supremacist views, especially in his role as a speech writer for Alabama governor George C. Wallace; he is responsible for Wallace’s infamous 1963 inaugural speech, which included the line “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!” After an unsuccessful run for governor in 1970, he left the state and took on a new identity as Bedford Forrest Carter, authoring several Western adventure novels popularized by Hollywood, most notably as The Outlaw Josey Wales. He also wrote a nationally acclaimed work for young readers, The Education of Little Tree, which he claimed as autobiographical but was later exposed as a hoax.

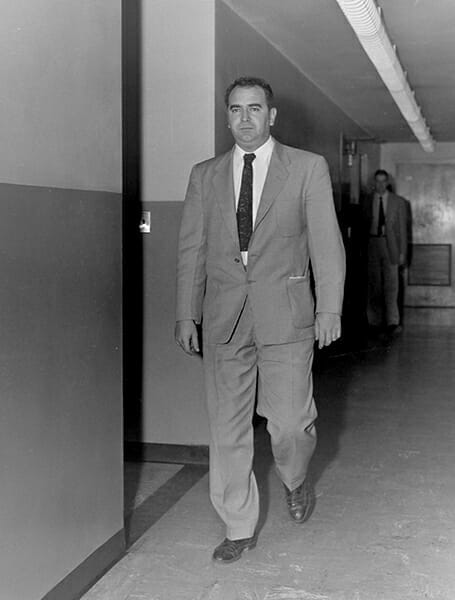

Asa Carter, 1957

Asa Earl Carter, second son of the four children of Ralph and Hermione Carter, was born in Oxford, near Anniston in Calhoun County, on September 4, 1925. He graduated from Calhoun County High School in 1943. Carter served in the U.S. Navy from May 1943 to March 1946 and then married his high-school sweetheart, India Thelma Walker, with whom he had four children. Carter studied journalism at the University of Colorado, and then returned with his family to Birmingham, where he pursued a career in radio. In 1953, he began working as a commentator at Birmingham radio station WILD, broadcasting anti-Semitic and racist speeches to an audience who already adamantly opposed the expanding civil rights movement in Birmingham. Carter also wrote and published The Southerner, a white supremacist magazine, during the 1950s. In addition to his hate-filled broadcasts, Carter also joined with a group of men to found a white supremacist paramilitary organization, the original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy. Members of the group (although not in the company of Carter) were responsible for beating singer Nat “King” Cole in Birmingham in 1956 and for the castration of an African American man in 1957. That same year, Carter was charged in the shooting of two other members of his Klan group over monetary disputes, but the charges were eventually dropped.

Asa Carter, 1957

Asa Earl Carter, second son of the four children of Ralph and Hermione Carter, was born in Oxford, near Anniston in Calhoun County, on September 4, 1925. He graduated from Calhoun County High School in 1943. Carter served in the U.S. Navy from May 1943 to March 1946 and then married his high-school sweetheart, India Thelma Walker, with whom he had four children. Carter studied journalism at the University of Colorado, and then returned with his family to Birmingham, where he pursued a career in radio. In 1953, he began working as a commentator at Birmingham radio station WILD, broadcasting anti-Semitic and racist speeches to an audience who already adamantly opposed the expanding civil rights movement in Birmingham. Carter also wrote and published The Southerner, a white supremacist magazine, during the 1950s. In addition to his hate-filled broadcasts, Carter also joined with a group of men to found a white supremacist paramilitary organization, the original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy. Members of the group (although not in the company of Carter) were responsible for beating singer Nat “King” Cole in Birmingham in 1956 and for the castration of an African American man in 1957. That same year, Carter was charged in the shooting of two other members of his Klan group over monetary disputes, but the charges were eventually dropped.

In the early 1960s, Carter began working as a speech writer for Wallace and continued in that capacity when Wallace’s wife, Lurleen, took office. While enjoying the support that Carter’s white supremacist speeches garnered, Wallace kept his connection with Carter out of the public eye and often publicly denied Carter’s hand in writing them. In the 1968 gubernatorial race, Carter broke his ties with Wallace because of what he viewed as a toning-down of Wallace’s racist rhetoric. Carter then ran for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1970, using thinly veiled racist language and imagery, such as using “busing” as a code word for “integration,” to garner support. He lost badly to the more moderate Wallace.

Carter moved to Florida in 1973 and soon after changed his name to Bedford Forrest Carter in honor of Confederate general and early Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest. He and his wife then moved to Abilene, Texas, where he began working on what would become his first novel, Gone to Texas (originally published as The Rebel Outlaw, Josey Wales in 1973). In it, Carter introduces the character Josey Wales, a former Confederate soldier who also would be the protagonist of Carter’s second novel, The Vengeance Trail of Josey Wales (1976). Both tell tales of revenge and resistance to governmental authority. Wales is consistent in mindset with disillusioned segregationists and states’ rights advocates, refusing to surrender after the Civil War and attempts to evade the pro-Union guerillas who killed his family and who seek to bring him to justice for waging guerilla warfare on federal troops. In 1976, Clint Eastwood played the lead in the film The Outlaw Josey Wales, which was based on the two books. In these novels, Carter depicts southerners and Indians as honorable and loyal, in contrast to the U.S. Army forces and the federal government, who are domineering and remorseless in their behavior towards the former Confederacy. In Watch for Me on the Mountain (1978), a bloody tale of desert survival and guerilla tactics, Apache leader Geronimo seeks revenge after his family is massacred by soldiers. Like Wales, Geronimo is driven to kill by outside forces.

Carter achieved his greatest fame with a very different kind of book. His novel The Education of Little Tree (1976) is a coming-of-age tale filled with criticisms of institutionalized religion and politics. Its protagonist, Little Tree, a young orphaned Cherokee boy, experiences the bigotry and deceit of church officials and politicians. Carter falsely claimed the account was autobiographical. It was reviewed widely and praised greatly.

In 1976, Carter drew media scrutiny after the film, The Outlaw Josey Wales, was released, and a few journalists made the connection between Forrest Carter and Asa Carter, most notably Alabama author and journalist Wayne Greenhaw in an editorial in The New York Times in August of that year. Carter’s brother, Doug, maintained that they had never been Klan members and had belonged only to groups promoting segregation and states’ rights. Carter, however, continued to promote the hoax that he was Forrest Carter and in no way connected with Asa Carter, a story unknowingly promoted by his agent and many members of the news media. Carter’s fabricated persona was exposed even further when he appeared in an interview with Barbara Walters on the Today Show in 1976 and was recognized by former friends and associates in Alabama. He continued to maintain the pretense of being Forrest Carter and in some interviews came to refer to Asa Carter as his “no good” brother.

In June 1979, he was traveling from Texas to Los Angeles to discuss the possibility of a film version of Watch for Me on the Mountain. Several publications reported that he had been drinking when he stopped by his son’s home near Abilene on the night of June 7; he started a fight and fell, hitting his head on a counter. Emergency medical staff who arrived on the scene found him dead, apparently having choked to death on his own vomit. His body was returned to Alabama for burial in the cemetery of the DeArmanville Methodist Church, east of Oxford.

Works by Asa Carter (Forrest Carter)

Gone to Texas (1975)

The Education of Little Tree (1976)

The Vengeance Trail of Josey Wales (1978)

Watch for Me on the Mountain (1978)

Additional Resources

Barra, Allen. “The Education of Little Fraud.” Salon, December 20, 2001, http://archive.salon.com/books/feature/2001/12/20/carter/

Clayton, Lawrence. “Afterword”. In Josey Wales: Two Westerns by Forrest Carter. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989.

Gates, Henry Louis. ” ‘Authenticity,’ or The Lesson of Little Tree.” New York Times, Sunday Book Review, November 24, 1991.

Rubin, Dana. “The Real Education of Little Tree.” Texas Monthly 20 (February 1992): 79-81, 92-96.