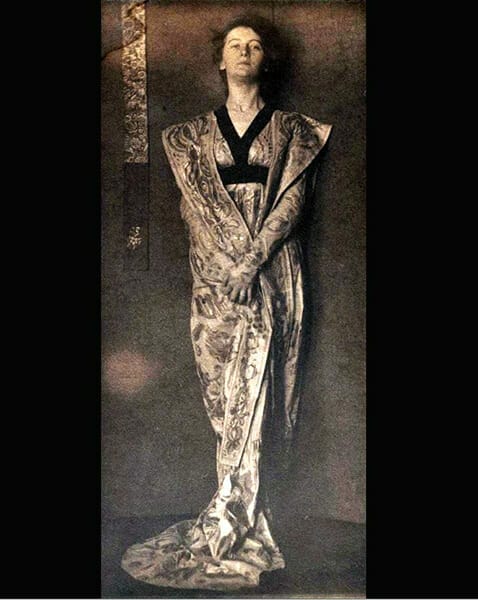

Mary McNeil Fenollosa

Mary McNeil Fenollosa

Mary McNeil Fenollosa (1865-1954), publishing primarily under the pseudonym Sidney McCall, was a popular novelist and poet in the early decades of the twentieth century. She grew up in Mobile and at different times in her life lived and wrote there. Several of her novels are set in Alabama. Today, she is remembered, if at all, as the wife of Ernest Fenollosa, a scholar of Asian culture and an art collector. But her well-constructed fiction deserves attention because it stands out from the mostly sentimental, plot-driven work of her contemporaries at the beginning of the twentieth century and because she creates believable and complex characters and places them in settings that effectively evoke the atmosphere of their time and place.

Mary McNeil Fenollosa

Mary McNeil Fenollosa (1865-1954), publishing primarily under the pseudonym Sidney McCall, was a popular novelist and poet in the early decades of the twentieth century. She grew up in Mobile and at different times in her life lived and wrote there. Several of her novels are set in Alabama. Today, she is remembered, if at all, as the wife of Ernest Fenollosa, a scholar of Asian culture and an art collector. But her well-constructed fiction deserves attention because it stands out from the mostly sentimental, plot-driven work of her contemporaries at the beginning of the twentieth century and because she creates believable and complex characters and places them in settings that effectively evoke the atmosphere of their time and place.

Mary McNeill (she later dropped an “l” from her name) was born on March 8, 1865, in Wilcox County on her grandparents’ plantation, the oldest of five children. Her father, William Stoddard McNeill of Mobile, was a lieutenant in the Confederate Army, and her mother, Laura Sibley, fled Baldwin County to her parents’ home after federal troops burned the family’s home. The family reunited after the war, and Mary grew up in Mobile and was educated at the city’s Irving Female Institute.

With her family in difficult financial circumstances, she married Ludolph Chester at 18, and the couple had a son, Allen Chester. Ludolph died two years into the marriage. Upon hearing of her loss, former suitor Ledyard Scott wrote to her from Tokyo with a proposal of marriage. Mary accepted and sailed for Japan in 1890 with her infant son, marrying Scott shortly after her arrival in Tokyo. The marriage was not a happy one, however, and Mary divorced Scott and returned to Mobile in 1892, now with two children, after the birth of her daughter, Erwin Scott. Despite the difficult circumstances, Mary developed a love of Japanese culture and art and continued to pursue her interest in it upon her return.

In 1895, Mary, now 30 years old, heard about and applied for a job in the Asian art division of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and began working with Ernest Fenollosa, the most prominent scholar of Asian art of the time. Ernest soon divorced his wife to marry Mary, causing such scandal in Boston society that the newly married couple decided to move to New York. They then moved to Japan in 1897, after Ernest was appointed the official arts commissioner to the Japanese emperor.

In Japan, the Fenollosas became the center of a group that included Japanese artists and scholars as well as fellow expatriates such as author Lafcadio Hearn and visiting Americans such as renowned historian Henry Adams and artist John LaFarge. Ernest researched Chinese and Japanese art, acted as a purchaser for the Boston Museum’s Asian collection, and advised fellow collectors (including Charles Freer, whose collection would eventually become the Freer Gallery of Art of the Smithsonian Institution), and Mary began writing poetry and fiction.

In 1899, Mary published her first collection of poems, Out of the Nest: A Flight of Verses. Reviewers praised her imagery, especially that contrasting East and West. In 1901, she published her first novel, Truth Dexter, under the pseudonym Sidney McCall. The novel tells the story of a southern wife, the title character, whose marriage is threatened by a lustful Boston socialite. Fenollosa decided not to use her real name because, having written the novel as a cure for homesickness and without thought of publishing it, she was afraid that the negative views of Boston society and the “big-city” wiles of the antagonist would reflect badly on her. Truth Dexter was an immediate and major success, selling extremely well and receiving positive reviews in both popular and critical magazines. Also in 1901, she published a long essay accompanied by color plates entitled Hiroshige, the Artist of Mist, Snow and Rain, under her own name.

The Dragon Painter Cover

Her second and third novels, The Breath of the Gods (1905) and The Dragon Painter (1906), were both set in Japan. Breath of the Gods, published under Sidney McCall, centered on an American senator appointed ambassador to Japan, his wife and daughter, and the daughter’s Japanese fellow student, whose story of returning to Japan is the center of the novel. It was a huge success and was adapted as a Broadway play, a film, and an opera. The Dragon Painter, the only novel published under her real name, tells the story of an aging Japanese artist who fears the introduction of Western traditions to his homeland and wants to pass his traditional approach to art on to an artist of the younger generation. The novel also was adapted as a film.

The Dragon Painter Cover

Her second and third novels, The Breath of the Gods (1905) and The Dragon Painter (1906), were both set in Japan. Breath of the Gods, published under Sidney McCall, centered on an American senator appointed ambassador to Japan, his wife and daughter, and the daughter’s Japanese fellow student, whose story of returning to Japan is the center of the novel. It was a huge success and was adapted as a Broadway play, a film, and an opera. The Dragon Painter, the only novel published under her real name, tells the story of an aging Japanese artist who fears the introduction of Western traditions to his homeland and wants to pass his traditional approach to art on to an artist of the younger generation. The novel also was adapted as a film.

Fenollosa published six more novels as Sidney McCall, as well as a book of children’s verses, Blossoms from a Japanese Garden (1913), under her own name, but she never repeated the success of her first three novels. The later novels are notable for their departure from Japanese subjects. Red Horse Hill (1909), an attack on child labor in the textile mills of Alabama, is interesting despite a melodramatic plot too dependent on coincidence; it was filmed in 1917 as The Eternal Mother, with Ethel Barrymore in the lead role. The Strange Woman (1914) is a novelization of a play of the same name by William J. Hurlbut. The Stirrup Latch (1915), a love story set in Mobile and Spring Hill, avoids the overly romantic and sentimental tone and plot that characterized many novels of the time and ranks in artistry with her first three novels, but it did not share their success. Ariadne of Allan Water (1914), Sunshine Beggars (1918), and Christopher Laird (1919) also met with little success.

Mary also contributed to her husband’s major work, Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design; she completed it after his untimely death in 1908, returning to Japan to check on dates and other factual details. Epochs was published in 1912 and was immediately recognized as the authoritative study on its subject. Fenollosa stopped writing after the publication of Christopher Laird. In 1952, she returned to southern Alabama, settling in Baldwin County, where her mother’s family, the Sibleys, had lived. She died on January 11, 1954, in Montrose, Baldwin County.

Works by Mary McNeil Fenollosa

Out of the Nest: A Flight of Verses (1899)

Truth Dexter (1901)

Hiroshige, the Artist of Mist, Snow and Rain: An Essay (1901)

The Breath of the Gods (1905)

The Dragon Painter (1906)

Red Horse Hill (1909)

“Foreword” to Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design (1912)

Blossoms from a Japanese Garden: A Book of Child-Verses (1913)

The Strange Woman (1914)

Ariadne of Allan Water (1914)

The Stirrup Latch (1915)

Sunshine Beggars (1918)

Additional Resources

Brooks, Van Wyck. Fenollosa and His Circle and Other Essays in Biography. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1962.

Chisolm, Lawrence W. Fenollosa: The Far East and American Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963.

Delaney, Caldwell. “Mary McNeil Fenollosa, An Alabama Woman of Letters.” Alabama Review 16 (July 1965): 163-73.

Dyer, Anne H. “Mary McNeil Fenollosa.” In Library of Southern Literature, edited by Edwin Anderson Alderman et al., vol. IV, pp. 1591-94 (New Orleans: Martin and Hoyt, 1913).

Rittenhouse, Jessie B. “Mary McNeil Fenollosa.” In The Younger American Poets. Boston: Little, Brown, 1904.