James G. "Jim" Clark Jr.

James G. “Jim” Clark Jr. (1922-2007) was the sheriff of Dallas County from 1955 to 1966. He, along with other Alabama officials, was responsible for much of the violence directed at civil rights protestors taking part in the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, including “Bloody Sunday.” He was defeated in 1966 in his bid for reelection, taking odd jobs and spending a brief time in prison before his death in 2007.

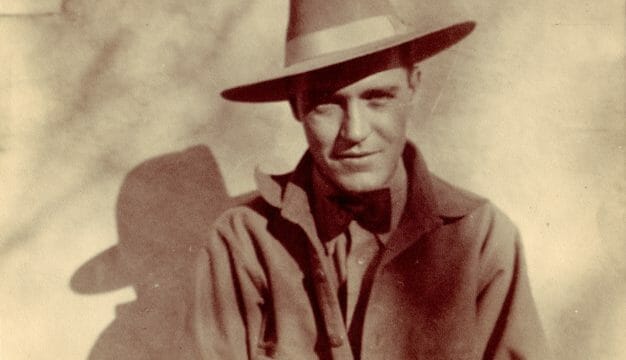

Jim Clark

Clark was born September 17, 1922, in Elba, Coffee County, to James Gardner and Ettie Lee Clark, one of two children; he graduated from Elba High School. He enrolled at the University of Alabama but interrupted his studies during World War II to serve in the Army Air Force as an engineer and gunner aboard bombers in the Aleutian Islands, returning to college in 1945. Clark moved to Dallas County after the war to raise cattle. Gov. James Folsom Sr., a childhood friend, appointed Clark sheriff in 1955 after the death of the previous officeholder. Clark won reelection twice at a time when only about one percent of Selma‘s eligible African Americans was registered to vote.

Jim Clark

Clark was born September 17, 1922, in Elba, Coffee County, to James Gardner and Ettie Lee Clark, one of two children; he graduated from Elba High School. He enrolled at the University of Alabama but interrupted his studies during World War II to serve in the Army Air Force as an engineer and gunner aboard bombers in the Aleutian Islands, returning to college in 1945. Clark moved to Dallas County after the war to raise cattle. Gov. James Folsom Sr., a childhood friend, appointed Clark sheriff in 1955 after the death of the previous officeholder. Clark won reelection twice at a time when only about one percent of Selma‘s eligible African Americans was registered to vote.

As the civil rights movement picked up momentum in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Clark became notorious for his use of violent tactics and intimidation of African Americans. He started a fight with Annie Lee Cooper, a 54-year-old black woman standing in line to register to vote, that ended with Clark’s deputies holding her down while he beat her with a billy club. Clark and his deputies used cattle prods on black youths at a civil rights demonstration to force them to march until some collapsed or vomited from exhaustion. Claiming that any attempt to gain voting rights by African Americans was part of a plan for “black supremacy,” Clark wore a small button reading “Never” as a symbol of his opposition to black civil rights.

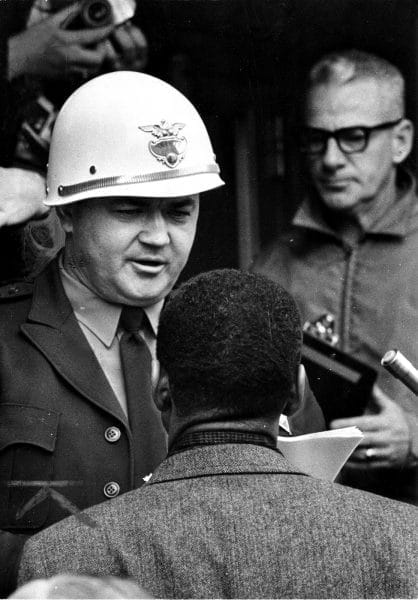

Sheriff Clark and Demonstrators

Clark was most famous for events during the first of the three Selma to Montgomery marches in March 1965. After the shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson during a nighttime demonstration in Marion, Perry County, on February 18, 1965, civil rights leaders from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) planned a march to bring attention to the violence and violations of their rights. On March 7, 1965, the approximately 600 marchers made it only six blocks before meeting state troopers and the Dallas County “sheriff’s posse,” led by Clark. On the east side of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the law officers ordered the protestors to disperse and then advanced, making no attempts at arrests as they violently assaulted the marchers in 30 minutes of carnage that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The troopers attacked first with billy clubs, then tear gas. Clark’s posse rode on horseback through the confusion, giving rebel yells and attacking protestors with bullwhips, ropes, and pieces of rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. Fifty-six marchers were hospitalized.

Sheriff Clark and Demonstrators

Clark was most famous for events during the first of the three Selma to Montgomery marches in March 1965. After the shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson during a nighttime demonstration in Marion, Perry County, on February 18, 1965, civil rights leaders from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) planned a march to bring attention to the violence and violations of their rights. On March 7, 1965, the approximately 600 marchers made it only six blocks before meeting state troopers and the Dallas County “sheriff’s posse,” led by Clark. On the east side of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the law officers ordered the protestors to disperse and then advanced, making no attempts at arrests as they violently assaulted the marchers in 30 minutes of carnage that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The troopers attacked first with billy clubs, then tear gas. Clark’s posse rode on horseback through the confusion, giving rebel yells and attacking protestors with bullwhips, ropes, and pieces of rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. Fifty-six marchers were hospitalized.

Reporters captured almost the entire attack on tape. That night, the American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) interrupted its regular programming to run footage of the brutality in Selma. Whereas the country had seen brutal violence in Birmingham in 1963 and during the Freedom Rides in 1961, the massive scale of the state-sanctioned violence in Selma shocked the nation. Numerous congressmen demanded federal action. Even Gov. George Wallace, recognizing the threat that the footage posed to the segregationist cause, felt compelled to reprimand Clark and the troopers. The violence of Bloody Sunday encouraged the passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965. That same year, repeated death threats against him forced Clark to move with his wife and their five children to the Selma jail for safety.

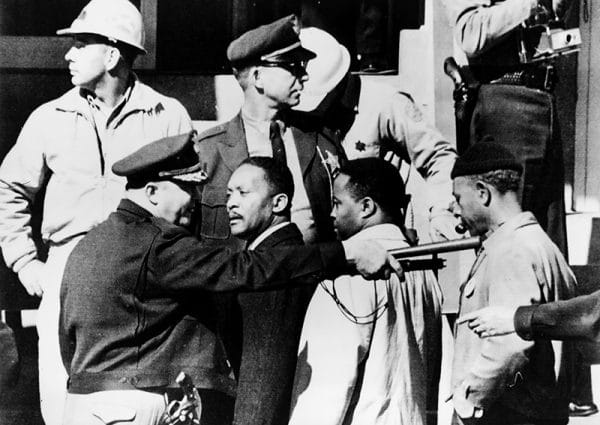

Wilson Baker and Jim Clark

In part because of the increased number of black voters in Dallas County, which was majority African American, Clark was defeated in the election of 1966. He took a variety of jobs, including selling mobile homes, and faced some financial hardship after losing office. In 1978, a federal grand jury in Montgomery indicted Clark on charges of conspiring to smuggle three tons of marijuana from Colombia. Clark was sentenced to two years in prison and ended up serving nine months. He died in a nursing home in Elba on June 4, 2007, as the result of a stroke and complications of a heart condition.

Wilson Baker and Jim Clark

In part because of the increased number of black voters in Dallas County, which was majority African American, Clark was defeated in the election of 1966. He took a variety of jobs, including selling mobile homes, and faced some financial hardship after losing office. In 1978, a federal grand jury in Montgomery indicted Clark on charges of conspiring to smuggle three tons of marijuana from Colombia. Clark was sentenced to two years in prison and ended up serving nine months. He died in a nursing home in Elba on June 4, 2007, as the result of a stroke and complications of a heart condition.

Along with men like Eugene “Bull” Connor, Clark became a symbol of the total refusal of some white Alabamians to accept any sort of black civil or political rights. He remained defiant until his death, insisting that outside agitators caused the unrest of the 1960s. Clark asserted that events of Bloody Sunday had been blown out of proportion and blamed the demonstrators for the initial violence of the day. In 2006, Clark said that given the same situation, he would repeat his actions from March 1965.

Additional Resources

Bernstein, Adam. “Ala. Sheriff James Clark, Embodied Violent Bigotry.” New York Times, June 7, 2007.

Fager, Charles E. Selma, 1965. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974.

Fox, Margalit. “Jim Clark, Sheriff Who Enforced Segregation, Dies at 84.” Washington Post, June 7, 2007.

Gaillard, Frye. Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement that Changed America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.