Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Alabama Air National Guard

In 1961, members of the Alabama Air National Guard (ANG) secretly took part in the failed invasion of Cuba known as the Bay of Pigs, a covert attempt by the United States to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro. Approximately 60 members of the Alabama Guard were involved, including four pilots and four enlisted crewmembers who flew four bombers (two per bomber) to support the invasion by U.S.-backed Cuban exiles. These eight Alabama guardsmen flew combat missions on the last day when the Cuban pilots were exhausted. It was a desperate measure, but the Cubans on the beaches needed help badly. The mission proved fatal to four members of the Alabama unit. U.S. president John F. Kennedy later acknowledged America’s involvement but denied that American military personnel had entered Cuban territory. Not until 1987 did the U.S. reveal that eight ANG members had indeed flown into Cuban airspace.

Douglas B-26C Invader

What became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion came in the midst of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. U.S. officials had become alarmed at the increasingly close relationship between the Soviet leaders and Castro, who had led a communist overthrow of the Cuban government in 1959. In 1960, Alabama Gov. John Patterson had approved a request by Brig. Gen. Reid Doster, commander of the Alabama ANG’s 117th Reconnaissance Wing, to recruit personnel to assist the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Their mission was to train and advise Cuban exiles to fly, arm, and maintain 16 Douglas B-26 Invaders painted to resemble those used in the Cuban Air Force, not to fly combat missions themselves. The Cuban-exile pilots had varied flying backgrounds, but most had not flown the B-26. According to the plan, the planes were to disable Castro’s planes in bombing raids on April 15 and 16, 1961. The landing force, ammunition, and fuel would arrive in the bay aboard five merchant vessels before dawn on April 17. The resistance troops would then take the beachhead and the airstrip. Invasion planners had all 16 of the B-26s painted in the colors and insignia (and actual numbers) of the Cuban air force B-26s, hoping that the Cuban population would believe that Castro’s own pilots were in revolt against him and become inspired to join the invasion force in a mass uprising. The Alabama ANG had been chosen to train the exiles because they were the last American military unit to fly and maintain the by-then obsolete B-26 bomber.

Douglas B-26C Invader

What became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion came in the midst of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. U.S. officials had become alarmed at the increasingly close relationship between the Soviet leaders and Castro, who had led a communist overthrow of the Cuban government in 1959. In 1960, Alabama Gov. John Patterson had approved a request by Brig. Gen. Reid Doster, commander of the Alabama ANG’s 117th Reconnaissance Wing, to recruit personnel to assist the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Their mission was to train and advise Cuban exiles to fly, arm, and maintain 16 Douglas B-26 Invaders painted to resemble those used in the Cuban Air Force, not to fly combat missions themselves. The Cuban-exile pilots had varied flying backgrounds, but most had not flown the B-26. According to the plan, the planes were to disable Castro’s planes in bombing raids on April 15 and 16, 1961. The landing force, ammunition, and fuel would arrive in the bay aboard five merchant vessels before dawn on April 17. The resistance troops would then take the beachhead and the airstrip. Invasion planners had all 16 of the B-26s painted in the colors and insignia (and actual numbers) of the Cuban air force B-26s, hoping that the Cuban population would believe that Castro’s own pilots were in revolt against him and become inspired to join the invasion force in a mass uprising. The Alabama ANG had been chosen to train the exiles because they were the last American military unit to fly and maintain the by-then obsolete B-26 bomber.

Most of the approximately 60 Air Guardsmen who participated in the Bay of Pigs grew up within 15 miles of the Birmingham Airport. Seven or more had attended Tarrant High School, near the Birmingham ANG headquarters. Many of the Alabama participants had similar backgrounds and several had served together in the U.S. Air Force and the Alabama ANG or were coworkers at Hayes Aircraft. The guardsmen volunteered in 1961 under terms of absolute secrecy and deployed in small groups to a training base in Guatemala and later to a secret CIA installation at Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, the staging base for the operation.

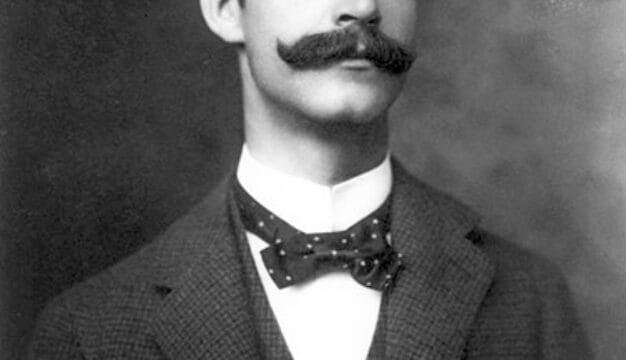

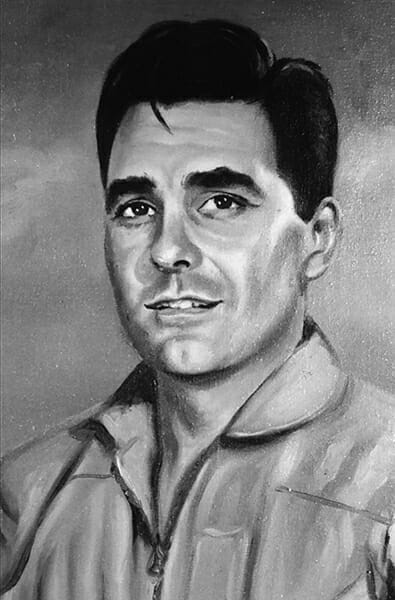

Riley Shamburger

Under President Kennedy’s orders, only eight of the total force of sixteen B-26s (with a pilot and crewmember in each) flew to Cuba on April 15. As a result, only half of Castro’s planes were disabled, leaving the other half to lay in wait for the invasion force on April 17. Castro’s remaining air force destroyed two of five U.S. merchant vessels waiting to supply the troops, and the three remaining ships quickly departed with extra troops, ammunition, and fuel. The resistance fighters secured the beachhead and the airstrip but soon found themselves trapped. The Cuban exiles in the air provided as much support to their ground forces as they could, but with little effect. The Cuban expatriate air force lost five of its sixteen B-26s and crews that day. The remaining crews and aircraft limped back to Puerto Cabezas. The expatriates worked with the Alabama guardsmen to repair the damaged planes and then flew back to Cuba, a six-hour mission over open water. Crews went without sleep until exhaustion set in and they became unable to fly. The next day, CIA officials in Washington told the president that U.S. planes and crews from the naval force conducting exercises nearby (on standby if ordered) must support the invasion.

Riley Shamburger

Under President Kennedy’s orders, only eight of the total force of sixteen B-26s (with a pilot and crewmember in each) flew to Cuba on April 15. As a result, only half of Castro’s planes were disabled, leaving the other half to lay in wait for the invasion force on April 17. Castro’s remaining air force destroyed two of five U.S. merchant vessels waiting to supply the troops, and the three remaining ships quickly departed with extra troops, ammunition, and fuel. The resistance fighters secured the beachhead and the airstrip but soon found themselves trapped. The Cuban exiles in the air provided as much support to their ground forces as they could, but with little effect. The Cuban expatriate air force lost five of its sixteen B-26s and crews that day. The remaining crews and aircraft limped back to Puerto Cabezas. The expatriates worked with the Alabama guardsmen to repair the damaged planes and then flew back to Cuba, a six-hour mission over open water. Crews went without sleep until exhaustion set in and they became unable to fly. The next day, CIA officials in Washington told the president that U.S. planes and crews from the naval force conducting exercises nearby (on standby if ordered) must support the invasion.

The CIA finally authorized the Alabama guardsmen to fly on April 19. The men were warned that should they be captured, the United States would declare that the men were mercenaries and disavow any knowledge of their activities. Despite the grim prospect, eight Alabama guardsmen—four pilots and four crewmen—stepped forward. The lead formation was commanded by Billy “Dodo” Goodwin, a major in the Alabama ANG, and Gonzalo Herrera, a Cuban pilot known as “El Tigre.” Alabama pilots Joe Shannon, Riley Shamburger, and Thomas Willard “Pete” Ray and Alabama crewmembers Leo F. Baker, Wade Gray, Nick Sedano, and James Vaughn also volunteered. A second exiled Cuban pilot, Mario Zuniga, and his crewmember joined the strike force of six B-26s. The records do not indicate whether Herrera had a crewmember with him; by this time volunteers were scarce, so he may have flown by himself.

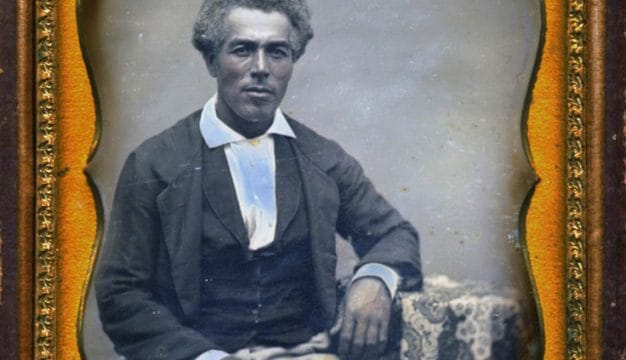

Leo Baker

Early on April 19, 1961, the six B-26 Invaders, painted in Cuban Air Force colors but manned by the eight Alabama and three (perhaps four) Cuban exiles, took off from Puerto Cabezas and headed toward Cuba. The guardsmen were promised air cover from the USS Essex, a U.S. aircraft carrier off the Cuban coast in international waters, but as the bombers arrived over the beachhead at sunrise, Castro’s fighter jets lay in wait for them. The two lead B-26s came under attack and the promised air support from the Essex did not materialize. Riley Shamburger and his crewmember Wade Gray were hit and crashed into the water with their plane, and their bodies were not recovered. Further inland, Cuban gunners brought down Pete Ray’s bomber. He and crewmember Leo F. Baker survived the crash, only to be killed in a shootout with Cuban soldiers. As the remaining B-26 crews flew out of the area, jet fighters from the Essex finally appeared. In a tragic mix-up, perhaps related to time zones, the jets had arrived one hour too late.

Leo Baker

Early on April 19, 1961, the six B-26 Invaders, painted in Cuban Air Force colors but manned by the eight Alabama and three (perhaps four) Cuban exiles, took off from Puerto Cabezas and headed toward Cuba. The guardsmen were promised air cover from the USS Essex, a U.S. aircraft carrier off the Cuban coast in international waters, but as the bombers arrived over the beachhead at sunrise, Castro’s fighter jets lay in wait for them. The two lead B-26s came under attack and the promised air support from the Essex did not materialize. Riley Shamburger and his crewmember Wade Gray were hit and crashed into the water with their plane, and their bodies were not recovered. Further inland, Cuban gunners brought down Pete Ray’s bomber. He and crewmember Leo F. Baker survived the crash, only to be killed in a shootout with Cuban soldiers. As the remaining B-26 crews flew out of the area, jet fighters from the Essex finally appeared. In a tragic mix-up, perhaps related to time zones, the jets had arrived one hour too late.

The invasion collapsed that afternoon, and the resistance fighters, having exhausted their supplies and ammunition, surrendered to Castro’s army. It had taken Castro’s forces just 72 hours to defeat the invasion. Castro held the prisoners until December 1963, when he ransomed them to the United States for food and medicine worth $53 million. Pete Ray’s body was placed in a morgue, where it remained for 17 years as evidence that the U.S. military had invaded Cuba. Leo Baker was dark-skinned, appeared to be Cuban, and was buried with the other dead Cuban invaders. After it was over, the surviving Alabamians were quickly and quietly brought back to Birmingham and told to forget the whole affair. Despite the controversy surrounding the Bay of Pigs fiasco and their feelings of betrayal, the Alabama guardsmen kept their silence for decades. Four of the Alabama guardsmen who had helped train and advise the Cuban exiles—Ulay Littleton, Dalton Livingston, Charles Weldon, and Carl Sudano—continued to work with the CIA after the invasion.

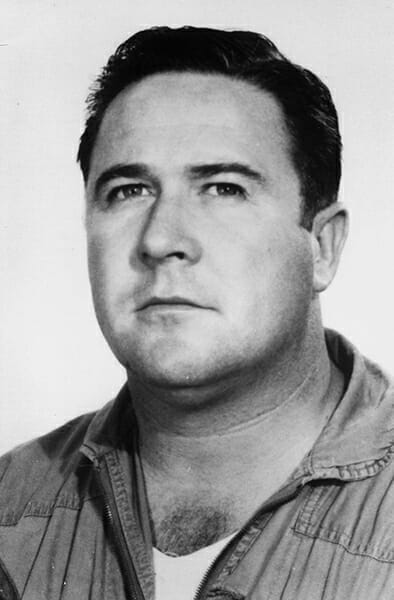

Thomas “Pete” Ray

In 1978, the CIA declassified critical documents and posthumously awarded Shamburger, Gray, Ray, and Baker the Distinguished Intelligence Cross—the agency’s highest award for bravery. After years of persistent prodding by Pete Ray’s daughter, Janet Weininger, the U.S. government convinced Castro to return Ray’s body in 1979 for a military burial at Forest Hills Cemetery overlooking the Birmingham airport. In May 1997, the CIA honored 70 agency personnel who gave their lives in the service of their country, including the four Alabama guardsmen. In a special ceremony at the Alabama ANG facility in Birmingham on January 2001, CIA officials presented Agency Seal Medallions to Joe Shannon, Carl Sudano, the families of deceased Air Guard pilots Billy Goodwin and Dalton Livingston, and the family of deceased crewmember James Vaughn. The role of the 60 Alabama Air National Guard members in the doomed effort to overthrow Castro is now a matter of public record.

Thomas “Pete” Ray

In 1978, the CIA declassified critical documents and posthumously awarded Shamburger, Gray, Ray, and Baker the Distinguished Intelligence Cross—the agency’s highest award for bravery. After years of persistent prodding by Pete Ray’s daughter, Janet Weininger, the U.S. government convinced Castro to return Ray’s body in 1979 for a military burial at Forest Hills Cemetery overlooking the Birmingham airport. In May 1997, the CIA honored 70 agency personnel who gave their lives in the service of their country, including the four Alabama guardsmen. In a special ceremony at the Alabama ANG facility in Birmingham on January 2001, CIA officials presented Agency Seal Medallions to Joe Shannon, Carl Sudano, the families of deceased Air Guard pilots Billy Goodwin and Dalton Livingston, and the family of deceased crewmember James Vaughn. The role of the 60 Alabama Air National Guard members in the doomed effort to overthrow Castro is now a matter of public record.

Additional Resources

Ferrer, Edward B. Operation Puma. Miami: Open Road Press, 1975.

Meyer, Karl E., and Tad Szulc. The Cuban Invasion. New York: Praeger, 1962.

Person, Buck. Bay of Pigs. Jefferson, Missouri: McFarland & Co., 1990.

Trest, Warren, and Don Dodd. Wings of Denial: The Alabama Air National Guard’s Covert Role at the Bay of Pigs. Montgomery: New South Books, 2001.

Wyden, Peter. Bay of Pigs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979.