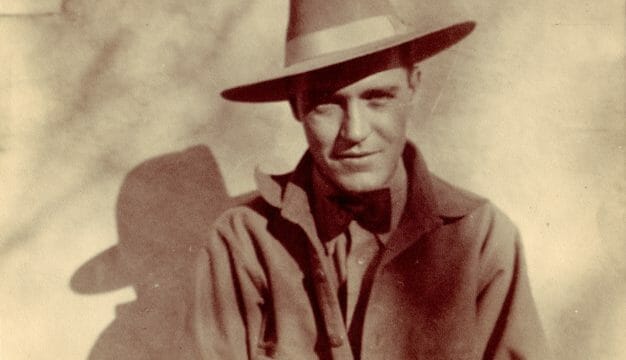

James Reeb

A social worker and Unitarian Universalist minister, James Reeb (1927-1965) was severely beaten by a group of white men in Selma on March 9, 1965. Reeb died of head trauma two days later in a Birmingham hospital. His death shocked the nation and was referred to in a press conference by Pres. Lyndon Johnson, who then asked Congress in a national address to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

James Reeb

James Joseph Reeb was born on January 1, 1927, to Harry and Mae Reeb in Wichita, Kansas. The family was poor and moved often while his father searched for work, eventually settling in Wyoming. As a teenager, he was considered a bright student and an excellent debater, although somewhat of an outcast because of his crossed eyes (which were later surgically corrected). A deeply committed Christian, Reeb unsurprisingly settled on the ministry as a career. After serving in the Army during World War II, he attended St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, on the GI Bill and met Marie Deason, who he married on August 20, 1950. The couple would have four children.

James Reeb

James Joseph Reeb was born on January 1, 1927, to Harry and Mae Reeb in Wichita, Kansas. The family was poor and moved often while his father searched for work, eventually settling in Wyoming. As a teenager, he was considered a bright student and an excellent debater, although somewhat of an outcast because of his crossed eyes (which were later surgically corrected). A deeply committed Christian, Reeb unsurprisingly settled on the ministry as a career. After serving in the Army during World War II, he attended St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, on the GI Bill and met Marie Deason, who he married on August 20, 1950. The couple would have four children.

Reeb entered Princeton Theological Seminary in Princeton, New Jersey, and also served as chaplain at Philadelphia General Hospital in nearby Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After graduating in 1953, he continued working at the hospital and also volunteered with inner-city youth through the Philadelphia YMCA. He was granted fellowship as a Unitarian Universalist minister in 1959 and moved to Washington, D.C. to become assistant minister at All Souls Church, located in a poor black neighborhood. There, Reeb organized the University Neighborhood Council to address the growing social needs of the neighborhood surrounding the church and soon dedicated the majority of his time to social issues. Leaving the pulpit to pursue social ministry, Reeb moved to Boston to work for the Quaker-run American Friends Service Committee, settling with his wife and four children in an economically depressed black neighborhood in Dorchester against the advice of his contemporaries. He took up the cause of low-income housing, launching a public campaign for new safety and building codes in early 1965.

Bloody Sunday

Reeb was drawn to the civil rights activities in Alabama in response to the violence that occurred on Sunday, March 7, 1965, when local and state law enforcement officials responded with brute force against marchers attempting to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge en route to Montgomery in a peaceful demonstration for equal voting rights. After that incident, which garnered worldwide attention and quickly became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Martin Luther King Jr. issued a nationwide call to the clergy, urging representatives of all denominations and faiths to journey to Alabama and stand with African Americans there for the cause of voting rights. Joining fellow Unitarian ministers Clark Olsen and Orloff Miller, Reeb was part of a large delegation from the Boston-based Unitarian Universalist Association that travelled to Alabama. Reeb, whose wife and four children remained at home in Boston, planned to make only a long day trip to Alabama. Traveling by plane through Atlanta to Montgomery, he joined a reported 450 fellow clergy from around the nation in Selma at mid-day on Tuesday, March 9, 1965.

Bloody Sunday

Reeb was drawn to the civil rights activities in Alabama in response to the violence that occurred on Sunday, March 7, 1965, when local and state law enforcement officials responded with brute force against marchers attempting to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge en route to Montgomery in a peaceful demonstration for equal voting rights. After that incident, which garnered worldwide attention and quickly became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Martin Luther King Jr. issued a nationwide call to the clergy, urging representatives of all denominations and faiths to journey to Alabama and stand with African Americans there for the cause of voting rights. Joining fellow Unitarian ministers Clark Olsen and Orloff Miller, Reeb was part of a large delegation from the Boston-based Unitarian Universalist Association that travelled to Alabama. Reeb, whose wife and four children remained at home in Boston, planned to make only a long day trip to Alabama. Traveling by plane through Atlanta to Montgomery, he joined a reported 450 fellow clergy from around the nation in Selma at mid-day on Tuesday, March 9, 1965.

The out-of-town clergy who had answered King’s call, together with hundreds of local African American citizens, demonstrated that afternoon at the site of the Bloody Sunday attack. After prayer in the evening, activities ceased until the following day. Reeb, Olsen, and Miller then headed to a Selma cafe for dinner. Leaving on foot after their meal, the three inadvertently walked onto a side street in the all-white part of town. Passing by the Silver Moon Café, an all-white establishment, and easily identifiable as outsiders associated with the voting rights march, the three ministers were attacked by men with clubs, one of which cracked James Reeb’s skull.

Requiring medical attention and likely to be denied treatment by physicians at Selma’s all-white hospital, Reeb was taken to Burwell Infirmary, the town’s medical facility for African Americans. The head of the infirmary, D. W. Dinkins, immediately determined that treatment from a team of neurologists was necessary to deal with Reeb’s injuries, care that could be obtained closest in Birmingham, 100 miles away.

As physicians in Birmingham were alerted about Reeb’s condition, an ambulance from a black funeral home transported Reeb, Miller, Clark, Dinkins, and an attendant to the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) hospital. However, en route to Birmingham, the mixed-race group had to deal with a flat tire and delayed aid from law enforcement, which had pledged assistance in getting the victim to Birmingham as quickly as possible. By the time Reeb arrived at UAB, word of his life-threatening injuries at the hands of white supremacists in Alabama had made headlines across the country.

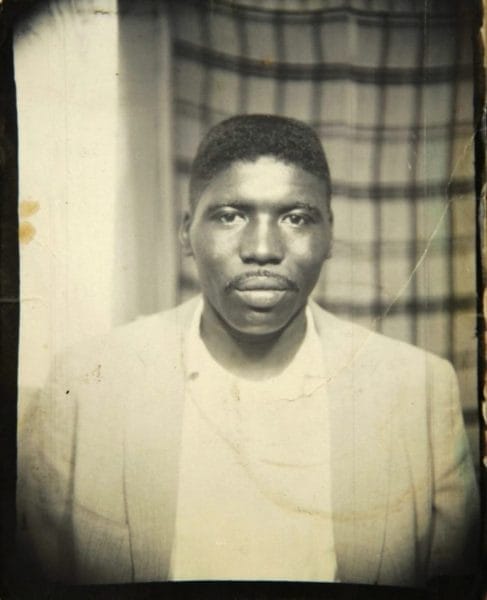

Jimmie Lee Jackson

Unlike the shooting death of African American activist Jimmie Lee Jackson just three weeks earlier, Reeb’s injuries brought an unprecedented level of attention to the civil rights movement in Selma. Hundreds of Reeb’s well-wishers gathered outside of Boston’s federal building to stage a Wednesday protest against Selma law enforcement. President Johnson phoned Reeb’s wife, Marie, to offer both his support and an airplane to fly her to Birmingham; he also supplied a plane to fly Reeb’s father to Birmingham from Casper, Wyoming.

Jimmie Lee Jackson

Unlike the shooting death of African American activist Jimmie Lee Jackson just three weeks earlier, Reeb’s injuries brought an unprecedented level of attention to the civil rights movement in Selma. Hundreds of Reeb’s well-wishers gathered outside of Boston’s federal building to stage a Wednesday protest against Selma law enforcement. President Johnson phoned Reeb’s wife, Marie, to offer both his support and an airplane to fly her to Birmingham; he also supplied a plane to fly Reeb’s father to Birmingham from Casper, Wyoming.

Reeb lingered on life support for a day and a half after surgery at UAB. Reporters from throughout the nation kept vigil outside the hospital, and Marie Reeb was interviewed by television reporters on Wednesday evening, March 10. She explained to them that because he believed in the aims of the civil rights movement, almost nothing could have stopped her husband from going to Selma, though he knew the risks associated with doing so. On the morning after that interview, Reeb was taken off life support and passed away. He was 38 years old.

Upon learning of Reeb’s death, groups nationwide staged demonstrations in support of the civil rights movement and in memory of the young minister considered to have given his life to the cause. A formal memorial service was held at Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, at which King, flanked by ministers of all faiths, gave a rousing eulogy entitled, “A Witness to the Truth.” Elsewhere, an estimated 30,000 gathered for a service in his memory in Boston, and memorials and marches also were held in Washington, D.C.; Northfield, Minnesota; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Princeton University.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

President Johnson, like many other U.S. citizens, was deeply moved at the martyrdom of a white man in the cause of African American civil rights. Coupled with the events of Bloody Sunday, Reeb’s death galvanized the president and the U.S. Congress. President Johnson addressed Congress and the nation on March 15, urging passage of the Voting Rights Act and famously uttering the phrase, “We shall overcome.” Congress passed the legislation and Johnson signed it into law in August of that year.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

President Johnson, like many other U.S. citizens, was deeply moved at the martyrdom of a white man in the cause of African American civil rights. Coupled with the events of Bloody Sunday, Reeb’s death galvanized the president and the U.S. Congress. President Johnson addressed Congress and the nation on March 15, urging passage of the Voting Rights Act and famously uttering the phrase, “We shall overcome.” Congress passed the legislation and Johnson signed it into law in August of that year.

In the wake of the attack on James Reeb, four Selma men were arrested and charged with murder, but they were immediately released on bond. A few months after Reeb’s death, an all-white, all-male jury in Dallas County acquitted Elmer Cook, Stanley Hoggle, and O’Neal Hoggle of all charges; the fourth individual left Alabama for Mississippi and the judge declared he did not have to stand trial.

Reeb was cremated and his ashes scattered in Wyoming. The James Reeb Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Madison, Wisconsin, was named in his honor in 1993.

Additional Resources

Garrow, David. Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978.

Howlett, Duncan. No Greater Love: The James Reeb Story. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

Kent, Martin. Free at Last: Civil Rights Heroes. VHS video. Beverly Hills, Calif.: World Almanac Video, 1999.