Methodism in Alabama

From the early years of the nineteenth century, Alabama Methodists have founded numerous churches and educational institutions. The denomination splintered over the issue of race, first in the 1840s and then after the Civil War. But all Methodists continued into the twentieth century their strong support for social and individual reform.

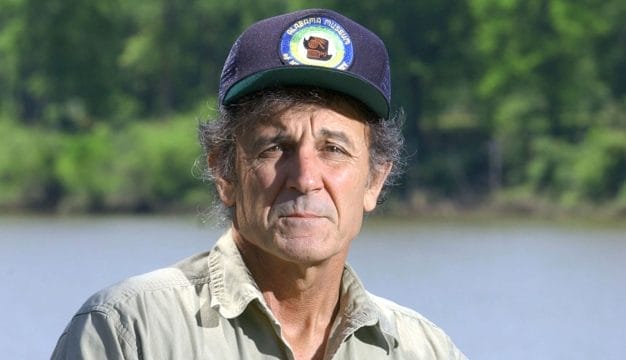

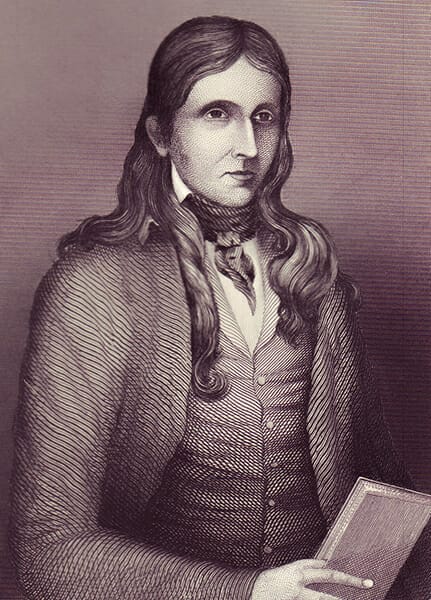

Lorenzo Dow

The entrance of Methodism into present-day Alabama is credited to the minister Lorenzo Dow, who in 1803 passed through the country north of Mobile and is believed to have delivered the first Protestant sermon to the frontiersmen there. Yet, the formal establishment of Methodism in Alabama came five years later in early 1808 when Matthew P. Sturdevant was sent by the South Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) to the same settlements along the Tombigbee River. Later that same year, James Gwinn was sent from the Western Conference, then meeting at Liberty Hill, Tennessee, to minister to settlers living in the Great Bend region of the Tennessee River, near present-day Huntsville.

Lorenzo Dow

The entrance of Methodism into present-day Alabama is credited to the minister Lorenzo Dow, who in 1803 passed through the country north of Mobile and is believed to have delivered the first Protestant sermon to the frontiersmen there. Yet, the formal establishment of Methodism in Alabama came five years later in early 1808 when Matthew P. Sturdevant was sent by the South Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) to the same settlements along the Tombigbee River. Later that same year, James Gwinn was sent from the Western Conference, then meeting at Liberty Hill, Tennessee, to minister to settlers living in the Great Bend region of the Tennessee River, near present-day Huntsville.

Young Methodist ministers such as Sturdevant and Gwinn rode the circuit (hence the term “circuit riders”). They wore heavy coats and wide-brimmed hats to fend off the elements, carried in their saddlebags a Bible and a hymnal, and preached in the most remote parts of the frontier. Much of their labor was devoted to camp meetings or revivals, often held outdoors, that attracted much attention throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. Ministers aimed to convert settlers, and to those not caught up in the enthusiasm, their behavior seemed bizarre. As some believers became overcome with fervor, they barked like dogs, engaged in a maniacal chuckling referred to as “the holy laugh,” or exhibited an uncontrollable twitching known as “the jerks.”

Alabama Conference Female College

Within a few decades, Alabama had lost its frontier edge and the Methodist circuit riders had toned down much of their emotional pitch. Churches were common in villages and towns. Methodism attracted people from all walks of life, including planters, merchants, farmers, and slaves. Throughout the nineteenth century, Methodists promoted many of the great reform issues, particularly education and temperance, an important topic in a time of alcoholic excess. The church’s English founder, Oxford-schooled John Wesley, had been among the most educated men of the early eighteenth century and placed a premium on individuals’ capacity for reforming their behavior, which in turn depended a great deal on disciplined study. Additionally, the continued success of Methodism in America depended a great deal on a trained clergy. Thus it was no surprise when in 1830 Methodists opened the doors to Alabama’s first institution of higher education, LaGrange College, which would form the nucleus of what is now the University of North Alabama in Florence. In addition, Methodists took over control of Athens Female Academy in 1842, which later became Athens State University. In 1854, Methodists established Tuskegee Female College, which later became Huntingdon College. Two years later, Southern University (now Birmingham-Southern College) was chartered in Greensboro. The church took over East Alabama Male College in 1859, now known as Auburn University.

Alabama Conference Female College

Within a few decades, Alabama had lost its frontier edge and the Methodist circuit riders had toned down much of their emotional pitch. Churches were common in villages and towns. Methodism attracted people from all walks of life, including planters, merchants, farmers, and slaves. Throughout the nineteenth century, Methodists promoted many of the great reform issues, particularly education and temperance, an important topic in a time of alcoholic excess. The church’s English founder, Oxford-schooled John Wesley, had been among the most educated men of the early eighteenth century and placed a premium on individuals’ capacity for reforming their behavior, which in turn depended a great deal on disciplined study. Additionally, the continued success of Methodism in America depended a great deal on a trained clergy. Thus it was no surprise when in 1830 Methodists opened the doors to Alabama’s first institution of higher education, LaGrange College, which would form the nucleus of what is now the University of North Alabama in Florence. In addition, Methodists took over control of Athens Female Academy in 1842, which later became Athens State University. In 1854, Methodists established Tuskegee Female College, which later became Huntingdon College. Two years later, Southern University (now Birmingham-Southern College) was chartered in Greensboro. The church took over East Alabama Male College in 1859, now known as Auburn University.

Government Street Methodist Church, ca. 1933

Yet the greatest reform issue of the day, slavery, divided Methodists. John Wesley had published tracts opposing the slave trade, and Methodists were strongly involved in the early antislavery movement in the United States. But Methodists in the South turned silent as slavery expanded throughout the early nineteenth century, whereas Northern Methodists would not be silenced. The General Conference of the MEC, which met in New York City in 1844, consumed 11 days debating slavery. In the end, the southerners split from the church the following year to create the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MEC, South). For the next two decades, no MEC congregations could be found in Alabama, but southern Methodists in Alabama could boast of more than 200,000 members and nearly 800 churches by the eve of the Civil War.

Government Street Methodist Church, ca. 1933

Yet the greatest reform issue of the day, slavery, divided Methodists. John Wesley had published tracts opposing the slave trade, and Methodists were strongly involved in the early antislavery movement in the United States. But Methodists in the South turned silent as slavery expanded throughout the early nineteenth century, whereas Northern Methodists would not be silenced. The General Conference of the MEC, which met in New York City in 1844, consumed 11 days debating slavery. In the end, the southerners split from the church the following year to create the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MEC, South). For the next two decades, no MEC congregations could be found in Alabama, but southern Methodists in Alabama could boast of more than 200,000 members and nearly 800 churches by the eve of the Civil War.

Sears Chapel, Coosa County

The war’s end saw significant changes among Alabama’s Methodists. Black Methodists, in particular, were anxious to leave the patronage of white churches, where they had been treated as little more than children. By 1866, only a third of black Methodists remained affiliated with the MEC, South in Alabama. They instead flocked to the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AME Zion), which had been formally established in Philadelphia in 1816 and New York in 1821. As early as 1864, two AME ministers preached in Mobile; but the formal organization began in 1867 through the efforts of missionaries sent from Georgia to establish the denomination in Alabama. In what may have been a typical process, a missionary sent by the AME preached to Brown Chapel in Selma on August 30, 1867. At the end of the service he asked if the congregation wanted to align itself with the AME. When no one objected, the church was considered a member of the AME.

Sears Chapel, Coosa County

The war’s end saw significant changes among Alabama’s Methodists. Black Methodists, in particular, were anxious to leave the patronage of white churches, where they had been treated as little more than children. By 1866, only a third of black Methodists remained affiliated with the MEC, South in Alabama. They instead flocked to the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AME Zion), which had been formally established in Philadelphia in 1816 and New York in 1821. As early as 1864, two AME ministers preached in Mobile; but the formal organization began in 1867 through the efforts of missionaries sent from Georgia to establish the denomination in Alabama. In what may have been a typical process, a missionary sent by the AME preached to Brown Chapel in Selma on August 30, 1867. At the end of the service he asked if the congregation wanted to align itself with the AME. When no one objected, the church was considered a member of the AME.

The original Methodist Episcopal Church looked upon the end of the war as the time to reunite Methodism. The war had ended political secession, and now it was time to end the religious division that had begun two decades before. Once again, missionaries were sent to Alabama, led by Arad Lakin of New York and Indiana. The MEC was formally reestablished in 1867 in Talladega, its membership largely confined to the Unionist strongholds in the hills of north Alabama where animosities lingered. The MEC was derisively labeled the “Northern Methodist Church” and Lakin was himself nearly lynched by the Ku Klux Klan. His attempts to establish a biracial MEC were stymied until 1876, when he helped establish a racially separate Central Alabama Conference within the MEC.

Highlands United Methodist Church

With black members leaving to join other Methodist branches, the leaders of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South decided in 1870 to ordain black ministers and to hand over churches and property to a new denomination named the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (the CME), whose name would change to the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1954.

Highlands United Methodist Church

With black members leaving to join other Methodist branches, the leaders of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South decided in 1870 to ordain black ministers and to hand over churches and property to a new denomination named the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (the CME), whose name would change to the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1954.

Whereas the Methodist Church stumbled with regard to race relations, it was a leader in the temperance movement, encouraging abstinence from alcohol. When in 1856, for example the citizens of Greensboro learned that the charter for Southern University also banned the sale of alcohol in the town, a banner was unfurled across Main Street reading “Sold Out to the Methodists,” expressing residents’ displeasure. This early example of local restriction set a pattern for others. Frustrated with the results of promoting individual temperance, Methodist women in particular began to support public prohibition during the 1880s. Statewide prohibition went into effect at the beginning of 1909, with strong Methodist backing.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Methodists were also caught up with other social problems associated with a modern industrial economy. Immigrants from southern and eastern Europe who landed in Birmingham and the mining towns of central Alabama were unprepared. They lived in crowded homes and spoke no English. In Ensley, Mobile, and elsewhere, Methodist women established settlement homes to minister to immigrants and others struggling to assimilate their old ways to a new order. This was called the Social Gospel, a program of Christian benevolence endorsed by the Methodists in 1907.

Maplesville United Methodist Church

Despite—or perhaps because of—the confusing array of Methodist denominations, close to 90 percent of church-going Alabamians in the late nineteenth century were either Baptist or Methodist. Handsome Methodist churches were conspicuous in every town, and Methodist schools and colleges were among the state’s best. Methodists were found in all walks of life, from the governor’s office to the iron furnaces to the sharecropper’s field. The three branches of black Methodism continued as separate denominations. But the Methodist Protestant Church (a small offshoot that began in the 1830s), the Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, united in 1939 to form the Methodist Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church united with United Evangelical Brethren to form the United Methodist Church. The 1960s were a difficult time for Methodists in Alabama, as they struggled with the issue of tearing down racial separation. In 1972, the black Central Alabama Conference was merged into the United Methodist Church’s other two Alabama conferences, the North Alabama and the Alabama-West Florida.

Maplesville United Methodist Church

Despite—or perhaps because of—the confusing array of Methodist denominations, close to 90 percent of church-going Alabamians in the late nineteenth century were either Baptist or Methodist. Handsome Methodist churches were conspicuous in every town, and Methodist schools and colleges were among the state’s best. Methodists were found in all walks of life, from the governor’s office to the iron furnaces to the sharecropper’s field. The three branches of black Methodism continued as separate denominations. But the Methodist Protestant Church (a small offshoot that began in the 1830s), the Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, united in 1939 to form the Methodist Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church united with United Evangelical Brethren to form the United Methodist Church. The 1960s were a difficult time for Methodists in Alabama, as they struggled with the issue of tearing down racial separation. In 1972, the black Central Alabama Conference was merged into the United Methodist Church’s other two Alabama conferences, the North Alabama and the Alabama-West Florida.

Today in Alabama, only Baptists outnumber Methodists, who remain committed to the theological, structural, and reform tradition begun by John Wesley.

Additional Resources

Brasher, John Lawrence. The Sanctified South: John Lakin Brasher and the Holiness Movement. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Collins, Donald E. When the Church Bell Rang Racist: The Methodist Church and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1998.

Hubbs, G. Ward. “Of Circuit Riders and Camp Meetings, Missionaries and Methodists.” Alabama Heritage 86 (Fall 2007): 18-25.

———. “A Settlement House in Ensley’s Italian District.” Alabama Heritage 75 (Winter 2005) 32-40.

Lazenby, Marion Elias. History of Methodism in Alabama and West Florida. Nashville: Methodist Publishing Co., Parthenon, 1960.

Stockham, Richard J. “The Misunderstood Lorenzo Dow.” Alabama Review 16 (January 1963): 20-34.

West, Anson. A History of Methodism in Alabama. Nashville: Publishing House, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, 1893.