Hugo L. Black

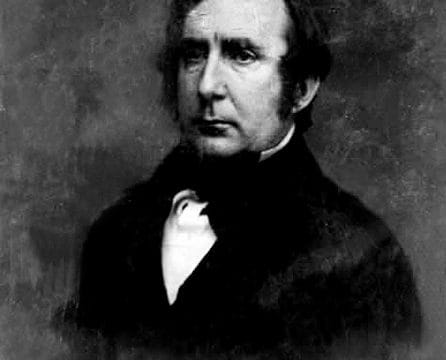

Hugo Black

Hugo Black (1886-1971) served in the U.S. Senate and on the U.S. Supreme Court for 34 years. He was America’s earliest prophet of the judicial revolution that established a national bill of rights for all persons subject to the U.S. Constitution. Shortly after his appointment to the Supreme Court, Black survived a national uproar over his prior, brief membership in Birmingham’s Ku Klux Klan and within two decades became arguably the most hated white man in the American South after he joined the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education outlawing racial segregation. Today, Justice Black is remembered as one of the nation’s foremost champions of the First Amendment and, in his words, the rights of the “weak, helpless, and outnumbered.”

Hugo Black

Hugo Black (1886-1971) served in the U.S. Senate and on the U.S. Supreme Court for 34 years. He was America’s earliest prophet of the judicial revolution that established a national bill of rights for all persons subject to the U.S. Constitution. Shortly after his appointment to the Supreme Court, Black survived a national uproar over his prior, brief membership in Birmingham’s Ku Klux Klan and within two decades became arguably the most hated white man in the American South after he joined the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education outlawing racial segregation. Today, Justice Black is remembered as one of the nation’s foremost champions of the First Amendment and, in his words, the rights of the “weak, helpless, and outnumbered.”

Hugo Black in Ashland

Hugo Lafayette Black was born in Harlan, a small community in southern Clay County, on February 27, 1886. Black’s early understanding of the world was shaped by the primary institutions of rural Alabama life: family, church, school, and courthouse. During these formative years, Black adored his deeply religious mother, Ardellah, and grew estranged from his father, William Lafayette Black, a conservative local merchant whose failure to repent for repeated bouts of public drunkenness prompted his expulsion from the local Baptist church. The family moved to the county seat, Ashland, in 1890. When not in school, Black spent much of his childhood in and around the Clay County courthouse attending political rallies or watching criminal trials.

Hugo Black in Ashland

Hugo Lafayette Black was born in Harlan, a small community in southern Clay County, on February 27, 1886. Black’s early understanding of the world was shaped by the primary institutions of rural Alabama life: family, church, school, and courthouse. During these formative years, Black adored his deeply religious mother, Ardellah, and grew estranged from his father, William Lafayette Black, a conservative local merchant whose failure to repent for repeated bouts of public drunkenness prompted his expulsion from the local Baptist church. The family moved to the county seat, Ashland, in 1890. When not in school, Black spent much of his childhood in and around the Clay County courthouse attending political rallies or watching criminal trials.

After his father’s death in September 1900, when he changed “Lafayette” to a middle initial, Black was expelled in a fight with teachers over the treatment of an older sister and failed to graduate from high school. Afterward, he attended Birmingham Medical College for a year and subsequently enrolled in law school at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa; he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1906. Black returned to Ashland and maintained a meager law practice until a fire destroyed half the town square including his law office. He then moved to Birmingham in September 1907.

As a young, struggling lawyer in the South’s only industrial city, Black became involved in the First Baptist Church and a wide range of civic groups and fraternal lodges, including the Knights of Pythias (a fraternal organization founded in Washington, D.C., in 1864). He helped to defend black and white miners arrested in the Birmingham miners’ strike of 1907. Black’s legal career improved dramatically when A. O. Lane, Birmingham’s newly appointed police commissioner and a fellow Pythian, appointed him in 1911 to be the part-time judge of Birmingham’s police court. Spotlighted in local newspapers, Black ardently enforced Alabama’s anti-liquor laws and generally gave all defendants swift, stern justice, regardless of race.

In 1914, after developing a rewarding private practice, Black successfully ran for Jefferson County prosecutor. As the county’s chief lawyer, Black dismissed thousands of cases involving alleged petty crimes by African Americans in the Birmingham area. He investigated and prosecuted cases of white police officers brutalizing and killing black suspects. On special assignment from Alabama Attorney General William Logan Martin, Black also helped to destroy one of the nation’s largest stockpiles of confiscated illegal liquor, discovered near the Chattahoochee River in present-day Phenix City. Black’s effective, aggressive style won him both friends and enemies, who ultimately maneuvered to constrain his office. As a result, Black resigned as Jefferson County prosecutor in 1917 and joined the U.S. Army during World War I. He rose to the rank of captain but saw no combat.

Returning in debt to Birmingham after the war, Black built a lucrative law practice by representing injured workers from Birmingham industries and mines. He also represented unions, including the United Miners Workers of America, virtually the only large, interracial organization in the Deep South at that time. Black defended the Alabama unions in litigation surrounding the 1920 race for the U.S. Senate and in Birmingham’s 1921 miners’ strike, which the Alabama militia and state industrialists crushed using violent, race-baiting tactics.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

At the same time, Black led state efforts in and outside of the courtroom to end convict leasing, the state practice of leasing prisoners as workers to private industries, especially Birmingham’s coal mines. Condemned as a modern form of deadly slavery for a majority of Alabama’s black prisoners, convict leasing had become a primary source of revenue for the Alabama state government in the nineteenth century. It also figured in the one and only case in which Black appeared as a lawyer before the U.S. Supreme Court. On February 23, 1921, Black married Josephine Foster, daughter of a prominent family and sister of future civil rights activist Virginia Foster Durr. The couple would have three children, Hugo Black Jr., Sterling Black, and Josephine Black Pesaresi.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

At the same time, Black led state efforts in and outside of the courtroom to end convict leasing, the state practice of leasing prisoners as workers to private industries, especially Birmingham’s coal mines. Condemned as a modern form of deadly slavery for a majority of Alabama’s black prisoners, convict leasing had become a primary source of revenue for the Alabama state government in the nineteenth century. It also figured in the one and only case in which Black appeared as a lawyer before the U.S. Supreme Court. On February 23, 1921, Black married Josephine Foster, daughter of a prominent family and sister of future civil rights activist Virginia Foster Durr. The couple would have three children, Hugo Black Jr., Sterling Black, and Josephine Black Pesaresi.

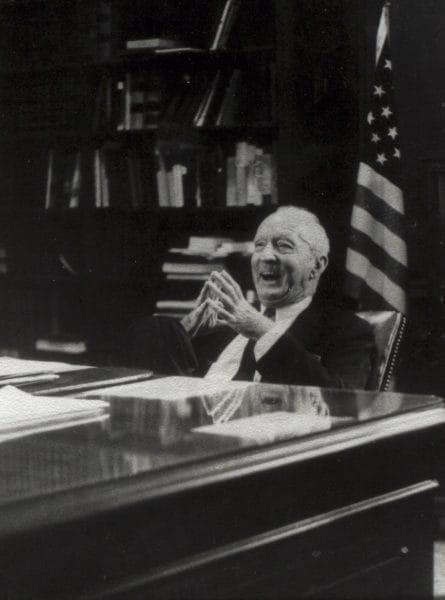

Sen. Hugo L. Black

In September 1923, after considerable delay and doubt, Black joined the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Almost 50 years later, in an interview published by agreement only after his death, Black stated that he joined the Klan because he considered it an “anti-corporation” force that helped to counter the political and social influence of industrialists and large corporations who had taken full control of the Alabama economy after the destruction of the state’s labor movement. In 1925, after incumbent U.S. senator Oscar W. Underwood indicated that he would not seek re-election, Black resigned from the Klan and announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate. Black won the Democratic nomination, which assured him of victory in the general election in 1926, after a campaign supporting prohibition, fighting “millionaire opponents,” and condemning the influence of money in politics. In an all-white election, an enlarged Klan vote across Alabama apparently split between Black and another Senate candidate, Breck Musgrove, but Black carried almost all Alabama counties where Baptists constituted a majority of white churchgoers.

Sen. Hugo L. Black

In September 1923, after considerable delay and doubt, Black joined the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Almost 50 years later, in an interview published by agreement only after his death, Black stated that he joined the Klan because he considered it an “anti-corporation” force that helped to counter the political and social influence of industrialists and large corporations who had taken full control of the Alabama economy after the destruction of the state’s labor movement. In 1925, after incumbent U.S. senator Oscar W. Underwood indicated that he would not seek re-election, Black resigned from the Klan and announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate. Black won the Democratic nomination, which assured him of victory in the general election in 1926, after a campaign supporting prohibition, fighting “millionaire opponents,” and condemning the influence of money in politics. In an all-white election, an enlarged Klan vote across Alabama apparently split between Black and another Senate candidate, Breck Musgrove, but Black carried almost all Alabama counties where Baptists constituted a majority of white churchgoers.

During his first term in the Senate, when Republicans controlled both houses of Congress and the presidency, Black had relatively little influence on the course of national legislation or public events, although he often spoke against “monied interests” and corrupt use of government for private corporate gain. Black won a second term in 1932, the same year that Democrats gained a majority in Congress and took control of the White House with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Hugo Black at Lincoln Memorial, 1939

Even before Roosevelt was inaugurated, Black introduced legislation to establish a minimum wage and to limit work in most large industries to 30 hours a week in order to spread available jobs to millions of workers who lost their jobs in the Great Depression. Six years later, Black’s substantially revised legislation became the Fair Labor Standards Act, America’s first minimum-wage law. Black’s Senate committee investigations prompted the reorganization of the nation’s airline and utility industries. While most southern members of Congress selectively supported New Deal proposals, Black usually voted for Roosevelt’s policies and often complained that the administration did not go far enough to help the lower classes.

Hugo Black at Lincoln Memorial, 1939

Even before Roosevelt was inaugurated, Black introduced legislation to establish a minimum wage and to limit work in most large industries to 30 hours a week in order to spread available jobs to millions of workers who lost their jobs in the Great Depression. Six years later, Black’s substantially revised legislation became the Fair Labor Standards Act, America’s first minimum-wage law. Black’s Senate committee investigations prompted the reorganization of the nation’s airline and utility industries. While most southern members of Congress selectively supported New Deal proposals, Black usually voted for Roosevelt’s policies and often complained that the administration did not go far enough to help the lower classes.

In August 1937, Roosevelt appointed Black to the U.S. Supreme Court, and he was confirmed by the Senate on August 17. A month later, the Pittsburg Post-Gazette used documents supplied by a former Alabama Klan leader to expose Black’s membership in the Ku Klux Klan. Despite a national uproar, led by anti-New Deal newspapers, Black refused to resign. In a national radio address, the first ever delivered by a member of the Supreme Court, Black explained that he abhorred racial and religious intolerance while acknowledging that he once belonged to the Klan.

Over more than three decades, Justice Black helped move the Supreme Court away from legal doctrine that had jeopardized New Deal reforms and wrote dozens of opinions. Many were dissents that later became law and included expanding the rights of free speech to those whom society considered unpopular, weak, poor, zealous, or hated. In 1947, Black wrote a dissent in Adamson v. California in which he contended that the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment endowed the American people with all the entitlements of the federal Bill of Rights that no local, state, or federal government official could lawfully ignore. Also that year, Black wrote a majority opinion proclaiming a constitutional mandate for a “wall of separation between church and state” in Everson v. Board of Education. Over the following two decades, Black’s judicial views about the application of the Bill of Rights and the separation of church and state were largely adopted by the Court.

U.S. Supreme Court Justices, 1957

In 1954, Black joined in the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion outlawing racial segregation in public education in Brown v. Board of Education, and, in effect, destroying the legal basis of American segregation. On September 11, 1957, he married Mary Elizabeth Seay DeMerritte (his first wife died in 1951). In 1963, Justice Black wrote the majority opinion in Gideon v. Wainwright, a decision that gave poor Americans facing imprisonment a right to a lawyer regardless of financial means. He joined his fellow justices in forcing the South to grant the constitutional right to vote to black citizens in Gomillion v. Lightfoot and in requiring all state legislatures to reapportion fairly in Baker v. Carr. In addition, Black wrote the Supreme Court’s opinion that banned religious prayers from the nation’s public schools in Engel v. Vitale.

U.S. Supreme Court Justices, 1957

In 1954, Black joined in the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion outlawing racial segregation in public education in Brown v. Board of Education, and, in effect, destroying the legal basis of American segregation. On September 11, 1957, he married Mary Elizabeth Seay DeMerritte (his first wife died in 1951). In 1963, Justice Black wrote the majority opinion in Gideon v. Wainwright, a decision that gave poor Americans facing imprisonment a right to a lawyer regardless of financial means. He joined his fellow justices in forcing the South to grant the constitutional right to vote to black citizens in Gomillion v. Lightfoot and in requiring all state legislatures to reapportion fairly in Baker v. Carr. In addition, Black wrote the Supreme Court’s opinion that banned religious prayers from the nation’s public schools in Engel v. Vitale.

Upon his death at the age of 85, Justice Black was buried in Arlington Cemetery, next to his first wife, Josephine Foster Black. Between the couple’s two modest grave markers stands a marble bench proclaiming simply: “Here lies a good man.”

Further Reading

- Black, Hugo. Mr. Justice and Mrs. Black: The Memoirs of Hugo L. Black and Elizabeth Black. New York: Random House, 1986.

- Black, Hugo, Jr. My Father, a Remembrance. New York: Random House, 1975.

- Dunne, Gerald T. Hugo Black and the Judicial Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977.

- Durr, Clifford J. “Mr. Justice Black: A Personal Appraisal.” Georgia Law Review 6 (Fall 1971): 1-16.

- Freyer, Tony A., ed. Justice Hugo Black and Modern America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

- Hamilton, Virginia Van der Veer. Hugo Black: The Alabama Years. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972.

- Meador, Daniel. Mr. Justice Black and His Books. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974.

- Newman, Roger K. Hugo Black. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

- Suitts, Steve. Hugo Black of Alabama: How His Roots and Early Career Shaped the Great Champion of the Constitution. Montgomery: New South Books, 2005.

- ———. Hugo Black of Alabama. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2017.