Creek War of 1813-14

Chief Menawa

The Creek War of 1813-14 began as a civil war, largely centered among the Upper Creeks, whose towns were located on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and upper reaches of the Alabama rivers. The struggle pitted a faction of the Creeks who became known as Red Sticks against those Creeks who supported the National Council, a relatively new body that had developed from the traditional regional meetings of headmen from the Creek towns. Under the auspices of federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins, the National Council’s authority and powers had been expanded. The war broke out against the backdrop of the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Americans, fearful that southeastern Indians would ally with the British, quickly joined the war against the Red Sticks, turning the civil war into a military campaign designed to destroy Creek power. To prove their loyalty to the United States, contingents of Choctaw and Cherokee warriors joined the American war against the Creeks. Thus, the Creek civil war was quickly transformed into a multidimensional war that resulted in the total defeat of the Creek people at the hands of American armies and their Native American allies.

Chief Menawa

The Creek War of 1813-14 began as a civil war, largely centered among the Upper Creeks, whose towns were located on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and upper reaches of the Alabama rivers. The struggle pitted a faction of the Creeks who became known as Red Sticks against those Creeks who supported the National Council, a relatively new body that had developed from the traditional regional meetings of headmen from the Creek towns. Under the auspices of federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins, the National Council’s authority and powers had been expanded. The war broke out against the backdrop of the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Americans, fearful that southeastern Indians would ally with the British, quickly joined the war against the Red Sticks, turning the civil war into a military campaign designed to destroy Creek power. To prove their loyalty to the United States, contingents of Choctaw and Cherokee warriors joined the American war against the Creeks. Thus, the Creek civil war was quickly transformed into a multidimensional war that resulted in the total defeat of the Creek people at the hands of American armies and their Native American allies.

The Roots of Conflict

The complex causes of the war can be traced to the declining economic situation among southeastern Indian groups, the resentments caused by increasing accommodation of American demands by the Creek National Council, the increasing pressure from expanding white settlement along Creek borders (particularly along the newly constructed Federal Road), and a reactionary religious movement. By 1812, the Creek National Council agreed to use annuity payments from the U.S. government for sales of hunting lands to retire the debts of major Creek debtors—an action that antagonized many Creeks. By 1813, the hunting and trading economy of the eighteenth century was largely on the decline, and growing numbers of Creeks were adopting herding and agriculture geared toward the emerging market economy. As a result, there was an increasing disparity in wealth and access to imported foreign goods, which were growing ever more expensive. Lacking an industrial base, Creeks were completely dependent on imported goods, including cloth, tools, and weaponry. The United States provided limited amounts of goods through trading stores, or “factories,” but the Creeks got the majority of their supplies from the Florida-based Panton, Leslie and Company and its successor, John Forbes and Company.

In addition, Creek resentment was growing over expanding settlements of Americans along the Creek-Georgia border and in the Cumberland Valley. By the spring of 1812, Creek representatives had met with Shawnee leaders on the Ohio River regarding the possibility of obtaining arms from the British. Shawnee-Creek diplomacy and concern over white encroachment dated to the mid-eighteenth century and at the time, the Shawnee were undergoing a revitalization movement and purposely urging those from other tribes to resist white encroachment. A small number of Creek warriors took action against the unwelcome settlers and killed two families near the Duck River in what is now Tennessee as well as two men along the Federal Road. Federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins called for the immediate execution of the guilty and threatened the Creeks with federal intervention if the murderers were not executed. The National Council, headed by Tuckabatchee leader Big Warrior, complied and ordered the execution of eight Creeks.

William McIntosh

In January 1813, another group of whites was murdered by a small party of Creeks in communication with the Shawnee, and Hawkins again pressed the Creek National Council to act quickly and punish the offenders. The council sent out warriors, known as the Law Menders, led by William McIntosh (Tustunnuggee Hutkee) of Coweta to execute the dissidents, who were largely from the Upper Creek Towns. Traditionally, such matters had been handled by clans, rather than the council. Thus, in spite of their intentions to preserve peace with the United States, this action by the council split the Creek Nation. The dissidents, attempting to subsist in a broken economy in which only a few prospered and resenting the increasing border encroachments and traffic along the contested Federal Road, acted against the council. These Creek dissidents blamed the expanding conflict on the relatively new exercises of power by the National Council. The executions came at a time of intense religious prophecy among many Native American groups that urged a spiritual awakening and a return to pre-contact traditions combined with a denunciation of foreign influences and the use of armed force if necessary to regain Indian land. Creek prophets, influenced by the Shawnee brothers Tenskwatawa (known as The Prophet) and Tecumseh, gained adherents, especially among Creek traditionalists who resented the infringement of traditional clan authority that the Creek National Council had assumed in ordering the execution of leading warriors.

William McIntosh

In January 1813, another group of whites was murdered by a small party of Creeks in communication with the Shawnee, and Hawkins again pressed the Creek National Council to act quickly and punish the offenders. The council sent out warriors, known as the Law Menders, led by William McIntosh (Tustunnuggee Hutkee) of Coweta to execute the dissidents, who were largely from the Upper Creek Towns. Traditionally, such matters had been handled by clans, rather than the council. Thus, in spite of their intentions to preserve peace with the United States, this action by the council split the Creek Nation. The dissidents, attempting to subsist in a broken economy in which only a few prospered and resenting the increasing border encroachments and traffic along the contested Federal Road, acted against the council. These Creek dissidents blamed the expanding conflict on the relatively new exercises of power by the National Council. The executions came at a time of intense religious prophecy among many Native American groups that urged a spiritual awakening and a return to pre-contact traditions combined with a denunciation of foreign influences and the use of armed force if necessary to regain Indian land. Creek prophets, influenced by the Shawnee brothers Tenskwatawa (known as The Prophet) and Tecumseh, gained adherents, especially among Creek traditionalists who resented the infringement of traditional clan authority that the Creek National Council had assumed in ordering the execution of leading warriors.

Creeks Divide

As Creek warriors rose against their National Council and threatened the traditional seats of power in Tuckabatchee and Coweta, Benjamin Hawkins ruled out any hope of reconciliation when he called on the Creeks to renounce the dissidents and “prophets.” Hawkins made it clear that those who did not fight the dissidents were America’s enemies, given the widely held belief that a September 1811 visit by Tecumseh had aimed to form a pan-Indian confederation to fight white expansion. The Shawnee call for unity and armed resistance to American expansion was accompanied by “new war songs and dances” as well as prophetic messages. The occurrence of comets and earthquakes seemed to confirm the messages of the prophets. The call for rejection of the American system, armed resistance to American expansion, and revitalization of Creek culture found receptive ears.

The dissidents’ objective was Tuckabatchee, home to one of the leading chiefs on the National Council, where residents began erecting defensive works, as did those in Cusseta and Coweta. In addition to assaulting Tuckabatchee, dissidents attacked accomodationist headmen and, in the Upper Towns, began a systematic slaughter of domestic animals, most of which belonged to men who had gained power by adopting aspects of European culture. Many of those who committed these acts believed that domesticated animals perverted the natural order in which animals were meant to live in the woods. The slaughter, however, condemned the Creeks to hunger during the war. Deer herds had been dramatically reduced, and with men occupied in war, trade disrupted, and ammunition scarce, hunting was often sharply curtailed.

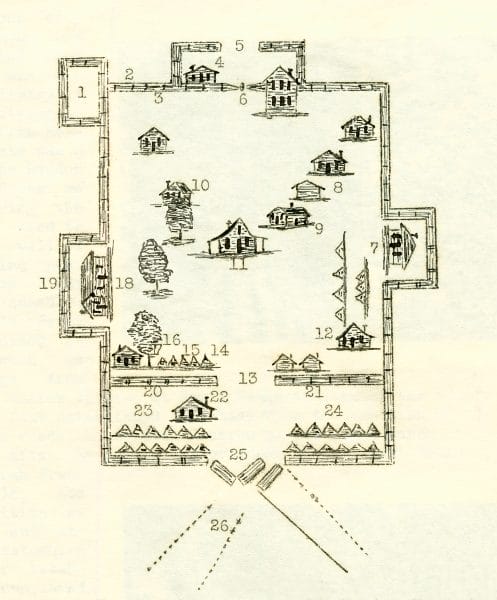

Diagram of Fort Mims

In preparation for action against the National Council, the dissidents travelled to Pensacola to seek ammunition and assistance from the Spanish government. On their return home, they were attacked by Mississippi militia and Tensaw area settlers who wanted to prevent Spanish ammunition from reaching the main body of disaffected warriors. The attack on July 27, 1813, near Burnt Corn Creek (in present-day Escambia County near Brewton), changed and escalated the nature of the war. In retaliation for the attack at Burnt Corn, the dissidents turned their fury on the fortified settlement of Samuel Mims. These dissidents were soon called Red Sticks because they had raised the “red stick of war,” a favored weapon and symbolic Creek war declaration. The brutal attack on Fort Mims on August 30, 1813, by nearly 700 Red Sticks was a complete victory and left 250 of the defenders and civilian inhabitants dead, with perhaps 100 others taken captive by the Red Sticks. Sporadic attacks were likewise launched against American settlers along the Chattahoochee River, and among the Upper Towns, support for the Red Sticks expanded rapidly.

Diagram of Fort Mims

In preparation for action against the National Council, the dissidents travelled to Pensacola to seek ammunition and assistance from the Spanish government. On their return home, they were attacked by Mississippi militia and Tensaw area settlers who wanted to prevent Spanish ammunition from reaching the main body of disaffected warriors. The attack on July 27, 1813, near Burnt Corn Creek (in present-day Escambia County near Brewton), changed and escalated the nature of the war. In retaliation for the attack at Burnt Corn, the dissidents turned their fury on the fortified settlement of Samuel Mims. These dissidents were soon called Red Sticks because they had raised the “red stick of war,” a favored weapon and symbolic Creek war declaration. The brutal attack on Fort Mims on August 30, 1813, by nearly 700 Red Sticks was a complete victory and left 250 of the defenders and civilian inhabitants dead, with perhaps 100 others taken captive by the Red Sticks. Sporadic attacks were likewise launched against American settlers along the Chattahoochee River, and among the Upper Towns, support for the Red Sticks expanded rapidly.

The Conflict Grows

Holy Ground Battlefield Park

Following the attack on Fort Mims and the ensuing escalation, the divided Creek towns faced an invasion of their country by military forces from Mississippi, Georgia, and Tennessee. The sprawling and open lay-out of Creek towns, however, made them difficult to defend or fortify. Creek prophets cast “magic” incantations and spiritual barriers to protect warriors and locations from bullets, and the Red Stick leadership fortified towns and removed noncombatants from exposed locations. Moreover, the embattled towns sought strength in numbers, relocating scattered residents to fortified centers, one for each of the three major Creek divisions. The Alabama towns collected at the Econochaca (Holy Ground), Tallapoosas congregated near Autossee, and the Red Stick Abeikas (primarily Okfuskees) took refuge behind a formidable barrier they erected at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend). These hastily constructed positions became the focus of American attacks.

Holy Ground Battlefield Park

Following the attack on Fort Mims and the ensuing escalation, the divided Creek towns faced an invasion of their country by military forces from Mississippi, Georgia, and Tennessee. The sprawling and open lay-out of Creek towns, however, made them difficult to defend or fortify. Creek prophets cast “magic” incantations and spiritual barriers to protect warriors and locations from bullets, and the Red Stick leadership fortified towns and removed noncombatants from exposed locations. Moreover, the embattled towns sought strength in numbers, relocating scattered residents to fortified centers, one for each of the three major Creek divisions. The Alabama towns collected at the Econochaca (Holy Ground), Tallapoosas congregated near Autossee, and the Red Stick Abeikas (primarily Okfuskees) took refuge behind a formidable barrier they erected at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend). These hastily constructed positions became the focus of American attacks.

The attack on Fort Mims and its civilian inhabitants, many of whom were of Creek ancestry, outraged Americans and immediately changed the course of the war. Red Sticks followed up their attack on Fort Mims with smaller attacks against nearby Fort Sinquefield. American retaliation for the attack on Fort Mims was loosely but ineffectively coordinated by a series of American military commanders, notably Gen. Thomas Flournoy, the commander of the Seventh Military District, as well as the governors of Georgia, Tennessee, and the Mississippi Territory. The Americans’ hastily devised plan called for a three-pronged invasion of Creek country in which the three armies were to rendezvous along the Tallapoosa River. By October 1813, the invasion was underway, largely without regard for training new recruits and volunteers or the establishment of clear communication channels and supply chains.

John Coffee

Gov. William Blount of Tennessee called for 3,500 volunteers from across the state to be mustered in two armies, led by rival commanders: John Cocke and Andrew Jackson, whose West Tennessee militia of 1,000 men was supported by 1,300 cavalry commanded by John Coffee. Jackson’s force was also supplemented by a sizeable contingent of Cherokee warriors. Their objective was to attack the Red Sticks among the Abeika towns. By November 3, Jackson secured the first American victory in the war when Coffee’s cavalry routed Creeks at the town of Tullusahatchee, killing 200 Red Stick warriors as well as a number of women and children. A few days later, a large Red Stick force laid siege to the Creek town of Talladega. Jackson attempted to encircle the town, but most of the approximately 1,000 attackers managed to escape, although with heavy losses of perhaps one-third of their warriors. Meanwhile, Hillabee residents sent word to Jackson that they did not intend to support the Red Stick faction. Without Jackson’s knowledge, Cocke sent a contingent of his army to attack the town, killing roughly 70 warriors and capturing nearly 300. Those who escaped joined the Red Sticks. Supply problems, short enlistments, poor communications, and quarrels between Jackson and Cocke plagued the Tennessee forces, and by year’s end, Jackson was left with approximately 150 men at Fort Strother on the Coosa River.

John Coffee

Gov. William Blount of Tennessee called for 3,500 volunteers from across the state to be mustered in two armies, led by rival commanders: John Cocke and Andrew Jackson, whose West Tennessee militia of 1,000 men was supported by 1,300 cavalry commanded by John Coffee. Jackson’s force was also supplemented by a sizeable contingent of Cherokee warriors. Their objective was to attack the Red Sticks among the Abeika towns. By November 3, Jackson secured the first American victory in the war when Coffee’s cavalry routed Creeks at the town of Tullusahatchee, killing 200 Red Stick warriors as well as a number of women and children. A few days later, a large Red Stick force laid siege to the Creek town of Talladega. Jackson attempted to encircle the town, but most of the approximately 1,000 attackers managed to escape, although with heavy losses of perhaps one-third of their warriors. Meanwhile, Hillabee residents sent word to Jackson that they did not intend to support the Red Stick faction. Without Jackson’s knowledge, Cocke sent a contingent of his army to attack the town, killing roughly 70 warriors and capturing nearly 300. Those who escaped joined the Red Sticks. Supply problems, short enlistments, poor communications, and quarrels between Jackson and Cocke plagued the Tennessee forces, and by year’s end, Jackson was left with approximately 150 men at Fort Strother on the Coosa River.

The Georgia militia, under Gen. John Floyd, had actually been in the field first, with limited action against Red Sticks along the Chattahoochee River, near the allied Creek town of Coweta in August and September. The nearly 1,000 Georgians set out for the Tallapoosa towns at roughly the same time that the Tennesseans moved toward the Abeika heartland in October, building a string of fortified supply depots as they proceeded. Floyd’s army was assisted by a contingent of 400 Creek warriors under William McIntosh. Floyd’s main objective was the Red Stick stronghold at Autossee. His men attacked and burned the town on November 29, 1813, but could not surround it. Most of the inhabitants escaped, but the defenders lost an estimated 200 warriors to only 11 American dead and just over 50 wounded, including Floyd. He retreated to Fort Mitchell, a supply post he had established earlier on the Chattahoochee River.

Canoe Fight

Gen. Ferdinand Claiborne, whose troops included Mississippi Territory militia, poorly trained and equipped volunteers who had joined after the Mims massacre, and Choctaw warriors, commanded the third arm of the American invasion force. In the early fall of 1813, after several minor skirmishes along the Alabama River, including Samuel Dale’s famous “canoe fight,” Claiborne’s troops made for their main objective, the Holy Ground, a settlement located on the bluffs above the Alabama River, approximately 30 miles west of present-day Montgomery, which they attacked on December 23, 1813. Most of the Red Sticks escaped, however. After pillaging the town for corn, Claiborne’s troops burned the town and retreated south and disbanded.

Canoe Fight

Gen. Ferdinand Claiborne, whose troops included Mississippi Territory militia, poorly trained and equipped volunteers who had joined after the Mims massacre, and Choctaw warriors, commanded the third arm of the American invasion force. In the early fall of 1813, after several minor skirmishes along the Alabama River, including Samuel Dale’s famous “canoe fight,” Claiborne’s troops made for their main objective, the Holy Ground, a settlement located on the bluffs above the Alabama River, approximately 30 miles west of present-day Montgomery, which they attacked on December 23, 1813. Most of the Red Sticks escaped, however. After pillaging the town for corn, Claiborne’s troops burned the town and retreated south and disbanded.

By January 1814, both Jackson and Floyd had managed to raise recruits and organize supplies for additional campaigns. Action in the new year began when Floyd headed west from Fort Mitchell to extend his supply line. After building Fort Hull, a small post 40 miles west of Fort Mitchell, he proceeded to Calabee Creek. There, his camp was surprised in the early dawn by a large force of Red Sticks that attacked with war clubs and tomahawks but could not overpower Floyd’s artillery. Timpoochee Barnard, leading the allied Yuchi Creeks, was instrumental in saving a company of Georgians who had been nearly overwhelmed by Red Sticks. The Red Sticks lost 50 men, while the Georgians and their Creek allies lost 22 men, with 150 wounded. After the battle, Floyd’s army retreated to Georgia.

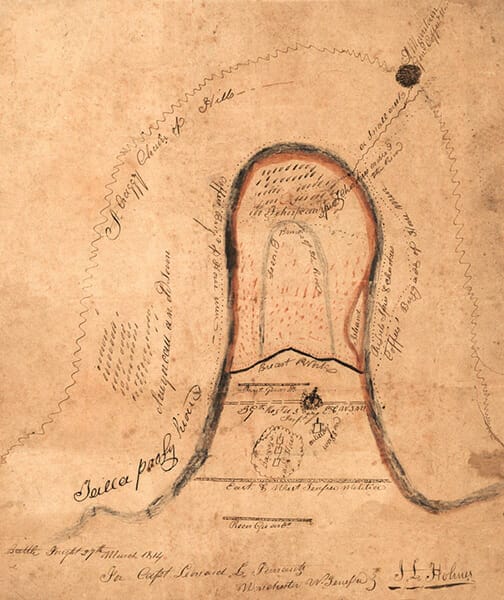

Map of Horseshoe Bend

Thus, by the middle of January, only one American army remained active—that of Andrew Jackson; the army of 60-day enlistees had expanded to nearly 1,000 men. Seeking to defeat the Red Sticks before his army dissolved again, Jackson moved south from Fort Strother. By the end of the month, he had engaged the enemy at Emuckfau Creek and Enitachopco Creek with little success. The arrival of the 600-man Thirty-ninth U.S. Infantry Regiment allowed Jackson to embark on an ambitious campaign against the single largest remaining Red Stick settlement: Tohopeka at the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River. There, on March 27, aided by Cherokee and Creek allies, Jackson’s army routed the Red Sticks, killing nearly all of the estimated 800 warriors who had gathered behind an impressive barricade. From Horseshoe Bend, Jackson proceeded along the Tallapoosa River, burning towns and improvements in his path, until he reached the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, where he built Fort Jackson, the site of the earlier French post, Fort Toulouse. In addition to dispatching scouting parties who attacked any Creeks they encountered, Americans also burned virtually every town in the Upper Creek Nation, nearly 50 in all.

Map of Horseshoe Bend

Thus, by the middle of January, only one American army remained active—that of Andrew Jackson; the army of 60-day enlistees had expanded to nearly 1,000 men. Seeking to defeat the Red Sticks before his army dissolved again, Jackson moved south from Fort Strother. By the end of the month, he had engaged the enemy at Emuckfau Creek and Enitachopco Creek with little success. The arrival of the 600-man Thirty-ninth U.S. Infantry Regiment allowed Jackson to embark on an ambitious campaign against the single largest remaining Red Stick settlement: Tohopeka at the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River. There, on March 27, aided by Cherokee and Creek allies, Jackson’s army routed the Red Sticks, killing nearly all of the estimated 800 warriors who had gathered behind an impressive barricade. From Horseshoe Bend, Jackson proceeded along the Tallapoosa River, burning towns and improvements in his path, until he reached the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, where he built Fort Jackson, the site of the earlier French post, Fort Toulouse. In addition to dispatching scouting parties who attacked any Creeks they encountered, Americans also burned virtually every town in the Upper Creek Nation, nearly 50 in all.

The death rate during the various Creek war battles was high, with estimates ranging from 1,500 to 3,000. Whatever the number, the Red Sticks themselves represented their numerous losses to agent Benjamin Hawkins as “like the fall of leaves.” The death toll among noncombatants continued to climb after hostilities ceased, primarily from starvation and exposure. Uncounted numbers of refugees headed for Florida and resettled among the Seminoles.

Aftermath

After the defeat at Horseshoe Bend, Red Sticks began surrendering in large numbers. Many of their leaders preferred to surrender and take their chances with Andrew Jackson rather than face death at the hands of their own people, who blamed them for their destitution. Others led their people into canebrakes and swamps to hide.

It was under these circumstances that Jackson called Creek leaders to Fort Jackson to hear the terms for peace. With most Upper Creek headmen either killed in battle, in hiding, or under arrest, representatives of the National Council, representing a variety of towns including Coweta, Tuckabatchee, Hillabee, Coosa, and Tuskegee, signed the treaty on August 9, 1814. The cession of land demanded by the United States as payment for the cost of the war encompassed more than 20 million acres west of the Coosa River (the hunting territory of the Abeika) as well as a swath of land to the south of the Tallapoosa River and north of the border with Florida that reached from the Tombigbee River to the St. Marys River—in effect, taking a good deal of Tallapoosa and Lower Creek land, including some Alabama town sites. The treaty also purported to erect a buffer between the Creek towns and potential Spanish suppliers at Pensacola. Even though many Creeks objected to the treaty, they had little choice but to agree to Jackson’s terms.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Creek War is sometimes portrayed by historians as a war between the two major divisions of the Creeks: the Upper and Lower Towns. Others have attempted to portray it as a conflict of Muskogean speakers vs. non-Muskogean Creeks, such as the Alabamas and the Yuchis. Some have viewed the conflict as one in which traditionalist Red Sticks attacked acculturated or “progressive” Creeks, such as those seeking shelter at Fort Mims. None of these interpretations are supported by facts. Although the majority of the action was among the Upper Towns and the divisions there were greatest, some Lower Creeks supported the Red Stick faction. On the other hand, many Upper Creeks not only opposed the Red Sticks, they also fought against them. Likewise, whereas many Alabama Indians sided with the Red Sticks, the Yuchi and Natchee Creek Indians (also non-Muskogean speakers) fought on the side of the national Creeks. And notable warriors of mixed ancestry fought on both sides, the most famous of whom are William Weatherford for the Red Sticks and William McIntosh with the national Creeks. Nor was the divide simply between the “haves” and “have nots.” Perhaps the greatest Red Stick hero of the war, Menawa, was reported to be the wealthiest Upper Creek before the conflict.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Creek War is sometimes portrayed by historians as a war between the two major divisions of the Creeks: the Upper and Lower Towns. Others have attempted to portray it as a conflict of Muskogean speakers vs. non-Muskogean Creeks, such as the Alabamas and the Yuchis. Some have viewed the conflict as one in which traditionalist Red Sticks attacked acculturated or “progressive” Creeks, such as those seeking shelter at Fort Mims. None of these interpretations are supported by facts. Although the majority of the action was among the Upper Towns and the divisions there were greatest, some Lower Creeks supported the Red Stick faction. On the other hand, many Upper Creeks not only opposed the Red Sticks, they also fought against them. Likewise, whereas many Alabama Indians sided with the Red Sticks, the Yuchi and Natchee Creek Indians (also non-Muskogean speakers) fought on the side of the national Creeks. And notable warriors of mixed ancestry fought on both sides, the most famous of whom are William Weatherford for the Red Sticks and William McIntosh with the national Creeks. Nor was the divide simply between the “haves” and “have nots.” Perhaps the greatest Red Stick hero of the war, Menawa, was reported to be the wealthiest Upper Creek before the conflict.

In recent times, some historians have adopted the name “White Sticks” for the national Creeks. This designation has no basis in fact or in Creek custom. The Red Sticks took their name from their red war clubs, and to raise the “red club of war” literally meant to declare war. All war clubs were painted red, the emblematical color of blood and war, and national Creeks as well as Red Sticks employed them in battle during the war. The clubs, made from a straight piece of white oak or other suitable wood with a curved end, were roughly three feet long.

Following the war, the Creek people rebuilt their towns and economy. The National Council, under the leadership of many Creek War veterans, would direct the Creek response to increasing pressure by Americans for Creek land. By 1825, the power of the National Council was not contested by the Creek people, and they united behind it when law-menders dispatched by the National Council, led by the former Red Stick leader Menawa, executed William McIntosh for illegally ceding Creek land in Georgia. After his victory at Horseshoe Bend and his later victory at New Orleans against the British, Andrew Jackson achieved national fame and was elected to the presidency in 1828, based on his status as a war hero and a proponent of Indian Removal. Ironically, the man regarded as the leader of the Red Stick Creeks at Fort Mims, William Weatherford, withdrew from tribal affairs. His family remained in Alabama when the Creek people were forcibly removed from the state in the 1830s.

Further Reading

- Halbert, Henry S., and Timothy H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Edited by Frank L. Owsley Jr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 1997.

- Owsley, Frank L., Jr. Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812-1815. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981.

- Waselkov, Gregory A. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-14. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.