Mobile

RSA Buildings in Mobile

Founded by the French in 1702, Mobile is Alabama’s oldest city and a major port facility for the region. The city’s three centuries of history have been inextricably tied to the development of its port and the economic prosperity of the adjoining area. The city hosted the first Mardi Gras festivities in North America and has a rich cultural heritage. Mobile was the final destination of the last enslaved Africans brought to the United States shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. During the turbulent years of the civil rights movement, Mobile earned a reputation of tolerance in part because of the absence of violent demonstrations seen in many southern cities. Today, Mobile continues to serve a crucial economic role as a major port facility for the state and region. Notable people from Mobile include baseball greats Satchel Paige, Billy Williams, Theodore “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Willie McCovey, Hank Aaron, and Ozzie Smith. Famous figures in the arts include William March, Albert Murray, James Reese Europe, John Augustus Walker, Eugene Sledge, Eugene Walter, and Julian Lee Rayford. For these connections, the city is a stop on the Southern Literary Trail.

RSA Buildings in Mobile

Founded by the French in 1702, Mobile is Alabama’s oldest city and a major port facility for the region. The city’s three centuries of history have been inextricably tied to the development of its port and the economic prosperity of the adjoining area. The city hosted the first Mardi Gras festivities in North America and has a rich cultural heritage. Mobile was the final destination of the last enslaved Africans brought to the United States shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. During the turbulent years of the civil rights movement, Mobile earned a reputation of tolerance in part because of the absence of violent demonstrations seen in many southern cities. Today, Mobile continues to serve a crucial economic role as a major port facility for the state and region. Notable people from Mobile include baseball greats Satchel Paige, Billy Williams, Theodore “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Willie McCovey, Hank Aaron, and Ozzie Smith. Famous figures in the arts include William March, Albert Murray, James Reese Europe, John Augustus Walker, Eugene Sledge, Eugene Walter, and Julian Lee Rayford. For these connections, the city is a stop on the Southern Literary Trail.

Early History

Spanish explorer Alonzo Álvarez Pineda first explored the area that would become Mobile in 1519 during a voyage on which he charted much of the Gulf of Mexico. Pineda met with local Indian groups in the interior along the Mobile River. Two decades later, Hernando de Soto, travelled to the area in search for gold. Unlike Pineda, de Soto’s encounters with local Indian peoples were violent and many Spanish troops and Indians were killed. In 1559, a final Spanish explorer, Tristán de Luna, established a short-lived settlement near Mobile. After a hurricane devastated the expedition, the Spanish government abandoned its search for gold in the area. It would be another century before a European country explored the lower Gulf Coast.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

French interests in the region prompted the settlement of Mobile in 1702 by naval hero Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. But this city was located up the Mobile River, near Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, rather than at the mouth of the river.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

French interests in the region prompted the settlement of Mobile in 1702 by naval hero Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. But this city was located up the Mobile River, near Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, rather than at the mouth of the river.

Life in Old Mobile was difficult. Frequent floods and epidemics plagued the colonists. More dangerous, however, were the raids from Alabama Indians, who attacked the colonists and the Mauvila Indians who lived near their fort. When an attack damaged the fort at Old Mobile beyond repair, Bienville finally convinced the colonists to move the city closer to the mouth of Mobile Bay and away from danger. Many of the Mobilian Indians relocated with the colonists.

Colonial Mobile was a city of limited size and potential, largely because of the stagnant economic prospects of the French (1702-1763), British (1763-1780) and Spanish (1780-1813) settlements in the New World. Mobile was, however, a key settlement along the Gulf of Mexico, and its location near the deep waters of the Gulf was coveted by the European powers seeking to gain a foothold in the region. It was the capital of French Louisiana until 1720 and, for a short time in the 1760s served as the temporary capitol of British West Florida until the seat of government was moved to Pensacola. From 1780-81, Spanish military leader José Manuel de Ezpeleta served as governor of the Mobile District of Spanish West Florida. By the time Mobile became an American city in 1813, its population had already become multicultural, a trait that would distinguish it among other Alabama cities throughout its history. Yet it was not until American investment provided Mobile with much needed capital to make improvements and strengthened its economic standing that the city experienced true growth. On November 20, 1818, just prior to Alabama’s statehood, the Alabama Territorial Legislature charter the city’s first bank, the Bank of Mobile, which would operate in the city until 1884. Wealthy businessmen financed new building projects that enhanced the potential of the city’s port. By the 1820s, Mobile became a major exporting center for Alabama and the South to markets in the northeast and Europe. Cotton proved to be the most profitable export of antebellum Mobile, and the city’s economic fortunes prospered along with the wealthy plantations of the interior region.

Battle of Mobile Bay

The Civil War brought an end to Mobile’s prosperity, as a U.S. naval blockade stifled foreign trade. In August 1864, Union admiral David Farragut’s fleet of ships broke through Confederate defenses and entered Mobile Bay. The city itself was spared the devastation of other southern ports such as Charleston and New Orleans, but in late May 1865, a waterfront armory with 200 tons of ordnance exploded, killing 300 workers and devastating the waterfront facilities. The city was forced to rebuild a large portion of its port, which slowed its postwar recovery. The year after the war ended, Civil War veteran Joseph Stillwell Cain revived the Mobile’s Mardi Gras tradition with a parade through the city.

Battle of Mobile Bay

The Civil War brought an end to Mobile’s prosperity, as a U.S. naval blockade stifled foreign trade. In August 1864, Union admiral David Farragut’s fleet of ships broke through Confederate defenses and entered Mobile Bay. The city itself was spared the devastation of other southern ports such as Charleston and New Orleans, but in late May 1865, a waterfront armory with 200 tons of ordnance exploded, killing 300 workers and devastating the waterfront facilities. The city was forced to rebuild a large portion of its port, which slowed its postwar recovery. The year after the war ended, Civil War veteran Joseph Stillwell Cain revived the Mobile’s Mardi Gras tradition with a parade through the city.

Modernization

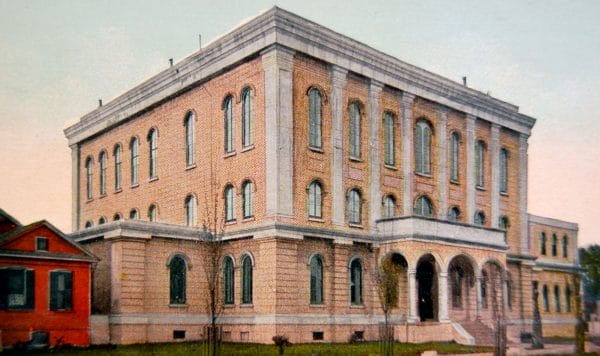

Medical College of Alabama

The early years of the New South were unkind to Alabama’s port city. The population fell as the cotton-dependent economy languished. In 1879, the city was on the verge of complete economic collapse and bankruptcy. Seeing the need to prevent such a disastrous event from threatening the state’s only port, the Alabama legislature repealed the city’s charter. This action effectively put the city under the control of a state-appointed committee, and the city’s operating budget was capped at $100,000 per year. This arrangement lasted until 1886, by which time timber had replaced cotton as the chief export. Municipal improvements attested to the city’s recovery. As Mobile entered the twentieth century, the port authorities had overseen an increase in its imports of bananas from South America and made plans to deepen its shipping channel.

Medical College of Alabama

The early years of the New South were unkind to Alabama’s port city. The population fell as the cotton-dependent economy languished. In 1879, the city was on the verge of complete economic collapse and bankruptcy. Seeing the need to prevent such a disastrous event from threatening the state’s only port, the Alabama legislature repealed the city’s charter. This action effectively put the city under the control of a state-appointed committee, and the city’s operating budget was capped at $100,000 per year. This arrangement lasted until 1886, by which time timber had replaced cotton as the chief export. Municipal improvements attested to the city’s recovery. As Mobile entered the twentieth century, the port authorities had overseen an increase in its imports of bananas from South America and made plans to deepen its shipping channel.

Waterman Globe

A combination of Progressive Era politics and Victorian morality contributed to Mobile’s development in the early twentieth century. Streetcar and telephone service expanded and the city adopted the commission form of government in 1911. Yet progress was again hampered by war. The port grew stagnant following the outbreak of World War I in Europe as countries recalled trade vessels for military service. The decline in port activity caused many workers to leave Mobile in search of more work. After the United States entered the war, the city was confronted with a job deficit of 10,000 skilled port workers. As a consequence of the city’s poor planning, Mobile’s shipyards produced only one ship before the end of World War I. Following the war, Mobile’s wealthy businessmen invested heavily in port improvements. Leading the effort were John B. Waterman, C. W. Hempstead, and Walter D. Bellingrath, whose personal gardens would soon become one of the area’s greatest tourist attractions. These three men founded the Waterman Steamship Corporation in 1919. The corporation became one of the largest shipping companies in the region and its owners and other entrepreneurs lobbied successfully for the creation of the Alabama State Docks in 1922. In 1927, the city constructed the Cochran bridge, a 10-mile structure spanning the five rivers that flow into Mobile Bay. The bridge quickened travel time between Mobile and the Eastern Shore, which brought added economic and civic benefits.

Waterman Globe

A combination of Progressive Era politics and Victorian morality contributed to Mobile’s development in the early twentieth century. Streetcar and telephone service expanded and the city adopted the commission form of government in 1911. Yet progress was again hampered by war. The port grew stagnant following the outbreak of World War I in Europe as countries recalled trade vessels for military service. The decline in port activity caused many workers to leave Mobile in search of more work. After the United States entered the war, the city was confronted with a job deficit of 10,000 skilled port workers. As a consequence of the city’s poor planning, Mobile’s shipyards produced only one ship before the end of World War I. Following the war, Mobile’s wealthy businessmen invested heavily in port improvements. Leading the effort were John B. Waterman, C. W. Hempstead, and Walter D. Bellingrath, whose personal gardens would soon become one of the area’s greatest tourist attractions. These three men founded the Waterman Steamship Corporation in 1919. The corporation became one of the largest shipping companies in the region and its owners and other entrepreneurs lobbied successfully for the creation of the Alabama State Docks in 1922. In 1927, the city constructed the Cochran bridge, a 10-mile structure spanning the five rivers that flow into Mobile Bay. The bridge quickened travel time between Mobile and the Eastern Shore, which brought added economic and civic benefits.

Mobile weathered the Great Depression far better than Alabama cities like Birmingham. The Port City’s two largest exports—cotton and timber—were less vulnerable to the fluctuations of the stock market. But there were still hardships. Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal brought much-needed jobs to the area. In 1938, the Works Progress Administration began building the Bankhead Tunnel, a one-mile underwater tunnel on Highway 90 completed in 1941. On the eve of World War II, Mobile’s economic future was promising. But the changes on the horizon were beyond any expectation.

ADDSCO Workers in Mobile

Wartime mobilization during World War II transformed Mobile into a shipbuilding city. The city quickly became the most crowded in the United States, and tensions rose as workers, white and black, fought over limited space and jobs. Between 1940 and 1943, 89,000 war workers descended on the city in an unprecedented expansion of Mobile’s population. By the end of the war, the population of Mobile County had increased by more than 60 percent. Mobile shipyards completed hundreds of ships for wartime service. In 1943, a race riot at the Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company occurred after company executives promoted 12 African Americans to the position of welder in response to Roosevelt’s executive order on fair employment. Brookley Field, established in 1941 as an air-supply depot and expanded after the United States entered the war, became the city’s largest postwar employer for two decades. The economic boom created by Brookley Field led to a sense of complacency among city leaders, who did not actively seek out new industry. The closure of the base in the 1960s contributed to Mobile’s stagnating economy for more than a decade.

ADDSCO Workers in Mobile

Wartime mobilization during World War II transformed Mobile into a shipbuilding city. The city quickly became the most crowded in the United States, and tensions rose as workers, white and black, fought over limited space and jobs. Between 1940 and 1943, 89,000 war workers descended on the city in an unprecedented expansion of Mobile’s population. By the end of the war, the population of Mobile County had increased by more than 60 percent. Mobile shipyards completed hundreds of ships for wartime service. In 1943, a race riot at the Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company occurred after company executives promoted 12 African Americans to the position of welder in response to Roosevelt’s executive order on fair employment. Brookley Field, established in 1941 as an air-supply depot and expanded after the United States entered the war, became the city’s largest postwar employer for two decades. The economic boom created by Brookley Field led to a sense of complacency among city leaders, who did not actively seek out new industry. The closure of the base in the 1960s contributed to Mobile’s stagnating economy for more than a decade.

Civil Rights

Downtown Mobile, 1954

Mobile was spared of the violent protests that characterized its northern neighbors Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma during the civil rights movement. In Mobile, two local grassroots organizations, the Non-Partisan Voters’ League and later the Neighborhood Organized Workers, exerted influence on city politics. The league initiated several important legal suits, including the desegregation suit for Mobile’s public schools—one of the longest-running cases of its kind. The league also sponsored the case Bolden v. Mobile, which held that the at-large election of representatives was inherently discriminatory to minorities. The suit resulted in the first female and African American commissioners in the city’s long history. In 2005, the city elected Samuel Jones as its first African American mayor.

Downtown Mobile, 1954

Mobile was spared of the violent protests that characterized its northern neighbors Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma during the civil rights movement. In Mobile, two local grassroots organizations, the Non-Partisan Voters’ League and later the Neighborhood Organized Workers, exerted influence on city politics. The league initiated several important legal suits, including the desegregation suit for Mobile’s public schools—one of the longest-running cases of its kind. The league also sponsored the case Bolden v. Mobile, which held that the at-large election of representatives was inherently discriminatory to minorities. The suit resulted in the first female and African American commissioners in the city’s long history. In 2005, the city elected Samuel Jones as its first African American mayor.

Civil Rights March in Mobile, 1968

Throughout the twentieth century, Mobile maintained a carefully cultivated aura of respectability in racial matters. During the height of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Mobile’s city leaders sponsored a biracial commission in an attempt to address inequalities in the area and avoid conflict. A similar commission was established in the 1960s at a time when protests in Birmingham and Selma were being met with violence. Neither body was very effective, but their existence helped to create a perception that Mobile had adopted a different approach to calls for black equality. Throughout the civil rights movement, leaders chose to portray Mobile as more respectable than other southern cities with regard to desegregation. Yet this image is oftentimes at odds with actual events, notably the lynching of Michael Donald in 1981 by local Klansmen—widely recognized as one of the last such acts of racial mob violence in America—and the city’s deeply segregated Mardi Gras festivities, which contain only a spattering of integrated activities.

Civil Rights March in Mobile, 1968

Throughout the twentieth century, Mobile maintained a carefully cultivated aura of respectability in racial matters. During the height of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Mobile’s city leaders sponsored a biracial commission in an attempt to address inequalities in the area and avoid conflict. A similar commission was established in the 1960s at a time when protests in Birmingham and Selma were being met with violence. Neither body was very effective, but their existence helped to create a perception that Mobile had adopted a different approach to calls for black equality. Throughout the civil rights movement, leaders chose to portray Mobile as more respectable than other southern cities with regard to desegregation. Yet this image is oftentimes at odds with actual events, notably the lynching of Michael Donald in 1981 by local Klansmen—widely recognized as one of the last such acts of racial mob violence in America—and the city’s deeply segregated Mardi Gras festivities, which contain only a spattering of integrated activities.

In recent years, large industrial developments have characterized the area around Mobile, including the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway and natural gas platforms along the coast. In 2010, German steel manufacturer Thyssen-Krupp opened a large facility just north of the city; now owned by AM/NS Calvert, it employs some 1,500 people. Several large hospitals in Mobile serve the region of south Alabama and the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Demographics

According to 2020 Census estimates, Mobile recorded a population of 189,994. Of that number, 51.1 percent identified themselves as African American, 43.6 percent as white, 2.5 percent as two or more races, 1.8 percent as Asian, 2.7 percent as Hispanic, and 0.3 percent as American Indian. The city’s median household income was $43,456, and per capita income was $28,810.

Employment

The workforce in Mobile, according to 2020 Census estimates, was divided among the following industrial categories:

- Educational services, and health care and social assistance (25.0 percent)

- Arts, entertainment, recreation, and accommodation and food services (11.7 percent)

- Retail trade (11.5 percent)

- Professional, scientific, management, and administrative and waste management services (11.0 percent)

- Manufacturing (9.9 percent)

- Finance, insurance, and real estate, rental, and leasing (5.6 percent)

- Transportation and warehousing and utilities (5.5 percent)

- Construction (5.3 percent)

- Public administration (4.7 percent)

- Other services, except public administration (4.6 percent)

- Wholesale trade (2.6 percent)

- Information (1.8 percent)

- Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and extractive (0.7 percent)

Education

Mobile is served by several institutions of higher education. The city is home to Spring Hill College, one of the oldest colleges in the South; the University of Mobile, a Baptist-affiliated school; the University of South Alabama; and Bishop State Community College. Numerous public, private and parochial schools serve the elementary and secondary educational needs of the city.

Events and Places of Interest

Bellingrath Holiday Lights

Mobile has a deep history of cultural rituals, which include the Azalea Trail, hosting America’s Junior Miss Pageant, and, of course, Mardi Gras. The city is home to the USS Alabama and Battleship Park, Bellingrath Gardens and Home, Mobile Botanical Gardens, the Gulf Coast Exploreum, the Mobile Museum of Art, the William and Emily Hearin Mobile Carnival Museum, and the award-winning History Museum of Mobile. For 300 years, the city of Mobile has been at the forefront of the cultural, economic, and political history of the Gulf Coast. Mobile continues to be dependent upon the port facility for the majority of its economic prosperity. The city is one of the most culturally diverse in the South. Mobile has more than 150 historic buildings and historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places presenting a wide variety of notable architectural and other structures, ranging from Government Street Presbyterian Church (1837) to the USS Drum submarine. The Duffie Oak, considered to be the city’s oldest living landmark, is a 300-year-old live oak located on Caroline Street in the city’s Historic District. The tree is 48 feet high with a circumference of 128 feet. It has been recognized as a historic landmark by the Alabama Forestry Commission and the National Arborist Association.

Bellingrath Holiday Lights

Mobile has a deep history of cultural rituals, which include the Azalea Trail, hosting America’s Junior Miss Pageant, and, of course, Mardi Gras. The city is home to the USS Alabama and Battleship Park, Bellingrath Gardens and Home, Mobile Botanical Gardens, the Gulf Coast Exploreum, the Mobile Museum of Art, the William and Emily Hearin Mobile Carnival Museum, and the award-winning History Museum of Mobile. For 300 years, the city of Mobile has been at the forefront of the cultural, economic, and political history of the Gulf Coast. Mobile continues to be dependent upon the port facility for the majority of its economic prosperity. The city is one of the most culturally diverse in the South. Mobile has more than 150 historic buildings and historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places presenting a wide variety of notable architectural and other structures, ranging from Government Street Presbyterian Church (1837) to the USS Drum submarine. The Duffie Oak, considered to be the city’s oldest living landmark, is a 300-year-old live oak located on Caroline Street in the city’s Historic District. The tree is 48 feet high with a circumference of 128 feet. It has been recognized as a historic landmark by the Alabama Forestry Commission and the National Arborist Association.

Further Reading

- Amos [Doss], Harriet E. Cotton City: Urban Development in Antebellum Mobile. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

- Bergeron, Arthur W. Confederate Mobile. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991.

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Urban Emancipation: Popular Politics in Reconstruction Mobile, 1860-1890. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002.

- Higganbotham, Jay. Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702-1711. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991.

- Kirkland, Scotty E. “Pink Sheets and Black Ballots: Politics and Civil Rights in Mobile, Alabama, 1945-1985.” Master’s thesis, University of South Alabama, 2009.

- Pride, Richard. The Political Use of Racial Narratives: School Desegregation in Mobile, Alabama, 1954-1997. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- Thomason, Michael V. R., ed. Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

External Links

- City of Mobile

- Mobile Public Library

- Visit Mobile

- Encycylopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

- History Museum of Mobile

- Mobile Museum of Art

- Mobile Carnival Museum

- Richards-DAR House Museum

- GulfQuest: National Maritime Museum of the Gulf of Mexico

- USS Alabama Battleship Memorial

- Mobile Medical Museum

- Saenger Theatre

- Southern Literary Trail

- Mobile Civic Center

- Mobile Theatre Guild

- National Register of Historic Places: Mobile County

- Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center

- Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

- University of South Alabama

- Spring Hill College

- Bishop State Community College

- University of Mobile

- Mobile BayBears

- Mobile National Cemetery