Plantation Architecture in Alabama

Perhaps no aspect of early American architecture is more charged with emotional symbolism—or more misunderstood—than the architecture of the plantation. Its legendary centerpiece, the white-columned mansion, suggests oppression to some and a romanticized lost way of life to others. It is an image that was first fueled by nostalgic post-Civil War southerners and then later enshrined in Hollywood movies and popular fiction. But in Alabama, as in the rest of the South, the architectural reality was substantially more complex.

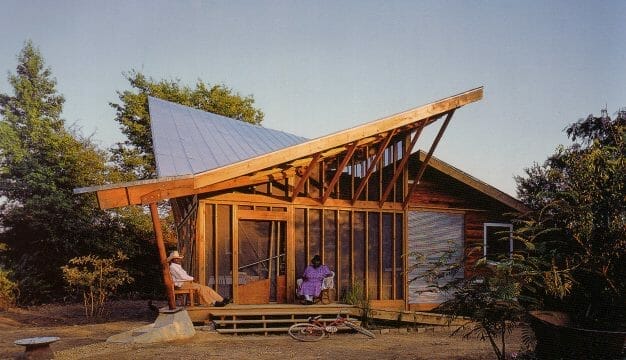

Alpine Plantation, Talladega County

To pre-Civil War Americans, and southerners in particular, the word “plantation” had a specific meaning: namely, a large farm producing a cash crop—cotton, tobacco, rice, or sugarcane—with enslaved African American labor. In what is now Alabama, early French colonists had established a few primitive plantations in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta by the mid-eighteenth century. But no architectural vestige of these remains today. Rather, it was Anglo-American settlers pushing west from Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia soon after 1800 who introduced the plantation landscape and architecture that would come to dominate Alabama’s richest cotton-growing areas prior to the Civil War.

Alpine Plantation, Talladega County

To pre-Civil War Americans, and southerners in particular, the word “plantation” had a specific meaning: namely, a large farm producing a cash crop—cotton, tobacco, rice, or sugarcane—with enslaved African American labor. In what is now Alabama, early French colonists had established a few primitive plantations in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta by the mid-eighteenth century. But no architectural vestige of these remains today. Rather, it was Anglo-American settlers pushing west from Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia soon after 1800 who introduced the plantation landscape and architecture that would come to dominate Alabama’s richest cotton-growing areas prior to the Civil War.

Although developing first around Huntsville in the fertile central Tennessee Valley, Alabama’s plantation landscape eventually came to center on the dark-soiled Black Belt, which stretches in an erratic crescent across the south-central part of the state from Mississippi nearly to the Georgia line. As cotton production soared in the 1840s and 1850s to feed the burgeoning textile mills of the Northeast and Europe, significant plantation enclaves also developed along the Coosa, the Tallapoosa, and the lower Chattahoochee rivers, as well as in the broad Appalachian valleys around Talladega, Oxford, and Jacksonville. Only a fraction of Alabama’s farms could ever be classified as true plantations in terms of scale, productivity, and architecture. Yet the image and idealized vision of the plantation still exercises a powerful influence on the historical imagination of the state.

The Plantation Setting and Complex

The nerve center of the Alabama plantation was a group of buildings strategically arranged to support the production and processing of cotton and to house those who produced it: the owner, the manager or “overseer” (if the plantation was a large one), and of course the African American slaves whose labor underpinned the plantation economy. No Alabama plantation complex survives intact today. But a few remain complete enough to suggest the ways in which the various buildings related to each other. These include Preuit Oaks and Johnson’s Woods, both in Colbert County; Thornhill in Greene County; Spring Hill, also known as the John Fletcher Comer plantation, in Barbour County; Orange Vale in Talladega County; the Lewis Alexander plantation in Macon County, and the Webb plantation (despite the loss of the main residence) in Perry County.

In terms of both layout and the unpretentious scale of its buildings, Preuit Oaks near Leighton in the Tennessee Valley, conveys an authentic sense of the typical Alabama plantation. Between level fields, a long tree-lined lane approaches the main house: a white-painted story-and-a-half dwelling dating from 1847 with green shutters and fronted by a simple gabled portico. To one side stands a small plantation “office,” where estate records were kept and business transacted. To the rear is an informal scattering of outbuildings, barns, and other necessary structures. And at a greater distance still are two cemeteries: one for the plantation owner’s family and another for the slaves. The overall character is clearly that of a working farm rather than a baronial estate. Yet in 1860, Preuit Oaks was the center of a 2,500-acre plantation with more than 200 enslaved workers, placing the owner among the top 10 percent of all Alabama slaveowners. Yet as a “middle-of-the-road” plantation architecturally, Preuit Oaks reinforces the contention of many historians that planters generally tended to reinvest agricultural profits in land and labor rather than in grandiose architectural improvements.

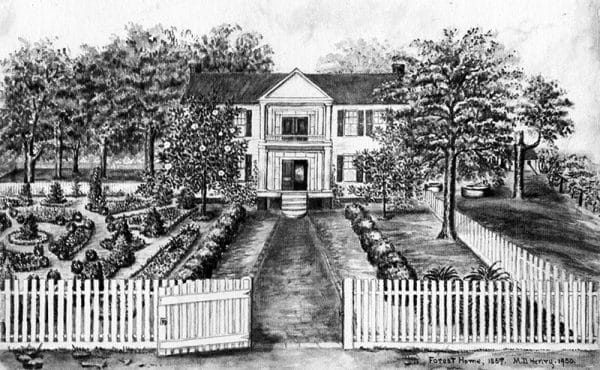

Artist’s Rendering of Forest Home Plantation

The typical plantation layout also included vegetable gardens, cornfields, pastures, and chicken coops, hog pens, and other livestock shelters. Some plantations also boasted an ornamental garden, usually enclosed by a paling fence to keep out stray animals. Garden designs themselves might range from winding, boxwood-bordered paths that occasionally centered on a summerhouse or gazebo, to more homely patterns of simple raised flowerbeds. Chantilly and Rose Hill near Montgomery, Rosemount near Forkland, and the aptly named Flower Hill near Courtland were renowned for their cultivated grounds. Scant evidence of such plantation horticulture survives today, and little research has been done on the topic in Alabama.

Artist’s Rendering of Forest Home Plantation

The typical plantation layout also included vegetable gardens, cornfields, pastures, and chicken coops, hog pens, and other livestock shelters. Some plantations also boasted an ornamental garden, usually enclosed by a paling fence to keep out stray animals. Garden designs themselves might range from winding, boxwood-bordered paths that occasionally centered on a summerhouse or gazebo, to more homely patterns of simple raised flowerbeds. Chantilly and Rose Hill near Montgomery, Rosemount near Forkland, and the aptly named Flower Hill near Courtland were renowned for their cultivated grounds. Scant evidence of such plantation horticulture survives today, and little research has been done on the topic in Alabama.

The Plantation “Big House”

To the slaves living on an Alabama plantation, the main residence was simply “the big house”—a term connoting not so much the physical size of the house as the power and authority it represented. Indeed, Alabama plantation houses varied widely in appearance, refinement, and scale and were in themselves no sure indicator of their occupants’ wealth or social status.

Some planters clearly felt more need for architectural display than others. Conversely, some of the state’s wealthiest planters and slaveowners, such as John Peters of Lauderdale County (who owned more than 300 slaves) and Thomas Johnston of Greensboro (who owned close to 500)—lived in relative modesty. In about 1850, when historian Albert James Pickett visited Sen. Nicholas Davis at his prosperous Walnut Grove plantation in Limestone County, he found Davis—who owned more than 100 slaves—still ensconced in the “large old log house” he had built after first coming from Virginia in 1817. Davis assured Pickett that it was a residence he “would not exchange for a palace.”

In fact, colorful plantation names such as Altwood, Hill of Howth, Bentwood Park, Pond Spring, and Bermuda Hill often belied the fact that the plantation houses itself was nothing more than an “improved” (the popular term of the time) log dwelling. It may have started out as a one or two-story “dogtrot” (open center hall) house that was later covered with wood siding, sash windows, and perhaps a decorative front door. With walls plastered inside and embellished with chairrails, decorative mantelpieces, and perhaps even an attractive stairway, such dwellings physically expressed the transition from frontier to settled rural community.

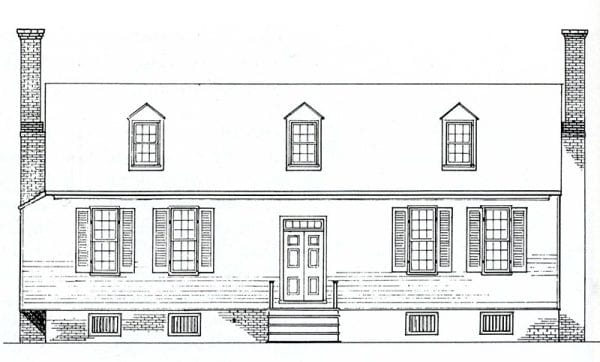

Bride’s Hill, Lawrence County

Most notably during the earliest decades of settlement—the 1820s and 1830s—Alabama planters and their architect/builders often built houses, large and small, recalling the architecture of the older states from which they came. Thus, Bride’s Hill (now called Sunnybrook) in Lawrence County, with its dormer windows and end chimneys, was essentially a stylistic transplant from Tidewater Virginia. The high basements of Umbria, Hale County, and Boligee Hill (now Myrtle Hall) in Greene County, evoked the “raised cottage” plantation houses of piedmont and low-country South Carolina. On the other hand, Sweetwater and Woodlawn in Lauderdale County, Col. Fleming Jordan’s plantation house in Madison County, and Weyanoke in Marengo County all retained the formal air of similar but earlier Georgian and Federal-style residences along the Atlantic coast, especially from the Chesapeake Bay southward. At the same time, the white neoclassical porticoes and red-brick walls of Belle Mont (Colbert County) and Saunders Hall (Lawrence County) owed much to the distinctive Palladian-derived architecture of Jeffersonian Virginia, from which their owners had come to Alabama.

Bride’s Hill, Lawrence County

Most notably during the earliest decades of settlement—the 1820s and 1830s—Alabama planters and their architect/builders often built houses, large and small, recalling the architecture of the older states from which they came. Thus, Bride’s Hill (now called Sunnybrook) in Lawrence County, with its dormer windows and end chimneys, was essentially a stylistic transplant from Tidewater Virginia. The high basements of Umbria, Hale County, and Boligee Hill (now Myrtle Hall) in Greene County, evoked the “raised cottage” plantation houses of piedmont and low-country South Carolina. On the other hand, Sweetwater and Woodlawn in Lauderdale County, Col. Fleming Jordan’s plantation house in Madison County, and Weyanoke in Marengo County all retained the formal air of similar but earlier Georgian and Federal-style residences along the Atlantic coast, especially from the Chesapeake Bay southward. At the same time, the white neoclassical porticoes and red-brick walls of Belle Mont (Colbert County) and Saunders Hall (Lawrence County) owed much to the distinctive Palladian-derived architecture of Jeffersonian Virginia, from which their owners had come to Alabama.

Moss Hill (Seale Plantation House), Wilcox County

One of the most widespread architectural imports from the Atlantic coast, for both town and plantation dwellings, was what is now known as the “I” house. With a main block two stories high and only one room deep, the house takes its odd name from the resulting tall, slender side profile. One particularly striking I-house variant—now sometimes known romantically as the “plantation-plain style”—featured a long, one-story porch across the front, with a corresponding shed-roofed extension across the rear. Thus, upstairs rooms had ventilation on three sides, a distinct advantage in a hot climate. Sometimes a simple, classically proportioned one- or two-story portico lent formality to the façade of the I-style plantation house. And now and then there was a full double veranda, as at Oak Manor in Sumter County, which also features a rooftop observatory.

Moss Hill (Seale Plantation House), Wilcox County

One of the most widespread architectural imports from the Atlantic coast, for both town and plantation dwellings, was what is now known as the “I” house. With a main block two stories high and only one room deep, the house takes its odd name from the resulting tall, slender side profile. One particularly striking I-house variant—now sometimes known romantically as the “plantation-plain style”—featured a long, one-story porch across the front, with a corresponding shed-roofed extension across the rear. Thus, upstairs rooms had ventilation on three sides, a distinct advantage in a hot climate. Sometimes a simple, classically proportioned one- or two-story portico lent formality to the façade of the I-style plantation house. And now and then there was a full double veranda, as at Oak Manor in Sumter County, which also features a rooftop observatory.

Rosemount, Greene County

Regarding the stately pillared houses of popular legend, Alabama plantation culture produced some very notable examples, although they were certainly the exception. Belle Mina (1826), Saunders Hall (circa 1830), and the column-encircled Forks of Cypress (1820s), all in the Tennessee Valley, were among the earliest of the stereotypical pillared plantation houses. Later examples include Thornhill and Rosemount in Greene County, both of which are older houses that acquired classical colonnades around 1845-50; Glennville Plantation (1840s) in Russell County; Youpon (circa 1840) in Wilcox County; Belvoir (probably early 1850s) in Dallas County; the Barton Stone plantation house (1852) in Montgomery County; and Mount Ida in Talladega County, where a massive colonnade was grafted on to what had formerly been a modest I-house just before the Civil War.

Rosemount, Greene County

Regarding the stately pillared houses of popular legend, Alabama plantation culture produced some very notable examples, although they were certainly the exception. Belle Mina (1826), Saunders Hall (circa 1830), and the column-encircled Forks of Cypress (1820s), all in the Tennessee Valley, were among the earliest of the stereotypical pillared plantation houses. Later examples include Thornhill and Rosemount in Greene County, both of which are older houses that acquired classical colonnades around 1845-50; Glennville Plantation (1840s) in Russell County; Youpon (circa 1840) in Wilcox County; Belvoir (probably early 1850s) in Dallas County; the Barton Stone plantation house (1852) in Montgomery County; and Mount Ida in Talladega County, where a massive colonnade was grafted on to what had formerly been a modest I-house just before the Civil War.

Glennville Plantation Interior

Despite their outward differences, the interior layouts of most plantation houses—whether of one or two stories or of frame or of brick—tended toward a marked similarity. Typically, the plan centered on a broad, high-ceilinged hallway with wide doors at each end, a welcome ventilating device during a sultry Alabama summer. Usually there were no more than one or two rooms to either side. In more formal houses, these were linked by large sliding (“pocket”) or folding doors that could be thrown open to create one large entertaining space. Occasionally an elegant stair graced a plantation house, such as the spiral stairways at Glennville, Belle Mina, and Thornhill, or the soaring double stair at Barton Hall. More common, especially after 1850, were ornate plaster cornices and ceiling centerpieces, and favored decorative treatments for wood trim throughout the antebellum period in plantation houses of all descriptions were “grained” or “marbleized” paint finishes applied by traveling artists in patterns that imitated mahogany, marble, and other expensive materials.

Glennville Plantation Interior

Despite their outward differences, the interior layouts of most plantation houses—whether of one or two stories or of frame or of brick—tended toward a marked similarity. Typically, the plan centered on a broad, high-ceilinged hallway with wide doors at each end, a welcome ventilating device during a sultry Alabama summer. Usually there were no more than one or two rooms to either side. In more formal houses, these were linked by large sliding (“pocket”) or folding doors that could be thrown open to create one large entertaining space. Occasionally an elegant stair graced a plantation house, such as the spiral stairways at Glennville, Belle Mina, and Thornhill, or the soaring double stair at Barton Hall. More common, especially after 1850, were ornate plaster cornices and ceiling centerpieces, and favored decorative treatments for wood trim throughout the antebellum period in plantation houses of all descriptions were “grained” or “marbleized” paint finishes applied by traveling artists in patterns that imitated mahogany, marble, and other expensive materials.

The workaday life of most plantation houses usually centered around a rear “gallery” or porch, where routine chores might be performed. Invariably, at least until after the Civil War, cooking was done in a separate kitchen building that in some instances sheltered a dining room as well. Basement levels might also have cooking and dining facilities, as at Bride’s Hill (Lawrence County) and Myrtle Hall (Greene County).

Hawthorn

The rising cotton prosperity of the late 1840s and 1850s resulted in a flurry of plantation house construction, particularly across south-central Alabama. Especially popular there was the single-story, hipped-roof plantation house fronted either by a full-length veranda or a smaller neoclassical central portico. Yet increasingly after 1850, plantation houses reflected newer trends in domestic architecture, including the Italianate and Gothic Revival styles. Thus Waldwick at Gallion is a rambling cottage in the Gothic style, whereas nearby Hawthorn, with its tall, wide-eaved tower, attempts to evoke the spirit of a rural Italian villa, despite its very American wood siding. Similarly, Rocky Hill (1857) combined a mansion in the Italianate style with a free-standing six-story Gothic tower.

Hawthorn

The rising cotton prosperity of the late 1840s and 1850s resulted in a flurry of plantation house construction, particularly across south-central Alabama. Especially popular there was the single-story, hipped-roof plantation house fronted either by a full-length veranda or a smaller neoclassical central portico. Yet increasingly after 1850, plantation houses reflected newer trends in domestic architecture, including the Italianate and Gothic Revival styles. Thus Waldwick at Gallion is a rambling cottage in the Gothic style, whereas nearby Hawthorn, with its tall, wide-eaved tower, attempts to evoke the spirit of a rural Italian villa, despite its very American wood siding. Similarly, Rocky Hill (1857) combined a mansion in the Italianate style with a free-standing six-story Gothic tower.

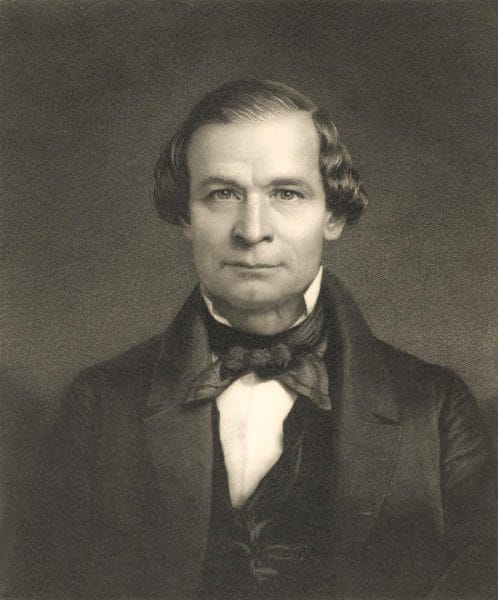

Nathan Bryan Whitfield

In 1858, Edward Kenworthy Carlisle engaged the New York architectural firm of Richard Upjohn to design his sophisticated plantation mansion near Marion—a house that rivaled the Italianate style villas of the Hudson Valley. Gaineswood, usually regarded as Alabama’s most lavish plantation house, evolved between 1842 and 1861 from a two-story log house into a unique and nationally significant expression of Greek Revival design. In this instance, Gaineswood’s owner, General Nathan Bryan Whitfield, was his own architect and was planning still more improvements when the Civil War interrupted further work. In most cases, however, local craftsmen, including enslaved artisans such as Peter Lee of Marengo County and two slaves remembered simply as “Lev” and “Grif” in Calhoun County, were responsible for erecting the plantation “big house.”

Nathan Bryan Whitfield

In 1858, Edward Kenworthy Carlisle engaged the New York architectural firm of Richard Upjohn to design his sophisticated plantation mansion near Marion—a house that rivaled the Italianate style villas of the Hudson Valley. Gaineswood, usually regarded as Alabama’s most lavish plantation house, evolved between 1842 and 1861 from a two-story log house into a unique and nationally significant expression of Greek Revival design. In this instance, Gaineswood’s owner, General Nathan Bryan Whitfield, was his own architect and was planning still more improvements when the Civil War interrupted further work. In most cases, however, local craftsmen, including enslaved artisans such as Peter Lee of Marengo County and two slaves remembered simply as “Lev” and “Grif” in Calhoun County, were responsible for erecting the plantation “big house.”

Plantation houses continued to be built sporadically in Alabama even after the Civil War, but they were hardly comparable in scale to the finest of their antebellum predecessors. Extant examples are Hedge Hill (circa 1870) in Marengo County and the Queen Anne-style McQueen Smith plantation house (circa 1900) in Autauga County.

Outbuildings and Slave Quarters

Plantation Office at Thorn Hill

Although the assemblage of outbuildings varied from plantation to plantation, depending on the needs and the whims of the owner, a core group of predictable structures inevitably clustered about the big house: the separate kitchen or “cook house,” the smokehouse, at least one well (often covered by a shelter and sometimes supplemented by an underground brick cistern connected by a pipe to a rooftop catchment for rainwater), privies, animal pens, corn cribs, stables, and barns. In addition, there were cotton storage and gin houses, sometimes the plantation office (as at Preuit Oaks and Thorn Hill), and of course the slave quarters. Often there was a plantation blacksmith shop, and on occasion a dovecote or pigeon house. The ensemble of outbuildings at the Robert Tait plantation in Wilcox County included a laundry or “ironing house,” and records suggest a few plantations with their own modest chapel. Federal Historic American Building Survey records for Alabama, available online from the Library of Congress, depict examples of many of these.

Plantation Office at Thorn Hill

Although the assemblage of outbuildings varied from plantation to plantation, depending on the needs and the whims of the owner, a core group of predictable structures inevitably clustered about the big house: the separate kitchen or “cook house,” the smokehouse, at least one well (often covered by a shelter and sometimes supplemented by an underground brick cistern connected by a pipe to a rooftop catchment for rainwater), privies, animal pens, corn cribs, stables, and barns. In addition, there were cotton storage and gin houses, sometimes the plantation office (as at Preuit Oaks and Thorn Hill), and of course the slave quarters. Often there was a plantation blacksmith shop, and on occasion a dovecote or pigeon house. The ensemble of outbuildings at the Robert Tait plantation in Wilcox County included a laundry or “ironing house,” and records suggest a few plantations with their own modest chapel. Federal Historic American Building Survey records for Alabama, available online from the Library of Congress, depict examples of many of these.

Brick Kitchen at Borders Plantation

Typically, the separate plantation kitchen stood directly behind or to the side of the main residence—often linked to the dining room of the “big house” by a covered walkway. Sometimes a one-room frame or log building, served by a massive chimney at one end, sufficed for the kitchen. Often just as common throughout the Alabama plantation country was the two-room kitchen: a pair of side-by-side rooms served by a single, large central chimney. One room served as the true kitchen, and the other often served as living quarters for the cook. Fear of fire sometimes dictated that the kitchen be built of brick even when the main house was itself of frame construction. Next to the kitchen might stand a tall, pyramid-roofed frame smokehouse and even a log corncrib. Practicality rather than aesthetics governed the design of these structures.

Brick Kitchen at Borders Plantation

Typically, the separate plantation kitchen stood directly behind or to the side of the main residence—often linked to the dining room of the “big house” by a covered walkway. Sometimes a one-room frame or log building, served by a massive chimney at one end, sufficed for the kitchen. Often just as common throughout the Alabama plantation country was the two-room kitchen: a pair of side-by-side rooms served by a single, large central chimney. One room served as the true kitchen, and the other often served as living quarters for the cook. Fear of fire sometimes dictated that the kitchen be built of brick even when the main house was itself of frame construction. Next to the kitchen might stand a tall, pyramid-roofed frame smokehouse and even a log corncrib. Practicality rather than aesthetics governed the design of these structures.

At Thorn Hill and Rosemount in Greene County and Umbria near Greensboro, small plantation schoolhouses served the children of the owner’s household and sometimes those from neighboring farms and plantations as well. At Roseland near Faunsdale, medicines were dispensed to the plantation laborers from a small columned “apothecary” building. Although the main house is gone, Roseland also preserves a rare surviving plantation “cooler,” or spring house.

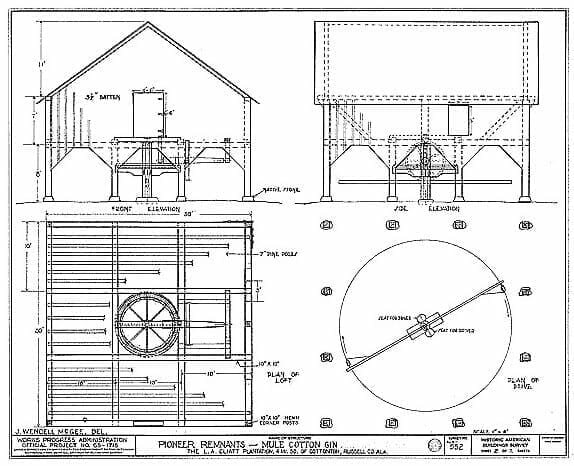

Gin House Diagram, Cliatt Plantation

Gin houses and cotton storage sheds were a critical feature of the plantation landscape, with most larger estates having their own gin and storage facilities. Here mule-driven, or in some cases steam-powered, machinery separated the cotton seed from the fibers, known as lint, after which it was stored until compressed by a giant wooden screw into bales for shipment to markets in Mobile and other major cities. Today, the Comer plantation at Spring Hill preserves one of Alabama’s few remaining plantation gin houses.

Gin House Diagram, Cliatt Plantation

Gin houses and cotton storage sheds were a critical feature of the plantation landscape, with most larger estates having their own gin and storage facilities. Here mule-driven, or in some cases steam-powered, machinery separated the cotton seed from the fibers, known as lint, after which it was stored until compressed by a giant wooden screw into bales for shipment to markets in Mobile and other major cities. Today, the Comer plantation at Spring Hill preserves one of Alabama’s few remaining plantation gin houses.

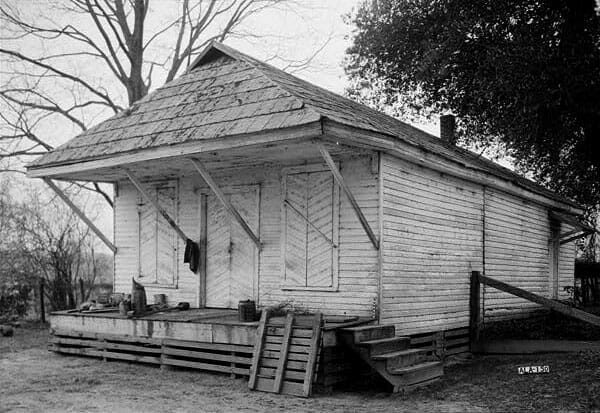

Plantation Commissary at Rosemary

Though some antebellum plantations had a “commissary” from which food and supplies were distributed to the slaves, the plantation store—which continued to be called a commissary—was essentially a post-war addition to the plantation architectural landscape in Alabama. Here tenants and sharecroppers purchased, on credit against the next cotton crop, the staples for their everyday existence.

Plantation Commissary at Rosemary

Though some antebellum plantations had a “commissary” from which food and supplies were distributed to the slaves, the plantation store—which continued to be called a commissary—was essentially a post-war addition to the plantation architectural landscape in Alabama. Here tenants and sharecroppers purchased, on credit against the next cotton crop, the staples for their everyday existence.

Sharecropper’s Home in Dallas County

It is ironic that even vestiges of worker housing—once the most common and distinctive architectural feature of Alabama’s plantation landscape—have all but disappeared. In part, this is because so many were insubstantial to begin with. Slave quarters, especially for the field hands, were of the most rudimentary construction: rough log or frame cabins with batten shutters in lieu of glass for the windows. Earthen floors were not uncommon, and, in the earliest days particularly, chimneys might be crudely built of mud-covered logs and sticks. Slave houses usually stood in a closely spaced row or two ranged along the edge of the fields. If household domestics often enjoyed more comfortable lodgings near the big house,

Sharecropper’s Home in Dallas County

It is ironic that even vestiges of worker housing—once the most common and distinctive architectural feature of Alabama’s plantation landscape—have all but disappeared. In part, this is because so many were insubstantial to begin with. Slave quarters, especially for the field hands, were of the most rudimentary construction: rough log or frame cabins with batten shutters in lieu of glass for the windows. Earthen floors were not uncommon, and, in the earliest days particularly, chimneys might be crudely built of mud-covered logs and sticks. Slave houses usually stood in a closely spaced row or two ranged along the edge of the fields. If household domestics often enjoyed more comfortable lodgings near the big house,

Dogtrot Cabin at Belle Mont Plantation

the few remaining examples suggest a Spartan existence for them as well. At Waldwick plantation in Marengo County, the steeply pitched roofs covering the dwellings of the household servants mimic the architecture of the main house while providing commodious attic space. But such attention to detail proved rare in this architecture of human bondage. After the Civil War, with the advent of tenancy and the sharecropping system, rows of worker housing often gave way to dwellings scattered irregularly over the plantation, as sharecroppers opted to work their own small parcels. Such sharecropper housing was a common sight in rural Alabama as late as the 1960s.

Dogtrot Cabin at Belle Mont Plantation

the few remaining examples suggest a Spartan existence for them as well. At Waldwick plantation in Marengo County, the steeply pitched roofs covering the dwellings of the household servants mimic the architecture of the main house while providing commodious attic space. But such attention to detail proved rare in this architecture of human bondage. After the Civil War, with the advent of tenancy and the sharecropping system, rows of worker housing often gave way to dwellings scattered irregularly over the plantation, as sharecroppers opted to work their own small parcels. Such sharecropper housing was a common sight in rural Alabama as late as the 1960s.

Some former plantation houses now open to the public include Gaineswood on the outskirts of Demopolis, Belle Mont near Tuscumbia, Pond Spring (the General Joseph Wheeler Plantation) near Courtland (all three owned by the Alabama Historical Commission), Buena Vista near Prattville (owned by the Autauga County Heritage Association), and the Sadler plantation house near Bessemer (owned by the West Jefferson Historical Society).

Conclusion

Civil war and the abrupt cessation of slavery altered but did not erase this landscape. Slavery turned into tenancy and many of the old relationships between owners and workers continued. Yet gone were the comfortable profits that had sustained an expanding if exploitative economic system and built the columned houses of popular imagination. Eclipsed and challenged by the state’s nascent industrialization and growing economic diversification, the planter way of life—if not its aristocratic mystique—slowly waned.

Outbuildings at Crenshaw Plantation

Yet significant architectural vestiges lingered on into the 1930s, when the newly created Historic American Buildings Survey recorded, through numerous photographs and measured drawings, a sampling of the architecture of Alabama’s plantation country: its dilapidated “big houses,” crumbling slave quarters, and tenant shacks; its outbuildings, fencerows, commissaries, and gin houses. Since World War II, even these vestiges have all but disappeared. Today, surviving traces of plantation architecture must be searched out: a few well-maintained old mansions, now and then a rare slave house, numberless abandoned farm buildings, or a huddle of weatherbeaten marble gravestones marking the site of a forgotten plantation cemetery.

Outbuildings at Crenshaw Plantation

Yet significant architectural vestiges lingered on into the 1930s, when the newly created Historic American Buildings Survey recorded, through numerous photographs and measured drawings, a sampling of the architecture of Alabama’s plantation country: its dilapidated “big houses,” crumbling slave quarters, and tenant shacks; its outbuildings, fencerows, commissaries, and gin houses. Since World War II, even these vestiges have all but disappeared. Today, surviving traces of plantation architecture must be searched out: a few well-maintained old mansions, now and then a rare slave house, numberless abandoned farm buildings, or a huddle of weatherbeaten marble gravestones marking the site of a forgotten plantation cemetery.

Additional Resources

Burkhardt, E. Walter, and Varian Burkhardt. Alabama Ante-bellum Architecture: A Scrapbook View from the 1930s. Montgomery: Alabama Historical Commission,1976.

Cooper, Chip, Harry Knopke, and Robert Gamble. Silent in the Land. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: CKM Press, 1993.

Gamble, Robert. The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey. A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State, 1810-1930. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.

———. “Landmark Loss and Renewal: Update and Retrospective on the April 2011 Storms.” Alabama Heritage 104 (Spring 2012): 36-43.

Vlach, John. Back of the Big House: The Cultural Landscape of the Plantation House. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Waselkov, Gregory A., et al. Plantation Archaeology at Riviere aux Chiens, ca. 1725-1848. Mobile: University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies, 2000.