Lurleen B. Wallace (1967-68)

Lurleen Wallace Official Portrait

Lurleen Burns Wallace (1926-1968) died from cancer a mere 16 months after taking office as governor of Alabama. Although she had clearly been elected as a stand-in for her husband, George Wallace, Alabamians genuinely mourned the loss of not only the first woman to be elected to the position but also someone with whom many of the state’s average citizens could relate. Never a politician, Wallace ran for governor in 1966 to facilitate her husband’s run for president in 1968, and like her husband, she defiantly denounced federal court-ordered desegregation. Her administration is not remembered for any particular legislation. Rather, she succeeded in drawing attention to the twin issues of mental and public health by focusing on the state’s widely criticized treatment of the mentally ill and the need for more state parks and recreational facilities.

Lurleen Wallace Official Portrait

Lurleen Burns Wallace (1926-1968) died from cancer a mere 16 months after taking office as governor of Alabama. Although she had clearly been elected as a stand-in for her husband, George Wallace, Alabamians genuinely mourned the loss of not only the first woman to be elected to the position but also someone with whom many of the state’s average citizens could relate. Never a politician, Wallace ran for governor in 1966 to facilitate her husband’s run for president in 1968, and like her husband, she defiantly denounced federal court-ordered desegregation. Her administration is not remembered for any particular legislation. Rather, she succeeded in drawing attention to the twin issues of mental and public health by focusing on the state’s widely criticized treatment of the mentally ill and the need for more state parks and recreational facilities.

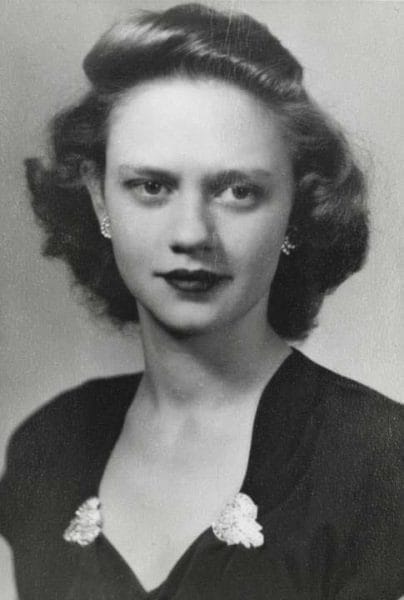

Young Lurleen Wallace

Born into a working-class family on September 19, 1926, Lurleen Burns descended from early Tuscaloosa County settlers. The family occasionally raised crops on their land, but Lurleen’s father, Henry Morgan Burns, worked mostly as a bargeman in Northport on the Black Warrior River and later as a crane operator in wartime Mobile. Her mother, Janie Estelle Burroughs, managed the household. Lurleen often went fishing her father and older brother Cecil and developed a lifelong passion for the hobby. After graduating from Tuscaloosa County High School in 1942, the attractive, green-eyed, and slightly built teenager began working as a sales clerk in a local dime store, where she soon met George Wallace. Having just graduated from the University of Alabama‘s law school and awaiting induction into the armed services, the 24-year-old George began to court the 16-year-old Lurleen. He left for basic training but returned to Tuscaloosa to recuperate from meningitis. The pair married on May 21, 1943, while he was on furlough,.

Young Lurleen Wallace

Born into a working-class family on September 19, 1926, Lurleen Burns descended from early Tuscaloosa County settlers. The family occasionally raised crops on their land, but Lurleen’s father, Henry Morgan Burns, worked mostly as a bargeman in Northport on the Black Warrior River and later as a crane operator in wartime Mobile. Her mother, Janie Estelle Burroughs, managed the household. Lurleen often went fishing her father and older brother Cecil and developed a lifelong passion for the hobby. After graduating from Tuscaloosa County High School in 1942, the attractive, green-eyed, and slightly built teenager began working as a sales clerk in a local dime store, where she soon met George Wallace. Having just graduated from the University of Alabama‘s law school and awaiting induction into the armed services, the 24-year-old George began to court the 16-year-old Lurleen. He left for basic training but returned to Tuscaloosa to recuperate from meningitis. The pair married on May 21, 1943, while he was on furlough,.

Lurleen Wallace and Turkey

For two years, the Wallaces moved frequently around western air bases as his unit participated in the firebombing of Japan during World War II. After the war and their return to Alabama, Lurleen supported George’s run for the state legislature from Barbour County. She became the sole breadwinner of the family and although too young to vote herself, wrote campaign letters that he signed. After two terms in the legislature, George won election as state circuit judge for the Third Judicial District. The position provided enough income to allow the Wallaces to purchase a home in Clayton for their growing family. The job of raising the children—Bobbi Jo, born in 1945, Peggy Sue, born in 1950, George Junior, born in 1951, and Janie Lee, born in 1961—fell to Lurleen as George became increasingly consumed by politics. She spent much of her time with close friends and confidants Mary Jo Ventress, a home economics teacher, and Catherine Steineker, a homemaker who later served as her personal secretary.

Lurleen Wallace and Turkey

For two years, the Wallaces moved frequently around western air bases as his unit participated in the firebombing of Japan during World War II. After the war and their return to Alabama, Lurleen supported George’s run for the state legislature from Barbour County. She became the sole breadwinner of the family and although too young to vote herself, wrote campaign letters that he signed. After two terms in the legislature, George won election as state circuit judge for the Third Judicial District. The position provided enough income to allow the Wallaces to purchase a home in Clayton for their growing family. The job of raising the children—Bobbi Jo, born in 1945, Peggy Sue, born in 1950, George Junior, born in 1951, and Janie Lee, born in 1961—fell to Lurleen as George became increasingly consumed by politics. She spent much of her time with close friends and confidants Mary Jo Ventress, a home economics teacher, and Catherine Steineker, a homemaker who later served as her personal secretary.

An able assistant, Lurleen joined George on the campaign trail during his first governor’s race in 1958 but remained shy of crowds. After his defeat in the election and the loss of his judicial position, George moved the family to Montgomery to begin working on his 1962 gubernatorial campaign. Suspicion of adultery led a long-suffering Lurleen to threaten him with divorce, an act that would have ruined his political career. He persuaded her to remain in the marriage, however. Upon George’s election as governor in 1962, Lurleen assumed the responsibilities of First Lady. Although she played the role, the reticent Lurleen disliked playing hostess and declined invitations to join social clubs. In public, the demure wife of the chief executive appeared smartly attired in dress suits. In private, she wore hunting pants, smoked cigarettes, and drank an occasional beer and abundant amounts of coffee.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

During his administration’s battle with the federal government over school desegregation, symbolized by the “stand in the schoolhouse door,” George Wallace recognized the national popularity of his position and entered the U.S. presidential race in 1964. He soon abandoned the effort, however, and began preparing for the 1968 race. Alabama’s 1901 Constitution prevented a governor from holding two consecutive terms, so Wallace was confronted with the potential loss of state perks that facilitated his political ambitions. He decided to run Lurleen for governor, position himself as “advisor,” and could continue his access to the public resources that subsidized his presidential campaigns. Lurleen had already been diagnosed with cancer and had undergone treatment, and many believed she agreed to run for governor out of misguided loyalty and at her own peril.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

During his administration’s battle with the federal government over school desegregation, symbolized by the “stand in the schoolhouse door,” George Wallace recognized the national popularity of his position and entered the U.S. presidential race in 1964. He soon abandoned the effort, however, and began preparing for the 1968 race. Alabama’s 1901 Constitution prevented a governor from holding two consecutive terms, so Wallace was confronted with the potential loss of state perks that facilitated his political ambitions. He decided to run Lurleen for governor, position himself as “advisor,” and could continue his access to the public resources that subsidized his presidential campaigns. Lurleen had already been diagnosed with cancer and had undergone treatment, and many believed she agreed to run for governor out of misguided loyalty and at her own peril.

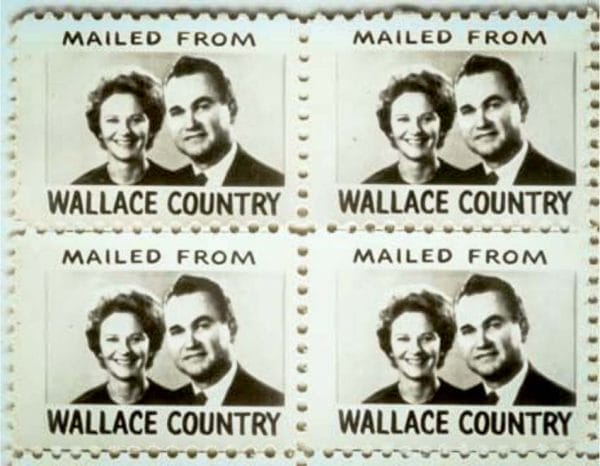

Lurleen Wallace Campaign Stamps

Early in her 1966 campaign, Lurleen Wallace said a few carefully prepared remarks before introducing her husband, who then lectured the crowd on federal abuses. After gaining confidence in her speaking abilities, Lurleen began speaking off the cuff, giving whole talks in George’s absence. She became a candidate in her own right, taking note of important people, shaking hands with voters, and making promises. In an almost unprecedented demonstration of popularity, Lurleen Wallace won the Democratic primary without a runoff. She defeated nine male opponents, including former governors James E. Folsom Sr. and John M. Patterson, Congressman Carl Elliott, and Attorney General Richmond Flowers. She easily defeated the Republican candidate, Congressman James D. Martin of Gadsden, in the November general election to become the first female governor of Alabama and only the third female governor in U.S. history to that time.

Lurleen Wallace Campaign Stamps

Early in her 1966 campaign, Lurleen Wallace said a few carefully prepared remarks before introducing her husband, who then lectured the crowd on federal abuses. After gaining confidence in her speaking abilities, Lurleen began speaking off the cuff, giving whole talks in George’s absence. She became a candidate in her own right, taking note of important people, shaking hands with voters, and making promises. In an almost unprecedented demonstration of popularity, Lurleen Wallace won the Democratic primary without a runoff. She defeated nine male opponents, including former governors James E. Folsom Sr. and John M. Patterson, Congressman Carl Elliott, and Attorney General Richmond Flowers. She easily defeated the Republican candidate, Congressman James D. Martin of Gadsden, in the November general election to become the first female governor of Alabama and only the third female governor in U.S. history to that time.

Lurleen Burns Wallace Inauguration

For the first five months of her administration, Wallace was healthy enough to actually govern the state. Yet many observed that her husband’s staff remained in the administration and that he made the decisions. George Wallace took an office across the hall from his wife, and the staff referred to them as Governor Lurleen and Governor George. Nevertheless, Lurleen Wallace brought to her governorship concerns that sometimes differed from those of her husband, and hers was not simply rule by proxy. Her first executive order directed the state treasurer to deposit state revenues only in banks that agreed to pay at least 2 percent interest on funds on deposit for more than 30 days. She continued the state’s fight against federal control of education and used legal tactics to resist guidelines for racial integration of schools issued by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. In a move of great importance to her spouse, the legislature finally passed and the people ratified an amendment to the 1901 Constitution allowing future governors to succeed themselves.

Lurleen Burns Wallace Inauguration

For the first five months of her administration, Wallace was healthy enough to actually govern the state. Yet many observed that her husband’s staff remained in the administration and that he made the decisions. George Wallace took an office across the hall from his wife, and the staff referred to them as Governor Lurleen and Governor George. Nevertheless, Lurleen Wallace brought to her governorship concerns that sometimes differed from those of her husband, and hers was not simply rule by proxy. Her first executive order directed the state treasurer to deposit state revenues only in banks that agreed to pay at least 2 percent interest on funds on deposit for more than 30 days. She continued the state’s fight against federal control of education and used legal tactics to resist guidelines for racial integration of schools issued by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. In a move of great importance to her spouse, the legislature finally passed and the people ratified an amendment to the 1901 Constitution allowing future governors to succeed themselves.

After touring Bryce and Partlow mental institutions in Tuscaloosa in February 1967, a visibly shaken governor recommended more spending to renovate the old hospital and school and increase the staff and number of beds. She enlisted the football coaches from Auburn University and the University of Alabama to lead a drive to raise funds to build a chapel for the facilities. After touring Kentucky’s new park system, the governor advocated improving Alabama’s natural and recreational facilities. She also endorsed reforms for care for the elderly. To fund these projects, she proposed a $43 million bond issue that the legislature passed in March and the voters approved in December.

Lake Lurleen

Public admiration and respect for Lurleen grew throughout her months as governor, as she brought to the office a charm that allayed most opposition and a bravery that enabled her to face her impending painful death. Doctors had first discovered evidence of cancer during the cesarean delivery of her fourth and last child, Janie Lee, in 1961. Although doctors informed George of the questionable tissue, they withheld the information from Lurleen and neglected to perform follow-up treatments. With the diagnosis of uterine cancer in November 1965, doctors prescribed six weeks of radiation treatments and then performed a hysterectomy. She recovered from what her husband’s administration called a “female operation” to run for office, but only five months into her term, the cancer returned. Her doctors in Montgomery recommended she seek treatment at the M. D. Anderson Clinic in Houston, Texas, where surgeons removed a tumor from her colon and began radiation treatments that caused cramps and nausea. In her long absences, a caretaker government managed affairs of state and George campaigned for president.

Lake Lurleen

Public admiration and respect for Lurleen grew throughout her months as governor, as she brought to the office a charm that allayed most opposition and a bravery that enabled her to face her impending painful death. Doctors had first discovered evidence of cancer during the cesarean delivery of her fourth and last child, Janie Lee, in 1961. Although doctors informed George of the questionable tissue, they withheld the information from Lurleen and neglected to perform follow-up treatments. With the diagnosis of uterine cancer in November 1965, doctors prescribed six weeks of radiation treatments and then performed a hysterectomy. She recovered from what her husband’s administration called a “female operation” to run for office, but only five months into her term, the cancer returned. Her doctors in Montgomery recommended she seek treatment at the M. D. Anderson Clinic in Houston, Texas, where surgeons removed a tumor from her colon and began radiation treatments that caused cramps and nausea. In her long absences, a caretaker government managed affairs of state and George campaigned for president.

Forbidden from being out of the state for more than 20 days at a time, a frail Lurleen briefly appeared at her office. She preferred to visit the governor’s retreat in Gulf Shores. Mid-September found her back in Houston for seven more weeks of radiation. Despite her weakness and pain, she joined George in California in November 1967 as he succeeded in getting on the state’s ballot as an independent candidate for president. Lurleen spent Christmas in Montgomery, but in early January 1968 doctors recommended more radiation treatments after finding numerous tumors. In an attempt to relieve the excruciating pain, surgeons performed a colostomy in February, a surgery that left the already weakened woman bedridden. Throughout the spring of 1968, the governor underwent repeated operations at St. Margaret’s Hospital and received spiritual comfort from the minister of the St. James Methodist Church. On April 13, 1968, she returned to the governor’s mansion to die. The family restricted visits to close friends. She weighed less than 85 pounds. High school bands serenaded her with “Dixie” outside her window. Off campaigning in Arkansas and Texas for most of that spring, George returned just in time to say goodbye. Surrounded by her family, Lurleen died at the age of 41 on May 7, 1968.

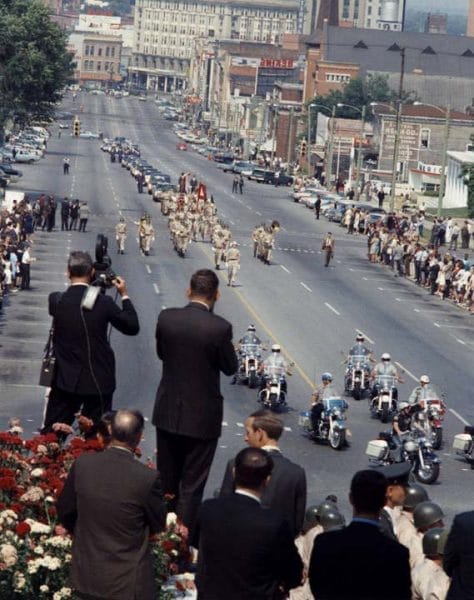

Funeral of Gov. Lurleen Wallace

The body of Lurleen Wallace lay in state in the capitol rotunda, and more than 30,000 Alabamians passed by in respect. George overrode Lurleen’s desires and, against her wishes to have a closed casket, ordered it open. The Poor People’s Campaign, assembled on the outskirts of Montgomery, cancelled its scheduled protest in the city, a sympathetic gesture to a woman who had remained an ardent foe of the civil rights movement and steadfast in her support of segregation. As governor, she struck a deep chord among many of the state’s citizens who admired her devotion to family, loyalty to an often unfaithful but charismatic husband, and unpretentious good nature. Lurleen Burns Wallace was not the most important governor of the state, but she may well have been its most loved.

Funeral of Gov. Lurleen Wallace

The body of Lurleen Wallace lay in state in the capitol rotunda, and more than 30,000 Alabamians passed by in respect. George overrode Lurleen’s desires and, against her wishes to have a closed casket, ordered it open. The Poor People’s Campaign, assembled on the outskirts of Montgomery, cancelled its scheduled protest in the city, a sympathetic gesture to a woman who had remained an ardent foe of the civil rights movement and steadfast in her support of segregation. As governor, she struck a deep chord among many of the state’s citizens who admired her devotion to family, loyalty to an often unfaithful but charismatic husband, and unpretentious good nature. Lurleen Burns Wallace was not the most important governor of the state, but she may well have been its most loved.

Further Reading

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, The Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- Frederick, Jeff. Stand Up For Alabama: Governor George Wallace. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

- Lesher, Stephen. George Wallace: American Populist. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1994.