Sharecropping and Tenant Farming in Alabama

Tenant Farmers Hoeing a Cotton Field

Sharecropping and tenant farming were the dominant economic model of Alabama agriculture from the late-nineteenth century through the onset of World War II. Both terms refer to forms of agriculture conducted by people who did not own the land they worked. These landless farmers worked the plots of other landowners. Although the system reached its zenith during the era of Reconstruction, tenancy existed in Alabama prior to the Civil War. Sharecropping, in particular, can be traced back to some of the earliest written records. The tenancy system, which by the early twentieth century encompassed more than 60 percent of the farming population in the state, left a legacy of poverty and illiteracy that began to be overcome only in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Tenant Farmers Hoeing a Cotton Field

Sharecropping and tenant farming were the dominant economic model of Alabama agriculture from the late-nineteenth century through the onset of World War II. Both terms refer to forms of agriculture conducted by people who did not own the land they worked. These landless farmers worked the plots of other landowners. Although the system reached its zenith during the era of Reconstruction, tenancy existed in Alabama prior to the Civil War. Sharecropping, in particular, can be traced back to some of the earliest written records. The tenancy system, which by the early twentieth century encompassed more than 60 percent of the farming population in the state, left a legacy of poverty and illiteracy that began to be overcome only in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

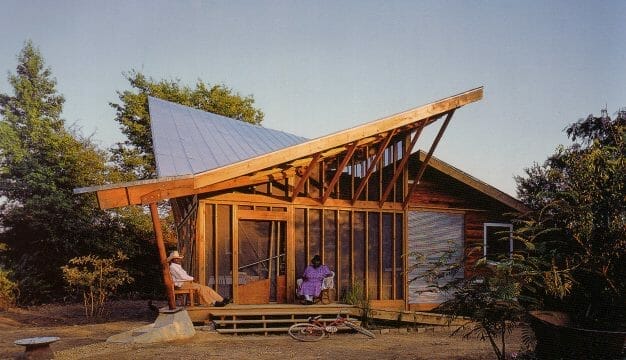

Dogtrot House in Montgomery County, 1944

Sharecropping and tenant farming, usually grouped together under “tenancy,” are not easy to define because the system that they describe was enormously complex. The terms encompass a wide variety of systems: At least seven varieties of tenancy were practiced in the United States; in Alabama, however, sharecropping and cash renting were the most common. Sharecropping involves landowners renting land to someone else in exchange for a portion of the crop, usually one-third to one-half, depending on what the sharecropper brought to the arrangement. Cash renting, as the name implies, refers to a rental agreement between farmers and landowners. Cash renters were generally of higher economic and social status than sharecroppers.

Dogtrot House in Montgomery County, 1944

Sharecropping and tenant farming, usually grouped together under “tenancy,” are not easy to define because the system that they describe was enormously complex. The terms encompass a wide variety of systems: At least seven varieties of tenancy were practiced in the United States; in Alabama, however, sharecropping and cash renting were the most common. Sharecropping involves landowners renting land to someone else in exchange for a portion of the crop, usually one-third to one-half, depending on what the sharecropper brought to the arrangement. Cash renting, as the name implies, refers to a rental agreement between farmers and landowners. Cash renters were generally of higher economic and social status than sharecroppers.

Antebellum Tenancy

Farm tenancy was important in Alabama agriculture for more than a century. U.S. Census and county records document tenant farmers in the Tennessee Valley of Alabama as early as 1850. The census of Lauderdale County, District One, of that year lists 667 farmers, of whom 53 were recorded as tenant farmers. The census from another district of Lauderdale County identifies several landless farmers as “cropper.” An observer in 1859 noted that two-thirds of all land in the cotton belt of Alabama was owned by a small portion of the population, a situation he feared would lead to widespread tenancy. Most of these tenants owned their own mules, equipment, and supplies, and some even owned slaves, but lacking land they turned to landowning relatives or neighbors. These tenant farmers were white and probably received one-half to two-thirds of the harvested cotton crop. Of course, slavery was the dominant labor source in the Cotton Belt until 1865, but antebellum tenancy certainly influenced the rise of sharecropping after the war.

Emancipation

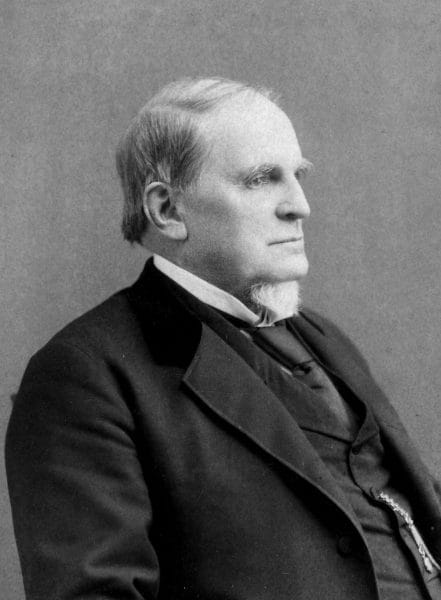

Lewis E. Parsons

In July 1865, slavery ended forever in Alabama when Gov. Lewis E. Parsons issued a proclamation declaring all slaves within the state free. Emancipation was given stronger legal standing in September 1865 when the Constitutional Convention in Montgomery adopted an ordinance abolishing slavery within Alabama. Now free to move about where they wished, many of the newly freed slaves left the plantations and farms and moved to urban centers, crowding into cities such as Huntsville, Selma, Montgomery, and Mobile. Rumors of land and equipment giveaways, popularly known as “40 acres and a mule,” were quickly revealed as false. Most freedpeople had to turn to charities and the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands (generally known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) for support, as did many destitute whites. Some people went in search of family members who had been sold during slavery. The black population of some cotton-producing areas, such as the Tennessee Valley, dropped by almost 10 percent, leaving fields uncultivated. As a result, land value depreciated and agricultural income became almost nonexistent. Alabama had been among the top 10 percent of the wealthiest states in the nation in 1860, a position it has never held since.

Lewis E. Parsons

In July 1865, slavery ended forever in Alabama when Gov. Lewis E. Parsons issued a proclamation declaring all slaves within the state free. Emancipation was given stronger legal standing in September 1865 when the Constitutional Convention in Montgomery adopted an ordinance abolishing slavery within Alabama. Now free to move about where they wished, many of the newly freed slaves left the plantations and farms and moved to urban centers, crowding into cities such as Huntsville, Selma, Montgomery, and Mobile. Rumors of land and equipment giveaways, popularly known as “40 acres and a mule,” were quickly revealed as false. Most freedpeople had to turn to charities and the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands (generally known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) for support, as did many destitute whites. Some people went in search of family members who had been sold during slavery. The black population of some cotton-producing areas, such as the Tennessee Valley, dropped by almost 10 percent, leaving fields uncultivated. As a result, land value depreciated and agricultural income became almost nonexistent. Alabama had been among the top 10 percent of the wealthiest states in the nation in 1860, a position it has never held since.

Landowners quickly realized that a new system of agricultural production had to be found. A variety of methods were suggested, including importing Chinese workers or white laborers from other areas of the nation and employing a wage-labor system. Most agriculturalists soon understood, however, that freedpeople were still the best source of labor. They were encouraged to return to the plantations as paid workers by the Freedmen’s Bureau, which, under the leadership of Gen. Wager Swayne, worked out contracts between Alabama freedpeople and landowners. The freedpeople were to live in the old slave quarters and work for cash in gangs as they had during slavery. The wage system, however, failed to work. Of the several reasons for the failure, the two most important were that the freedpeople refused to work in gangs or live in former slave quarters, and that landowners simply had no money to pay laborers.

It was obvious that two things had not changed as a result of the Civil War and emancipation. The first was that a majority of the agricultural riches were still in the hands of white landowners. The second was that former slaves would have to make up most of the post-war labor force and that freedpeople had nothing but their ability to work to bring to the contract. Thus a share-based agriculture was the key to restoring Alabama’s agricultural system. In this system, the cropper’s share of the crop depended on what he brought into the arrangement. If he provided only labor, he received one-third of the crop. If he were lucky enough to have draft animals, equipment, and supplies, he would receive half of the crop.

Tenant Farmer in Walker County

As early as the 1870s, most planters, newly freed slaves, and poor whites had accepted the sharecrop rental system as the answer to Alabama’s farm labor problem. It was a compromise, but it offered poor whites a means of eking out a meager existence; it gave freedpeople the semblance of the independence they craved; and it offered planters the opportunity to return plantations to productivity under some degree of personal supervision. Another element of the tenancy system was that economic domination by white landowners also helped maintain supremacy over blacks and poor whites. Although farm tenancy did not become an official category in the U.S. Census until 1880, several census takers in 1870 recorded tenant farmers.

Tenant Farmer in Walker County

As early as the 1870s, most planters, newly freed slaves, and poor whites had accepted the sharecrop rental system as the answer to Alabama’s farm labor problem. It was a compromise, but it offered poor whites a means of eking out a meager existence; it gave freedpeople the semblance of the independence they craved; and it offered planters the opportunity to return plantations to productivity under some degree of personal supervision. Another element of the tenancy system was that economic domination by white landowners also helped maintain supremacy over blacks and poor whites. Although farm tenancy did not become an official category in the U.S. Census until 1880, several census takers in 1870 recorded tenant farmers.

The post-Civil War tenancy system was designed for freedpeople, but it quickly encompassed a large number of poor whites; eventually white sharecroppers would outnumber blacks. After the Civil War, hill-country whites from north Alabama swarmed into Alabama’s Tennessee Valley to become tenant farmers. Between 1860 and 1866, the white population of the Tennessee Valley grew by more than 8 percent, as the black population declined. In the Wiregrass region of southeast Alabama, poor whites also dominated tenancy. Only in the Black Belt did freedpeople dominate tenant farming.

Life as a Tenant Farmer

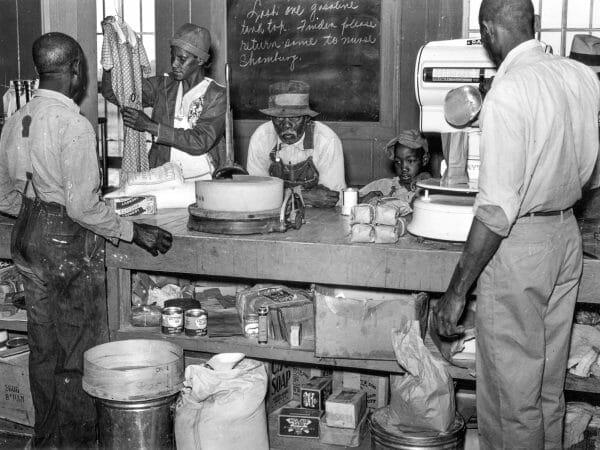

Gee’s Bend Cooperative Store

Landlords supplied sharecroppers with seed, fertilizer, plows, and draft animals. The tenant farmer also had to be supplied with the necessities of life: housing, fuel, food, snuff, and overalls, items collectively referred to as “furnishing.” Most tenants, especially sharecroppers, needed food and personal items advanced to them in order to manage until harvest time. Landlords usually had a small store or commissary to advance basic commodities, which they purchased on credit from merchants in towns. Landlords would take a mortgage on the unplanted crop (usually referred to as a “crop-lien”) as collateral.

Gee’s Bend Cooperative Store

Landlords supplied sharecroppers with seed, fertilizer, plows, and draft animals. The tenant farmer also had to be supplied with the necessities of life: housing, fuel, food, snuff, and overalls, items collectively referred to as “furnishing.” Most tenants, especially sharecroppers, needed food and personal items advanced to them in order to manage until harvest time. Landlords usually had a small store or commissary to advance basic commodities, which they purchased on credit from merchants in towns. Landlords would take a mortgage on the unplanted crop (usually referred to as a “crop-lien”) as collateral.

Very quickly, a new character entered the picture: the “furnishing merchant.” Landowners discovered that they could reduce their own indebtedness and diminish personal risk by allowing merchants in the towns and rural communities to furnish their tenants directly. Furnishing merchants protected their investments by taking a second crop-lien on a farmer’s crop. It has been estimated that as late as the early 1940s, the average sharecropper family’s income was less than 65 cents a day. Out of this meager income, farmers had to pay off advance indebtedness. If the crop did not bring enough to pay the entire debt, the remainder was added to the next year’s lien, a situation that one historian referred to as “debt peonage.” Generally, the interest rate for advanced goods was 10 percent. Added to that, the merchant often raised the price of goods sold on credit over and above that of items purchased with cash. Considering the higher mark-up and interest together, tenant farmers paid an interest rate that sometimes exceeded 50 percent annually.

Tenant Farming

The way of life of most tenant farmers was inferior to that of many people in medieval Europe. Housing consisted of primitive log cabins or clapboard shotgun houses. Few homes had glass windows or screens; most featured wooden shutters that could be closed at night and in inclement weather. Indoor plumbing was nonexistent; water was provided from open wells or nearby springs and creeks, and bathrooms were outdoor privies located a few yards behind the house, creating serious sanitation problems. Another problem facing tenant farmers was poor transportation. Until the 1950s, virtually all tenant farms were located on unimproved dirt roads. In 1930, of Alabama’s 257,395 farms, only 4,516 had access to hard-surface roads. Rain left unimproved roads impassable, and during dry weather, they were dusty, with deep ruts. As a result, tenants were generally isolated socially, and they faced economic ruin if the roads were unusable at harvest time.

Tenant Farming

The way of life of most tenant farmers was inferior to that of many people in medieval Europe. Housing consisted of primitive log cabins or clapboard shotgun houses. Few homes had glass windows or screens; most featured wooden shutters that could be closed at night and in inclement weather. Indoor plumbing was nonexistent; water was provided from open wells or nearby springs and creeks, and bathrooms were outdoor privies located a few yards behind the house, creating serious sanitation problems. Another problem facing tenant farmers was poor transportation. Until the 1950s, virtually all tenant farms were located on unimproved dirt roads. In 1930, of Alabama’s 257,395 farms, only 4,516 had access to hard-surface roads. Rain left unimproved roads impassable, and during dry weather, they were dusty, with deep ruts. As a result, tenants were generally isolated socially, and they faced economic ruin if the roads were unusable at harvest time.

The tenant family’s diet consisted mainly of cornbread, corn mush, fatback pork, and molasses. Some tenants were able to supplement their diet with vegetables if the landowner permitted use of a portion of their plot for a garden. Many landlords, however, wanted as much land in cotton as possible, so only a few farmers had gardens. Poor diet, lack of sanitation, and substandard housing led to widespread health concerns, such as hookworms, pellagra, and rickets.

Tenant Farming in the Twentieth Century

Plowing with Draft Animals in Pike County

By the 1890s, tenant farming dominated Alabama agriculture. Whether white or black, sharecroppers produced more cotton per acre than any other category of farmer. But more cotton did not translate into more money. The crop-lien system had a tight hold on Alabama tenant farmers, and families were lucky to break even at harvest each year. Many of those who did make money chose to buy their own draft animals and equipment and become cash renters. Some even became landowners, but the majority remained trapped in debt peonage.

Plowing with Draft Animals in Pike County

By the 1890s, tenant farming dominated Alabama agriculture. Whether white or black, sharecroppers produced more cotton per acre than any other category of farmer. But more cotton did not translate into more money. The crop-lien system had a tight hold on Alabama tenant farmers, and families were lucky to break even at harvest each year. Many of those who did make money chose to buy their own draft animals and equipment and become cash renters. Some even became landowners, but the majority remained trapped in debt peonage.

Tenant farmers faced another obstacle in the early twentieth century when the boll weevil, a cotton pest from Mexico, invaded the state. The boll weevil entered Texas from Mexico in the 1890s and by 1910 had reached southwest Alabama; by 1916, it had infested the entire state and devastated the cotton crop. In response to the economic losses, many farmers turned to other crops. In the Wiregrass region, peanuts came to dominate agricultural production. In 1917, Coffee County produced more peanuts than any other county in the United States. The Wiregrass is still known as the “Peanut Capital of the World.” In most of Alabama, however, cotton was still king and cotton production rose year after year until the Great Depression.

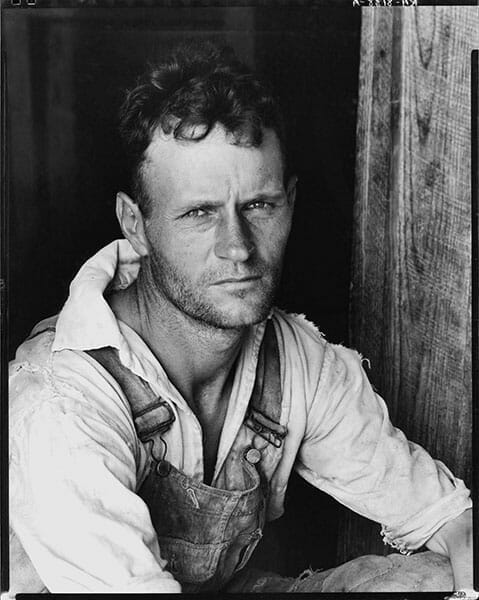

Tenant Farmer Floyd Burroughs

Likely as a result of the boll weevil and many other economic and social factors, including a desire to escape Jim Crow laws, blacks began to leave the South in large numbers in the early twentieth century. By 1915, hundreds of thousands of blacks were leaving the South for the North, in a movement known as the Great Migration. As a result, poor whites came to dominate the tenant system. Despite a drop in available labor, conditions did not improve for tenant farmers, and their plight came to national attention only through the efforts of novelists such as William Faulkner and works such as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a collaboration by author James Agee and photographer Walker Evans.

Tenant Farmer Floyd Burroughs

Likely as a result of the boll weevil and many other economic and social factors, including a desire to escape Jim Crow laws, blacks began to leave the South in large numbers in the early twentieth century. By 1915, hundreds of thousands of blacks were leaving the South for the North, in a movement known as the Great Migration. As a result, poor whites came to dominate the tenant system. Despite a drop in available labor, conditions did not improve for tenant farmers, and their plight came to national attention only through the efforts of novelists such as William Faulkner and works such as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a collaboration by author James Agee and photographer Walker Evans.

By the time of the Great Depression, tenant farming reached its peak in Alabama, encompassing well over 65 percent of all farmers, with sharecroppers making up 39 percent of this number. With the election of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the implementation of his New Deal programs, tenant farmers began to lose what little economic security that they had. Agencies such as the Agricultural Adjustment Administration actually drove tenants from the land by reducing the acreage planted and paying subsidies to landowners, all in an attempt to keep food prices higher; fewer acres meant less need for tenants to work the land. Many farmers found refuge in the projects of the Works Progress Administration, others sought work as day laborers, and some became dependent on public relief.

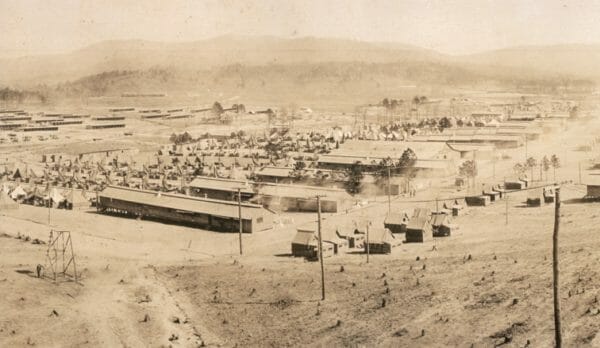

Camp McClellan, 1918

By 1940, tenants made up only about 56 percent of Alabama farmers, and the number of sharecroppers had dropped to 30 percent. In addition to the New Deal, the outbreak of World War II caused a decline. As war erupted in China in 1937 and in Europe in 1939, war industries began to evolve and thousands of American farm boys, white and black, left the farms for jobs in factories. As the United States was drawn into the war in 1941, hundreds of thousands of male tenant farmers were drafted into the military. Of those who survived the war, few returned to sharecroppers’ shacks. Many who did not go off to war found work in the military training camps and ordnance plants that sprang up across Alabama.

Camp McClellan, 1918

By 1940, tenants made up only about 56 percent of Alabama farmers, and the number of sharecroppers had dropped to 30 percent. In addition to the New Deal, the outbreak of World War II caused a decline. As war erupted in China in 1937 and in Europe in 1939, war industries began to evolve and thousands of American farm boys, white and black, left the farms for jobs in factories. As the United States was drawn into the war in 1941, hundreds of thousands of male tenant farmers were drafted into the military. Of those who survived the war, few returned to sharecroppers’ shacks. Many who did not go off to war found work in the military training camps and ordnance plants that sprang up across Alabama.

By 1954, tenancy had dropped to about 37 percent of all Alabama farmers, and sharecroppers made up only 27 percent of all tenants. The depression, World War II, and the rise of mechanization on farms after the war took their toll on tenant farmers. Scholars estimate that the use of tractors on farms in the cotton-producing states increased by 136 percent between 1940 and 1945. The U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Industrialization calculated that about 500,000 tractors were being used in the 13 cotton-producing states by 1945. The committee estimated that if such a trend continued, there would be 1,226,000 tractors by 1965. The other technological innovation in the cotton kingdom was the mechanical cotton picker, which was introduced into Alabama during the 1950s. One mechanical cotton picker could pick almost a thousand pounds more cotton per hour than the average human. By the early 1960s, almost 37 percent of Alabama’s cotton was picked by machines.

The Decline of Tenancy

There was no way for sharecroppers, tractors, and mechanical cotton pickers to live side by side, and thus sharecroppers slowly vanished from Alabama’s landscape. The 2002 Census of Agriculture lists a total of 62,572 farm operators in Alabama; of this number, 2,063 (3.3 percent) were classified as tenants, down from 3,151 in 1997. The Census makes no mention of sharecroppers. Sharecropping left an important if dubious legacy in the state. The system helped to keep Alabama behind other states, both economically and socially, far into the twentieth century. But the rise of mechanization and modern farming practices that helped end tenancy have today made Alabama among the most agriculturally important states in the nation.

Further Reading

- Fleming, Walter L. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. 1905. Reprint, New York: Peter Smith, 1949.

- Flynt, J. Wayne. Poor But Proud: Alabama’s Poor Whites. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1989.

- Kolchin, Peter. First Freedom: The Response of Alabama’s Blacks to Emancipation and Reconstruction. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972.

- Maharidge, Dale, and Michael Williamson. And Their Children After Them: The Legacy of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. New York: Pantheon Books, 1989.

- Phillips, Kenneth Edward. “Jubilee in the Fields: Alabama’s Landless Farmers in a Cotton Dominated Society.” Ph.D. diss., Auburn University, 1999.