Freedom Rides

Attack on Freedom Riders in Anniston

The 1961 Freedom Rides were public bus trips undertaken by racially integrated groups through the Deep South to test the enforcement of a newly enacted court order prohibiting segregation in interstate bus terminals. The riders were met with hostility and violence in a number of states, and they encountered some of the worst violence in Alabama. Civil authorities at the state and local levels actively refrained from protecting the participants from violent mobs, forcing the federal government to intervene. The nonviolent protests played a key role in publicizing the hostility facing the civil rights movement.

Attack on Freedom Riders in Anniston

The 1961 Freedom Rides were public bus trips undertaken by racially integrated groups through the Deep South to test the enforcement of a newly enacted court order prohibiting segregation in interstate bus terminals. The riders were met with hostility and violence in a number of states, and they encountered some of the worst violence in Alabama. Civil authorities at the state and local levels actively refrained from protecting the participants from violent mobs, forcing the federal government to intervene. The nonviolent protests played a key role in publicizing the hostility facing the civil rights movement.

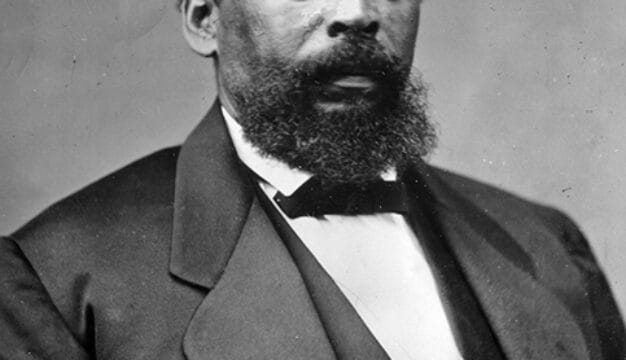

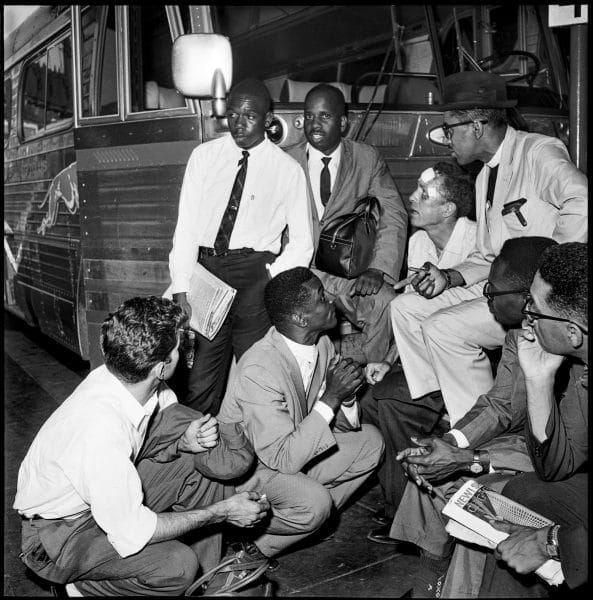

Freedom Riders in Birmingham

On May 4, 1961, two small groups, one of which included Alabama native and future U.S. congressman from Georgia John Lewis, embarked on a Greyhound and a Trailways bus from Washington, D.C., on the first leg of a trip to New Orleans, Louisiana. These trips were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and modeled on the organization’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, which had sought to test the effectiveness of desegregation laws in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia after the 1946 Morgan v. Virginia decision prohibited segregation on interstate buses.

Freedom Riders in Birmingham

On May 4, 1961, two small groups, one of which included Alabama native and future U.S. congressman from Georgia John Lewis, embarked on a Greyhound and a Trailways bus from Washington, D.C., on the first leg of a trip to New Orleans, Louisiana. These trips were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and modeled on the organization’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, which had sought to test the effectiveness of desegregation laws in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia after the 1946 Morgan v. Virginia decision prohibited segregation on interstate buses.

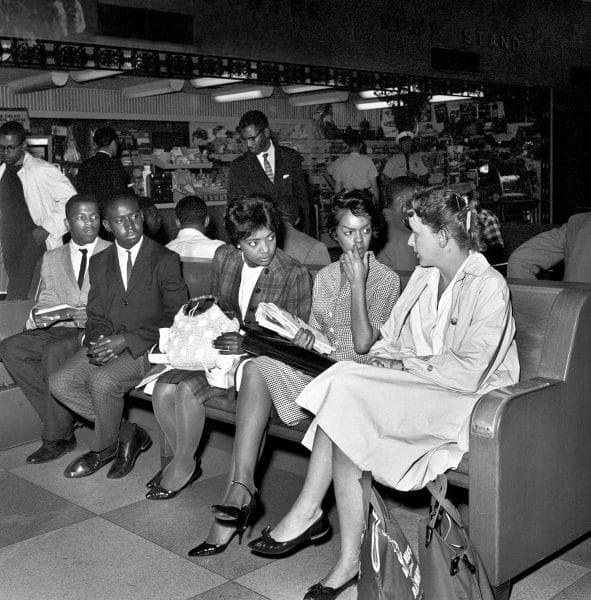

Paul Brooks and Jim Zwerg

The 1961 Freedom Rides, as CORE leaders called them, were guided by nonviolent principles and had a similar goal. They aimed to test the enforcement of the 1960 Supreme Court Bruce Boynton v. Virginia ruling that required desegregation of interstate bus seating and terminal facilities. The strategy was for black participants to sit up front and whites to sit in the back of the bus, with one pair of black and white participants seated together. Within the terminals, the riders planned to use segregated facilities such as restrooms and food services. CORE’s Freedom Riders met little resistance in the Upper South, but they encountered their first bloody scene when some minor violence erupted at the Rock Hill Greyhound Station in South Carolina, where Lewis was beaten by a group of young white men. The groups then stopped over in Atlanta, where they met with Martin Luther King Jr.

Paul Brooks and Jim Zwerg

The 1961 Freedom Rides, as CORE leaders called them, were guided by nonviolent principles and had a similar goal. They aimed to test the enforcement of the 1960 Supreme Court Bruce Boynton v. Virginia ruling that required desegregation of interstate bus seating and terminal facilities. The strategy was for black participants to sit up front and whites to sit in the back of the bus, with one pair of black and white participants seated together. Within the terminals, the riders planned to use segregated facilities such as restrooms and food services. CORE’s Freedom Riders met little resistance in the Upper South, but they encountered their first bloody scene when some minor violence erupted at the Rock Hill Greyhound Station in South Carolina, where Lewis was beaten by a group of young white men. The groups then stopped over in Atlanta, where they met with Martin Luther King Jr.

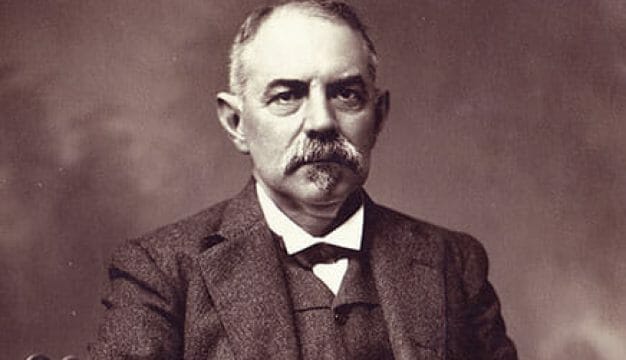

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

Forewarned by Birmingham civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth of possible attacks in Alabama, the groups pressed onward. On May 14, the Greyhound bus arrived at the terminal in Anniston, Calhoun County, where a white mob waited with clubs and bats. The crowd attacked the bus, breaking its windows and slashing tires, and then pursuing it until the driver was forced to stop because of flat tires several miles out of town. An attacker threw an incendiary bomb through a window, and the Freedom Riders and other passengers barely escaped the flames. E. L. Cowling, an Alabama undercover police officer, was aboard the bus and forced the attackers back at gunpoint. As the bus burned, the white mob beat the Freedom Riders until the police arrived and ended the violence. Shuttlesworth then sent an armed group from Birmingham to ferry the Greyhound riders from the Anniston hospital to a new bus. Shuttlesworth and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference also arranged housing and warned them of the likelihood of additional attacks, but the riders continued south, flying from Birmingham to New Orleans. A new group of riders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) carried on the Alabama leg of the ride from Birmingham to Montgomery and then on to Mississippi.

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

Forewarned by Birmingham civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth of possible attacks in Alabama, the groups pressed onward. On May 14, the Greyhound bus arrived at the terminal in Anniston, Calhoun County, where a white mob waited with clubs and bats. The crowd attacked the bus, breaking its windows and slashing tires, and then pursuing it until the driver was forced to stop because of flat tires several miles out of town. An attacker threw an incendiary bomb through a window, and the Freedom Riders and other passengers barely escaped the flames. E. L. Cowling, an Alabama undercover police officer, was aboard the bus and forced the attackers back at gunpoint. As the bus burned, the white mob beat the Freedom Riders until the police arrived and ended the violence. Shuttlesworth then sent an armed group from Birmingham to ferry the Greyhound riders from the Anniston hospital to a new bus. Shuttlesworth and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference also arranged housing and warned them of the likelihood of additional attacks, but the riders continued south, flying from Birmingham to New Orleans. A new group of riders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) carried on the Alabama leg of the ride from Birmingham to Montgomery and then on to Mississippi.

Greyhound Employees in Birmingham

The Trailways bus arrived in Anniston later that day and was met by a smaller mob. Still, a group of white men boarded the bus, knocked some of the activists to the floor when they protested the action, and viciously beat them. Walter Bergman, one of the white victims, suffered permanent brain damage. The Trailways bus next stopped at the Birmingham bus terminal, where it was met by a large crowd of whites—many belonging to the Ku Klux Klan—armed with pipes, chains, and baseball bats. Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, a vocal opponent of desegregation, had informed Klan leaders that the police would delay their arrival at the bus station for 15 minutes and encouraged the Klan to attack the riders. When the riders attempted to resume their journey, they were unable to find a bus driver who was willing to take them to Montgomery. CORE leaders chose to halt the ride, and the battered group, with the exception of John Lewis, flew to New Orleans to attend a May 17 rally to celebrate the seventh anniversary of the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

Greyhound Employees in Birmingham

The Trailways bus arrived in Anniston later that day and was met by a smaller mob. Still, a group of white men boarded the bus, knocked some of the activists to the floor when they protested the action, and viciously beat them. Walter Bergman, one of the white victims, suffered permanent brain damage. The Trailways bus next stopped at the Birmingham bus terminal, where it was met by a large crowd of whites—many belonging to the Ku Klux Klan—armed with pipes, chains, and baseball bats. Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, a vocal opponent of desegregation, had informed Klan leaders that the police would delay their arrival at the bus station for 15 minutes and encouraged the Klan to attack the riders. When the riders attempted to resume their journey, they were unable to find a bus driver who was willing to take them to Montgomery. CORE leaders chose to halt the ride, and the battered group, with the exception of John Lewis, flew to New Orleans to attend a May 17 rally to celebrate the seventh anniversary of the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

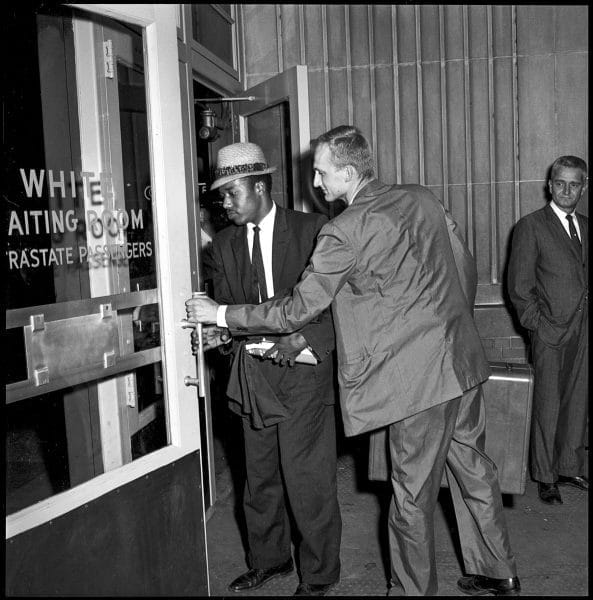

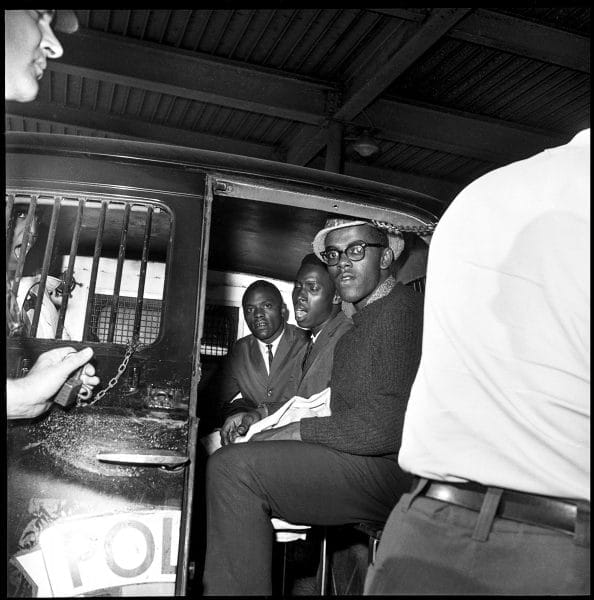

Freedom Riders Arrested in Birmingham

The widely publicized brutality against the Freedom Riders in Anniston and Birmingham encouraged the SNCC in Nashville to resume the rides. John Lewis and Diane Nash organized a group of eight blacks and two whites who left Nashville for Birmingham on May 17, 1961. As soon as they arrived in the Birmingham bus terminal, they were instantly arrested by police and held in what the police termed “protective custody.” That night, the participants, fearing for their lives, were driven to the Tennessee line by Bull Connor and the Birmingham police and dropped off in a predominantly white rural area known for Klan activity. They made their way back to Birmingham and on May 20 boarded a Greyhound bus to Montgomery, where they were again attacked by a crowd of whites. During the melee, Department of Justice official John Seigenthaler was beaten unconscious by the mob of Montgomery men and women. Alabama governor John Patterson‘s director of public safety, Floyd Mann, had arranged for safe passage from Birmingham to Montgomery, but Montgomery police failed to take over protection of the riders. Mann personally entered the melee to stop the attacks.

Freedom Riders Arrested in Birmingham

The widely publicized brutality against the Freedom Riders in Anniston and Birmingham encouraged the SNCC in Nashville to resume the rides. John Lewis and Diane Nash organized a group of eight blacks and two whites who left Nashville for Birmingham on May 17, 1961. As soon as they arrived in the Birmingham bus terminal, they were instantly arrested by police and held in what the police termed “protective custody.” That night, the participants, fearing for their lives, were driven to the Tennessee line by Bull Connor and the Birmingham police and dropped off in a predominantly white rural area known for Klan activity. They made their way back to Birmingham and on May 20 boarded a Greyhound bus to Montgomery, where they were again attacked by a crowd of whites. During the melee, Department of Justice official John Seigenthaler was beaten unconscious by the mob of Montgomery men and women. Alabama governor John Patterson‘s director of public safety, Floyd Mann, had arranged for safe passage from Birmingham to Montgomery, but Montgomery police failed to take over protection of the riders. Mann personally entered the melee to stop the attacks.

Throughout the rides and riots, Pres. John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, had sought assurances from Patterson that he would protect the riders, but to little avail. Indeed, Patterson famously blamed the civil rights activists for bringing the violence on themselves. The rash of attacks spurred the Kennedy administration to order federal marshals, led by future Supreme Court Justice Byron White, to enter Alabama to restore order.

Freedom Rides Museum Murals

On May 21, more than 1,000 black residents gathered at Ralph Abernathy’s First Baptist Church in Montgomery to honor the Freedom Riders. A mob surrounded the church and imprisoned the people, including Abernathy, King, and Shuttlesworth, assembled therein. After a long night, Patterson finally called up the National Guard, and Martin Luther King Jr. phoned the attorney general to negotiate safe passage to Jackson, Mississippi. On May 24, the Freedom Riders departed for Jackson with the National Guard as an escort. In Jackson, the police arrested the Freedom Riders, as well as several hundred protestors who had come out to support them. The prisoners were taken to maximum-security Parchman Penitentiary. Refusing to post bail, many remained in jail for 39 days, the limit they could serve and still make an appeal. The NAACP Legal and Defense Fund successfully appealed the convictions all the way up to the Supreme Court, which reversed them. Intending to pacify the situation, Justice Department officials convinced the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue a regulation prohibiting separate facilities for blacks and whites in bus and train terminals. The ruling was issued on September 22 and became effective on November 1, 1961, although defiance continued in many southern communities and rides continued throughout the summer.

Freedom Rides Museum Murals

On May 21, more than 1,000 black residents gathered at Ralph Abernathy’s First Baptist Church in Montgomery to honor the Freedom Riders. A mob surrounded the church and imprisoned the people, including Abernathy, King, and Shuttlesworth, assembled therein. After a long night, Patterson finally called up the National Guard, and Martin Luther King Jr. phoned the attorney general to negotiate safe passage to Jackson, Mississippi. On May 24, the Freedom Riders departed for Jackson with the National Guard as an escort. In Jackson, the police arrested the Freedom Riders, as well as several hundred protestors who had come out to support them. The prisoners were taken to maximum-security Parchman Penitentiary. Refusing to post bail, many remained in jail for 39 days, the limit they could serve and still make an appeal. The NAACP Legal and Defense Fund successfully appealed the convictions all the way up to the Supreme Court, which reversed them. Intending to pacify the situation, Justice Department officials convinced the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue a regulation prohibiting separate facilities for blacks and whites in bus and train terminals. The ruling was issued on September 22 and became effective on November 1, 1961, although defiance continued in many southern communities and rides continued throughout the summer.

In 2011, the Alabama Historical Commission opened the refurbished Greyhound bus station as the Freedom Rides Museum. In January 2017, Pres. Barack Obama designated the former station and the site where the bus was burned outside of Anniston as the Freedom Riders National Monument. They are part of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail and the Alabama Civil Rights Trail.

Further Reading

- Anderson, Dale. Freedom Rides: Campaign for Equality. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2007.

- Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Rides: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Eskew, Glenn T. But for Birmingham: The Local and the National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Niven, David. The Politics of Injustice: The Kennedys, the Freedom Rides, and the Electoral Consequences of a Moral Compromise. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003.

- Peck, James. Freedom Ride. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.