Joe Louis

Joe Louis

Known as the “Brown Bomber,” Alabama native Joe Louis (1914-1981) is considered one of the greatest heavyweight boxing champions of all time. At a time when most sports were still segregated in America, Louis was among the first African Americans to achieve national hero status in a white-dominated society. His defeat of German boxer Max Schmeling was renowned as a vivid refutation of Nazi Germany’s official policy of white superiority. He had a career record of 68 wins and 3 losses, with 54 wins by knockout. Louis still holds the record for successfully defending his title more times than any other heavyweight boxer, and his 27 championship bouts are also a record. In 1969, Joe Louis was inducted into the inaugural class of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

Joe Louis

Known as the “Brown Bomber,” Alabama native Joe Louis (1914-1981) is considered one of the greatest heavyweight boxing champions of all time. At a time when most sports were still segregated in America, Louis was among the first African Americans to achieve national hero status in a white-dominated society. His defeat of German boxer Max Schmeling was renowned as a vivid refutation of Nazi Germany’s official policy of white superiority. He had a career record of 68 wins and 3 losses, with 54 wins by knockout. Louis still holds the record for successfully defending his title more times than any other heavyweight boxer, and his 27 championship bouts are also a record. In 1969, Joe Louis was inducted into the inaugural class of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

Joseph Louis Barrow was born to Munroe and Lillie Barrow on May 13, 1914, in a shack at the foot of Buckalew Mountain near LaFayette in Chambers County. He became known simply as Joe Louis when he ran out of room for his last name when filling out a form for one of his first amateur fights. Louis’s father was a sharecropper; the circumstances of his life and death are somewhat unclear, but he was likely deceased early in Louis’s life. Louis’s mother took in washing to help support the family before marrying Patrick Brooks, joining her family of eight with his family of eight. In the summer of 1926, when Joe was 13, his newly expanded family moved to Detroit, where Brooks landed a job in the emerging automotive industry.

Marva Louis

School did not interest Louis, but he fell in love with boxing when a friend took him to a local gymnasium. When Louis turned 16, his mother began giving him money to pay for violin lessons, unaware that he was using the money instead to pay for a locker at the gym where he was learning to box. Although disappointed when she learned of his secret, his mother nevertheless encouraged him to pursue his talent as a boxer. Louis posted a 50-4 amateur record, making it to the Golden Gloves finals in 1933 and winning the National Amateur Athletic Union light heavyweight championship in 1934. His accomplishments attracted the attention of John Roxborough, a wealthy black Detroit businessman and gambling mogul. Roxborough brought in Julian Black, a Chicago nightclub owner and gambling manager, to help him manage Louis’s career when he turned professional in 1934. Roxborough would remain with Louis as his manager throughout his boxing career. In 1935, Louis married Marva Trotter (whom he divorced, remarried, and then divorced again in 1948), and the couple had two children, Jacqueline and Joe Louis Barrow Jr. Louis also adopted three other children.

Marva Louis

School did not interest Louis, but he fell in love with boxing when a friend took him to a local gymnasium. When Louis turned 16, his mother began giving him money to pay for violin lessons, unaware that he was using the money instead to pay for a locker at the gym where he was learning to box. Although disappointed when she learned of his secret, his mother nevertheless encouraged him to pursue his talent as a boxer. Louis posted a 50-4 amateur record, making it to the Golden Gloves finals in 1933 and winning the National Amateur Athletic Union light heavyweight championship in 1934. His accomplishments attracted the attention of John Roxborough, a wealthy black Detroit businessman and gambling mogul. Roxborough brought in Julian Black, a Chicago nightclub owner and gambling manager, to help him manage Louis’s career when he turned professional in 1934. Roxborough would remain with Louis as his manager throughout his boxing career. In 1935, Louis married Marva Trotter (whom he divorced, remarried, and then divorced again in 1948), and the couple had two children, Jacqueline and Joe Louis Barrow Jr. Louis also adopted three other children.

In the first fight of his professional career, Louis knocked out Chicago’s Jack Kracken on July 4, 1934, in a bout lasting less than two minutes. Louis thus exploded onto the professional scene, winning his first 27 fights, 23 by knockout, and amassing purses totaling $371,645, a staggering sum for the times. During this two-year period, he knocked out Primo Carnera, Kingfish Levinsky, Max Baer, and Paolino Uzcudum, all well-known heavyweights at the time, in a total of 12 rounds.

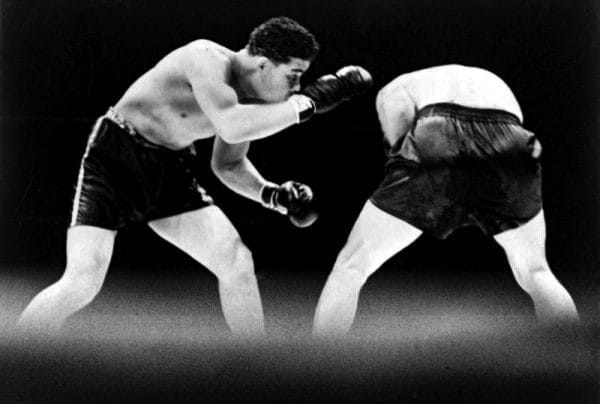

Joe Louis and Max Schmeling

Favored to win his much-anticipated match with German boxer Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936, Louis instead was handed his first defeat in the ring as a professional, with a knockout in round 12. Louis then defeated James Braddock on June 22, 1937, to capture the heavyweight title, but his defeat by Schmeling haunted him. Louis hoped to reverse the outcome when a rematch was scheduled for 1938. German Führer Adolf Hitler saw the rematch as an opportunity to prove his belief in white supremacy. Thus, Louis had much to motivate him in his preparation for one of the most significant sporting events in the twentieth century. In addition to his desire to avenge the only loss of his career and to dispel Hitler’s theory of racial superiority, Louis also carried the burden of representing all Americans in this event, which was rife with the political undercurrents of fascism versus democracy. On June 22, 1938, Louis knocked out Schmeling just two minutes and four seconds into the first round. With this resounding victory, Americans both white and black erupted into celebration. In African American communities, Louis immediately became a hero of unprecedented power and influence. Their idolization of Louis was reflected by the numerous poems published in black newspapers, songs composed to glorify his deeds, and the many portraits of him that hung in the homes of black Americans.

Joe Louis and Max Schmeling

Favored to win his much-anticipated match with German boxer Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936, Louis instead was handed his first defeat in the ring as a professional, with a knockout in round 12. Louis then defeated James Braddock on June 22, 1937, to capture the heavyweight title, but his defeat by Schmeling haunted him. Louis hoped to reverse the outcome when a rematch was scheduled for 1938. German Führer Adolf Hitler saw the rematch as an opportunity to prove his belief in white supremacy. Thus, Louis had much to motivate him in his preparation for one of the most significant sporting events in the twentieth century. In addition to his desire to avenge the only loss of his career and to dispel Hitler’s theory of racial superiority, Louis also carried the burden of representing all Americans in this event, which was rife with the political undercurrents of fascism versus democracy. On June 22, 1938, Louis knocked out Schmeling just two minutes and four seconds into the first round. With this resounding victory, Americans both white and black erupted into celebration. In African American communities, Louis immediately became a hero of unprecedented power and influence. Their idolization of Louis was reflected by the numerous poems published in black newspapers, songs composed to glorify his deeds, and the many portraits of him that hung in the homes of black Americans.

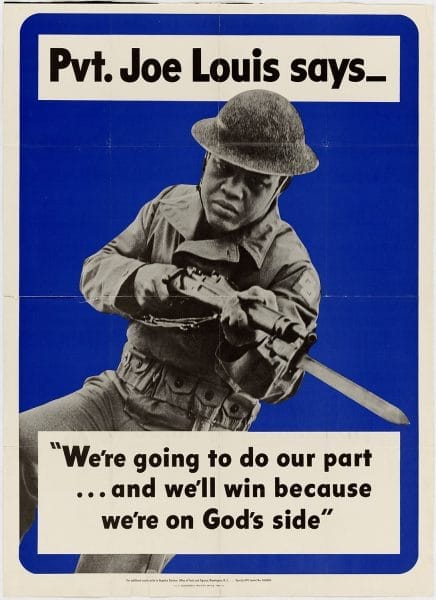

Joe Louis War Poster

Louis successfully defended his heavyweight title for 11 years in 24 matches, with 22 knockouts. As with many other professional athletes of the day, Louis’s boxing career was interrupted in 1942 when he enlisted in the Army after the United States had officially entered World War II the previous year. During his military service, Louis participated in 96 boxing exhibitions to raise money for Armed Services relief funds as well as to boost morale. Louis’s high profile also advanced the cause of desegregating the armed forces. Louis was able to use his status to help future baseball great Jackie Robinson and several other African American soldiers gain admittance to Officer Candidate School. After the war, Louis resumed his professional boxing career, successfully defending his title four more times before retiring on March 1, 1949. In 1951, Louis faced serious financial problems caused by his own generosity as well as by a huge bill for back taxes. Louis’s fights over the course of his career had grossed approximately $4.6 million, but he only actually received about $800,000 of it. As a result of his financial woes, Louis attempted a comeback, but his career ended when he was defeated by Rocky Marciano on October 26, 1951.

Joe Louis War Poster

Louis successfully defended his heavyweight title for 11 years in 24 matches, with 22 knockouts. As with many other professional athletes of the day, Louis’s boxing career was interrupted in 1942 when he enlisted in the Army after the United States had officially entered World War II the previous year. During his military service, Louis participated in 96 boxing exhibitions to raise money for Armed Services relief funds as well as to boost morale. Louis’s high profile also advanced the cause of desegregating the armed forces. Louis was able to use his status to help future baseball great Jackie Robinson and several other African American soldiers gain admittance to Officer Candidate School. After the war, Louis resumed his professional boxing career, successfully defending his title four more times before retiring on March 1, 1949. In 1951, Louis faced serious financial problems caused by his own generosity as well as by a huge bill for back taxes. Louis’s fights over the course of his career had grossed approximately $4.6 million, but he only actually received about $800,000 of it. As a result of his financial woes, Louis attempted a comeback, but his career ended when he was defeated by Rocky Marciano on October 26, 1951.

Joe Louis Statue in LaFayette

In his remaining years, Louis served as a celebrity greeter at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, appeared on quiz shows, and even tried professional wrestling. In 1955, he married Rose Morgan, a successful Harlem businesswoman; their marriage was annulled in 1958. In 1959, he married attorney Martha Jefferson. After the government agreed to forgive his tax debt, Louis was able to live a comfortable life. His health eventually deteriorated to the point that he was confined to a wheelchair. He suffered a stroke the year before his death and died of a heart attack on April 12, 1981, at the age of 66. Pres. Ronald Reagan waived the requirements for burial at the Arlington National Cemetery so that Joe Louis could be buried with full military honors. On February 27, 2010, Louis was honored by his hometown when an eight-foot bronze statue of the “Brown Bomber” was unveiled in LaFayette in front of a large crowd that included his son, Joe Louis Barrow Jr. The statue, sculpted by Casey Downing Jr., sits atop a base of Alabama red granite and is located near the Chambers County Courthouse.

Joe Louis Statue in LaFayette

In his remaining years, Louis served as a celebrity greeter at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, appeared on quiz shows, and even tried professional wrestling. In 1955, he married Rose Morgan, a successful Harlem businesswoman; their marriage was annulled in 1958. In 1959, he married attorney Martha Jefferson. After the government agreed to forgive his tax debt, Louis was able to live a comfortable life. His health eventually deteriorated to the point that he was confined to a wheelchair. He suffered a stroke the year before his death and died of a heart attack on April 12, 1981, at the age of 66. Pres. Ronald Reagan waived the requirements for burial at the Arlington National Cemetery so that Joe Louis could be buried with full military honors. On February 27, 2010, Louis was honored by his hometown when an eight-foot bronze statue of the “Brown Bomber” was unveiled in LaFayette in front of a large crowd that included his son, Joe Louis Barrow Jr. The statue, sculpted by Casey Downing Jr., sits atop a base of Alabama red granite and is located near the Chambers County Courthouse.

Further Reading

- Noles, James L., Jr. Hearts of Dixie: Fifty Alabamians and the State They Called Home. Birmingham, Ala.: Will Publishing, LLC, 2004.