Birmingham Iron and Steel Companies

Sipsey Mine Workers, 1913

Birmingham owes its 1871 founding to the geological uniqueness of the Jones Valley, the only place on Earth where large deposits of the three raw materials needed to make iron—coal (for conversion into coke), iron ore, and limestone—existed close together. Named for the industrial heart of Great Britain, the city prospered and grew as the iron, coal, and steel industry expanded. But labor issues, economic constraints imposed by northern owners, and eventual overseas competition hampered development, and Birmingham never evolved into the world-class steel-making center that its founders envisioned.

Sipsey Mine Workers, 1913

Birmingham owes its 1871 founding to the geological uniqueness of the Jones Valley, the only place on Earth where large deposits of the three raw materials needed to make iron—coal (for conversion into coke), iron ore, and limestone—existed close together. Named for the industrial heart of Great Britain, the city prospered and grew as the iron, coal, and steel industry expanded. But labor issues, economic constraints imposed by northern owners, and eventual overseas competition hampered development, and Birmingham never evolved into the world-class steel-making center that its founders envisioned.

In 1876, a small group of investors of the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company produced the first coke-fired iron at Oxmoor Furnace. Iron previously had been produced at the furnace with charcoal, which did not burn as efficiently or at as high a temperature and thus produced lower-quality iron. In 1880, several owners of the Pratt Coal and Coke Company, including Henry F. DeBardeleben, constructed Alice Furnace and produced its first iron. The initial success in producing iron for northern markets led the company to construct the larger Alice Furnace No. 2 (“Big Alice”), which began operations in 1883.

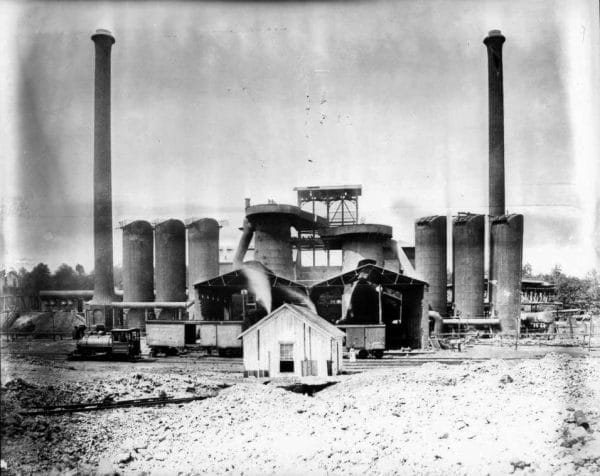

Eureka Furnace

The 1880s saw a frenzy of construction, in which 19 additional furnaces were erected in or near Birmingham. In 1881, Col. James W. Sloss founded the Sloss Furnace Company with two furnaces and became one of the city’s greatest promoters. The Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI), from the Sequatchie Valley near Chattanooga, Tennessee, constructed four furnaces and quickly became the largest enterprise in the Birmingham District, as the region encompassing the mineral deposits came to be known. The Woodward Iron Company, headed by a group of investors from West Virginia, and the Pioneer Mining and Manufacturing Company, whose owners came from Pennsylvania, built a number of furnaces. The DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company, an offshoot of Pratt, built four furnaces and an iron mill.

Eureka Furnace

The 1880s saw a frenzy of construction, in which 19 additional furnaces were erected in or near Birmingham. In 1881, Col. James W. Sloss founded the Sloss Furnace Company with two furnaces and became one of the city’s greatest promoters. The Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI), from the Sequatchie Valley near Chattanooga, Tennessee, constructed four furnaces and quickly became the largest enterprise in the Birmingham District, as the region encompassing the mineral deposits came to be known. The Woodward Iron Company, headed by a group of investors from West Virginia, and the Pioneer Mining and Manufacturing Company, whose owners came from Pennsylvania, built a number of furnaces. The DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company, an offshoot of Pratt, built four furnaces and an iron mill.

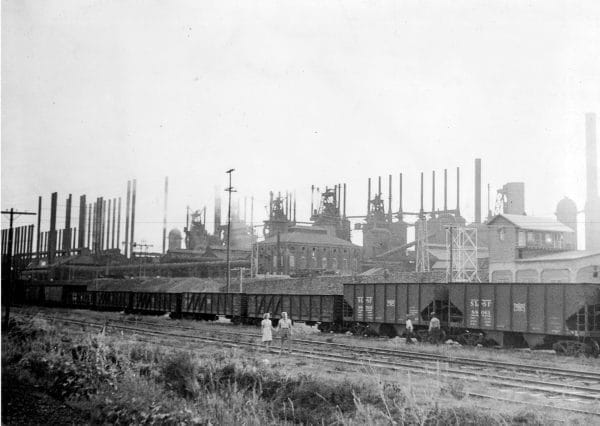

Woodward Iron Company

Each of these firms used a system known as “straight-line production,” in which all steps of the production process followed one upon the other in an assembly-line that took advantage of the proximity to the raw materials to reduce transportation costs. The companies marketed their products to Cincinnati, Louisville, and cities in the Northeast, where furnaces were fired by less-efficient anthracite coal and could not compete with lower-cost southern rivals. The companies kept labor costs low by employing black workers, who came from depressed agricultural areas and supplied cheap labor. And the coal used to fire the furnaces was largely mined by forced convict labor leased to the companies at very low rates by the state and county governments.

Woodward Iron Company

Each of these firms used a system known as “straight-line production,” in which all steps of the production process followed one upon the other in an assembly-line that took advantage of the proximity to the raw materials to reduce transportation costs. The companies marketed their products to Cincinnati, Louisville, and cities in the Northeast, where furnaces were fired by less-efficient anthracite coal and could not compete with lower-cost southern rivals. The companies kept labor costs low by employing black workers, who came from depressed agricultural areas and supplied cheap labor. And the coal used to fire the furnaces was largely mined by forced convict labor leased to the companies at very low rates by the state and county governments.

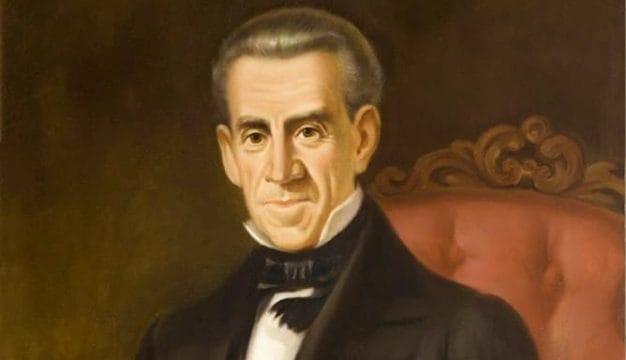

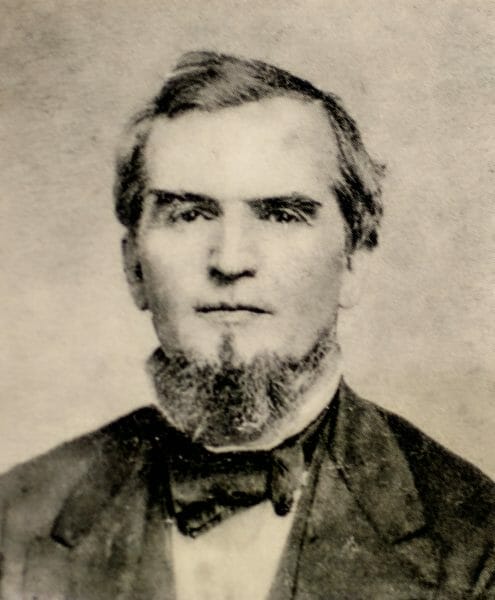

James W. Sloss

The Birmingham firms were all financially successful except for the Sloss Furnace Company. Colonel Sloss, hoping to lure outside investment to Birmingham’s steel industry, sold his interest in the firm for $2 million to investors, mostly from Virginia, who reorganized the firm as the Sloss Iron and Steel Company in 1886-87. The addition of the word steel to the new company’s name was significant. All of the existing companies in Birmingham produced “pig iron,” which was formed in molds laid out in a pattern resembling piglets nursing at the belly of a sow, hence the name. Pig iron has a very high carbon content and as a result is very brittle and difficult to work with and therefore has limited use in manufacturing. Steel is an alloy, or mixture, of iron and a small but crucial amount of carbon that (depending on the quality of the iron used) produces a highly workable metal that was more suitable for shaping into rails for the expanding railroad industry. Birmingham’s local iron ore was high in phosphorus, which produced inferior steel. Sloss hoped to employ a new steelmaking process capable of eliminating phosphorus, but its patents were owned by Pennsylvania industrialist Andrew Carnegie and his Carnegie Steel Company. Thus, Sloss could not use them to manufacture the coveted alloy.

James W. Sloss

The Birmingham firms were all financially successful except for the Sloss Furnace Company. Colonel Sloss, hoping to lure outside investment to Birmingham’s steel industry, sold his interest in the firm for $2 million to investors, mostly from Virginia, who reorganized the firm as the Sloss Iron and Steel Company in 1886-87. The addition of the word steel to the new company’s name was significant. All of the existing companies in Birmingham produced “pig iron,” which was formed in molds laid out in a pattern resembling piglets nursing at the belly of a sow, hence the name. Pig iron has a very high carbon content and as a result is very brittle and difficult to work with and therefore has limited use in manufacturing. Steel is an alloy, or mixture, of iron and a small but crucial amount of carbon that (depending on the quality of the iron used) produces a highly workable metal that was more suitable for shaping into rails for the expanding railroad industry. Birmingham’s local iron ore was high in phosphorus, which produced inferior steel. Sloss hoped to employ a new steelmaking process capable of eliminating phosphorus, but its patents were owned by Pennsylvania industrialist Andrew Carnegie and his Carnegie Steel Company. Thus, Sloss could not use them to manufacture the coveted alloy.

TCI’s Steelworks in Ensley

Birmingham industrialists continued to search for ways to produce quality steel, believing that the region’s low production costs, cheap labor, and close access to raw materials would make Birmingham the world’s greatest industrial city. TCI, by far Birmingham’s largest corporation, was run by businessmen who were more interested in stock speculation than in efficient operations. In 1892, TCI officials tried to lure the Sloss and DeBardeleben companies into a merger. DeBardeleben, unaware that TCI was close to bankruptcy, agreed to the deal and lost most of his fortune. Sloss officials, who were committed to a patient, conservative growth strategy, wisely backed out, and the company stayed independent.

TCI’s Steelworks in Ensley

Birmingham industrialists continued to search for ways to produce quality steel, believing that the region’s low production costs, cheap labor, and close access to raw materials would make Birmingham the world’s greatest industrial city. TCI, by far Birmingham’s largest corporation, was run by businessmen who were more interested in stock speculation than in efficient operations. In 1892, TCI officials tried to lure the Sloss and DeBardeleben companies into a merger. DeBardeleben, unaware that TCI was close to bankruptcy, agreed to the deal and lost most of his fortune. Sloss officials, who were committed to a patient, conservative growth strategy, wisely backed out, and the company stayed independent.

A nationwide depression in the 1890s caused mining and furnace companies in Alabama‘s northwest corner to fail. Sloss and TCI purchased some of these firms and greatly expanded their operations. Sloss reorganized as the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company in 1899 and became the second-largest iron manufacturer in the state. Later, outside investors from New York gained control of Sloss and TCI, and Pioneer was absorbed by Ohio-based Republic Iron and Steel Company, leaving Woodward as the only locally owned ironmaking firm.

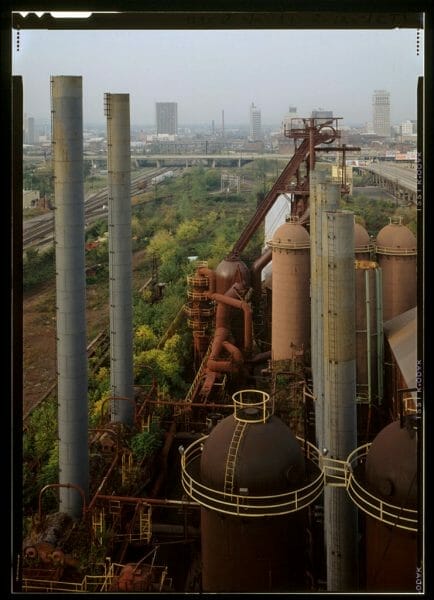

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

In 1895, TCI instituted a new process that reduced phosphorus and other impurities in the raw materials and began producing steel, but its quality still did not match that of the steel produced in northern factories. Four years later, the company was forced to adopt a much more complex and costly method of eliminating the phosphorus. Sloss-Sheffield, which had retained the word steel in its name when it officially incorporated, worked toward improving steel quality as well, but the company largely concentrated on making high-quality pig iron for the foundries that had begun moving to Alabama. Although phosphorus was a problem in steel-making, it enhanced iron’s liquidity and made it more suitable for molding, or casting, into waste and pressure pipes, stove plates, and a variety of intricate shapes. Woodward pursued the same strategy, and Alabama soon dominated the domestic foundry trade. Many local business leaders resented the deviation from the goal of steelmaking, however.

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

In 1895, TCI instituted a new process that reduced phosphorus and other impurities in the raw materials and began producing steel, but its quality still did not match that of the steel produced in northern factories. Four years later, the company was forced to adopt a much more complex and costly method of eliminating the phosphorus. Sloss-Sheffield, which had retained the word steel in its name when it officially incorporated, worked toward improving steel quality as well, but the company largely concentrated on making high-quality pig iron for the foundries that had begun moving to Alabama. Although phosphorus was a problem in steel-making, it enhanced iron’s liquidity and made it more suitable for molding, or casting, into waste and pressure pipes, stove plates, and a variety of intricate shapes. Woodward pursued the same strategy, and Alabama soon dominated the domestic foundry trade. Many local business leaders resented the deviation from the goal of steelmaking, however.

Republic Steel in Gadsden

In 1907, New York investment banker J. P. Morgan, who had recently created the world’s largest company, United States Steel Corporation, acquired control of TCI. Local supporters of the purchase initially believed that this development would guarantee Birmingham’s future greatness, but their expectations were wrong. U.S. Steel officials did not want TCI to compete with Pittsburgh and other steelmaking centers and imposed a discriminatory pricing formula, known as “Pittsburgh Plus,” that was essentially a fee placed on rail shipments from Alabama. This fee eliminated any price advantage that TCI might have had outside its immediate region. New management, including CEO George Gordon Crawford, also defied southern views of labor and social welfare by dramatically improving housing, education, and medical care for TCI’s largely black work force.

Republic Steel in Gadsden

In 1907, New York investment banker J. P. Morgan, who had recently created the world’s largest company, United States Steel Corporation, acquired control of TCI. Local supporters of the purchase initially believed that this development would guarantee Birmingham’s future greatness, but their expectations were wrong. U.S. Steel officials did not want TCI to compete with Pittsburgh and other steelmaking centers and imposed a discriminatory pricing formula, known as “Pittsburgh Plus,” that was essentially a fee placed on rail shipments from Alabama. This fee eliminated any price advantage that TCI might have had outside its immediate region. New management, including CEO George Gordon Crawford, also defied southern views of labor and social welfare by dramatically improving housing, education, and medical care for TCI’s largely black work force.

Birmingham Steel Worker Housing

Sloss-Sheffield modernized somewhat and profited from the foundry trade in the years preceding World War I. During the conflict, however, the company responded too slowly to the federal government’s demand that it support the war effort by building up-to-date coke ovens to capture previously wasted though valuable chemical by-products. TCI and Woodward had already installed such ovens, and government impatience led to a change in leadership. New coke ovens in North Birmingham were completed after the war. Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation, which helped design the ovens, took financial control of the firm and continued to modernize the blast furnaces. By the end of the 1920s, Sloss-Sheffield and Woodward were the largest producers of foundry pig iron in America, and Alabama had more foundries than any other state. Meanwhile, TCI continued to be Birmingham’s largest enterprise, but the constraints placed on it by parent company U.S. Steel kept output down. By the end of the decade, TCI had produced less than 3 percent of the steel made in the United States.

Birmingham Steel Worker Housing

Sloss-Sheffield modernized somewhat and profited from the foundry trade in the years preceding World War I. During the conflict, however, the company responded too slowly to the federal government’s demand that it support the war effort by building up-to-date coke ovens to capture previously wasted though valuable chemical by-products. TCI and Woodward had already installed such ovens, and government impatience led to a change in leadership. New coke ovens in North Birmingham were completed after the war. Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation, which helped design the ovens, took financial control of the firm and continued to modernize the blast furnaces. By the end of the 1920s, Sloss-Sheffield and Woodward were the largest producers of foundry pig iron in America, and Alabama had more foundries than any other state. Meanwhile, TCI continued to be Birmingham’s largest enterprise, but the constraints placed on it by parent company U.S. Steel kept output down. By the end of the decade, TCI had produced less than 3 percent of the steel made in the United States.

Miners in Birmingham, 1937

The Great Depression that began in 1929 devastated Birmingham’s economy. Production of steel and pig iron shrank to the lowest levels since 1896, and operations at TCI, Republic, Sloss-Sheffield, and Woodward were drastically curtailed. Business leaders fought bitterly against labor reforms enacted under the New Deal, particularly the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which aimed to raise the wages of southern laborers to the level of their northern counterparts. Labor unions won recognition against strong resistance, but unemployment reached unprecedented levels.

Miners in Birmingham, 1937

The Great Depression that began in 1929 devastated Birmingham’s economy. Production of steel and pig iron shrank to the lowest levels since 1896, and operations at TCI, Republic, Sloss-Sheffield, and Woodward were drastically curtailed. Business leaders fought bitterly against labor reforms enacted under the New Deal, particularly the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which aimed to raise the wages of southern laborers to the level of their northern counterparts. Labor unions won recognition against strong resistance, but unemployment reached unprecedented levels.

Economic conditions improved as the nation and industries geared up for World War II. U.S. Steel built a large new blast furnace at its Fairfield plant, and the TCI plant was running at full capacity by 1939. Sloss-Sheffield made valuable contributions to the ensuing war effort but was beset by strikes, and its earnings were restrained by federal taxes on excess profit aimed at discouraging war profiteering. A far-reaching change took place in 1942, when the United States Pipe and Foundry Company (USP&F) bought Sloss-Sheffield from Allied Chemical and Dye. USP&F ownership ensured Sloss-Sheffield a steady market for pig iron within the parent firm’s network of pipe foundries and other installations. The move paid off after the war, when profit taxes were lifted and earnings soared. Woodward, as always, continued to prosper. Meanwhile, federal courts found U.S. Steel’s “Pittsburgh Plus” pricing practice illegal, but the giant corporation imposed a new constraining freight-pricing structure that remained in effect until 1947, when TCI products were essentially limited to a 300-mile radius from Birmingham.

U.S. Pipe and Foundry Company

Demand for foundry pig iron remained high into the 1950s. Because Sloss-Sheffield’s earnings exceeded those of USP&F, the parent company absorbed its subsidiary in a 1952 merger to take advantage of its superior profitability. Soon after the merger, USP&F moved its headquarters to Birmingham. In 1956, it began building a massive, ultra-modern blast furnace in North Birmingham in response to increasing competition from overseas firms, but the move came too late. By the time the facility was ready for production in 1958, German and Japanese blast furnaces, ironically built with U.S. foreign aid, were exporting iron to the United States at prices lower than those of domestic producers. Sloss-Sheffield and Woodward lost markets to these competitors that they had previously dominated. Demand for TCI products also began to shrink because of foreign competition. In addition, the appearance of superior ductile iron further reduced the demand for USP&F foundry pig iron by the end of the decade.

U.S. Pipe and Foundry Company

Demand for foundry pig iron remained high into the 1950s. Because Sloss-Sheffield’s earnings exceeded those of USP&F, the parent company absorbed its subsidiary in a 1952 merger to take advantage of its superior profitability. Soon after the merger, USP&F moved its headquarters to Birmingham. In 1956, it began building a massive, ultra-modern blast furnace in North Birmingham in response to increasing competition from overseas firms, but the move came too late. By the time the facility was ready for production in 1958, German and Japanese blast furnaces, ironically built with U.S. foreign aid, were exporting iron to the United States at prices lower than those of domestic producers. Sloss-Sheffield and Woodward lost markets to these competitors that they had previously dominated. Demand for TCI products also began to shrink because of foreign competition. In addition, the appearance of superior ductile iron further reduced the demand for USP&F foundry pig iron by the end of the decade.

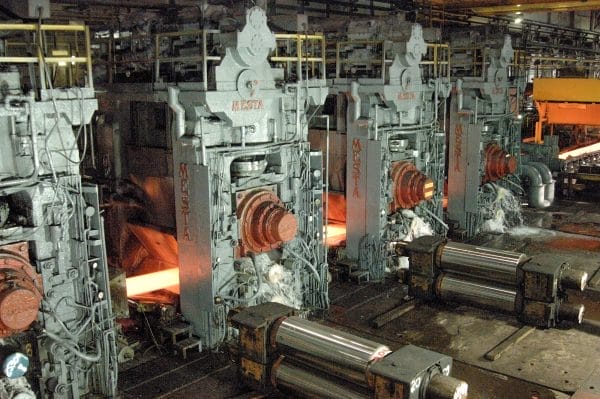

U.S. Steel Fairfield Works

Problems for Alabama’s iron and steel industry continued to mount. USP&F narrowly avoided a hostile takeover and was absorbed by the Jim Walter Corporation, a maker of prefabricated homes. The new owners soon realized that Alabama’s coal reserves, which remained plentiful, commanded higher prices in foreign markets than coke-fired pig iron, which was becoming uneconomical to produce. In 1970, USP&F’s last active furnace in Birmingham, one of the two that had been remodeled on the site of the original Sloss Furnace Company, shut down for good. In 1980, Jim Walter Corporation closed the huge new furnace that USP&F had erected in North Birmingham in 1956, then dismantled and sold it for scrap. Even Woodward, long the most profitable company in the Birmingham District, was forced out of business in the early 1970s, and only U.S. Steel’s Fairfield plant remained in production. The Fairfield facility is capable of producing up to 2.4 million tons of raw steel each year, with which it manufactures sheet metal and seamless tubular products.

U.S. Steel Fairfield Works

Problems for Alabama’s iron and steel industry continued to mount. USP&F narrowly avoided a hostile takeover and was absorbed by the Jim Walter Corporation, a maker of prefabricated homes. The new owners soon realized that Alabama’s coal reserves, which remained plentiful, commanded higher prices in foreign markets than coke-fired pig iron, which was becoming uneconomical to produce. In 1970, USP&F’s last active furnace in Birmingham, one of the two that had been remodeled on the site of the original Sloss Furnace Company, shut down for good. In 1980, Jim Walter Corporation closed the huge new furnace that USP&F had erected in North Birmingham in 1956, then dismantled and sold it for scrap. Even Woodward, long the most profitable company in the Birmingham District, was forced out of business in the early 1970s, and only U.S. Steel’s Fairfield plant remained in production. The Fairfield facility is capable of producing up to 2.4 million tons of raw steel each year, with which it manufactures sheet metal and seamless tubular products.

As Birmingham business leaders focused on new industries, such as professional services and a major medical school, small mills still made limited amounts of steel, but an era that had begun at Oxmoor Furnace in the 1870s had receded into the past. Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark, opened to the public in 1982, provides visitors with a glimpse of Birmingham’s industrial past and interprets its history in a museum that preserves the artifacts of the city’s once-great iron and steel industry.

Further Reading

- Armes, Ethel. The Story of Iron and Coal in Alabama. Leeds, Ala.: Beechwood Books, 1987.

- Flynt, Wayne, and Michael Thomason. Mine, Mill, and Microchip: A Chronicle of Alabama Enterprise. Northridge, Calif.: Windsor Publications, 1987.

- Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham Industrial District. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

- White, Marjorie Longenecker. The Birmingham District, An Industrial History and Guide. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Historical Society, 1981.