Samford University

Samford University Library

Samford University was founded by Baptists as Howard College in Marion, Perry County, in 1841. Located in Birmingham since 1887, the Christian school is Alabama’s largest private university and the state’s only private doctoral and research university, as classified by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Samford consists of Howard College of Arts and Sciences, Brock School of Business, Orlean Bullard Beeson School of Education and Professional Studies, School of the Arts, Ida V. Moffett School of Nursing, McWhorter School of Pharmacy, Beeson School of Divinity, and the Cumberland School of Law. In 2008, Samford was ranked 27th in the nation among all national universities by the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.

Samford University Library

Samford University was founded by Baptists as Howard College in Marion, Perry County, in 1841. Located in Birmingham since 1887, the Christian school is Alabama’s largest private university and the state’s only private doctoral and research university, as classified by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Samford consists of Howard College of Arts and Sciences, Brock School of Business, Orlean Bullard Beeson School of Education and Professional Studies, School of the Arts, Ida V. Moffett School of Nursing, McWhorter School of Pharmacy, Beeson School of Divinity, and the Cumberland School of Law. In 2008, Samford was ranked 27th in the nation among all national universities by the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.

Origins

Baptists began to shape education in Alabama soon after the state was established. In the 1820s, Baptist missionaries Lee and Susannah Compere travelled from the United Kingdom to Alabama and founded a school for Creek Indian children near present-day Tallassee. In the early 1830s, Lee Compere served on a committee that urged the Alabama Baptist State Convention to create a similar school to train Baptist ministers. The resulting school—called the Green County Institute of Literature and Industry—opened in Greensboro in 1836 and closed the next year, having failed to meet either its financial obligations or its original educational purpose. The labor required of students—farming and other chores—was not enough to help the school survive the national economic crisis of 1837, and the school did not exist long enough to establish the theological department required for the training of Baptist ministers.

Judson College

In 1841, a group of Baptists in the wealthy planter city of Marion invited the Alabama Baptist State Convention to establish a new school for men in the thriving town. Among the foremost advocates were Edwin D. King, an early settler of the town; northern-born Milo P. Jewett, president of Judson Female Institute in Marion; and native New Yorker James H. DeVotie, pastor of Marion’s Siloam Baptist Church. The men acquired land and funds for the new college from Julia Tarrant Barron, co-founder of the Baptist Judson Female Institute (now Judson College) and the Alabama Baptist newspaper. The convention agreed to the idea and the new school, located near Judson Female Institute, was named Howard College in honor of English prison reformer John Howard.

Judson College

In 1841, a group of Baptists in the wealthy planter city of Marion invited the Alabama Baptist State Convention to establish a new school for men in the thriving town. Among the foremost advocates were Edwin D. King, an early settler of the town; northern-born Milo P. Jewett, president of Judson Female Institute in Marion; and native New Yorker James H. DeVotie, pastor of Marion’s Siloam Baptist Church. The men acquired land and funds for the new college from Julia Tarrant Barron, co-founder of the Baptist Judson Female Institute (now Judson College) and the Alabama Baptist newspaper. The convention agreed to the idea and the new school, located near Judson Female Institute, was named Howard College in honor of English prison reformer John Howard.

Howard College welcomed its first nine students in January 1842 with a traditional curriculum of language, literature, and sciences. Attendance increased dramatically in the first years of operation—to 77 students by June 1843. Donations from Baptists throughout the state supplemented Howard’s meager tuition income, which in the college’s first term did not even pay for the living expenses of president and sole teacher Samuel Sterling Sherman.

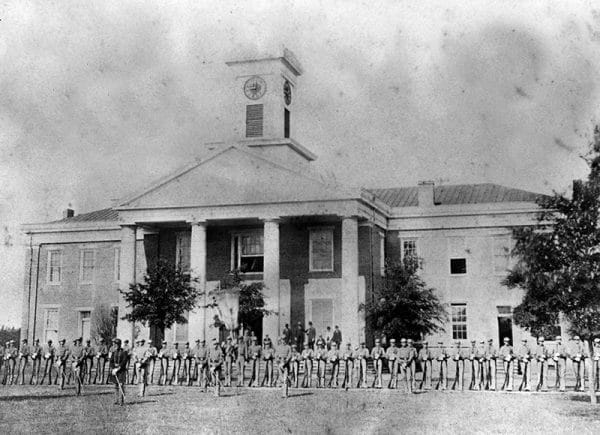

Howard College, 1858

Guided by trustees appointed by the Alabama Baptist State Convention, Howard College continued to grow, enrolling 152 students in the 1853-54 school year. Then, on October 15, 1854, fire destroyed all of Howard’s property—including its only building—and killed a student, a tutor, and a slave known only as Harry, who died while saving others. The college relocated away from the center of Marion to land donated by John T. Barron, son of Julia Barron and a member of the college’s first graduating class.

Howard College, 1858

Guided by trustees appointed by the Alabama Baptist State Convention, Howard College continued to grow, enrolling 152 students in the 1853-54 school year. Then, on October 15, 1854, fire destroyed all of Howard’s property—including its only building—and killed a student, a tutor, and a slave known only as Harry, who died while saving others. The college relocated away from the center of Marion to land donated by John T. Barron, son of Julia Barron and a member of the college’s first graduating class.

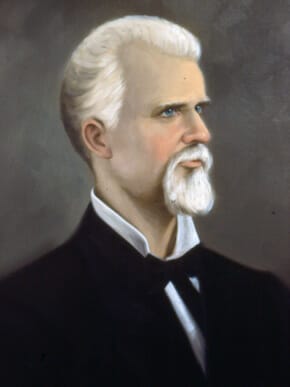

Murfee, James T.

Howard was still recovering from the fire of 1854 when the Civil War began. Students, faculty, and even the president volunteered for military service in 1861; thus Howard was barely functioning when the Confederate government asked to convert its campus into a military hospital in 1863. Howard’s trustees agreed to the arrangement, and although Howard ceased to function as a college for the rest of the war, remaining faculty did offer basic instruction to soldiers recovering at the hospital. Federal troops occupied Howard College for a short time after the war and sheltered freed slaves on its campus.

Murfee, James T.

Howard was still recovering from the fire of 1854 when the Civil War began. Students, faculty, and even the president volunteered for military service in 1861; thus Howard was barely functioning when the Confederate government asked to convert its campus into a military hospital in 1863. Howard’s trustees agreed to the arrangement, and although Howard ceased to function as a college for the rest of the war, remaining faculty did offer basic instruction to soldiers recovering at the hospital. Federal troops occupied Howard College for a short time after the war and sheltered freed slaves on its campus.

The college reopened in 1865 and was led by several short-term presidents—most notably J. L. M. Curry—before finding stable leadership in James T. Murfee in 1871. Murfee, a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute, commandant of cadets at the University of Alabama, and Confederate Army officer, brought to Howard a rigid military atmosphere that pleased many Howard supporters but frustrated others.

The East Lake Years

After the war, declining enrollments, local interracial strife, bankruptcy, and disagreements between Murfee and the Alabama Baptist State Convention led the organization to a difficult decision. In the 1880s, boosters from Birmingham promised to help the college grow if it would relocate to the East Lake community near the booming city. In return, they hoped, the college would bring prestige to the young city. The college accepted the East Lake Land Company’s offer of real estate and cash worth $170,075 and moved to East Lake in 1887, dividing Alabama Baptists and disappointing many residents of Marion. President Murfee opposed the move and remained on Howard’s Marion campus to form Marion Military Institute.

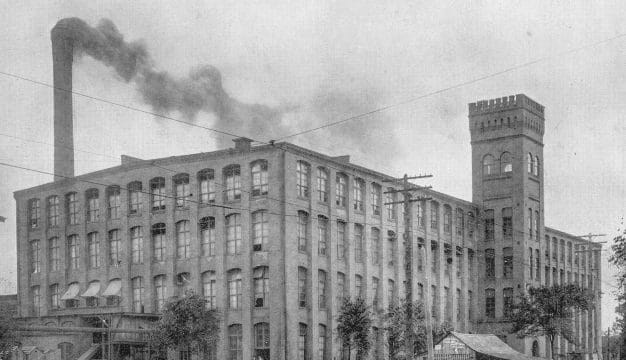

Howard Collage, East Lake, Old Main

Unfortunately, Birmingham’s economy fell on hard times just as Howard College settled into its new home. The college had to use its own meager funds to buy an important piece of land not included in the donations and was disappointed by the low level of financial support it found in Birmingham. Visions of a rich endowment and grand new college buildings were soon put aside. Optimism and local support returned by 1897, in large part as a result of the efforts of Howard president Albert D. Smith, who persuaded the East Lake Land Company to donate more land to the college and convinced Birmingham banker Burghard Steiner to personally guarantee payment of much of Howard’s debt, saving it from foreclosure. Although the college continued to grow in East Lake, hopes for a “greater Howard” were not realized for more than half a century.

Howard Collage, East Lake, Old Main

Unfortunately, Birmingham’s economy fell on hard times just as Howard College settled into its new home. The college had to use its own meager funds to buy an important piece of land not included in the donations and was disappointed by the low level of financial support it found in Birmingham. Visions of a rich endowment and grand new college buildings were soon put aside. Optimism and local support returned by 1897, in large part as a result of the efforts of Howard president Albert D. Smith, who persuaded the East Lake Land Company to donate more land to the college and convinced Birmingham banker Burghard Steiner to personally guarantee payment of much of Howard’s debt, saving it from foreclosure. Although the college continued to grow in East Lake, hopes for a “greater Howard” were not realized for more than half a century.

Howard College first admitted women students in 1894 but ended the practice because of a lack of facilities for women. Howard became fully and permanently coeducational in 1913, which helped the college survive declining enrollments during World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. Enrollment dropped 20 percent after the U.S. entered World War I, and the college began raising vegetables and livestock to feed the students. Women students made clothing for soldiers and many of the remaining men participated in the Student Army Training Corps. Howard President James M. Shelburn left the college for military service in 1917 and chose not to return at the end of his service.

Howard coped with the Great Depression by postponing new construction projects and otherwise reducing expenses. Faculty worked without pay during the worst of the crisis in the early 1930s. The college began to emerge from its economic troubles by the mid-1930s as federal aid increased enrollment.

Howard president Harwell Goodwin Davis, who served from 1939 to 1958, protected the school from more hard times during World War II by winning a contract with the federal government to host a branch of the U.S. Navy’s V-12 training program, which was designed to produce commissioned officers with college-level education. The program brought in more than 500 students to Howard, adding money and students at a time when both were in short supply.

Relocation and Prosperity

Samford University A. Hamilton Reid Chapel

Increased post-war enrollment raised the appeal of relocating Howard College, and president Davis had saved enough of the V-12 funds to allow Howard to leave behind the campus it was quickly outgrowing. By the late 1940s, Howard’s leaders had selected a site for a spacious new campus in Shades Valley, just south of Birmingham. The college moved to its present location in 1957, as Davis’s ambitious architectural vision for the new campus slowly took shape. Against the advice of some who wanted Howard to adopt modern architecture, Davis insisted that the college buildings be constructed in the red brick Georgian-Colonial style. The Quad—a large and carefully landscaped central green surrounded by Georgian-Colonial buildings—remains one of the university’s most popular places for study and relaxation for students.

Samford University A. Hamilton Reid Chapel

Increased post-war enrollment raised the appeal of relocating Howard College, and president Davis had saved enough of the V-12 funds to allow Howard to leave behind the campus it was quickly outgrowing. By the late 1940s, Howard’s leaders had selected a site for a spacious new campus in Shades Valley, just south of Birmingham. The college moved to its present location in 1957, as Davis’s ambitious architectural vision for the new campus slowly took shape. Against the advice of some who wanted Howard to adopt modern architecture, Davis insisted that the college buildings be constructed in the red brick Georgian-Colonial style. The Quad—a large and carefully landscaped central green surrounded by Georgian-Colonial buildings—remains one of the university’s most popular places for study and relaxation for students.

Completion of Davis’s vision of the physical campus fell to the next president, Leslie S. Wright, who served from 1958 to 1983. In 1961, the college acquired Cumberland School of Law, established in Lebanon, Tennessee, in 1847. In addition to the law school, Howard added new degree programs and reorganized to achieve university status in 1965. The name “Howard University” was already taken, so the trustees chose to name the new university in honor of the family of longtime trustee Frank Park Samford. Howard College of Arts and Sciences remained Samford’s academic core.

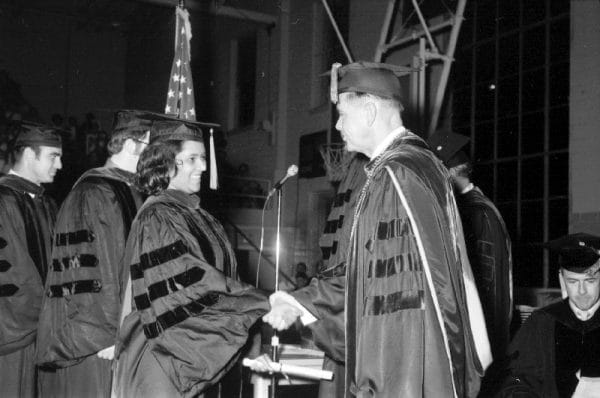

Audrey L. Gaston Graduation

Samford denied African Americans admittance until the late 1960s, although some faculty and students increasingly opposed that policy. The university’s whites-only admission policy threatened federal student aid and institutional accreditation. Cumberland School of Law faced the most immediate trouble because both the American Bar Association and Association of American Law Schools prohibited racial segregation at approved law schools. Cumberland admitted Samford’s first black student, Audrey Lattimore Gaston, in 1967. The entire university was integrated within a few years.

Audrey L. Gaston Graduation

Samford denied African Americans admittance until the late 1960s, although some faculty and students increasingly opposed that policy. The university’s whites-only admission policy threatened federal student aid and institutional accreditation. Cumberland School of Law faced the most immediate trouble because both the American Bar Association and Association of American Law Schools prohibited racial segregation at approved law schools. Cumberland admitted Samford’s first black student, Audrey Lattimore Gaston, in 1967. The entire university was integrated within a few years.

President Thomas E. Corts, who served from 1983 to 2006, led Samford during a period of increased recognition and respect as it began appearing in national college rankings and significantly expanded its international programs. Enrollment, facilities, endowment, and academic and athletic programs grew rapidly, in large part because of financial gifts totaling more than $100 million from benefactor Ralph W. Beeson and his extended family. By the end of the Corts administration, Samford had built an endowment of more than $250 million.

Samford, Frank P.

In 1994, Samford’s Board of Trustees voted to allow the board to elect its own members, giving the university independence from the Alabama Baptist Convention and shielding it from some of the political and theological disagreements that have characterized Southern Baptist culture since the 1970s. The Alabama Baptist Convention continues to make significant financial contributions to Samford and the university’s trustees and key administrators remain Baptist, but the university’s faculty, staff, and student populations increasingly exhibit greater theological and cultural diversity. Currently, Samford enrolls approximately 4,500 undergraduate and graduate students. Baptist undergraduates are outnumbered by undergraduates with other religious beliefs or no reported religious affiliation. Samford’s 17 men’s and women’s athletic teams, nicknamed the Bulldogs, compete in the Division I Southern Conference.

Samford, Frank P.

In 1994, Samford’s Board of Trustees voted to allow the board to elect its own members, giving the university independence from the Alabama Baptist Convention and shielding it from some of the political and theological disagreements that have characterized Southern Baptist culture since the 1970s. The Alabama Baptist Convention continues to make significant financial contributions to Samford and the university’s trustees and key administrators remain Baptist, but the university’s faculty, staff, and student populations increasingly exhibit greater theological and cultural diversity. Currently, Samford enrolls approximately 4,500 undergraduate and graduate students. Baptist undergraduates are outnumbered by undergraduates with other religious beliefs or no reported religious affiliation. Samford’s 17 men’s and women’s athletic teams, nicknamed the Bulldogs, compete in the Division I Southern Conference.

Additional Resources

Flynt, Sean. 160 Years of Samford University: For God, For Learning, Forever. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2001.

Garrett, Mitchell Bennett. Sixty Years of Howard College, 1842-1902. Birmingham, Ala.: Samford University, 1927.

Langum, David J., and Howard P. Walthall. From Maverick to Mainstream: Cumberland School of Law, 1847-1997. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

Sulzby, James F., Jr. Toward a History of Samford University. Birmingham, Ala.: Samford University Press, 1986.