Modern Civil Rights Movement in Alabama

Selma to Montgomery March End

The modern civil rights movement in Alabama burst into public consciousness with a single act of civil disobedience by Rosa Parks in Montgomery in 1955. It began to fade from the public eye a decade later, following the formation of the original Black Panther Party in Lowndes County. During the intervening years, Alabama was the site of some of the most defining events of the civil rights era. These events transformed the state and profoundly changed America.

Selma to Montgomery March End

The modern civil rights movement in Alabama burst into public consciousness with a single act of civil disobedience by Rosa Parks in Montgomery in 1955. It began to fade from the public eye a decade later, following the formation of the original Black Panther Party in Lowndes County. During the intervening years, Alabama was the site of some of the most defining events of the civil rights era. These events transformed the state and profoundly changed America.

Black protest started long before the civil rights movement emerged and continued long after it stopped receiving front-page headlines. African Americans in Alabama began fighting for basic civil and human rights as soon as slavery ended in 1865, and they continue to fight for these rights today. Although they have adjusted their tactics to fit the times, their goals have changed very little. They have fought consistently for social autonomy, quality education, political power, and an acceptable standard of living. They have also fought to end racial terrorism and to enjoy the fruits of their own labor. On the continuum of black protest, however, the 1950s and 1960s were unique. During these years, black protest involved more people, was more highly organized, and lasted longer than any other period of activism. It also featured the most direct challenges to segregation and produced the most dramatic gains.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

On Thursday, December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, an African American seamstress, boarded a city bus in downtown Montgomery and sat one row behind the whites-only section. As the bus filled with passengers, the white driver ordered Parks to surrender her seat to a white man. Parks refused. Her defiance prompted the driver to summon the police, who promptly arrested her for violating the city’s segregation ordinance.

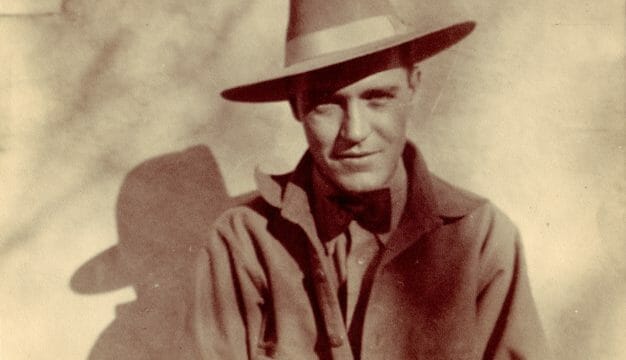

E. D. Nixon

Parks had been involved in the fight for civil rights for some time. She was an active member of the Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). That summer, she had also taken a trip to the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, to participate in civil rights workshops. Virginia Durr, a white southern reformer who had befriended Parks, arranged the trip. When Virginia’s husband, Clifford Durr, a prominent lawyer known for accepting civil liberties cases, and E. D. Nixon, the president of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, learned of Parks’s arrest, they bailed her out. They also contacted Jo Anne Robinson, the president of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), who immediately organized a one-day bus boycott. Montgomery’s black residents responded enthusiastically to the call to stay off the buses because so many had suffered similar indignities for so long.

E. D. Nixon

Parks had been involved in the fight for civil rights for some time. She was an active member of the Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). That summer, she had also taken a trip to the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, to participate in civil rights workshops. Virginia Durr, a white southern reformer who had befriended Parks, arranged the trip. When Virginia’s husband, Clifford Durr, a prominent lawyer known for accepting civil liberties cases, and E. D. Nixon, the president of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, learned of Parks’s arrest, they bailed her out. They also contacted Jo Anne Robinson, the president of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), who immediately organized a one-day bus boycott. Montgomery’s black residents responded enthusiastically to the call to stay off the buses because so many had suffered similar indignities for so long.

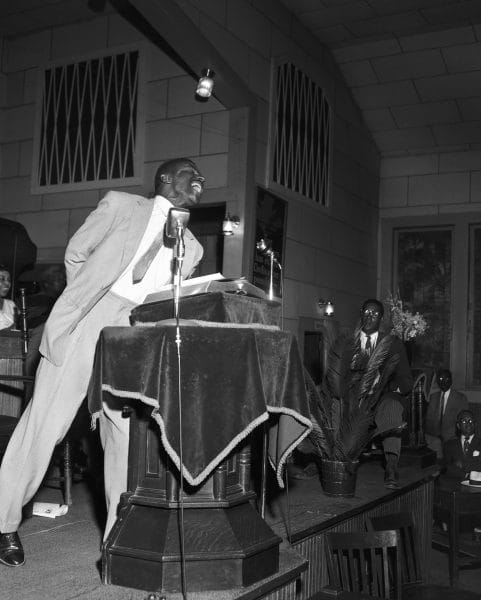

On Monday, December 5, 1955, some 30,000 African Americans participated in the bus boycott. That afternoon, the leaders of the African American community, including Ralph David Abernathy, the pastor of First Baptist Church, formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to coordinate future protests. They also appointed Abernathy’s close friend Martin Luther King Jr., the 26-year-old pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, president of the organization. This fateful decision thrust the young preacher to the forefront of the boycott and into the national spotlight. That same evening, King and the MIA held a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church. Ordinary black folk filled the pews and voted overwhelmingly to continue the boycott.

Martin Luther King and Bus Boycott Organizers

Soon after the boycott began, MIA representatives met with Montgomery mayor William A. Gayle and other city leaders and explained that African Americans would not resume riding the buses until the bus company hired black drivers for routes through black neighborhoods and instructed white drivers to treat black passengers with courtesy and professionalism. They also informed Gayle that they wanted a seating arrangement similar to the one instituted in Mobile, which permitted African Americans to begin filling buses from the back to the front, and whites from the front to the back. Although their demands were well within the bounds of Jim Crow traditions, the city leaders rejected them outright. Their stubbornness prompted Fred Gray, a local black attorney, to file a lawsuit in federal court. The lawsuit, known as Browder v. Gayle, sought a complete end to segregation on the city’s buses. As Browder v. Gayle wound its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, the MIA sustained the bus boycott by developing an intricate carpool system that involved several hundred drivers. City police harassed the boycott’s supporters, and white terrorists targeted the boycott’s leaders. On January 30, 1956, they bombed King’s home, and two days later, they bombed E. D. Nixon’s home.

Martin Luther King and Bus Boycott Organizers

Soon after the boycott began, MIA representatives met with Montgomery mayor William A. Gayle and other city leaders and explained that African Americans would not resume riding the buses until the bus company hired black drivers for routes through black neighborhoods and instructed white drivers to treat black passengers with courtesy and professionalism. They also informed Gayle that they wanted a seating arrangement similar to the one instituted in Mobile, which permitted African Americans to begin filling buses from the back to the front, and whites from the front to the back. Although their demands were well within the bounds of Jim Crow traditions, the city leaders rejected them outright. Their stubbornness prompted Fred Gray, a local black attorney, to file a lawsuit in federal court. The lawsuit, known as Browder v. Gayle, sought a complete end to segregation on the city’s buses. As Browder v. Gayle wound its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, the MIA sustained the bus boycott by developing an intricate carpool system that involved several hundred drivers. City police harassed the boycott’s supporters, and white terrorists targeted the boycott’s leaders. On January 30, 1956, they bombed King’s home, and two days later, they bombed E. D. Nixon’s home.

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

On November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower-court ruling declaring that segregation on Montgomery buses was unconstitutional. One month later, African Americans integrated the city’s bus system, ending the 381-day boycott. The successful protest was a source of inspiration for African Americans nationwide. The high rate of black participation and the sophisticated nature of the mobilization effort demonstrated what African Americans were capable of achieving. The boycott also breathed new life into black protest by introducing King to the nation. The victory, however, did not end segregation beyond the city buses. Nor did it end racial violence. On January 10, 1957, white terrorists bombed Abernathy’s home.

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

On November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower-court ruling declaring that segregation on Montgomery buses was unconstitutional. One month later, African Americans integrated the city’s bus system, ending the 381-day boycott. The successful protest was a source of inspiration for African Americans nationwide. The high rate of black participation and the sophisticated nature of the mobilization effort demonstrated what African Americans were capable of achieving. The boycott also breathed new life into black protest by introducing King to the nation. The victory, however, did not end segregation beyond the city buses. Nor did it end racial violence. On January 10, 1957, white terrorists bombed Abernathy’s home.

The Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights

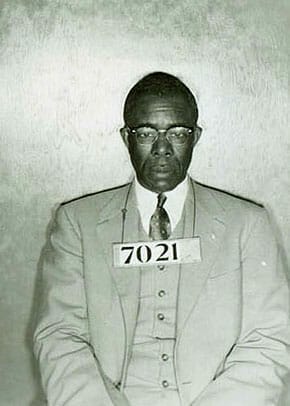

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

In response to the boycott’s success, state officials conspired to prevent future outbreaks of black protest by trying to silence the NAACP. John Patterson, the Alabama attorney general and soon-to-be governor of the state, led the effort. Using a loophole in state law, he managed to shut down local NAACP branches. As the nation’s leading civil rights organization, the absence of the NAACP created a noticeable void in the black community. In Birmingham, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), founded on June 5, 1956, filled this empty space. Fred Shuttlesworth, a fiery orator and the pastor of Bethel Baptist Church, headed the organization. Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR fought admirably to end segregation in the “Magic City” but made very little headway on their own. The slow pace of progress over the next several years eventually led them to invite outside organizers to help them with the struggle. King was among those who would answer the call.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

In response to the boycott’s success, state officials conspired to prevent future outbreaks of black protest by trying to silence the NAACP. John Patterson, the Alabama attorney general and soon-to-be governor of the state, led the effort. Using a loophole in state law, he managed to shut down local NAACP branches. As the nation’s leading civil rights organization, the absence of the NAACP created a noticeable void in the black community. In Birmingham, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), founded on June 5, 1956, filled this empty space. Fred Shuttlesworth, a fiery orator and the pastor of Bethel Baptist Church, headed the organization. Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR fought admirably to end segregation in the “Magic City” but made very little headway on their own. The slow pace of progress over the next several years eventually led them to invite outside organizers to help them with the struggle. King was among those who would answer the call.

Tuskegee’s Fight for Voting Rights

State officials did not limit their attempts to preserve segregation to neutralizing the NAACP. They also tried to make it even more difficult for African Americans to gain political power. In Tuskegee, where African Americans had been registering to vote in increasing numbers since the early 1950s, the state legislature redrew the city’s boundaries in 1957 in such a way as to exclude the vast majority of them. This blatant act of gerrymandering robbed African Americans of the right to participate in city elections. In response, the city’s black residents launched a boycott against local white businesses. In 1958, Charles Gomillion, a sociology professor at Tuskegee University and the president of the Tuskegee Civic Association (TCA), filed suit in federal court to return the city to its original boundaries. Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Gomillion v. Lightfoot that the city’s original boundaries had to be restored. This ruling established an important judicial precedent for court intervention in voting-rights cases. It also energized local African Americans. The continuation of social segregation, however, was tremendously disappointing. It was especially disheartening to students at Tuskegee University, who were a part of the emerging cadre of young activists who would redefine black protest in the 1960s.

Sit-Ins and Freedom Rides

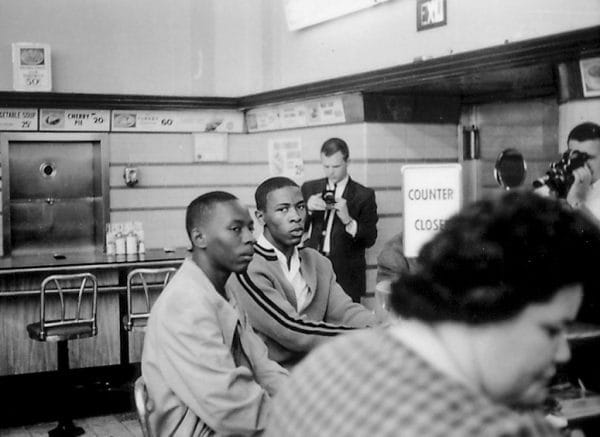

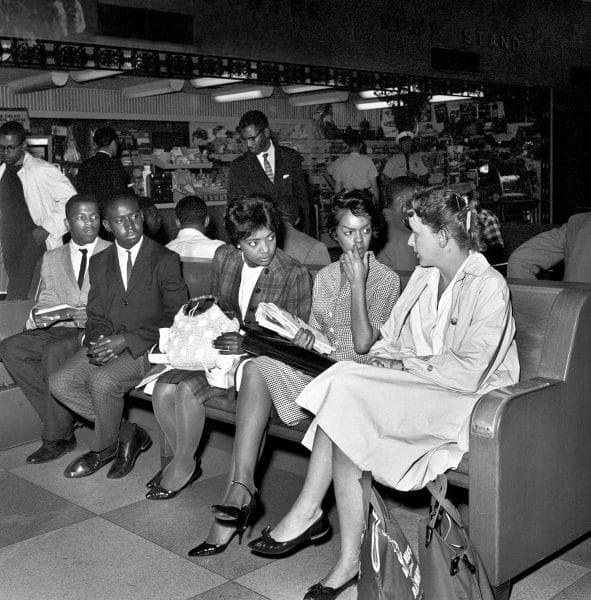

Lunch Counter Sit In

On February 1, 1960, several black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, conducted a sit-in at a lunch counter in a Woolworth’s department store. The protest encouraged black students across Alabama. In Montgomery, students at Alabama State University were among the first to organize. Soon after the Greensboro sit-in, three dozen Alabama State students attempted to eat at the segregated cafeteria in the state capitol. None of them was surprised when cafeteria workers refused to serve them, but they were all shocked when school president Councill Trenholm expelled them at the insistence of Governor Patterson. Several thousand students held a rally in support of their classmates at Hutchinson Street Baptist Church, and at least as many marched on the capitol the following day. The willingness of black students to challenge the authority of the state placed them on the frontline of the civil rights movement, where they remained for the rest of the decade.

Lunch Counter Sit In

On February 1, 1960, several black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, conducted a sit-in at a lunch counter in a Woolworth’s department store. The protest encouraged black students across Alabama. In Montgomery, students at Alabama State University were among the first to organize. Soon after the Greensboro sit-in, three dozen Alabama State students attempted to eat at the segregated cafeteria in the state capitol. None of them was surprised when cafeteria workers refused to serve them, but they were all shocked when school president Councill Trenholm expelled them at the insistence of Governor Patterson. Several thousand students held a rally in support of their classmates at Hutchinson Street Baptist Church, and at least as many marched on the capitol the following day. The willingness of black students to challenge the authority of the state placed them on the frontline of the civil rights movement, where they remained for the rest of the decade.

Freedom Riders in Birmingham

The civil rights movement in Alabama reached a new level of intensity when the Freedom Riders entered the state in May 1961. The racially integrated group of activists rode Greyhound and Trailways buses across the South to test compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which forbade racial discrimination in interstate travel. John Lewis, a native of Pike County and a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was one of the group’s leaders. On Sunday, May 14, 1961—Mother’s Day—some 200 white men attacked the first bus of Freedom Riders with bats and pipes when it reached Anniston; they later firebombed it. The Freedom Riders barely escaped the burning bus, and as they stumbled out of the flaming ruin, the white mob attacked again. Only the presence of an Alabama Public Safety officer prevented a death from occurring. In Birmingham, another mob beat a second group of Freedom Riders when their bus pulled into the city’s downtown bus station.

Freedom Riders in Birmingham

The civil rights movement in Alabama reached a new level of intensity when the Freedom Riders entered the state in May 1961. The racially integrated group of activists rode Greyhound and Trailways buses across the South to test compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which forbade racial discrimination in interstate travel. John Lewis, a native of Pike County and a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was one of the group’s leaders. On Sunday, May 14, 1961—Mother’s Day—some 200 white men attacked the first bus of Freedom Riders with bats and pipes when it reached Anniston; they later firebombed it. The Freedom Riders barely escaped the burning bus, and as they stumbled out of the flaming ruin, the white mob attacked again. Only the presence of an Alabama Public Safety officer prevented a death from occurring. In Birmingham, another mob beat a second group of Freedom Riders when their bus pulled into the city’s downtown bus station.

Freedom Rides

SNCC leaders in Nashville quickly sent reinforcements to Alabama. But when the second wave of Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery on May 20, 1961, the city police refused to protect them. Instead, they allowed a group of whites to attack them as they disembarked. The assault sent John Lewis and several others to the hospital. This round of violence embarrassed and infuriated U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy and caused him to pressure Governor Patterson to provide the Freedom Riders with safe passage into Mississippi. Once there, the Freedom Riders were arrested and jailed. Their demonstration was a turning point in the Alabama civil rights movement, however. The Freedom Rides refocused attention on segregation and racial violence in the state and forced Pres. John F. Kennedy to take decisive action to protect the civil rights activists. Unfortunately, the president did not make protecting civil rights workers a permanent priority, which left them exposed to white violence.

Freedom Rides

SNCC leaders in Nashville quickly sent reinforcements to Alabama. But when the second wave of Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery on May 20, 1961, the city police refused to protect them. Instead, they allowed a group of whites to attack them as they disembarked. The assault sent John Lewis and several others to the hospital. This round of violence embarrassed and infuriated U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy and caused him to pressure Governor Patterson to provide the Freedom Riders with safe passage into Mississippi. Once there, the Freedom Riders were arrested and jailed. Their demonstration was a turning point in the Alabama civil rights movement, however. The Freedom Rides refocused attention on segregation and racial violence in the state and forced Pres. John F. Kennedy to take decisive action to protect the civil rights activists. Unfortunately, the president did not make protecting civil rights workers a permanent priority, which left them exposed to white violence.

The Struggle in Birmingham

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

After the Freedom Riders left Alabama, the civil rights effort lost some of its energy, but their absence did not keep African Americans from continuing to fight for their rights. In Birmingham, Fred Shuttlesworth was among those who carried the struggle forward. As the president of ACMHR, he had been at the forefront of the movement in the city since 1956. In September 1962, the fearless preacher helped secure a promise from white civic leaders to desegregate downtown water fountains and restrooms, a major accomplishment given Birmingham’s reputation as the most segregated city in America. When the white leaders reneged on the agreement a few months later, Shuttlesworth appealed to King for help. By that time, King was the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a national civil rights group established in the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

After the Freedom Riders left Alabama, the civil rights effort lost some of its energy, but their absence did not keep African Americans from continuing to fight for their rights. In Birmingham, Fred Shuttlesworth was among those who carried the struggle forward. As the president of ACMHR, he had been at the forefront of the movement in the city since 1956. In September 1962, the fearless preacher helped secure a promise from white civic leaders to desegregate downtown water fountains and restrooms, a major accomplishment given Birmingham’s reputation as the most segregated city in America. When the white leaders reneged on the agreement a few months later, Shuttlesworth appealed to King for help. By that time, King was the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a national civil rights group established in the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott.

“Bull” Connor in 1963

SCLC organized an elaborate campaign to desegregate Birmingham. The operation involved sit-ins, marches, and a boycott of downtown stores. The initiative began on April 3, 1963, with a series of small demonstrations. As the protests intensified, so too did the reaction of Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, who deployed police with German shepherds to disrupt them. At the behest of Bull Conner, Judge William A. Jenkins Jr. issued a court injunction forbidding public protest, but King disobeyed the order as a matter of principle. His defiance resulted in his immediate arrest. While behind bars, he wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he chastised white clergy for not getting involved in the freedom struggle. After King’s arrest, SCLC brought in elementary and high school students for the Children’s Crusade to revitalize the campaign. In a remarkable display of collective courage, the children faced high-pressure water hoses as they marched through Kelly Ingram Park and the city’s streets.

“Bull” Connor in 1963

SCLC organized an elaborate campaign to desegregate Birmingham. The operation involved sit-ins, marches, and a boycott of downtown stores. The initiative began on April 3, 1963, with a series of small demonstrations. As the protests intensified, so too did the reaction of Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, who deployed police with German shepherds to disrupt them. At the behest of Bull Conner, Judge William A. Jenkins Jr. issued a court injunction forbidding public protest, but King disobeyed the order as a matter of principle. His defiance resulted in his immediate arrest. While behind bars, he wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he chastised white clergy for not getting involved in the freedom struggle. After King’s arrest, SCLC brought in elementary and high school students for the Children’s Crusade to revitalize the campaign. In a remarkable display of collective courage, the children faced high-pressure water hoses as they marched through Kelly Ingram Park and the city’s streets.

Good Friday March

Connor hoped that his harsh tactics would intimidate them, but each day more people joined the protests. In addition, news footage of children being thrown down by blasts of water from the hoses and bitten by police dogs damaged the city’s image. The negative publicity prompted white civic leaders to negotiate a settlement. On May 10, 1963, King announced a gradual desegregation agreement. It was less than what the people wanted, but more than what they had. The agreement brought the demonstrations to a halt, but it did not end white violence. On September 15, 1963, a bomb exploded at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church just before the start of Sunday school, killing Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Denise McNair, and Carole Robertson, who ranged in age from 11 to 14 years old.

Good Friday March

Connor hoped that his harsh tactics would intimidate them, but each day more people joined the protests. In addition, news footage of children being thrown down by blasts of water from the hoses and bitten by police dogs damaged the city’s image. The negative publicity prompted white civic leaders to negotiate a settlement. On May 10, 1963, King announced a gradual desegregation agreement. It was less than what the people wanted, but more than what they had. The agreement brought the demonstrations to a halt, but it did not end white violence. On September 15, 1963, a bomb exploded at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church just before the start of Sunday school, killing Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Denise McNair, and Carole Robertson, who ranged in age from 11 to 14 years old.

Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

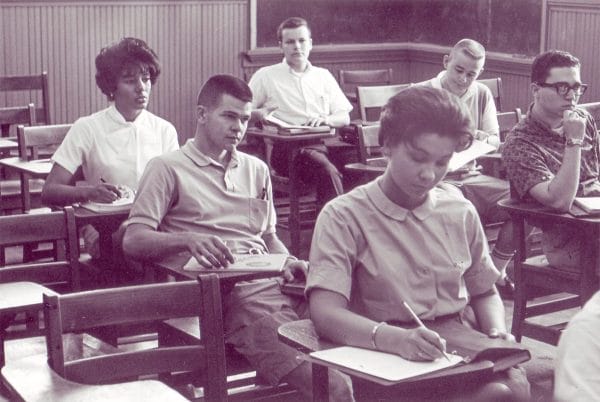

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

In June 1963, national attention shifted momentarily away from Birmingham to Tuscaloosa, where Vivian Malone and James Hood, black students from Mobile and Gadsden, attempted to enroll at the University of Alabama, the state’s flagship university. The university was still all white, despite countless attempts to desegregate it over the preceding decade, including a valiant attempt by Autherine Lucy, a native of Marengo County who attended classes briefly in 1956 before university trustees suspended her because of rioting by white students and others. U.S. district judge Seybourn Lynne forbade Gov. George Wallace from interfering with the registration of Malone and Hood, but on June 11, 1963, Wallace made a great show of public defiance in front of Foster Auditorium on campus. Later that same day, he yielded to federal pressure and allowed the two students to register. In 1965, Malone became the first African American to graduate from the university.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

In June 1963, national attention shifted momentarily away from Birmingham to Tuscaloosa, where Vivian Malone and James Hood, black students from Mobile and Gadsden, attempted to enroll at the University of Alabama, the state’s flagship university. The university was still all white, despite countless attempts to desegregate it over the preceding decade, including a valiant attempt by Autherine Lucy, a native of Marengo County who attended classes briefly in 1956 before university trustees suspended her because of rioting by white students and others. U.S. district judge Seybourn Lynne forbade Gov. George Wallace from interfering with the registration of Malone and Hood, but on June 11, 1963, Wallace made a great show of public defiance in front of Foster Auditorium on campus. Later that same day, he yielded to federal pressure and allowed the two students to register. In 1965, Malone became the first African American to graduate from the university.

Vivian Malone

President Kennedy followed the events that were taking place in Tuscaloosa closely. On the same evening as Wallace’s “stand in the schoolhouse door,” as it became known, Kennedy addressed the nation and announced his intention to send a new civil rights bill to Congress. In July 1964, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, signed the legislation into law, which now prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and hiring. One of the earliest tests of compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act occurred in Selma, where SNCC field secretaries Bernard and Colia Lafayette had been organizing African Americans since 1962.

Vivian Malone

President Kennedy followed the events that were taking place in Tuscaloosa closely. On the same evening as Wallace’s “stand in the schoolhouse door,” as it became known, Kennedy addressed the nation and announced his intention to send a new civil rights bill to Congress. In July 1964, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, signed the legislation into law, which now prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and hiring. One of the earliest tests of compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act occurred in Selma, where SNCC field secretaries Bernard and Colia Lafayette had been organizing African Americans since 1962.

Selma

In many parts of Alabama, slow progress was being made. In Anniston, an interracial group of clergy worked to end segregation incrementally. In Huntsville, local activists desegregated downtown businesses and were close to desegregating the public schools by 1962. And in Tuscaloosa, the Tuscaloosa Citizens for Action Committee (TCAC), aided by an armed African American self-defense group, desegregated downtown lunch counters and city buses. But in Selma, segregation and disenfranchisement endured.

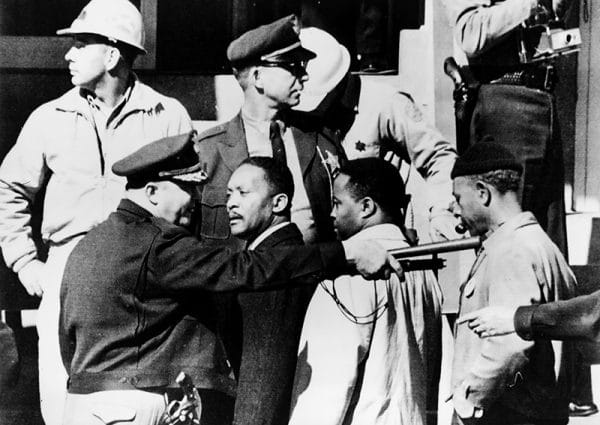

Sheriff Clark and Demonstrators

In July 1964, the Lafayettes organized a series of nonviolent, direct-action protests in downtown Selma, but Dallas County sheriff Jim Clark defeated the campaign with violence. Black protest subsided until January 1965, when SCLC and SNCC launched a joint effort to draw attention to the denial of black voting rights locally and throughout the South. Their goal was to secure the vote for African Americans in Dallas County and win support for federal voting-rights legislation. To dramatize black disenfranchisement, the two organizations, in collaboration with the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL), organized several marches on the county courthouse, beginning January 18, 1965. Not surprisingly, Sheriff Clark harassed and arrested the demonstrators, including King.

Sheriff Clark and Demonstrators

In July 1964, the Lafayettes organized a series of nonviolent, direct-action protests in downtown Selma, but Dallas County sheriff Jim Clark defeated the campaign with violence. Black protest subsided until January 1965, when SCLC and SNCC launched a joint effort to draw attention to the denial of black voting rights locally and throughout the South. Their goal was to secure the vote for African Americans in Dallas County and win support for federal voting-rights legislation. To dramatize black disenfranchisement, the two organizations, in collaboration with the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL), organized several marches on the county courthouse, beginning January 18, 1965. Not surprisingly, Sheriff Clark harassed and arrested the demonstrators, including King.

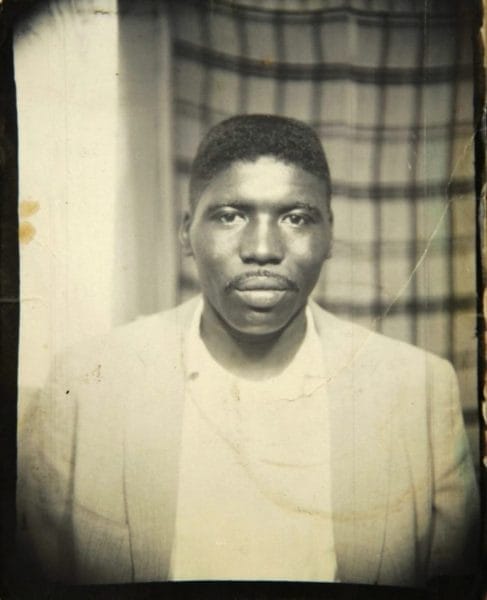

Jimmie Lee Jackson

The Selma campaign began to wane near the end of February 1965. At the same time, civil rights organizing increased in the rural Black Belt counties surrounding the city. In Perry and Wilcox Counties, voters’ leagues, loosely affiliated with SCLC, led the way. The cause gained renewed vigor when a state trooper fatally wounded 26-year-old local activist Jimmie Lee Jackson during a night march in Perry County. To honor Jackson’s memory and highlight his sacrifice, SCLC organized a march from Selma to the governor’s doorstep in Montgomery. On March 7, 1965, as several hundred marchers crossed Selma’s steeply arched Edmund Pettus Bridge, Clark’s posse and state troopers brutally beat them. That evening, the television networks broadcast footage of what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” bringing the violence of Jim Crow into the living rooms of millions of Americans.

Jimmie Lee Jackson

The Selma campaign began to wane near the end of February 1965. At the same time, civil rights organizing increased in the rural Black Belt counties surrounding the city. In Perry and Wilcox Counties, voters’ leagues, loosely affiliated with SCLC, led the way. The cause gained renewed vigor when a state trooper fatally wounded 26-year-old local activist Jimmie Lee Jackson during a night march in Perry County. To honor Jackson’s memory and highlight his sacrifice, SCLC organized a march from Selma to the governor’s doorstep in Montgomery. On March 7, 1965, as several hundred marchers crossed Selma’s steeply arched Edmund Pettus Bridge, Clark’s posse and state troopers brutally beat them. That evening, the television networks broadcast footage of what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” bringing the violence of Jim Crow into the living rooms of millions of Americans.

Bloody Sunday

In the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday,” King issued a call for civil and human rights supporters to come to Selma to join another march on March 9. James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Boston, was among the many thousands who answered the call. Soon after arriving in Selma, however, he was beaten by a group of young white men and died two days later.

Bloody Sunday

In the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday,” King issued a call for civil and human rights supporters to come to Selma to join another march on March 9. James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Boston, was among the many thousands who answered the call. Soon after arriving in Selma, however, he was beaten by a group of young white men and died two days later.

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, after three weeks of legal battles, the Selma-to-Montgomery March finally resumed. U.S. district judge Frank M. Johnson ordered Alabama officials not to interfere with the demonstration. He also limited the number of people who could walk the entire 50 miles along U.S. Highway 80 to a few hundred, but more than 20,000 people joined the marchers five days later on the stark white steps of the state capitol. There they listened to King deliver a stirring speech on freedom, justice, and equality. That same evening, Viola Liuzzo, a white activist who had travelled to Alabama from Michigan to participate in the march, was murdered as she and black activist Leroy Moton shuttled marchers between Montgomery and Selma.

Events in Selma cleared the way for President Johnson to sponsor legislation to protect black voting rights. In August 1965, the U.S. Congress passed the landmark Voting Rights Act, which banned literacy tests and permitted federal registrars to add eligible African Americans to the voting rolls. Attorneys from the U.S. Justice Department who had litigated voting rights cases in the Alabama Black Belt for several years played a prominent role in drafting the key provisions of the new law. The city is now a center of the National Civil Rights Trail, with the Selma Interpretive Center, as well as the nearby Lowndes Interpretive Center, both operated by the National Park Service, serving as visitor’s centers.

The Rise of the Black Power Movement

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act ushered in the era of black re-enfranchisement. But after African Americans gained access to the ballot box, they had to decide whether or not to support the Alabama Democratic Party, which publicly embraced white supremacy. In Lowndes County, the leaders of the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights (LCCMHR) decided to organize an all-black, countywide, third party—the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The group chose as the party’s ballot symbol a snarling black panther, which earned the LCFO the nickname the Black Panther Party. The symbol inspired African Americans across the country, including the founders of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, who named their organization after the LCFO symbol. A team of SNCC field secretaries, led by Stokely Carmichael, helped Lowndes County activists build the LCFO. The SNCC workers also drew upon this experience to develop the theories and programs behind Black Power, which Carmichael introduced to the nation during the summer of 1966.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act ushered in the era of black re-enfranchisement. But after African Americans gained access to the ballot box, they had to decide whether or not to support the Alabama Democratic Party, which publicly embraced white supremacy. In Lowndes County, the leaders of the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights (LCCMHR) decided to organize an all-black, countywide, third party—the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The group chose as the party’s ballot symbol a snarling black panther, which earned the LCFO the nickname the Black Panther Party. The symbol inspired African Americans across the country, including the founders of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, who named their organization after the LCFO symbol. A team of SNCC field secretaries, led by Stokely Carmichael, helped Lowndes County activists build the LCFO. The SNCC workers also drew upon this experience to develop the theories and programs behind Black Power, which Carmichael introduced to the nation during the summer of 1966.

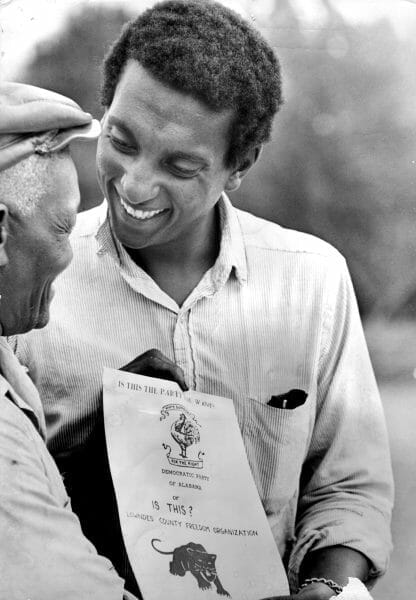

Stokely Carmichael

In the 1966 general election, the LCFO ran a full slate of African Americans for local office. The Black Panther candidates were defeated by their white opponents, largely as a result of ballot fraud. Nevertheless, the LCFO laid the foundation for the eventual rise of African American political power in the county and across the Black Belt. The LCFO also inspired the creation of the National Democratic Party of Alabama (NDPA), a statewide alternative to the Alabama Democratic Party. The LCFO merged with the NDPA in 1970, the same year that Lowndes County activist John Hulett became the county’s first black sheriff.

Stokely Carmichael

In the 1966 general election, the LCFO ran a full slate of African Americans for local office. The Black Panther candidates were defeated by their white opponents, largely as a result of ballot fraud. Nevertheless, the LCFO laid the foundation for the eventual rise of African American political power in the county and across the Black Belt. The LCFO also inspired the creation of the National Democratic Party of Alabama (NDPA), a statewide alternative to the Alabama Democratic Party. The LCFO merged with the NDPA in 1970, the same year that Lowndes County activist John Hulett became the county’s first black sheriff.

The embrace of independent politics by African Americans signaled the transition from civil rights to Black Power. During the Black Power era, African Americans organized more explicitly around racial solidarity and black consciousness. They also placed a greater emphasis on economic and political empowerment. The emergence of Black Power did not mark the end of black protest, but rather the start of a new, more radical phase. In cities across the state, Black Power looked very much like it did elsewhere in the country, both in terms of programs and organization. In rural areas, particularly in the Black Belt, it assumed a slightly different form and function. Black farmers, for example, pursued economic empowerment through agricultural co-operatives, such as the Southwest Alabama Farmers Cooperative Association (SWAFCA).

The civil rights movement transformed Alabama and the rest of the nation, ending a century of legal segregation and creating new opportunities for African Americans and others. Although it did not solve every problem caused by racial discrimination, it helped to forge a more open and democratic Alabama and United States of America.

Further Reading

- Anker, Daniel, and Barak Goodman, directors. Scottsboro: An American Tragedy. Boston: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2001. 1 hr., 14 mins.

- Ashmore, Susan Youngblood. Carry It On: The War on Poverty and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama, 1964-1972. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008.

- Bagwell, Orlando, and W. Noland Walker, directors. Citizen King. The American Experience Series. WGBH Educational Foundation and ROJA Productions, Inc., 2004. 2 hrs. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/mlk/#film_description

- Bagwell, Orlando, et al, directors. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Movement. Blackside Productions, 1987-90. 14 episodes. https://www.pbs.org/show/eyes-on-the-prize/

- Burns, Stewart, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- DuVernay, Ava, director. Selma. Pathé/Harpo Films/Plan B Entertainment, 2014. 2 hrs., 8 min.

- Eagles, Charles W. Outside Agitator: Jon Daniels and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Eskew, Glenn T. But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Gaillard, Frye. Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement that Changed America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Gandbhir, Geeta, and Sam Pollard, directors. Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power. Multitude Films, 2022. 1 hr., 30 mins.

- Garrow, David J. Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1978.

- Houston, Robert, director. Mighty Times: The Legacy of Rosa Parks. HBO Films/Southern Poverty Law Center, 2002. 40 mins.

- Jeffries, Hasan K. Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt. New York: NYU Press, 2009.

- Johnson, Clark, director. Boycott. HBO Films, 2001. 1 hr., 58 mins.

- Lee, Spike, director. Four Little Girls. HBO Films, 1997. 1 hr., 42 mins.

- Mannis, Andrew. A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- McWhorter, Diane. Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

- Norrell, Robert J. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee. New York: Vintage Books, 1985.

- Thornton, J. Mills. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

External Links

- Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

- National Parks Service: Civil Rights in America

- The Library of Congress: "African American Odyssey: The Civil Rights Era"

- Rosa Parks Museum

- New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Civil Rights Digital Library

- The Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists

- U.S. Civil Rights Trail