Joseph Glover Baldwin

Lawyer, author, and politician Joseph Glover Baldwin (1815-1864) was a popular humor writer in the years before the Civil War. He primarily wrote on the topic of the Old Southwest, as the southern frontier at the time has come to be known by historians. He is best known for his work The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi, a series of humorous sketches describing life on the frontier. Flush Times established Baldwin as both a serious author and astute observer of antebellum Alabama.

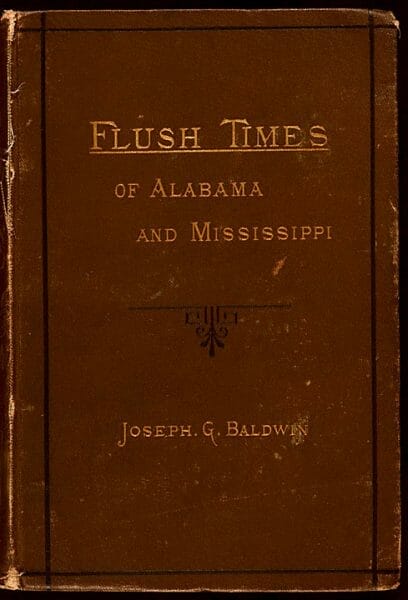

Flush Times Cover

Baldwin was born on January 21, 1815, in Friendly Grove Factory, Virginia, to Joseph Clarke and Eliza Cooke Baldwin. One of seven children, Baldwin lived in several parts of Virginia, including Winchester and Staunton, where he obtained some formal education and studied law under his uncle. A lawyer at age 20, Baldwin relocated to Lexington and later to Buchanan, where he worked as a newspaper editor. In 1836, Baldwin set out for Mississippi to earn his fortune on what was then the southwestern frontier, but by 1837 he had settled in Gainesville, Sumter County, Alabama, where he opened a law practice. In 1840, Baldwin married Sidney White, daughter of a Talladega judge, with whom he would have seven children. Baldwin became involved in politics during the 1840 presidential race and won election to the Alabama state legislature as a Whig in 1843. After serving one term, he returned to his legal practice and actively supported the Whig Party. Baldwin ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Congress in 1849 and then moved to Livingston in Sumter County, where he opened another legal partnership. He also turned to writing, publishing The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi, a work of Old Southwest humor in 1853, and Party Leaders, a political history of the United States, in 1854. Baldwin moved to California during the summer of 1854, seeking economic opportunity as a lawyer in San Francisco. In 1858, having become a Democrat after the demise of the Whig Party, Baldwin was elected to the California Supreme Court, where he served until 1862. Baldwin continued to write, but his “Flush Times of California” lay unfinished upon his death from tetanus on September 30, 1864.

Flush Times Cover

Baldwin was born on January 21, 1815, in Friendly Grove Factory, Virginia, to Joseph Clarke and Eliza Cooke Baldwin. One of seven children, Baldwin lived in several parts of Virginia, including Winchester and Staunton, where he obtained some formal education and studied law under his uncle. A lawyer at age 20, Baldwin relocated to Lexington and later to Buchanan, where he worked as a newspaper editor. In 1836, Baldwin set out for Mississippi to earn his fortune on what was then the southwestern frontier, but by 1837 he had settled in Gainesville, Sumter County, Alabama, where he opened a law practice. In 1840, Baldwin married Sidney White, daughter of a Talladega judge, with whom he would have seven children. Baldwin became involved in politics during the 1840 presidential race and won election to the Alabama state legislature as a Whig in 1843. After serving one term, he returned to his legal practice and actively supported the Whig Party. Baldwin ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Congress in 1849 and then moved to Livingston in Sumter County, where he opened another legal partnership. He also turned to writing, publishing The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi, a work of Old Southwest humor in 1853, and Party Leaders, a political history of the United States, in 1854. Baldwin moved to California during the summer of 1854, seeking economic opportunity as a lawyer in San Francisco. In 1858, having become a Democrat after the demise of the Whig Party, Baldwin was elected to the California Supreme Court, where he served until 1862. Baldwin continued to write, but his “Flush Times of California” lay unfinished upon his death from tetanus on September 30, 1864.

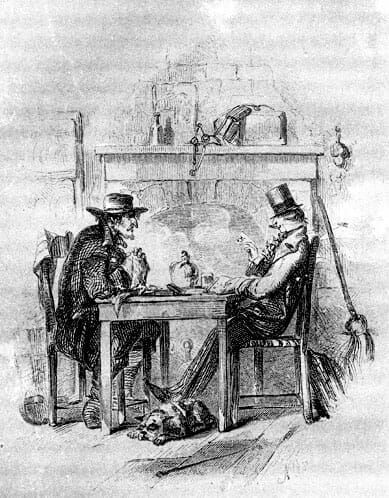

Simon Suggs Jr.

In Flush Times, Baldwin portrays the Old Southwest frontier as a chaotic place where the traditional social order, with its hierarchies, castes, and long-established conventions, had not yet taken hold. The freedom of the frontier allowed individuals who would have been trapped in the lower ranks of society in established communities to rise to prominence. But the weak social, political, and judicial institutions in the Old Southwest, particularly the courts, allowed individuals to exploit one another with little fear of judicial repercussions. In a nod to his profession, Baldwin stressed in Flush Times that lawyers brought order to the individualistic society of frontier Alabama and Mississippi. He highlights this theme both through the style of the book and in the nature of the sketches.

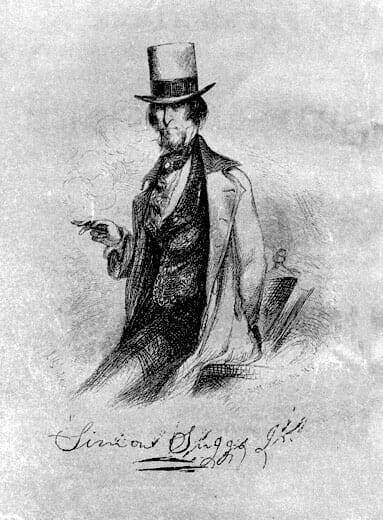

Simon Suggs Jr.

In Flush Times, Baldwin portrays the Old Southwest frontier as a chaotic place where the traditional social order, with its hierarchies, castes, and long-established conventions, had not yet taken hold. The freedom of the frontier allowed individuals who would have been trapped in the lower ranks of society in established communities to rise to prominence. But the weak social, political, and judicial institutions in the Old Southwest, particularly the courts, allowed individuals to exploit one another with little fear of judicial repercussions. In a nod to his profession, Baldwin stressed in Flush Times that lawyers brought order to the individualistic society of frontier Alabama and Mississippi. He highlights this theme both through the style of the book and in the nature of the sketches.

Baldwin employs a formal tone to distance the reader from the rawness of frontier society. He describes the faults of others and the unsettled nature of the frontier rather than allowing the reader to encounter this world directly. In the first sketch, “Ovid Bolus, Esq.,” Baldwin describes a notorious liar who swindled, tricked, and stole his way to prominence in the Old Southwest. Eventually, as the rule of law is strengthened, Bolus drifts further west, seeking a new frontier to exploit. In the sketch, Baldwin humorously describes Bolus’s character, but the reader does not encounter Bolus’s own words or perspective. Other Old Southwest humorists, such as George Washington Harris, made extensive use of the vernacular speech of the common folk, but except for the sketch “Simon Suggs, Jr., Esq.; A Legal Biography,” Baldwin uses little vernacular. He again separates the reader from the vulgarities of his subjects. As literary critics Kenneth Lynn and Mary Ann Wimsatt have pointed out, Baldwin’s polished prose, which includes numerous literary allusions and frequent Latin and French phrases, moves the reader to a “safe” space where the Southwest can be observed through Baldwin’s educated and self-assured point of view. In doing so, Baldwin creates literary order out of frontier chaos.

As scholar Merritt Moseley has noted, Baldwin employs different styles of sketches both to educate and to entertain the reader. Many of the sketches in the book are short, interpretative essays of various frontier lawyers, some actual persons, others fictional. The often satirical stories focus more on the character of the subject than mundane personal details, and Baldwin uses them to demonstrate the need for men of good character in a free society. For example, in “Cave Burton, Esq.” Baldwin relates how a group of lawyers trick their colleague Cave Burton by playing on his gluttony and pride. In “Hon. S. S. Prentiss,” Baldwin discusses the life of the real-life Mississippi lawyer and highlights how he brought order to the frontier through his self-control, rational approach to the law, and his force of will. Interspersed throughout the book are shorter, humorous sketches, such as “Sharp Financiering” and “Squire A. and the Fritters,” that provide comic relief, usually in the form of stories in which someone outwits another person either for amusement or financial gain.

Turning the Jack

In his longer pieces of social commentary, Baldwin expresses Whig theories of individualism, freedom, and social order. In “How the Times Served the Virginians” and “The Bar of the South-West,” Baldwin discusses the differences between the established communities of the eastern seaboard and the emerging societies of the frontier. Although Baldwin decries the abuse of freedom, he maintains that the open society on the southwestern frontier provides opportunity for men to pursue greatness in their quest to organize society through law and good republican government. He recalls with some nostalgia, for example, the venerable customs of Virginia but does not wish for the old Virginia society to be replicated on the frontier. He prefers an open society in which individuals may pursue their own goals under the protection of the law. Baldwin accepts slavery as a natural part of the Southwest, however, and does not apply his love of liberty to African Americans.

Turning the Jack

In his longer pieces of social commentary, Baldwin expresses Whig theories of individualism, freedom, and social order. In “How the Times Served the Virginians” and “The Bar of the South-West,” Baldwin discusses the differences between the established communities of the eastern seaboard and the emerging societies of the frontier. Although Baldwin decries the abuse of freedom, he maintains that the open society on the southwestern frontier provides opportunity for men to pursue greatness in their quest to organize society through law and good republican government. He recalls with some nostalgia, for example, the venerable customs of Virginia but does not wish for the old Virginia society to be replicated on the frontier. He prefers an open society in which individuals may pursue their own goals under the protection of the law. Baldwin accepts slavery as a natural part of the Southwest, however, and does not apply his love of liberty to African Americans.

Flush Times, while not intended to be a dispassionate historical account, is an important commentary on antebellum Alabama culture. Using humor, Baldwin persuades his readers, both southerners and northerners, that law and lawyers played indispensable parts in transforming the American frontier into an orderly, free society. Despite its national audience and message, Flush Times reveals most about the challenges antebellum white southerners faced in building stable societies on the southwestern frontier. Baldwin’s attention to place—to antebellum Alabama and Mississippi—makes Flush Times a significant work of nineteenth-century southern literature. In 2018, Baldwin was inducted into the Alabama Writers Hall of Fame.

Further Reading

- Beidler, Philip D. First Books: The Printed Word and Cultural Formation in Early Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Justus, James H. Introduction to The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi, by Joseph Glover Baldwin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

- Moseley, Merritt W., Jr. “Joseph Glover Baldwin, 1815-1864.” In Fifty Southern Writers Before 1900, edited by Robert Bain and Joseph M. Flora, pp. 29-37. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

- Watson, Charles S. “Order out of Chaos: Joseph Glover Baldwin’s The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi.” Alabama Review 45 (October 1992): 257-272.

- Wimsatt, Mary Ann. “Bench and Bar: Baldwin’s Lawyerly Humor.” In The Humor of the Old South, edited by M. Thomas Inge and Edward J. Piacentino, pp. 187-98. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2001.