David Bibb Graves (1927-31, 1935-39)

Bibb Graves

David Bibb Graves (1873-1942) was one of Alabama’s most important governors, serving during critical periods of Alabama history, the first during the twilight of prosperity and the first years of the Great Depression, and the second during tumultuous political conflict and slow recovery. During his two terms from 1927-1931 and 1935-1939, his administrations expanded the role of state government and intensified the political factionalism between liberals and conservatives within the state. He was a cousin of Alabama‘s first and second governors, William Wyatt and Thomas Bibb.

Bibb Graves

David Bibb Graves (1873-1942) was one of Alabama’s most important governors, serving during critical periods of Alabama history, the first during the twilight of prosperity and the first years of the Great Depression, and the second during tumultuous political conflict and slow recovery. During his two terms from 1927-1931 and 1935-1939, his administrations expanded the role of state government and intensified the political factionalism between liberals and conservatives within the state. He was a cousin of Alabama‘s first and second governors, William Wyatt and Thomas Bibb.

Born on April 1, 1873, at Hope Hull, in Montgomery County, to David and Mattie Graves (descendants of Welsh immigrants who settled in colonial America), the future governor grew up in Texas. He attended public schools in that state before returning to Alabama to attend the University of Alabama, where he served as captain of the Alabama Corps of Cadets and earned membership in Phi Beta Kappa. Graves graduated in 1893 and then briefly studied law at the University of Texas before transferring to Yale University’s law school, where he completed an LL.B. degree in 1896. The following March, Graves began his life-long residence in Montgomery, where he established a law practice.

In 1898, Graves began the first of two terms as a member of the Alabama House of Representatives (1898-99, 1900-01). He married first cousin Dixie Bibb in 1900, during his second term. During these years, he allied with progressives such as governors Joseph F. Johnson and Braxton Bragg Comer and opposed ratification of the racist 1901 Constitution. In 1904, he was defeated in a race against the incumbent Democratic congressman from the Second Congressional District. Although he did not run for office again for nearly a decade, he remained politically active, managing Comer’s 1904 campaign in Montgomery County and serving as chair of the State Democratic Executive Committee in 1914, during which time he helped write a new election law replacing runoff elections with a first- and second-choice option ballot system.

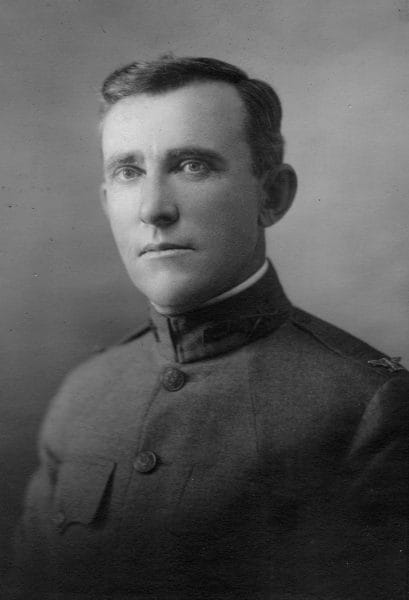

Bibb Graves

He continued his military interests, serving as adjutant general of the Alabama National Guard from 1907 until 1911. He helped organize the First Alabama Cavalry Regiment, serving successively as lieutenant colonel and colonel. The regiment was mustered into federal service in September 1916 and ordered to the Mexican border during a period of cross-border raids by Mexican revolutionaries. After the unit’s return to Alabama, Graves’s regiment became part of the Fifty-first Artillery Brigade, with Graves serving as a colonel in the 117th Field Artillery. Shipped to France during World War I, his unit engaged in heavy fighting as part of the Thirty-first Division. After the war, he organized the politically potent Alabama department of the American Legion, for which he also served as chair.

Bibb Graves

He continued his military interests, serving as adjutant general of the Alabama National Guard from 1907 until 1911. He helped organize the First Alabama Cavalry Regiment, serving successively as lieutenant colonel and colonel. The regiment was mustered into federal service in September 1916 and ordered to the Mexican border during a period of cross-border raids by Mexican revolutionaries. After the unit’s return to Alabama, Graves’s regiment became part of the Fifty-first Artillery Brigade, with Graves serving as a colonel in the 117th Field Artillery. Shipped to France during World War I, his unit engaged in heavy fighting as part of the Thirty-first Division. After the war, he organized the politically potent Alabama department of the American Legion, for which he also served as chair.

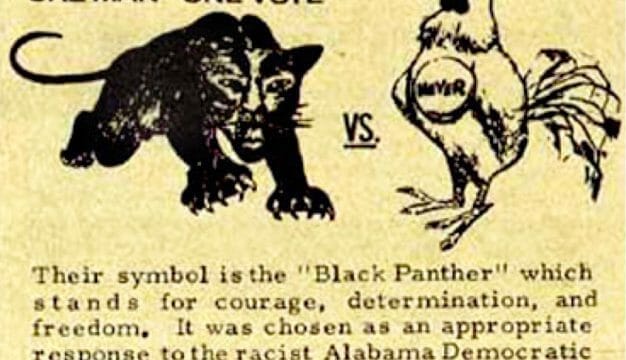

Like many state militia officers after the war, Graves effectively used his military associations with veterans to further his political career. Graves ran in the 1922 governor’s race but lost badly to conservative William W. Brandon. Although most pundits wrote him off as a two-time loser, Graves fashioned one of the strongest coalitions in Alabama political history in his successful 1926 gubernatorial race. Prohibitionists and women backed him because of his stand on temperance and women’s rights. Organized labor approved his record on issues affecting working people and his pledge to abolish the convict-lease system, which depressed the wages of free labor. Educators endorsed his pledge to establish a minimum seven-month school term statewide (44 counties had terms shorter than that in 1926) and to increase education funding. He also used his position as Grand Cyclops of the Montgomery Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan to win much of that powerful voting bloc in 1926. Although Graves won less than 30 percent of first-choice votes against lieutenant governor Charles S. McDowell of Eufaula (who was backed by conservative Black Belt planters and powerful Birmingham corporate interests), he did well enough with second-choice votes to win the Democratic nomination. He ran strongest among rural white voters in north Alabama and weakest in the Black Belt.

Young Dixie Bibb

As Alabama’s 40th governor, Graves compiled an impressive record. The legislature enacted his proposal to end the convict-lease system late in 1927, making Alabama the last state in the nation to do so. His aggressive highway construction efforts absorbed many of the convicts in state road work. He financed a $30 million road and toll bridge program by imposing higher state fees on driver’s licenses and gasoline. By 1930, the state’s hard-surfaced roads had increased from 5,000 miles when he took office to more than 20,000 miles. The number of registered vehicles in the state had climbed from 74,637 in 1920 to 277,147 in 1930. He also convinced the legislature to pass the largest educational appropriation in state history to that time, increasing Governor Brandon’s $9.9 million education budget to $25 million. Graves also presided over a complete revision of the state’s education code, adding a Division of Negro Education with a black director. He also supported legislation for a new 225-bed hospital for blacks at Mount Vernon and a 200-bed addition to Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, as well as major improvements for the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind at Talladega. State appropriations for child welfare and public health doubled, exceeding the national average.

Young Dixie Bibb

As Alabama’s 40th governor, Graves compiled an impressive record. The legislature enacted his proposal to end the convict-lease system late in 1927, making Alabama the last state in the nation to do so. His aggressive highway construction efforts absorbed many of the convicts in state road work. He financed a $30 million road and toll bridge program by imposing higher state fees on driver’s licenses and gasoline. By 1930, the state’s hard-surfaced roads had increased from 5,000 miles when he took office to more than 20,000 miles. The number of registered vehicles in the state had climbed from 74,637 in 1920 to 277,147 in 1930. He also convinced the legislature to pass the largest educational appropriation in state history to that time, increasing Governor Brandon’s $9.9 million education budget to $25 million. Graves also presided over a complete revision of the state’s education code, adding a Division of Negro Education with a black director. He also supported legislation for a new 225-bed hospital for blacks at Mount Vernon and a 200-bed addition to Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, as well as major improvements for the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind at Talladega. State appropriations for child welfare and public health doubled, exceeding the national average.

A booming state economy funded these improvements. But the 1929 stock market crash and ensuing depression devastated the state’s manufacturing economy and punished the state for acquiring so much bonded indebtedness. Graves’s “spend now, pay later” philosophy for funding infrastructure improvements made him vulnerable to conservative criticism, as did his habit of appointing political cronies to office and his early fraternization with the KKK, despite his late-1920s denunciation of the organization’s violence and his resignation from its membership.

Unable to stand for reelection under terms of the state constitution, Graves returned to his law practice until 1934, when voters easily reelected him over conservative Birmingham corporate lawyer Frank M. Dixon. He thus became the first governor since enactment of the 1901 Constitution to win a second term. During his 1934 race, Graves called his opponents “Big Mules,” using the image of a hearty animal tied to the end of a heavily loaded wagon, munching corn contentedly, while a scrawny mule harnessed to the front of the wagon pulled the entire load. The term and the imagery would remain a short-hand description of Alabama political factionalism and economic class divisions into the twenty-first century.

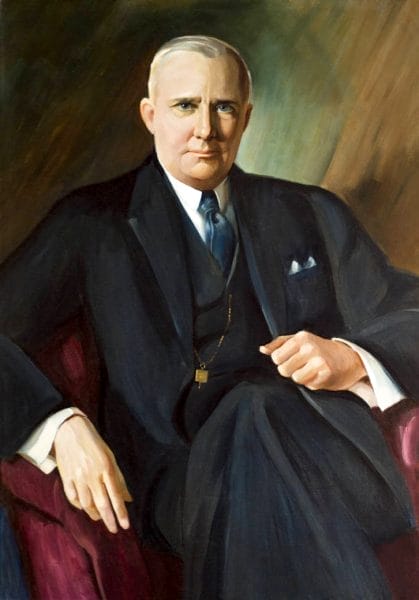

David Bibb and Dixie Bibb Graves

During his second term, Graves sided with increasingly powerful labor unions, created a new state Department of Labor, appointed many women as administrators in the department, and refused to use the state militia to break strikes. On racial matters, Graves adhered to the orthodox conservatism of his constituents. In the early 1930, nine black men were convicted of raping two white women near Scottsboro, Jackson County. Evidence against the men was flimsy, and the star witness later admitted that she and her friend had lied to avoid prosecution for vagrancy. The trials drew worldwide protests, and a courageous Alabama judge granted new trials for some of the men on the basis that the evidence could not sustain a guilty verdict. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately overturned convictions of some defendants. Graves was repeatedly implored to grant the men a pardon or parole, but even in the face of a private appeal from Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, he refused to alleviate this injustice. On matters other than race, however, he was a loyal New Dealer, supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt and the president’s Alabama allies. In education, he created the Minimum Foundation Program to equalize educational opportunity for all students, regardless of where they lived, provided free textbooks for some grades, and reluctantly passed the first state sales tax to fund schools when property tax increases failed. The governor also appointed his wife, Dixie (an enthusiastic supporter of women’s rights), to fill Hugo Black‘s unexpired U.S. Senate seat in 1937, after Black was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

David Bibb and Dixie Bibb Graves

During his second term, Graves sided with increasingly powerful labor unions, created a new state Department of Labor, appointed many women as administrators in the department, and refused to use the state militia to break strikes. On racial matters, Graves adhered to the orthodox conservatism of his constituents. In the early 1930, nine black men were convicted of raping two white women near Scottsboro, Jackson County. Evidence against the men was flimsy, and the star witness later admitted that she and her friend had lied to avoid prosecution for vagrancy. The trials drew worldwide protests, and a courageous Alabama judge granted new trials for some of the men on the basis that the evidence could not sustain a guilty verdict. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately overturned convictions of some defendants. Graves was repeatedly implored to grant the men a pardon or parole, but even in the face of a private appeal from Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, he refused to alleviate this injustice. On matters other than race, however, he was a loyal New Dealer, supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt and the president’s Alabama allies. In education, he created the Minimum Foundation Program to equalize educational opportunity for all students, regardless of where they lived, provided free textbooks for some grades, and reluctantly passed the first state sales tax to fund schools when property tax increases failed. The governor also appointed his wife, Dixie (an enthusiastic supporter of women’s rights), to fill Hugo Black‘s unexpired U.S. Senate seat in 1937, after Black was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

After another hiatus from politics, Graves was once again the overwhelming favorite to win the 1942 governor’s race for an unprecedented third term when he died of kidney failure in mid-March. Graves’ legacy was a paradox. As the best-educated governor in Alabama’s history, he was closely allied to the KKK and practiced patronage politics. Fiercely opposed by the state’s Big Mules, his personal background was more similar to theirs than to the working-class blacks and whites whose interests he championed. His unparalleled promotion of women to government positions, his education reforms, support of better roads, organized labor, and public health, endeared him to millions of ordinary Alabamians of both races but generated bitter hatred among conservative interests. Certainly Graves, along with James E. “Big Jim” Folsom, were Alabama’s most liberal twentieth century governors.

Further Reading

- Flynt, Wayne. “Bibb Graves.” Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret E. Armbrester. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

- Gilbert, William E. “The First Administration of Governor Bibb Graves, 1927-1930.” M.A. thesis, University of Alabama, 1953.