Green Corn Ceremony

Green Corn Ceremony

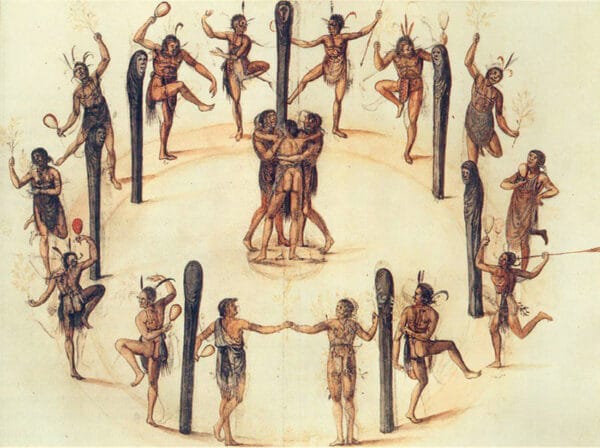

The Green Corn Ceremony, also known as the busk (from the Creek word poskita, “to fast”), was the most important of the many annual traditional ceremonies performed by Indian tribes of the Southeast. It is likely that most Indian groups in the region practiced a version of this celebration, which was held in mid-summer when the early corn became ripe. The annual renewal ceremony generally lasted either four or eight days, and fasting represented only one of the rituals involved. Feasting and acts of social and material renewal also played an important role. In fact, as anthropologist Charles Hudson has pointed out, modern Americans would have to combine Thanksgiving, New Year’s Day, Yom Kippur, Lent, and Mardi Gras to have a holiday that approached the breadth and importance of the Green Corn Ceremony.

Green Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony, also known as the busk (from the Creek word poskita, “to fast”), was the most important of the many annual traditional ceremonies performed by Indian tribes of the Southeast. It is likely that most Indian groups in the region practiced a version of this celebration, which was held in mid-summer when the early corn became ripe. The annual renewal ceremony generally lasted either four or eight days, and fasting represented only one of the rituals involved. Feasting and acts of social and material renewal also played an important role. In fact, as anthropologist Charles Hudson has pointed out, modern Americans would have to combine Thanksgiving, New Year’s Day, Yom Kippur, Lent, and Mardi Gras to have a holiday that approached the breadth and importance of the Green Corn Ceremony.

Most of the detailed descriptions we have of the ceremony come from Oklahoma and were recorded during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, decades after Indian removal. A few versions of the ceremony date back to pre-removal times, including trader James Adair‘s detailed description of a southeastern Indian celebration from the mid-eighteenth century, and playwright John Howard Payne’s 1835 report of the last busk held by the Creek Indians in Alabama prior to removal. Naturalist William Bartram and federal Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins also produced accounts of the ceremony as it was practiced in the Southeast. Although all the accounts differ in terms of minor details and in the timing of events, they all follow the same general pattern. The Green Corn Ceremony took place when the first corn ripened. On the first day of the ceremony, everyone gathered in the town square of the host village for the opening rituals of the ceremony, which began with a big feast, a necessary preparation for the fast that would follow. None of the dishes, however, included any of the newly ripened corn.

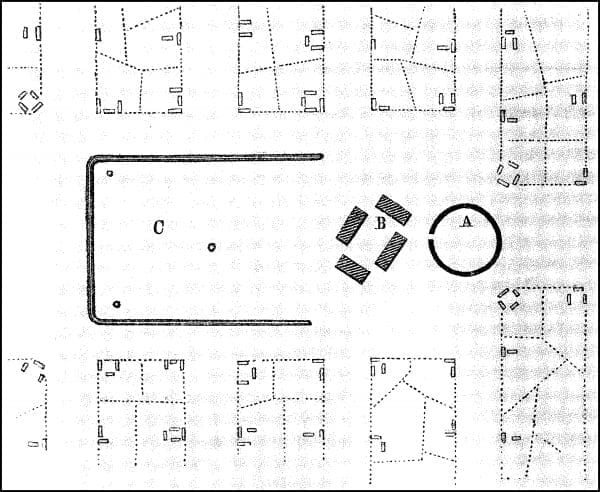

Engraving of Creek Town Layout

The fasting period generally lasted between one-and-a-half and two days. The men practiced a strict fast, but women, children, and the elderly were often allowed to eat certain foods during prescribed times. During this time, in keeping with the theme of renewal, men worked together to repair and refurbish public buildings in the town and women worked on the private dwellings. In the eighteenth century, people destroyed or disposed of their belongings, but later, they repaired or cleaned utensils, tools, and clothes. The focal point of the ceremony was the town center, where most important public events took place. The square dirt plaza was bordered by four shed-roofed structures, open on three sides, that contained bench-seating. Villagers kept the plaza meticulously swept during the entire Green Corn Ceremony and strictly upheld the sanctity of the area—children were not allowed to wander into the square and dogs that did were often killed. The area served as the performance space for many critical elements of the ceremony, including dances by both women and men (some of which lasted all night) and speeches made by respected elders who beseeched everyone to forgive the past year’s transgressions and adhere to societal mores in the future.

Engraving of Creek Town Layout

The fasting period generally lasted between one-and-a-half and two days. The men practiced a strict fast, but women, children, and the elderly were often allowed to eat certain foods during prescribed times. During this time, in keeping with the theme of renewal, men worked together to repair and refurbish public buildings in the town and women worked on the private dwellings. In the eighteenth century, people destroyed or disposed of their belongings, but later, they repaired or cleaned utensils, tools, and clothes. The focal point of the ceremony was the town center, where most important public events took place. The square dirt plaza was bordered by four shed-roofed structures, open on three sides, that contained bench-seating. Villagers kept the plaza meticulously swept during the entire Green Corn Ceremony and strictly upheld the sanctity of the area—children were not allowed to wander into the square and dogs that did were often killed. The area served as the performance space for many critical elements of the ceremony, including dances by both women and men (some of which lasted all night) and speeches made by respected elders who beseeched everyone to forgive the past year’s transgressions and adhere to societal mores in the future.

During the ceremonies, male participants took sacred drinks, or “medicine.” Little information has survived about this practice, but scholars do know that the men ingested a variety of plant-based mixtures during the course of the busk. The plants’ leaves were used to make a caffeinated beverage, similar to tea, that the men drank as part of a ritual purification rite, which sometimes included vomiting of the drink to symbolize that purification. The color white symbolized an uncontaminated state for southeastern Indians, and they referred to the concoction as the white drink. The liquid is actually black like coffee, however, and it became known as the black drink among Europeans.

Choctaw Stickball Player

The preoccupation with ritual and purity extended beyond the individual. Indeed, it can be argued that the most important event of the Green Corn Ceremony was the rekindling of the sacred fire in the town square and the rest of the town. Southeastern Indians viewed the fire, which they maintained continually, as an earthly representation of the sun. They also believed that during the course of a year the sacred fire slowly became polluted as community members violated societal rules and principles, and therefore it had to be renewed. In preparation for this event, villagers extinguished all the fires in the town, symbolically extinguishing the year’s transgressions, and then they cleaned all the hearths. People reestablished their social relationships, and the societies at large forgave all crimes except murder. After the world had figuratively and literally been made new with the relighting of the sacred fire, the villagers enjoyed a huge feast centered on the first corn. The meal was followed by more dancing and games to celebrate the fresh beginning. The new sacred fire was then used to relight the townspeople’s own fires.

Choctaw Stickball Player

The preoccupation with ritual and purity extended beyond the individual. Indeed, it can be argued that the most important event of the Green Corn Ceremony was the rekindling of the sacred fire in the town square and the rest of the town. Southeastern Indians viewed the fire, which they maintained continually, as an earthly representation of the sun. They also believed that during the course of a year the sacred fire slowly became polluted as community members violated societal rules and principles, and therefore it had to be renewed. In preparation for this event, villagers extinguished all the fires in the town, symbolically extinguishing the year’s transgressions, and then they cleaned all the hearths. People reestablished their social relationships, and the societies at large forgave all crimes except murder. After the world had figuratively and literally been made new with the relighting of the sacred fire, the villagers enjoyed a huge feast centered on the first corn. The meal was followed by more dancing and games to celebrate the fresh beginning. The new sacred fire was then used to relight the townspeople’s own fires.

The ceremony remained important for southeastern Indians in the post-Removal period. As people abandoned town life for more dispersed settlements and town governments lost much of their authority, the town square lost its importance for political affairs but retained ceremonial significance as “stomp grounds” or dance grounds for important ceremonial occasions, particularly the Green Corn Dance. Today, many Creek and Yuchi towns in Oklahoma maintain their stomp grounds and continue to celebrate the ceremony, and there is a resurgence of interest in this ceremonial practice among other tribes as well.

Additional Resources

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. Kathryn E. Holland Braund, ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Hudson, Charles. The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976.