Albert P. Brewer (1968-71)

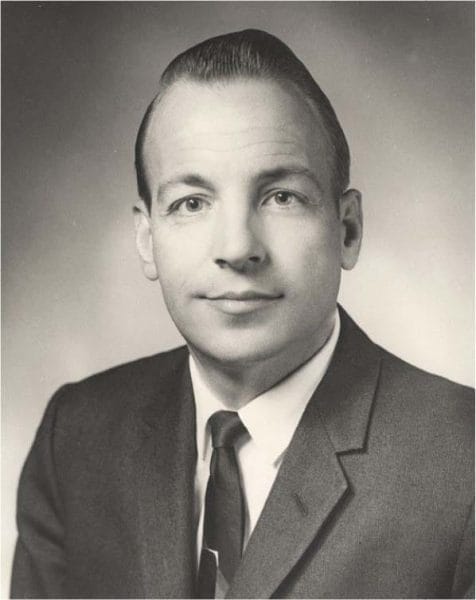

Albert P. Brewer

In May 1968, Lt. Gov. Albert Brewer (1928-2016) assumed the governorship when Gov. Lurleen Wallace died from cancer. In his 33 months as chief executive, Brewer established by executive order Alabama‘s first code of ethics for state employees, decreased the power of special interests in the capital, and formed a constitutional reform commission. Brewer also brought to the office a zeal for efficiency and economy in state government and a desire to make Alabama’s public education system worthy of national respect. To date, he is the only governor in Alabama history to have held the offices of speaker, lieutenant governor, and governor in succession.

Albert P. Brewer

In May 1968, Lt. Gov. Albert Brewer (1928-2016) assumed the governorship when Gov. Lurleen Wallace died from cancer. In his 33 months as chief executive, Brewer established by executive order Alabama‘s first code of ethics for state employees, decreased the power of special interests in the capital, and formed a constitutional reform commission. Brewer also brought to the office a zeal for efficiency and economy in state government and a desire to make Alabama’s public education system worthy of national respect. To date, he is the only governor in Alabama history to have held the offices of speaker, lieutenant governor, and governor in succession.

Albert Preston Brewer was born on October 26, 1928, in Bethel Springs, Tennessee, to Daniel Austin Brewer and Clara Yarber Brewer. When Albert was a child, his father relocated the family to Decatur, in Morgan County, to work for the Tennessee Valley Authority. Albert remained in Decatur until 1946, when he enrolled in the University of Alabama, where he majored in both history and political science and worked at a local drugstore. In 1952, Brewer graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law, where he formed close friendships with other students who would become major figures in Alabama’s history during the second half of the twentieth century. These friendships proved invaluable to Brewer during his years in government.

Brewer returned to Decatur and established a law practice. In 1954, Morgan County’s state representative retired, and Brewer was prodded by local business and community leaders to run for the vacant seat. He was initially reluctant to run. Brewer had recently married Martha Farmer, with whom he would have two girls, and wanted to focus on his practice. The potential for new clients, visibility, and a desire to pursue his interest in public service, however, convinced him to seek public office.

Brewer won and entered the legislature in 1955, where he joined many of his old law school friends. This core of young, professional, enthusiastic legislators held progressive ideas, such as improving education, reapportioning the state legislature, modernizing rules for the legal profession, improving the highway system, and focusing on economic development. Brewer was reelected in 1958 and 1962 to second and third terms, and in 1963 he defeated better-known candidates to become one of the youngest speakers of the state house in Alabama history. He enjoyed Gov. George Wallace‘s approval, and his congenial and urbane demeanor made him popular with other legislators.

Although considered a “Wallace man,” Brewer was able to remain relatively independent of the governor. In 1966, with Wallace unable to succeed himself, Brewer considered a run for chief executive but gave up that idea when Lurleen Wallace entered the race with the backing of husband George. Brewer held no illusions that he could win if she ran. He decided, therefore, to run for lieutenant governor, and with support from Wallace allies, organized labor, and urban areas, he defeated his opponent by a vote of more than four to one. As lieutenant governor, Brewer supported Lurleen Wallace, but on his own he initiated an educational review commission that later provided the framework for his educational reform package as governor. During early 1968, Brewer and other Alabama attorneys traveled to northern states to help place former governor George Wallace on state ballots as an independent candidate for president.

Albert Brewer Oath of Office

At Lurleen Wallace’s death on May 7, 1968, Brewer became the first lieutenant governor to take the office of governor under the 1901 constitution. He replaced only a few of Wallace’s aides with his own. One of the first differences that Alabamians noticed about Gov. Brewer was how his style and disposition differed from George Wallace. Whereas Wallace tended to lean towards demagoguery, the Anniston Star described Brewer as a man with a “neat, open, ‘nice guy’ appearance,” who used light wit and irony to get his message across. Nonetheless, many Alabamians continued to perceive Brewer as a “Wallace man” and wondered whether he could become his own person. Three of Brewer’s initial actions as governor moved him away from Wallace’s style of governing. He established a state motor pool and cut in half the use of personal state vehicles, saving the state more than $500,000 a year. He centralized departmental computers into one unified system, which saved the state another $1 million annually. Finally, Brewer left vacant many of the jobs in the governor’s cabinet that had long been awarded to political operatives.

Albert Brewer Oath of Office

At Lurleen Wallace’s death on May 7, 1968, Brewer became the first lieutenant governor to take the office of governor under the 1901 constitution. He replaced only a few of Wallace’s aides with his own. One of the first differences that Alabamians noticed about Gov. Brewer was how his style and disposition differed from George Wallace. Whereas Wallace tended to lean towards demagoguery, the Anniston Star described Brewer as a man with a “neat, open, ‘nice guy’ appearance,” who used light wit and irony to get his message across. Nonetheless, many Alabamians continued to perceive Brewer as a “Wallace man” and wondered whether he could become his own person. Three of Brewer’s initial actions as governor moved him away from Wallace’s style of governing. He established a state motor pool and cut in half the use of personal state vehicles, saving the state more than $500,000 a year. He centralized departmental computers into one unified system, which saved the state another $1 million annually. Finally, Brewer left vacant many of the jobs in the governor’s cabinet that had long been awarded to political operatives.

Brewer’s greatest contribution, however, was in the area of education. In 1969, he moved through the legislature one of the most successful education reform packages ever passed in Alabama. The previous year, Alabama had funded education at $200 less per child than the national average and $81 less than the southeast average, with only Mississippi providing less. Teachers’ salaries in Alabama ranked 46th in the nation. Brewer called a special session of the legislature and held pre-session meetings with small groups of legislators to work out details of the package and to flatter them with his personal attention. As a testament to his hands-on style and governing skills, his reform package passed, establishing the Alabama Commission for Higher Education and giving the Alabama Education Study Commission permanent status. State support for school districts was made more equitable, education appropriations were increased more than $100 million during the next two years, and teachers received a pay increase of 12.9 percent with a conditional appropriation for another 8.2-percent raise to be implemented a year later. He also expanded the University of Alabama system to include independent campuses in Birmingham and Huntsville, in recognition of the cities’ importance to the state’s economy. In a brief tenure of many successes, this was Brewer’s finest moment.

Announcement of University of Alabama Expansion

Brewer believed that federal court-ordered integration was causing white flight from public schools and that growth in private education was eroding public support for the taxes supporting Alabama’s public schools. Viewed as a racial moderate, the young governor supported the right of parents to choose their children’s schools, actively resisted federal court orders, and appealed for patience and time from the courts in order to ease the state into integration. During his brief, two-plus years as governor, Brewer, with his soft-spoken, nonconfrontational manner, allowed race relations in the state to improve. More blacks held public office, and racial confrontations declined.

Announcement of University of Alabama Expansion

Brewer believed that federal court-ordered integration was causing white flight from public schools and that growth in private education was eroding public support for the taxes supporting Alabama’s public schools. Viewed as a racial moderate, the young governor supported the right of parents to choose their children’s schools, actively resisted federal court orders, and appealed for patience and time from the courts in order to ease the state into integration. During his brief, two-plus years as governor, Brewer, with his soft-spoken, nonconfrontational manner, allowed race relations in the state to improve. More blacks held public office, and racial confrontations declined.

Despite his less-belligerent style, Brewer was a conservative in certain areas. A lifelong Baptist, he attempted to enforce Alabama’s 1907 obscenity law, which banned nudity outside of art galleries, and he ordered the closing of drive-in movies showing X-rated films. In an action popular with most conservative Alabamians, he backed the decision of Auburn University‘s president to ban Reverend William Sloane Coffin Jr. from appearing on campus because of his open advocacy of draft evasion during the Vietnam War.

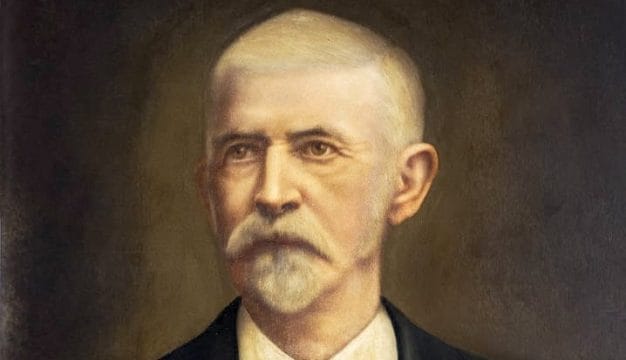

Albert Brewer Portrait

Confident of his popularity and believing that Wallace was not going to run for governor again, Brewer announced in 1969 his decision to run for a full term. Shortly before the filing deadline, Wallace declared his candidacy. In a hard-fought campaign, Brewer ran on his record as governor, asserting that the state needed a “full-time governor” and reminding voters of Wallace’s constant campaigns, which kept him out of the state. With support from a coalition that combined blacks, upper-class whites, and educated middle-class whites, Brewer shocked Wallace by running first in the Democratic primary. In the runoff campaign, the contest turned vicious. The Wallace camp whispered claims ultimately proven true of Republican support for Brewer, spread nasty and untrue rumors about Brewer’s family, and spread doctored photographs of Brewer in friendly poses with controversial black activists. Wallace supporters covered Brewer bumper stickers with their own that read, “I’m for B & B: Brewer and the Blacks.” Brewer refused to attack the Wallace administration until near the end of the runoff campaign. It was too little, too late. Preying upon fears of both race and class, Wallace defeated Brewer by 34,000 votes, dashing any hopes that Alabama might enter the “New South” era that other southern states were enjoying.

Albert Brewer Portrait

Confident of his popularity and believing that Wallace was not going to run for governor again, Brewer announced in 1969 his decision to run for a full term. Shortly before the filing deadline, Wallace declared his candidacy. In a hard-fought campaign, Brewer ran on his record as governor, asserting that the state needed a “full-time governor” and reminding voters of Wallace’s constant campaigns, which kept him out of the state. With support from a coalition that combined blacks, upper-class whites, and educated middle-class whites, Brewer shocked Wallace by running first in the Democratic primary. In the runoff campaign, the contest turned vicious. The Wallace camp whispered claims ultimately proven true of Republican support for Brewer, spread nasty and untrue rumors about Brewer’s family, and spread doctored photographs of Brewer in friendly poses with controversial black activists. Wallace supporters covered Brewer bumper stickers with their own that read, “I’m for B & B: Brewer and the Blacks.” Brewer refused to attack the Wallace administration until near the end of the runoff campaign. It was too little, too late. Preying upon fears of both race and class, Wallace defeated Brewer by 34,000 votes, dashing any hopes that Alabama might enter the “New South” era that other southern states were enjoying.

Brewer returned to his law practice and ran for governor one last time in 1978. He was confronted in that campaign with evidence that his 1970 political operatives had secretly accepted more than $400,000 in contributions from Pres. Richard Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP). Nixon, who had barely won the presidency in 1968 because of Wallace’s run as a third-party candidate, badly wanted Wallace defeated by Brewer in 1970 so that he would have no base from which to run again for president in 1972. As this connection between the Nixon and Brewer campaigns became known during the Watergate hearings and with Nixon forced from office, Brewer’s political support eroded. Despite his clear reform credentials, Alabama voters rejected Brewer and gave the Democratic nomination to nonpolitician and businessman Forrest “Fob” James Jr.

During his brief stint as governor, Brewer also focused on rewriting Alabama’s Constitution by creating the Alabama Constitutional Revision Commission, which submitted a proposal to the legislature in 1973. Brewer revisited the question of constitutional change, helping to form the group Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform in 2001 and promoting the issue across the state. A few years later, he served on another commission that presented a proposal for reform to Gov. Bob Riley. None of these efforts was successful. In the 2010s, he also headed up similar efforts, but made little headway with the legislature, though he did see the passage of four amendments to incrementally advance the goal of constitutional reform.

After ending his political career, Brewer had a long career as a professor of Law and Government at Samford University‘s Cumberland School of Law, whose faculty he joined in 1987. He enjoyed the status of respected elder statesman and was often called upon to serve on commissions that make recommendations to the governor and legislature. In 1988, he founded the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama, a think tank focused on promoting good governing practices. He retired from Samford in 2007. Brewer died on January 2, 2017.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Albert Brewer Papers. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.